Genesis P-Orridge obituary

Musician, writer and performance artist who was a co-founder of the band Throbbing Gristle

Genesis P-Orridge in New York, 2007. Photograph: Neville Elder/Redferns

Adam Sweeting

Published on Sun 15 Mar 2020

“I am at war with the status quo of society and I am at war with those in control and power,” said Genesis P-Orridge in 1989. “I’m at war with hypocrisy and lies, I’m at war with the mass media.” P-Orridge, who has died of leukaemia aged 70, stuck to the task of delivering aesthetic shocks and trampling over cultural taboos with impressive dedication and across multiple disciplines.

Perhaps best known for work with the bands Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV, P-Orridge, who used s/he as a pronoun, wrote songs about mass murder, mutilation, the occult and fascism. Throbbing Gristle’s track Zyklon B Zombie was a reference to the poison gas used in the Nazi death camps. Hamburger Lady (from their 1978 album DOA) was inspired by the story of a burns victim.

Unstintingly harsh and abrasive, Throbbing Gristle nonetheless built a select but dedicated following. Their album 20 Jazz Funk Greats (1979) – an exercise in Germanic electro-pop rather than jazz-funk – took them to No 6 on the UK indie chart.

Psychic TV, in whose oeuvre a playful pop music sensibility could be discerned, among experiments with electronic noise, psychedelia and droning repetition, seemed to favour subtle infiltration rather than the bludgeoning approach of Throbbing Gristle. They reached 67 on the UK pop chart in 1986 with Godstar, a song about the death of the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones. More remarkable was their project, starting in 1986, to record a live album on the 23rd of each month for 23 months. They managed 14 in 18 months, but this was enough to earn them a Guinness World Records entry.

Adam Sweeting

Published on Sun 15 Mar 2020

“I am at war with the status quo of society and I am at war with those in control and power,” said Genesis P-Orridge in 1989. “I’m at war with hypocrisy and lies, I’m at war with the mass media.” P-Orridge, who has died of leukaemia aged 70, stuck to the task of delivering aesthetic shocks and trampling over cultural taboos with impressive dedication and across multiple disciplines.

Perhaps best known for work with the bands Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV, P-Orridge, who used s/he as a pronoun, wrote songs about mass murder, mutilation, the occult and fascism. Throbbing Gristle’s track Zyklon B Zombie was a reference to the poison gas used in the Nazi death camps. Hamburger Lady (from their 1978 album DOA) was inspired by the story of a burns victim.

Unstintingly harsh and abrasive, Throbbing Gristle nonetheless built a select but dedicated following. Their album 20 Jazz Funk Greats (1979) – an exercise in Germanic electro-pop rather than jazz-funk – took them to No 6 on the UK indie chart.

Psychic TV, in whose oeuvre a playful pop music sensibility could be discerned, among experiments with electronic noise, psychedelia and droning repetition, seemed to favour subtle infiltration rather than the bludgeoning approach of Throbbing Gristle. They reached 67 on the UK pop chart in 1986 with Godstar, a song about the death of the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones. More remarkable was their project, starting in 1986, to record a live album on the 23rd of each month for 23 months. They managed 14 in 18 months, but this was enough to earn them a Guinness World Records entry.

Genesis P-Orridge with Throbbing Gristle performing at the Coachella Valley festival in Indio, California, in 2009. Photograph: Axel Koester/Corbis/Getty Images

But music was only one of the ways in which P-Orridge channelled their creative energies. Psychic TV made their debut in 1982 at a four-day multimedia event in London and Manchester called the Final Academy, which featured artists including William S Burroughs and Brion Gysin – whose cut-up writing technique had been a powerful influence on P-Orridge – in a mix of music, literature, film and video. In 1969, P-Orridge had begun laying the groundwork for future explorations by forming COUM Transmissions, a group based in Hull who performed improvised theatre and music shows. They adopted a logo of a partially erect penis, and infused their work with Dada-inspired absurdity.

They became successful enough to win grants from the Yorkshire Arts Association, the Arts Council of Great Britain and the British Council, though this did not bring with it a yearning for respectability. Their performances became increasingly extreme, featuring body-cutting and involving P-Orridge and Cosey Fanni Tutti (AKA Christine Carol Newby) having sex onstage. In her autobiography Art Sex Music (2017), Fanni Tutti made allegations that P-Orridge had been a violent and manipulative partner, which were denied by P-Orridge.

Throbbing Gristle was founded on 3 September 1975 (on the 36th anniversary of Britain declaring war on Germany), comprising Tutti and P-Orridge alongside Chris Carter and Peter Christopherson, and for a time continued alongside COUM.

COUM’s show Prostitution, staged at the ICA in London in 1976, provoked uproar with its pornographic images, sculptures fashioned from used tampons and transvestite security guards, prompting the Scottish Conservative MP Sir Nicholas Fairbairn to describe P-Orridge and Tutti as “wreckers of civilisation”.

P-Orridge was born Neil Megson in Longsight, Manchester, the child of Muriel and Ronald Megson. Ronald was a travelling salesman, jazz drummer and former actor who had survived Dunkirk with the British Army in 1940. The family moved to Essex, then later to Cheshire, where Neil attended Gatley primary school and won a scholarship to Stockport grammar school. In 1964 Neil was sent to the private Solihull school.

There tastes for literature and the avant-garde were developed and Neil became fascinated with the writings of the magician and occultist Aleister Crowley. (In 1981 Neil would form Thee Temple Ov Psychick Youth, an association of occultists.) In 1965 Neil founded his first band, Worm, with some school friends. They recorded an album, Early Worm (1968), but only one vinyl copy of it was produced.

In 1968, Neil went to Hull University to study social administration and philosophy, but dropped out the following year and moved to London joining the Transmedia Explorations commune in Islington. By the end of 1969 Neil was back in Hull, where COUM Transmissions was developed with John Shapeero.

The later phases of P-Orridge’s life were in some ways the most startling. P-Orridge moved to the US in the 1990s, following allegations (that subsequently proved false) in a Channel 4 Dispatches documentary that s/he had been involved in satanic ritual abuse.

In 1993 P-Orridge met Jacqueline Breyer, who was working at a New York S&M dungeon. She adopted the name Lady Jaye Breyer P-Orridge, and they moved in together in Queens, New York. They married in California in 1995, the year that P-Orridge was badly injured while escaping a fire at the Los Angeles home of the record producer Rick Rubin. He was awarded $1.5m compensation in 1998.

The couple set about using plastic surgery to become mirror images of one another, beginning with matching breast implants on Valentine’s Day 2003, and continuing with work on eyes and nose, liposuction and hormone therapy. They dressed in identical outfits, and P-Orridge coined the term “pandrogyny” to express the idea that they fused into a third person, Breyer P-Orridge, who only existed when they were together. P-Orridge subsequently preferred the self-descriptor “we”, though did not object to being called “s/he”.

This pandrogyny project was cut short when Breyer died of acute heart arrhythmia in 2007, an especially painful loss at a time when P-Orridge was beginning to receive highbrow acclaim. The Invisible-Exports gallery in New York staged a retrospective of their collages, 30 Years of Being Cut Up, and in 2009 Tate Britain purchased their archive.

Marie Losier’s documentary film The Ballad of Genesis and Lady Jaye was released in 2011, and in 2016 the Rubin Museum of Art in New York hosted Try to Altar Everything, an exhibition of P-Orridge’s paintings, sculptures and installations. In 2018 s/he published Brion Gysin: His Name Was Master, a collection of interviews and essays.

In 2003 P-Orridge had unveiled PTV3, a new band drawing on the legacy of Psychic TV. They released four albums and several EPs between 2007 and 2016. In 2018 they performed at Heaven in London.

P-Orridge is survived by two daughters, Genesse and Caresse, from a first marriage, to Paula Brooking, which ended in divorce.

• Genesis P-Orridge (Neil Andrew Megson), musician, writer and performance artist, born 22 February 1950; died 14 March 2020

Genesis P-Orridge

Genesis P-Orridge: troubling catalyst who loathed rock yet changed it for ever

But music was only one of the ways in which P-Orridge channelled their creative energies. Psychic TV made their debut in 1982 at a four-day multimedia event in London and Manchester called the Final Academy, which featured artists including William S Burroughs and Brion Gysin – whose cut-up writing technique had been a powerful influence on P-Orridge – in a mix of music, literature, film and video. In 1969, P-Orridge had begun laying the groundwork for future explorations by forming COUM Transmissions, a group based in Hull who performed improvised theatre and music shows. They adopted a logo of a partially erect penis, and infused their work with Dada-inspired absurdity.

They became successful enough to win grants from the Yorkshire Arts Association, the Arts Council of Great Britain and the British Council, though this did not bring with it a yearning for respectability. Their performances became increasingly extreme, featuring body-cutting and involving P-Orridge and Cosey Fanni Tutti (AKA Christine Carol Newby) having sex onstage. In her autobiography Art Sex Music (2017), Fanni Tutti made allegations that P-Orridge had been a violent and manipulative partner, which were denied by P-Orridge.

Throbbing Gristle was founded on 3 September 1975 (on the 36th anniversary of Britain declaring war on Germany), comprising Tutti and P-Orridge alongside Chris Carter and Peter Christopherson, and for a time continued alongside COUM.

COUM’s show Prostitution, staged at the ICA in London in 1976, provoked uproar with its pornographic images, sculptures fashioned from used tampons and transvestite security guards, prompting the Scottish Conservative MP Sir Nicholas Fairbairn to describe P-Orridge and Tutti as “wreckers of civilisation”.

P-Orridge was born Neil Megson in Longsight, Manchester, the child of Muriel and Ronald Megson. Ronald was a travelling salesman, jazz drummer and former actor who had survived Dunkirk with the British Army in 1940. The family moved to Essex, then later to Cheshire, where Neil attended Gatley primary school and won a scholarship to Stockport grammar school. In 1964 Neil was sent to the private Solihull school.

There tastes for literature and the avant-garde were developed and Neil became fascinated with the writings of the magician and occultist Aleister Crowley. (In 1981 Neil would form Thee Temple Ov Psychick Youth, an association of occultists.) In 1965 Neil founded his first band, Worm, with some school friends. They recorded an album, Early Worm (1968), but only one vinyl copy of it was produced.

In 1968, Neil went to Hull University to study social administration and philosophy, but dropped out the following year and moved to London joining the Transmedia Explorations commune in Islington. By the end of 1969 Neil was back in Hull, where COUM Transmissions was developed with John Shapeero.

The later phases of P-Orridge’s life were in some ways the most startling. P-Orridge moved to the US in the 1990s, following allegations (that subsequently proved false) in a Channel 4 Dispatches documentary that s/he had been involved in satanic ritual abuse.

In 1993 P-Orridge met Jacqueline Breyer, who was working at a New York S&M dungeon. She adopted the name Lady Jaye Breyer P-Orridge, and they moved in together in Queens, New York. They married in California in 1995, the year that P-Orridge was badly injured while escaping a fire at the Los Angeles home of the record producer Rick Rubin. He was awarded $1.5m compensation in 1998.

The couple set about using plastic surgery to become mirror images of one another, beginning with matching breast implants on Valentine’s Day 2003, and continuing with work on eyes and nose, liposuction and hormone therapy. They dressed in identical outfits, and P-Orridge coined the term “pandrogyny” to express the idea that they fused into a third person, Breyer P-Orridge, who only existed when they were together. P-Orridge subsequently preferred the self-descriptor “we”, though did not object to being called “s/he”.

This pandrogyny project was cut short when Breyer died of acute heart arrhythmia in 2007, an especially painful loss at a time when P-Orridge was beginning to receive highbrow acclaim. The Invisible-Exports gallery in New York staged a retrospective of their collages, 30 Years of Being Cut Up, and in 2009 Tate Britain purchased their archive.

Marie Losier’s documentary film The Ballad of Genesis and Lady Jaye was released in 2011, and in 2016 the Rubin Museum of Art in New York hosted Try to Altar Everything, an exhibition of P-Orridge’s paintings, sculptures and installations. In 2018 s/he published Brion Gysin: His Name Was Master, a collection of interviews and essays.

In 2003 P-Orridge had unveiled PTV3, a new band drawing on the legacy of Psychic TV. They released four albums and several EPs between 2007 and 2016. In 2018 they performed at Heaven in London.

P-Orridge is survived by two daughters, Genesse and Caresse, from a first marriage, to Paula Brooking, which ended in divorce.

• Genesis P-Orridge (Neil Andrew Megson), musician, writer and performance artist, born 22 February 1950; died 14 March 2020

Genesis P-Orridge

Genesis P-Orridge: troubling catalyst who loathed rock yet changed it for ever

Alexis Petridis

With Throbbing Gristle, P-Orridge inadvertently helped invent an entire genre – industrial music

Sun 15 Mar 2020

With Throbbing Gristle, P-Orridge inadvertently helped invent an entire genre – industrial music

Sun 15 Mar 2020

‘Presaging everything from acid house to the

ongoing conversation about gender fluidity’ ...

Genesis P-Orridge. Photograph: Neville Elder/Redferns

For someone who occasionally purported to hate rock music – it was, a homemade T-shirt s/he was fond of wearing in the 1970s proclaimed, “for arselickers” – Genesis Breyer P-Orridge ended up having a vast influence on it. With Throbbing Gristle, P-Orridge inadvertently helped invent an entire genre – industrial music, its name taken from the band’s Industrial record label – which, over the years, developed and mutated from a misunderstood and frequently reviled cult into a platinum-selling concern.

Intent on, as one writer put it, “bursting open the blistered lie [that] rock and roll culture was telling about rebellion and transgression”, virtually every one of Throbbing Gristle’s radical, confrontational ideas was gradually subsumed into something approaching the mainstream. Electronic producers queued up to pay homage to the band, whose resident technical wizard Chris Carter may or may not have invented the first sampler by dismantling a series of cassette recorders and linking them to bandmate Peter Christopherson’s keyboard: Detroit techno pioneer Carl Craig named a 1991 EP Four Jazz Funk Classics in homage to TG’s 1979 album 20 Jazz Funk Greats.

Twenty years after they caused disquiet by writing songs about serial killers and toying with quasi-Nazi imagery, one of the biggest rock stars in the world was called Marilyn Manson: on his Antichrist Superstar tour, performed in front of a huge logo that looked remarkably similar to TG’s trademark thunderflash, with its echoes both of high-voltage warning signs and, more queasily, the symbol of the British Union of Fascists. If P-Orridge’s later work with Psychic TV is less celebrated, it nevertheless demonstrated h/er uncanny ability to think ahead of the curve, presaging everything from acid house to the ongoing conversation about gender fluidity.

For someone who occasionally purported to hate rock music – it was, a homemade T-shirt s/he was fond of wearing in the 1970s proclaimed, “for arselickers” – Genesis Breyer P-Orridge ended up having a vast influence on it. With Throbbing Gristle, P-Orridge inadvertently helped invent an entire genre – industrial music, its name taken from the band’s Industrial record label – which, over the years, developed and mutated from a misunderstood and frequently reviled cult into a platinum-selling concern.

Intent on, as one writer put it, “bursting open the blistered lie [that] rock and roll culture was telling about rebellion and transgression”, virtually every one of Throbbing Gristle’s radical, confrontational ideas was gradually subsumed into something approaching the mainstream. Electronic producers queued up to pay homage to the band, whose resident technical wizard Chris Carter may or may not have invented the first sampler by dismantling a series of cassette recorders and linking them to bandmate Peter Christopherson’s keyboard: Detroit techno pioneer Carl Craig named a 1991 EP Four Jazz Funk Classics in homage to TG’s 1979 album 20 Jazz Funk Greats.

Twenty years after they caused disquiet by writing songs about serial killers and toying with quasi-Nazi imagery, one of the biggest rock stars in the world was called Marilyn Manson: on his Antichrist Superstar tour, performed in front of a huge logo that looked remarkably similar to TG’s trademark thunderflash, with its echoes both of high-voltage warning signs and, more queasily, the symbol of the British Union of Fascists. If P-Orridge’s later work with Psychic TV is less celebrated, it nevertheless demonstrated h/er uncanny ability to think ahead of the curve, presaging everything from acid house to the ongoing conversation about gender fluidity.

California, 22 May 1981. Photograph:

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

P-Orridge formed h/er first band, Worm, when s/he was still Neil Megson, a Manchester-born pupil at Solihull Public School. Worm even recorded an album, pressing up a solitary copy in 1968. If nothing else, it revealed that P-Orridge’s approach to music was defiantly left-field from the start: noise, improvisations and tape experiments mixed with songs that sounded a little like a less adept, more chaotic version of psychedelic folkies the Incredible String Band. When s/he moved to Hull, adopted the pseudonym Genesis P-Orridge and set up performance art group Coum with h/er partner, Christine Newby, who was re-christened Cosey Fanni Tutti, they too were initially music-based, albeit in the widest sense of the phrase.

They performed chaotic, tuneless, unrehearsed gigs, including one supporting Hawkwind where they chanted “off off off” from the stage to prefigure the audience’s inevitable response. Despite the enthusiasm of DJ John Peel, who plugged the band in his Disc and Music Echo column, Coum’s interest in music seemed to wane as h/er art became less playful and more disturbing: from brightly costumed actions on the streets of Hull that occasionally attracted crowds of entranced children, h/er performances shifted and began involving live sex acts, violence and much spilling of bodily fluids.

It wasn’t until P-Orridge and Tutti met former sound engineer Chris Carter that they were able to make music that reflected Coum’s bleak latterday vision, while enabling them to break out of an art world they increasingly derided as sterile and elitist. With Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson – a photographer and record sleeve designer who had taken part in some of Coum’s later performances – on keyboards, the early Throbbing Gristle dealt in churning noise, punishing electronic rhythms and distorted vocals that dealt with a variety of distressing topics: the Moors Murders, the Nazi holocaust, the acts of mutilation and barbarism described in Slug Bait.

They started playing gigs, to a largely apoplectic response: shows at regular rock venues frequently degenerated into violent confrontations with the audience. They performed at London’s ICA as part of the Coum retrospective exhibition Prostitution, which provoked such outrage that questions were asked in Parliament – Tory MP Nicholas Fairbairn provided Throbbing Gristle with their lasting epigraph by describing them as “wreckers of civilisation” – and the venue’s Arts Council funding was cut. Perhaps understandably, the band did not expect their murky, lo-fi, self-released debut album Second Annual Report to be a success: if it wasn’t entirely without precedent – you could hear in it echoes of Yoko Ono and John Lennon’s experimental work, the German avant-garde rock bands of the early 70s, the Velvet Underground circa White Light/White Heat and Lou Reed’s notorious Metal Machine Music – it was nevertheless incredibly extreme for its era. But not only did its initial pressing of 750 copies sell out, it seemed to act as a lightning rod for other artists who had coincidentally been thinking along similar musical lines, many of whom ended up being released by Industrial: Sheffield’s Cabaret Voltaire and Clock DVA, Australia’s SPK and Germany’s Leather Nun.

Throbbing Gristle proved to be a more expansive and diverse band than the unsettling din of Second Annual Report suggested. They followed it up with United, an alternately creepy and oddly sweet-sounding electronic single that foreshadowed the synth-led direction that mainstream pop would take in the early 80s: their subsequent albums took in everything from experiments with dark ambience, warped pop songs, audio collages and tracks that now sound remarkably like techno five years too early, while continually picking away at unpleasant subject matter. At its best, their work had a startling originality and power: 42 years after it first appeared on 1978’s DOA: The Third and Final Report, Hamburger Lady’s eerie, hushed retelling of the plight of a burns victim remains a genuinely terrifying piece of music.

Throbbing Gristle were never going to be anything other than divisive, as evidenced by the contemporary critical reaction, but they developed an increasingly fanatical cult following, with Joy Division frontman Ian Curtis among their ranks. Some of TG’s members professed to be horrified by their popularity – “I don’t like acceptance, I distrust it completely,” said Tutti – but P-Orridge set about moulding their fanbase into a quasi-paramilitary cult. S/he began referring to their gigs as “rallies” and sending out literature asking: “Do you want to become a fully-equipped Terror Guard? Ready for action? NOTHING SHORT OF A TOTAL WAR”; their 1981 single Discipline bore the legend “marching music for psychic youth”. By the time of their rancorous split, shortly after Discipline’s release, there was a burgeoning underground scene of new artists exploring similar musical and thematic areas: Current 93, Whitehouse, Nurse With Wound, Foetus, Test Department. Some were TG acolytes, some professed to loathe them and have no connection to their work: either way, it was impossible to see how said scene could have existed had Throbbing Gristle not existed first.

P-Orridge formed Psychic TV with, among others, Christopherson and his partner John Balance. They unexpectedly signed to a major label; more unexpected still, their 1982 debut album, Force the Hand of Chance, was frequently lush, melodic and strangely romantic. Its sleeve, however, bore the words: “File under: fundraising activities”. P-Orridge viewed Psychic TV as the musical wing of Thee Temple Ov Psychic Youth, which, depending on your perspective, was either an organisation dedicated to disseminating information about magickal practices – some derived from Aleister Crowley, others from occultist Austin Osman Spare – a satire on organised religion, or something approaching a cult, with P-Orridge its leader.

The latter was an accusation frequently levelled by ex-members of Psychic TV, including Christopherson and Balance, who left after 1983’s alternately cinematic and chilling Dreams Less Sweet to concentrate on their own project, the hugely acclaimed Coil. Their departure set the tone for a certain turbulence among Psychic TV’s personnel: P-Orridge never failed to attract interesting collaborators – there’s a credible argument that his greatest talent lay as a catalyst – but members perpetually came and left, frequently in acrimony, occasionally claiming that P-Orridge had taken credit for their work or ripped them off financially.

Psychic TV’s subsequent releases were never quite as musically compelling, although you couldn’t fault their eclecticism, nor P-Orridge’s willingness to spring surprises on his audience. Perhaps the biggest shock came when Psychic TV reinvented themselves as a relatively straightforward psychedelic rock band – P-Orridge having presumably decided that rock and roll wasn’t for arselickers as long as he was doing it – with decidedly mixed results: their cover of the Beach Boys’ Good Vibrations was an impressive act of chutzpah given P-Orridge’s limited vocal ability, though they grazed the lower reaches of the charts with Godstar, a charming and remarkably catchy paean to late Rolling Stones guitarist Brian Jones.

P-Orridge formed h/er first band, Worm, when s/he was still Neil Megson, a Manchester-born pupil at Solihull Public School. Worm even recorded an album, pressing up a solitary copy in 1968. If nothing else, it revealed that P-Orridge’s approach to music was defiantly left-field from the start: noise, improvisations and tape experiments mixed with songs that sounded a little like a less adept, more chaotic version of psychedelic folkies the Incredible String Band. When s/he moved to Hull, adopted the pseudonym Genesis P-Orridge and set up performance art group Coum with h/er partner, Christine Newby, who was re-christened Cosey Fanni Tutti, they too were initially music-based, albeit in the widest sense of the phrase.

They performed chaotic, tuneless, unrehearsed gigs, including one supporting Hawkwind where they chanted “off off off” from the stage to prefigure the audience’s inevitable response. Despite the enthusiasm of DJ John Peel, who plugged the band in his Disc and Music Echo column, Coum’s interest in music seemed to wane as h/er art became less playful and more disturbing: from brightly costumed actions on the streets of Hull that occasionally attracted crowds of entranced children, h/er performances shifted and began involving live sex acts, violence and much spilling of bodily fluids.

It wasn’t until P-Orridge and Tutti met former sound engineer Chris Carter that they were able to make music that reflected Coum’s bleak latterday vision, while enabling them to break out of an art world they increasingly derided as sterile and elitist. With Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson – a photographer and record sleeve designer who had taken part in some of Coum’s later performances – on keyboards, the early Throbbing Gristle dealt in churning noise, punishing electronic rhythms and distorted vocals that dealt with a variety of distressing topics: the Moors Murders, the Nazi holocaust, the acts of mutilation and barbarism described in Slug Bait.

They started playing gigs, to a largely apoplectic response: shows at regular rock venues frequently degenerated into violent confrontations with the audience. They performed at London’s ICA as part of the Coum retrospective exhibition Prostitution, which provoked such outrage that questions were asked in Parliament – Tory MP Nicholas Fairbairn provided Throbbing Gristle with their lasting epigraph by describing them as “wreckers of civilisation” – and the venue’s Arts Council funding was cut. Perhaps understandably, the band did not expect their murky, lo-fi, self-released debut album Second Annual Report to be a success: if it wasn’t entirely without precedent – you could hear in it echoes of Yoko Ono and John Lennon’s experimental work, the German avant-garde rock bands of the early 70s, the Velvet Underground circa White Light/White Heat and Lou Reed’s notorious Metal Machine Music – it was nevertheless incredibly extreme for its era. But not only did its initial pressing of 750 copies sell out, it seemed to act as a lightning rod for other artists who had coincidentally been thinking along similar musical lines, many of whom ended up being released by Industrial: Sheffield’s Cabaret Voltaire and Clock DVA, Australia’s SPK and Germany’s Leather Nun.

Throbbing Gristle proved to be a more expansive and diverse band than the unsettling din of Second Annual Report suggested. They followed it up with United, an alternately creepy and oddly sweet-sounding electronic single that foreshadowed the synth-led direction that mainstream pop would take in the early 80s: their subsequent albums took in everything from experiments with dark ambience, warped pop songs, audio collages and tracks that now sound remarkably like techno five years too early, while continually picking away at unpleasant subject matter. At its best, their work had a startling originality and power: 42 years after it first appeared on 1978’s DOA: The Third and Final Report, Hamburger Lady’s eerie, hushed retelling of the plight of a burns victim remains a genuinely terrifying piece of music.

Throbbing Gristle were never going to be anything other than divisive, as evidenced by the contemporary critical reaction, but they developed an increasingly fanatical cult following, with Joy Division frontman Ian Curtis among their ranks. Some of TG’s members professed to be horrified by their popularity – “I don’t like acceptance, I distrust it completely,” said Tutti – but P-Orridge set about moulding their fanbase into a quasi-paramilitary cult. S/he began referring to their gigs as “rallies” and sending out literature asking: “Do you want to become a fully-equipped Terror Guard? Ready for action? NOTHING SHORT OF A TOTAL WAR”; their 1981 single Discipline bore the legend “marching music for psychic youth”. By the time of their rancorous split, shortly after Discipline’s release, there was a burgeoning underground scene of new artists exploring similar musical and thematic areas: Current 93, Whitehouse, Nurse With Wound, Foetus, Test Department. Some were TG acolytes, some professed to loathe them and have no connection to their work: either way, it was impossible to see how said scene could have existed had Throbbing Gristle not existed first.

P-Orridge formed Psychic TV with, among others, Christopherson and his partner John Balance. They unexpectedly signed to a major label; more unexpected still, their 1982 debut album, Force the Hand of Chance, was frequently lush, melodic and strangely romantic. Its sleeve, however, bore the words: “File under: fundraising activities”. P-Orridge viewed Psychic TV as the musical wing of Thee Temple Ov Psychic Youth, which, depending on your perspective, was either an organisation dedicated to disseminating information about magickal practices – some derived from Aleister Crowley, others from occultist Austin Osman Spare – a satire on organised religion, or something approaching a cult, with P-Orridge its leader.

The latter was an accusation frequently levelled by ex-members of Psychic TV, including Christopherson and Balance, who left after 1983’s alternately cinematic and chilling Dreams Less Sweet to concentrate on their own project, the hugely acclaimed Coil. Their departure set the tone for a certain turbulence among Psychic TV’s personnel: P-Orridge never failed to attract interesting collaborators – there’s a credible argument that his greatest talent lay as a catalyst – but members perpetually came and left, frequently in acrimony, occasionally claiming that P-Orridge had taken credit for their work or ripped them off financially.

Psychic TV’s subsequent releases were never quite as musically compelling, although you couldn’t fault their eclecticism, nor P-Orridge’s willingness to spring surprises on his audience. Perhaps the biggest shock came when Psychic TV reinvented themselves as a relatively straightforward psychedelic rock band – P-Orridge having presumably decided that rock and roll wasn’t for arselickers as long as he was doing it – with decidedly mixed results: their cover of the Beach Boys’ Good Vibrations was an impressive act of chutzpah given P-Orridge’s limited vocal ability, though they grazed the lower reaches of the charts with Godstar, a charming and remarkably catchy paean to late Rolling Stones guitarist Brian Jones.

Photograph: Jim Dyson/Getty Images

They then shifted into acid house, or at least something like it: an enthusiastic consumer of hallucinogens, P-Orridge had heard the term, but none of the music. P-Orridge devotees are fond of making lofty claims for the results – initially released as a fake compilation album, Jack the Tab – but in truth “the first British acid house album” betrays its origins: a hastily thrown-together cocktail of electronic beats and samples from 60s exploitation movies, it patently wasn’t going to give any of acid house’s actual progenitors sleepless nights. Never popular with British clubbers or DJs, Psychic TV’s subsequent acid house albums – Towards Thee Infinite Beat and the remix collection Beyond Thee Infinite Beat – fared better in the US: the band played raves in California and looked at one stage to have secured a major label deal.

The latter fell through, but by then P-Orridge had bigger problems: falsely accused of ritual Satanic abuse in a bizarre 1992 Channel 4 documentary made by a Christian fundamentalist group, s/he went into self-imposed exile in the US. Initially, s/he continued releasing albums as Psychic TV – the electronic collages of the Electric Newspaper series, the return to psychedelic rock of 1996’s Trip Reset – but seemed to be gradually losing interest in music: h/er next project, Thee Majesty, featured P-Orridge reading and improvising poetry over experimental soundscapes.

S/he reactivated the Psychic TV name in 2003 – an all-new line-up featuring h/er second wife, Jacqueline Breyer, with whom P-Orridge embarked on the “pandrogeny project”, involving gender neutrality and body modification to look more like each other. Nick Zinner of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs contributed to the 2006 album, Hell Is Invisible, Heaven Is Her/e, but more attention was attracted by the reunion of Throbbing Gristle.

The latter came as a considerable surprise: relations between the former members were famously strained, a state of affairs not much helped by Psychic TV playing a 1988 London gig as Throbbing Gristle Ltd, ostensibly to demonstrate that P-Orridge was the sole creative force behind the band and the others were, in his words, “dishonest parasitic bastards”. As it turned out, the reunion was as tempestuous as Throbbing Gristle’s initial incarnation. They played a series of acclaimed live shows and released a handful of interesting albums, but Cosey Fanni Tutti’s 2017 autobiography Art Sex Music depicted the reformed band in a state of almost perpetual conflict, with P-Orridge invariably at odds with the other members before suddenly quitting.

P-Orridge subsequently attempted to halt the release of Desertshore, a cover of Nico’s 1968 album recorded by Tutti, Carter and a series of guest vocalists as a tribute to Peter Christopherson, who died in 2010. Certainly, the album and an accompanying collection of improvisations recorded after h/er departure didn’t do much for P-Orridge’s assertion s/he was the band’s sole creative force: they were significantly better than anything the reformed TG had released while s/he was a member.

These were far from the most damaging claims made in Tutti’s harrowing memoir, which not only depicted P-Orridge as mentally and physically abusive and given to claiming authorship of others’ work, but baldly accused h/er of attempted murder: first attacking her with a knife, then throwing a breeze block at her from a balcony, narrowly missing her head. P-Orridge blithely dismissed the claims, which seemed to have little impact on h/er standing as a revered cult figure, partly because Tutti’s book wasn’t published in the US, where P-Orridge was permanently based: either those devotees who did read it chose not to believe what it said, or felt that s/he had spent so long engaged in transgressive activities that a further set of transgressions didn’t matter. Or perhaps they felt Genesis P-Orridge’s artistic achievements were so monumental that such revelations couldn’t impact on them. Whether history will posthumously agree remains to be seen: that Genesis P-Orridge played a role in changing the course of rock music, however, is beyond doubt.

They then shifted into acid house, or at least something like it: an enthusiastic consumer of hallucinogens, P-Orridge had heard the term, but none of the music. P-Orridge devotees are fond of making lofty claims for the results – initially released as a fake compilation album, Jack the Tab – but in truth “the first British acid house album” betrays its origins: a hastily thrown-together cocktail of electronic beats and samples from 60s exploitation movies, it patently wasn’t going to give any of acid house’s actual progenitors sleepless nights. Never popular with British clubbers or DJs, Psychic TV’s subsequent acid house albums – Towards Thee Infinite Beat and the remix collection Beyond Thee Infinite Beat – fared better in the US: the band played raves in California and looked at one stage to have secured a major label deal.

The latter fell through, but by then P-Orridge had bigger problems: falsely accused of ritual Satanic abuse in a bizarre 1992 Channel 4 documentary made by a Christian fundamentalist group, s/he went into self-imposed exile in the US. Initially, s/he continued releasing albums as Psychic TV – the electronic collages of the Electric Newspaper series, the return to psychedelic rock of 1996’s Trip Reset – but seemed to be gradually losing interest in music: h/er next project, Thee Majesty, featured P-Orridge reading and improvising poetry over experimental soundscapes.

S/he reactivated the Psychic TV name in 2003 – an all-new line-up featuring h/er second wife, Jacqueline Breyer, with whom P-Orridge embarked on the “pandrogeny project”, involving gender neutrality and body modification to look more like each other. Nick Zinner of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs contributed to the 2006 album, Hell Is Invisible, Heaven Is Her/e, but more attention was attracted by the reunion of Throbbing Gristle.

The latter came as a considerable surprise: relations between the former members were famously strained, a state of affairs not much helped by Psychic TV playing a 1988 London gig as Throbbing Gristle Ltd, ostensibly to demonstrate that P-Orridge was the sole creative force behind the band and the others were, in his words, “dishonest parasitic bastards”. As it turned out, the reunion was as tempestuous as Throbbing Gristle’s initial incarnation. They played a series of acclaimed live shows and released a handful of interesting albums, but Cosey Fanni Tutti’s 2017 autobiography Art Sex Music depicted the reformed band in a state of almost perpetual conflict, with P-Orridge invariably at odds with the other members before suddenly quitting.

P-Orridge subsequently attempted to halt the release of Desertshore, a cover of Nico’s 1968 album recorded by Tutti, Carter and a series of guest vocalists as a tribute to Peter Christopherson, who died in 2010. Certainly, the album and an accompanying collection of improvisations recorded after h/er departure didn’t do much for P-Orridge’s assertion s/he was the band’s sole creative force: they were significantly better than anything the reformed TG had released while s/he was a member.

These were far from the most damaging claims made in Tutti’s harrowing memoir, which not only depicted P-Orridge as mentally and physically abusive and given to claiming authorship of others’ work, but baldly accused h/er of attempted murder: first attacking her with a knife, then throwing a breeze block at her from a balcony, narrowly missing her head. P-Orridge blithely dismissed the claims, which seemed to have little impact on h/er standing as a revered cult figure, partly because Tutti’s book wasn’t published in the US, where P-Orridge was permanently based: either those devotees who did read it chose not to believe what it said, or felt that s/he had spent so long engaged in transgressive activities that a further set of transgressions didn’t matter. Or perhaps they felt Genesis P-Orridge’s artistic achievements were so monumental that such revelations couldn’t impact on them. Whether history will posthumously agree remains to be seen: that Genesis P-Orridge played a role in changing the course of rock music, however, is beyond doubt.

Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV leader Genesis Breyer P-Orridge dies aged 70

Co-founder of avant garde and experimental groups dies after long illness, leaving behind complicated legacy

Martin Belam Sat 14 Mar 2020

Genesis P Orridge in their 2014 exhibition at

Summerhall, Edinburgh. Photograph: Peter Dibdin/Publicity image

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, co-founder of avant-garde band Throbbing Gristle and leader of Psychic TV, has died aged 70, according to reports from their family.

Genesis’ daughters, Genesse and Caresse, stated their parent, who used s/he as a pronoun, died on 14 March, issuing the following statement via social media:

“Dear friends, family and loving supporters, it is with very heavy hearts that we announce the passing of our beloved father, Genesis Breyer P-Orridge. S/he had been battling leukaemia for two and a half years and dropped her body early this morning, Saturday 14th March, 2020. S/he will be laid to rest with h/er other half, Jacqueline ‘Lady Jaye’ Breyer who left us in 2007, where they will be re-united.”

Genesis P-Orridge: fantastic transgressor or sadistic aggressor?

P-Orridge had been diagnosed with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia in 2017, and in recent years had been touring farewell shows with Psychic TV, last playing in London and Berlin in 2018.

Born as Neil Andrew Megson in Manchester, Genesis Breyer P-Orridge grew up in Essex. S/he was a member of radical art collective COUM Transmissions in the late 1960s, and went on to form Throbbing Gristle with Cosey Fanni Tutti, Peter Christopherson and Chris Carter. The band’s three albums in the late 70s were considered landmarks of the industrial scene.

Godstar, Psychic TV’s tribute to Rolling Stones guitarist Brian Jones, came closest to delivering a pop anthem from an artist who had helped pioneer industrial sounds and then adopted trappings of psychedelia.

Godstar - Psychic TV

In recent years, the nature of P-Orridge’s work in Throbbing Gristle has been re-examined after Cosey Fanni Tutti’s biography revealed more about their relationship, and the sometimes physical danger she felt she was in while working in the collective. She claimed that at one point s/he nearly killed her, throwing a breeze block at her from a balcony, narrowly missing her head. P-Orridge always denied the allegations.

Genesis P-Orridge: fantastic transgressor or sadistic aggressor?

The music essay Genesis P-Orridge

The Throbbing Gristle provocateur is being hymned as she nears the end of her life. But accusations of abuse, all denied, complicate her legacy

Lottie Brazier Tue 11 Dec 2018

A new kind of human relationship ... Genesis P-Orridge.

Photograph: Peter Dibdin

Last month, industrial performance artist and provocateur Genesis P-Orridge performed her final concert at London venue Heaven. It wasn’t just a farewell to her audience, but also a means for Genesis P-Orridge to bid farewell to herself. Recently she told the New York Times that the course of her chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia meant that she had “less optimistically, a year, maybe six months. And then I’m on the downward slope to death”. As with the Fall’s Mark E Smith in January this year, it’s difficult to imagine the UK music underground without this constant fixture.

Roughly half a century ago, Genesis P-Orridge flitted between several artist collectives. After dropping out of Hull university, she met avant-garde performance artist Cosey Fanni Tutti before joining the Ho Ho Funhouse art collective in London. Then a couple, the pair created the supposedly egalitarian, hippy collective COUM Transmissions and developed keen ideas around art’s purpose in society: namely, “art as life”. Fanni Tutti, Chris Carter and Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson and P-Orridge formed the industrial noise project Throbbing Gristle, who vowed never to rehash their albums live, aimed to be more antagonistic than punk and were bestowed the title “wreckers of civilisation” by Conservative MP Nicholas Fairbairn following their pornographic Prostitution exhibition at London’s ICA in 1976. Seeking to juxtapose the monotonous sounds of factory work coupled with controversial reappropriation of totalitarian symbolism, Throbbing Gristle gave Genesis P-Orridge her reputation as the “godperson of industrial music”. An extraordinary life, no doubt – but to what extent can it be celebrated?

That recent New York Times piece shows ambitious, radical bodily transgression to be the overarching theme of Genesis P-Orridge’s prolific creative life, a fascination that began with her teenage love of German dadaist artist Max Ernst’s surrealist corporeal mashup, The Hundred Headless Woman. P-Orridge would leave behind her past identity as Neil Andrew Megson, and, decades later, participate in body modification in order to become a cosmetic “double” of her partner, the nurse and dominatrix Lady Jaye, in what P-Orridge termed the Pandrogyne Project

Last month, industrial performance artist and provocateur Genesis P-Orridge performed her final concert at London venue Heaven. It wasn’t just a farewell to her audience, but also a means for Genesis P-Orridge to bid farewell to herself. Recently she told the New York Times that the course of her chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia meant that she had “less optimistically, a year, maybe six months. And then I’m on the downward slope to death”. As with the Fall’s Mark E Smith in January this year, it’s difficult to imagine the UK music underground without this constant fixture.

Roughly half a century ago, Genesis P-Orridge flitted between several artist collectives. After dropping out of Hull university, she met avant-garde performance artist Cosey Fanni Tutti before joining the Ho Ho Funhouse art collective in London. Then a couple, the pair created the supposedly egalitarian, hippy collective COUM Transmissions and developed keen ideas around art’s purpose in society: namely, “art as life”. Fanni Tutti, Chris Carter and Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson and P-Orridge formed the industrial noise project Throbbing Gristle, who vowed never to rehash their albums live, aimed to be more antagonistic than punk and were bestowed the title “wreckers of civilisation” by Conservative MP Nicholas Fairbairn following their pornographic Prostitution exhibition at London’s ICA in 1976. Seeking to juxtapose the monotonous sounds of factory work coupled with controversial reappropriation of totalitarian symbolism, Throbbing Gristle gave Genesis P-Orridge her reputation as the “godperson of industrial music”. An extraordinary life, no doubt – but to what extent can it be celebrated?

That recent New York Times piece shows ambitious, radical bodily transgression to be the overarching theme of Genesis P-Orridge’s prolific creative life, a fascination that began with her teenage love of German dadaist artist Max Ernst’s surrealist corporeal mashup, The Hundred Headless Woman. P-Orridge would leave behind her past identity as Neil Andrew Megson, and, decades later, participate in body modification in order to become a cosmetic “double” of her partner, the nurse and dominatrix Lady Jaye, in what P-Orridge termed the Pandrogyne Project

.

Genesis P-Orridge playing with Throbbing Gristle at YMCA, London, 3 August 1979. Photograph: David Corio/Redferns

Lady Jaye died in 2007, but P-Orridge continued with cosmetic surgery to alter her own body, part of her continuous striving to exist as a work of art. While P-Orridge and Lady Jaye might have conceived of a new kind of human relationship – a radical reconsideration of the self in relationship to another – it seemed strange that the New York Times didn’t consider P-Orridge’s status as body provocateur alongside Fanni Tutti’s allegations. In her 2017 autobiography Art Sex Music – she says P-Orridge was a manipulative, cruel partner. Fanni Tutti reveals another side to P-Orridge’s story, in which her own artistic freedoms and body, which she also considers interchangeable, are controlled and oppressed by her then-lover and bandmate.

Fanni Tutti recalls a series of alleged incidents in Art Sex Music, all denied by P-Orridge to the New York Times: how P-Orridge threw a concrete block at her head from a balcony, apparently aiming to kill her, and missed. How she allegedly pressured Fanni Tutti into frequent unprotected sex, which led her to seek an abortion. How she ran at her with a knife after Fanni Tutti threatened to end their relationship. How P-Orridge appointed herself chief supervisor of COUM’s frequent orgies and expected Fanni Tutti to have sex with various friends “instigated by and shared with [P-Orridge]”. There are repeat alleged incidences of P-Orridge forcing Fanni Tutti out of their shared living space.

The New York Times referenced Fanni Tutti’s allegations in a slim, sceptical paragraph. P-Orridge’s response: “Whatever sells a book sells a book.”

Cosey Fanni Tutti. Photograph: Linda Nylind/The Guardian

Former COUM member Foxtrot Echo also suggests in Art Sex Magic that P-Orridge’s genius didn’t lie in her artistic skills, but rather in her ability to manipulate others. One key COUM member, Spydee, left the group after confessing to Fanni Tutti his frustration that P-Orridge “just wanted followers, not people to contribute. [She was] very dominant, we had no fun.”

In an interview with the Quietus, Throbbing Gristle’s electronics supervisor Chris Carter admitted that this tension drove the group’s sound – at least until their first split in 1981, after P-Orridge departed. Still, it was Carter’s DIY circuitry that fuelled their constant experimentation and unpredictable live performances. Throbbing Gristle created a sublime terror through their combination of imagery and sound. This, they explained, was their attempt to reveal the hypocrisy of British conservative politics, to strip back the safeness and niceness of “ordinary society” to show what humanity was truly capable of. In the early 90s, Scotland Yard’s Obscene Publications Squad raided Genesis P-Orridge’s house and discovered a fascination with necrophilia, murder and Nazism; Genesis herself has reminisced about art performances involving enemas of blood, milk and urine, or masturbating with severed chicken heads.

In his book on the history of British esoteric music, England’s Hidden Reverse, David Keenan argues that: “To take morality so seriously you have to pick it apart yourself in order to rebuild it in the face of the truth of existence, in all its horror and beauty, is intensely moral.” But for some, adopting such imagery is still a seductive means to signal extremist allegiances, while operating under the veneer of explorative artistic “transgression”.

Genesis P-Orridge at an exhibition of her work at Summerhall, Edinburgh, 2014. Photograph: Peter Dibdin

After leaving Throbbing Gristle in 1981, Genesis P-Orridge’s new band Psychic TV at times adopted a more straightforward garage rock setup (though perhaps with a little ironic distance). One of their most well-known tracks, the scrappy, Buzzcocks-esque Godstar, had P-Orridge recount the tragic life of the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones, commenting on the shallowness and destruction of fame. This anti-pop pop song clawed its way into the UK charts, surely something P-Orridge would have sniffed at during the Throbbing Gristle days. Other Psychic TV works continue Throbbing Gristle’s sound collage approach, but they’re sorely lacking Chris Carter’s metal machine music – their track Discipline sounds as if it’s driven by the irregular heartbeat and screams of Linda Blair, the demonically possessed girl in The Exorcist.

Psychic TV has continued well through the 80s and P-Orridge has released 37 studio albums with the band since its conception. In 1993, P-Orridge moved with Lady Jaye to Ridgewood, Queens in New York where the pair began the Pandrogeny Project, identifying themselves singularly as “Breyer P-Orridge”. In a recent documentary by French director and curator Marie Losier, The Ballad of Genesis and Lady Jaye, P-Orridge is shown to be heartbroken, weak, struggling to pay the bills. But Losier allows P-Orridge to steer the course of the film away from the more controversial, problematic aspects of her early years – a celebration bordering on hagiography.

Artists that push for the representation of progressive lifestyles and new ways of framing identity should not be denied a platform, but their actions cannot be swept under the rug if they do not fit with their projected image – or even worse, glamorised as part of their transgression when they are plainly harmful. As Andrea Long Chu stated in her masterful disassembly of non-binary writer and director Jill Soloway’s memoir, She Wants It: Desire, Power, and Toppling the Patriarchy: “The ethics of gender recognition, now more than ever, compel us to accept without contest or prejudice the self-identification of all people. They do not, however, compel us to find those identities likable, interesting, or worth writing a book about.”

As the Quietus warn in their essay on extreme politics in underground music: “Artistic transgression and subversion are vital elements of any socially progressive culture, but mindlessly pushing against the boundaries of what is considered acceptable, artistically, politically, or socially, is not necessarily progress.” Legacies place an artist’s fingerprints on scenes and communities, that linger even in their absence, and P-Orridge is certainly interesting enough to write a book about. But Fanni Tutti’s accusations are now part of this legacy – and anyway, with such an unruly personality, P-Orridge herself would likely reject a straightforward, purely celebratory account of her life. Histories of our artists must be written honestly and sometimes even painfully – otherwise our civilisation will truly be wrecked.

Could it be magick? The occult returns to the art world

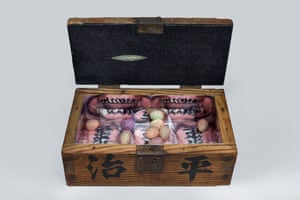

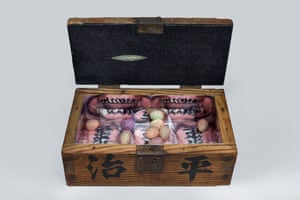

Blood Bunny: includes blood infused with ketamine. Photograph: Invisible Exports

Nearby are a small sculptural shrine with dried fish slathered in sparkles over an abstract mandala design (Feeding the Fishes, 2010) and an odd clock remade with fossil teeth, feathers and bits of gold alluding to alchemical forces (It’s All a Matter of Time, 2016).

Works of the sort in the show serve as reliquaries or tools for use in rituals rooted in a mixture of familiar religions (Buddhism, Hinduism, voodoo) and inclinations toward the more arcane realms of black magic and the occult.

“We’ve investigated lots of avenues and that includes occulture of various types,” says Breyer P-Orridge, who uses the word “we” exclusively in reference to a sort of individual and collective self. Early learning from occult figures like Aleister Crowley and mysterious magical sects like the Ordo Templi Orientis led to a lifelong devotion to ritualistic practice that has expanded and evolved.

S/he speaks highly still of “sex magic, where the orgasm is the moment when all forms of consciousness in your mind are joined, temporarily, and therefore you can pass a message through.” And other ceremonial endeavors involving age-old symbols and codes continue to be part of a method of art-making that is as much about the making as the end result.

Feeding the Fishes: a small sculptural shrine. Photograph: Invisible Exports

An essay in the catalog for the Rubin show refers to Breyer P-Orridge’s earliest work’s dedication to “the ‘discovery of intention’, meaning it created and unearthed its message and relevance through performance, not before,” while characterizing h/er ritual-abetted communion with Lady Jaye as a “living, experimental work of art in the process”.

Sign up to the Art Weekly email

Read more

The exhibition, which continues through 1 August, arrives in the midst of a certain vogue for art attuned to occult practices. Last fall, a survey of demonic and deranged paintings by Marjorie Cameron, an associate of notorious rocket-scientist/occultist Jack Parsons and film-maker Kenneth Anger, showed at the gallery of prominent New York art maven Jeffrey Deitch. A group show titled Language of the Birds: Occult and Art gathered work by the likes of Brion Gysin, Jordan Belson, Anohni, Lionel Ziprin, Carol Bove and many more (including Breyer P-Orridge) in the 80WSE Gallery at New York University. Uptown at the American Folk Art Museum, a show titled Mystery and Benevolence: Masonic and Odd Fellows Folk Art drew visitors before closing in May.

Enough interest has been fostered and fanned out to make one wonder about the source of it all. Is it a yearning for art made for purposes other than mere aesthetic enterprise? A desired deferral to forces other than those proffered by markets and asset-class finance deals? A curiosity about creations devised with a mind for matters at play outside internal dialogues within just the art world itself?

Bolts from the blue: art gets spooky. Photograph: MoMA

He insists, too, that they are not as anachronistic as many might suspect. “Everyone walks around with a matrix of beliefs through which they view the world,” Oursler says. “Statistically, if you look at America, it turns out roughly 60% of the population believes in ESP. One in three people do not believe in evolution. Forty percent of the public believes in UFOs. The rationalism we assume to be there might not, in fact, be there.”

Breyer P-Orridge attributes rising interest in the occult to certain fleeting motivations. “Some of it is pure fashion, always,” s/he says. But the role of ritual and faith in its own ends can be a guide. After growing weary of the hierarchies and conscriptions of ceremonial magic as practiced early on (see: robes, chants, gestures with strict limitations and rules), “We thought: Do you need all the fancy theatrics or is there something at the core that makes things happen? Our experience tells us it’s just one or two things at the core. One of those is being able to reprogram one’s deep consciousness through repetition in ritual.”

When a working sense of ritual conjoins with the process of making art, the result might be differently invested. “When we walk around to galleries, we’re nearly always disappointed,” Breyer P-Orridge says of art s/he sees around town. “Most of it is not about anything. It’s decorative at best and looks nice in penthouses. And now it’s gotten more corrupted because it’s like the stock market – people going around to advise people what to buy as an investment. You can’t trust the art world.”

To be trusted instead: “That strange reverberation that tells me what’s fascinating.”

This article was amended on 1 July 2016; the artist mentioned is Marjorie Cameron, not Carmen

This much I know

Genesis P-Orridge

Interview

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge: 'Pleasure is a weapon'

Interview

Genesis P-Orridge: 'People's lives should be as interesting as their art'Dave Simpson

The Throbbing Gristle founder, once branded a 'wrecker of civilisation', talks about being given a poetry prize by Philip Larkin and reaching marital unity through plastic surgery

Thu 29 Aug 2013

Genesis P-Orridge: 'The press portray me as outrageous, but we have a way with animals.' Photograph: Andy Kropa/Getty Images North America

Hi Genesis! Your new photographic retrospective book about your life contains images of nudity and genital mutilation. (1) Yet some fans might be more shocked by the one of you as a cute little boy clutching a rabbit.

For the first nine years of my life we (2) weren't allowed pets because of my asthma, apart from that rabbit, which lived outdoors in a hutch. But we've had dogs since 1969. The media portray me as outrageous, but we have a way with animals and can train dogs so well that they don't need leads. We once took the dog shopping, went home and two hours later thought: "Where's the fucking dog?" We ran back like a maniac and she was still there, sitting outside the butcher's.

How did cute little Neil Megson become the notorious Genesis P-Orridge?

Solihull School radicalised me in terms of who are the enemy. All the other kids were being told: "You are the future leaders of Britain. You will be MPs or military generals." Then there was me. We started an underground magazine complaining about the school rules and actually got some of them changed, like the one which insisted that boys of 6ft 4in with stubble should always wear their school cap. It was ridiculous!

Were you a bit of a handful, even then?

There's one of my old school reports in the book. The English teacher – nicknamed Bog Brush because of his moustache – put: "Neil seems to live in a completely different universe to the rest of us. Very weird but very intelligent." We'd been quoting Tibetan Buddhism in essays about Shakespeare and stuff. He did recommend Jack Kerouac's On The Road to me, though, which convinced me that people's lives should be as interesting as the art they make. A lifelong manifesto.

Were you really given a prize at Hull University by Philip Larkin?

We went there to study philosophy and economics. God knows why. Within three weeks we thought: "We can't do this." So we started writing poetry. Philip Larkin – the librarian there – gave me the prize, and not long afterwards told the Times I was the most promising young poet in Britain. Which, of course, immediately stopped me writing poetry.

Most people form bands to be famous, make money and have sex. What motivated you to form Throbbing Gristle?

Well, we were already getting plenty of sex! We'd been doing this thing called Coum Transmissions and I remember wearing gas masks outside Hull town hall and this guy in a suit rushing up asking: "Who are you people?" The British Council sent us to Milan with Gilbert and George to represent British performance art, but one day I was talking to this old man in the pub who'd been gassed in the first world war. He'd said: "I understand you're trying to wake people up. But how many people in this pub would get it? Why don't you do something accessible, like music?" So we did.

How did you invent industrial music, which became a genre that has since inspired everyone from David Bowie to Marilyn Manson to Nine Inch Nails?

It was a process of reduction. We decided we didn't want a drummer, because that would immediately anchor us in rock history. At the beginning, we hit my bass strings with a leather glove to provide a rhythm. Chris Carter started building drum machines and weird gadgets. Sleazy Christopherson experimented with tape machines and cut ups because he was into [William] Burroughs. Cosey [Fanni Tutti] wanted to play lead guitar, which at the time was unheard of for a woman. We got one from Woolworths, but she said it was too heavy. So we took an electric saw and cut off the excess wood. That's how she ended up with that style of guitar.

How did you write songs?

We jammed every weekend throughout 1975, recording everything and listening to it back so we could use the best bits. Later, we added my deadpan Lou Reed voice and the various stories. It was about taking lyrics and imagery to the logical conclusion. Nothing was too extreme. Nothing was taboo.

Your first performance – the notorious "Prostitution" show at the ICA in 1976 – catapulted you to national attention.

Yeah. We had a plastic art deco clock filled with used tampons called It's That Time of the Month. The whole country was in uproar. Now those tampons are in the Tate National Collection of Fine Art – with the Turners, the Rothkos and the Constables.'

How did it feel to be branded "wreckers of civilisation" in the House of Commons?

We were so proud. We had a flyer with that on it the very next day. The irony of it was that Sir Nicholas Fairbairn – the [Tory] MP who called us that – was involved in various sex scandals. And his mistress, a House of Commons secretary, tried to hang herself outside his office. It was classic British hypocrisy: everything we were against.

Is it true that TG's 20 Jazz Funk Greats album was returned to the shops by irate jazz funk fans compaining: "This isn't jazz funk. It's horrible noise!"?

There was a lot of dark, twisted humour in TG.

Your Twitter page says you're "STILL!" a member of TG. Does that mean the band still exists?

I never quit the band even though the others said I did. I just didn't do the last two gigs for reasons that will become clear eventually – it was the people around them on the business side. But Sleazy died not long after, so maybe it was the end of our natural life as a band.

TG and your other band Psychic TV both became international cults without entering the mainstream. Would you have liked hits?

Well Godstar (3) got to No 29. But going on Top of the Pops would have ruined everything. It would have made it much more difficult to write books, do art exhibitions and set up religions and be taken seriously. Once you have a hit, it just becomes another old song. Mick Jagger is 70 and still singing Satisfaction every concert. That would drive me insane.

Were you really the last person to speak to Joy Division's Ian Curtis before he killed himself?

Ian Curtis was a young genius. We were the last person he spoke to on the phone. He said: "I don't want to go on the American tour. I'd rather be dead." He sang our song Weeping – about suicide – down the phone. We were ringing people in Manchester, saying: "You've got to go round to Ian's because he's going to try and kill himself." The people we got through to went, "Oh, he's always being dramatic" and the other people were out. Even now it really upsets me.

In 1992, you were hounded from the UK by the tabloids and the police, amid allegations of "Satanic ritual abuse"? What happened?

Sleazy had made this film of young boys: LA skateboarders who meet this guy who puts an implant in their arms so every time they press a button they get an orgasm. After a while it burns out the nerves, so they put it in their cocks. It was all fake, but when I first saw it, I said: "Sleazy. People will think this is real."

So you aren't a Satanist, Gen?

That's so far from what we are. We were actually in Kathmandu using our own money to help Tibetan monks feed beggars and refugees when the papers called us "Satanists". Scotland Yard raided my house and took everything, then told my lawyers that if I'd tell them who made the film, they'd forget all about it. But we wouldn't snitch. We lost everything: two homes, our children gave up their friends. Sleazy never thanked me. That was disappointing.

You moved to America and met Lady Jaye Breyer (4), your second wife, musical collaborator and soulmate. Where did you find her?

In a friend's dungeon. We were in the middle of a not very pleasant divorce, so every so often we'd come to New York for a break and basically go wild. We were fast asleep with all these torture instruments after being awake for three days, woke up and this beautiful tall, slim girl wearing 60s clothing with a Brian Jones haircut walks past, then gets changed into this really sexy leather outfit. I was thinking: "Dear universe, if I can be with this woman for the rest of my life, that's all I want." She came over and we were in love from that moment. We got a windfall from a court case and rather than do what everyone else does and buy a Ferrari and a big house, we realised it meant we could be free to never work, just be in love and create things. Thank goodness, because we spent every minute together for the whole time she was physically on this planet. If we'd have done things the normal way, we'd have just seen each other at dinnertime when we were tired.

Why did you start pandrogyny [having plastic surgery to look the same as each other]?

Well, you know that moment when you meet someone and think: "I want to eat you, be immersed in you?" It began like that, and then we began to see more ramifications in terms of how society is controlled and evolution. Humans have to realise they're not individuals, but individual parts of the same organism, with responsibility to each other.

The photographs of Jaye and of you after her death (5) show a deeply moving, intimate side of you that the public has never seen. Was it difficult sifting through those photos?

My friend Leigha Mason selected them because it was impossible for me. My parents and all the animals in the photos apart from Musty, my Pekinese, are dead. Lady Jaye has dropped her body. We believe in reincarnation, but that was really hard.

Footnotes

(1) The book Genesis Breyer P-Orridge is published by First Third Books in deluxe and standard editions.

(2) Genesis usually refers to h/erself in the second person as "we".

(3) 1985 Psychic TV single, a tribute to dead Rolling Stone Brian Jones.

(4)Former nurse Jacqueline Breyer, also known as Miss Domination. After marriage Genesis adopted the name Genesis Breyer P-Orridge.

(5) In 2007, from a heart attack related to stomach cancer.

Genesis P-Orridge playing with Throbbing Gristle at YMCA, London, 3 August 1979. Photograph: David Corio/Redferns

Lady Jaye died in 2007, but P-Orridge continued with cosmetic surgery to alter her own body, part of her continuous striving to exist as a work of art. While P-Orridge and Lady Jaye might have conceived of a new kind of human relationship – a radical reconsideration of the self in relationship to another – it seemed strange that the New York Times didn’t consider P-Orridge’s status as body provocateur alongside Fanni Tutti’s allegations. In her 2017 autobiography Art Sex Music – she says P-Orridge was a manipulative, cruel partner. Fanni Tutti reveals another side to P-Orridge’s story, in which her own artistic freedoms and body, which she also considers interchangeable, are controlled and oppressed by her then-lover and bandmate.

Fanni Tutti recalls a series of alleged incidents in Art Sex Music, all denied by P-Orridge to the New York Times: how P-Orridge threw a concrete block at her head from a balcony, apparently aiming to kill her, and missed. How she allegedly pressured Fanni Tutti into frequent unprotected sex, which led her to seek an abortion. How she ran at her with a knife after Fanni Tutti threatened to end their relationship. How P-Orridge appointed herself chief supervisor of COUM’s frequent orgies and expected Fanni Tutti to have sex with various friends “instigated by and shared with [P-Orridge]”. There are repeat alleged incidences of P-Orridge forcing Fanni Tutti out of their shared living space.

The New York Times referenced Fanni Tutti’s allegations in a slim, sceptical paragraph. P-Orridge’s response: “Whatever sells a book sells a book.”

Cosey Fanni Tutti. Photograph: Linda Nylind/The Guardian

Former COUM member Foxtrot Echo also suggests in Art Sex Magic that P-Orridge’s genius didn’t lie in her artistic skills, but rather in her ability to manipulate others. One key COUM member, Spydee, left the group after confessing to Fanni Tutti his frustration that P-Orridge “just wanted followers, not people to contribute. [She was] very dominant, we had no fun.”

In an interview with the Quietus, Throbbing Gristle’s electronics supervisor Chris Carter admitted that this tension drove the group’s sound – at least until their first split in 1981, after P-Orridge departed. Still, it was Carter’s DIY circuitry that fuelled their constant experimentation and unpredictable live performances. Throbbing Gristle created a sublime terror through their combination of imagery and sound. This, they explained, was their attempt to reveal the hypocrisy of British conservative politics, to strip back the safeness and niceness of “ordinary society” to show what humanity was truly capable of. In the early 90s, Scotland Yard’s Obscene Publications Squad raided Genesis P-Orridge’s house and discovered a fascination with necrophilia, murder and Nazism; Genesis herself has reminisced about art performances involving enemas of blood, milk and urine, or masturbating with severed chicken heads.

In his book on the history of British esoteric music, England’s Hidden Reverse, David Keenan argues that: “To take morality so seriously you have to pick it apart yourself in order to rebuild it in the face of the truth of existence, in all its horror and beauty, is intensely moral.” But for some, adopting such imagery is still a seductive means to signal extremist allegiances, while operating under the veneer of explorative artistic “transgression”.

Genesis P-Orridge at an exhibition of her work at Summerhall, Edinburgh, 2014. Photograph: Peter Dibdin

After leaving Throbbing Gristle in 1981, Genesis P-Orridge’s new band Psychic TV at times adopted a more straightforward garage rock setup (though perhaps with a little ironic distance). One of their most well-known tracks, the scrappy, Buzzcocks-esque Godstar, had P-Orridge recount the tragic life of the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones, commenting on the shallowness and destruction of fame. This anti-pop pop song clawed its way into the UK charts, surely something P-Orridge would have sniffed at during the Throbbing Gristle days. Other Psychic TV works continue Throbbing Gristle’s sound collage approach, but they’re sorely lacking Chris Carter’s metal machine music – their track Discipline sounds as if it’s driven by the irregular heartbeat and screams of Linda Blair, the demonically possessed girl in The Exorcist.

Psychic TV has continued well through the 80s and P-Orridge has released 37 studio albums with the band since its conception. In 1993, P-Orridge moved with Lady Jaye to Ridgewood, Queens in New York where the pair began the Pandrogeny Project, identifying themselves singularly as “Breyer P-Orridge”. In a recent documentary by French director and curator Marie Losier, The Ballad of Genesis and Lady Jaye, P-Orridge is shown to be heartbroken, weak, struggling to pay the bills. But Losier allows P-Orridge to steer the course of the film away from the more controversial, problematic aspects of her early years – a celebration bordering on hagiography.

Artists that push for the representation of progressive lifestyles and new ways of framing identity should not be denied a platform, but their actions cannot be swept under the rug if they do not fit with their projected image – or even worse, glamorised as part of their transgression when they are plainly harmful. As Andrea Long Chu stated in her masterful disassembly of non-binary writer and director Jill Soloway’s memoir, She Wants It: Desire, Power, and Toppling the Patriarchy: “The ethics of gender recognition, now more than ever, compel us to accept without contest or prejudice the self-identification of all people. They do not, however, compel us to find those identities likable, interesting, or worth writing a book about.”

As the Quietus warn in their essay on extreme politics in underground music: “Artistic transgression and subversion are vital elements of any socially progressive culture, but mindlessly pushing against the boundaries of what is considered acceptable, artistically, politically, or socially, is not necessarily progress.” Legacies place an artist’s fingerprints on scenes and communities, that linger even in their absence, and P-Orridge is certainly interesting enough to write a book about. But Fanni Tutti’s accusations are now part of this legacy – and anyway, with such an unruly personality, P-Orridge herself would likely reject a straightforward, purely celebratory account of her life. Histories of our artists must be written honestly and sometimes even painfully – otherwise our civilisation will truly be wrecked.

Could it be magick? The occult returns to the art world

Andy Battaglia

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge and Tony Oursler have spent many years exploring paranormal phenomena through their artworks. Now, both have major exhibitions in New York – and suddenly they’re not alone in their interests

Fri 1 Jul 2016 modified on Tue 30 Apr 2019

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge and Tony Oursler have spent many years exploring paranormal phenomena through their artworks. Now, both have major exhibitions in New York – and suddenly they’re not alone in their interests

Fri 1 Jul 2016 modified on Tue 30 Apr 2019

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge: a pandrogenous devotee of sex magick. Photograph: Peter Dibdin/Publicity image

Drugs, blood, caskets, fish and hair all feature in the arsenal of supplies enlisted for art by Genesis Breyer P-Orridge. A few more, for variety’s sake: bones, a brass hand, dominatrix shoes and the discarded skin of a pet boa constrictor.

Best known as a musical dissident with the proto-industrial band Throbbing Gristle and later Psychic TV, Breyer P-Orridge has made visual art for decades as part of a ritualistic practice in which boundaries tend to blur. The first transmissions of musical noise started in the 1970s, but art has been part of the project from several years before then to the present day. Work of the more recent vintage makes up the bulk of Genesis Breyer P-Orridge: Try to Altar Everything, an exhibition on view at the Rubin Museum of Art in New York.

The Rubin museum focuses on correspondences between global contemporaneity and historic cultures from areas around the Himalayas and India, and the show surveys, in an expansive fashion, Breyer P-Orridge’s engagement with ideas from Hindu mythology and Nepal. Nepal is a favored haven away from the artist’s home in New York, but – as with most matters in Breyer P-Orridge’s realm – worldly matters turn otherworldly fast.

Reliquary by Genesis Breyer P-Orridge. Photograph: Invisible Exports