by University of California - San Diego

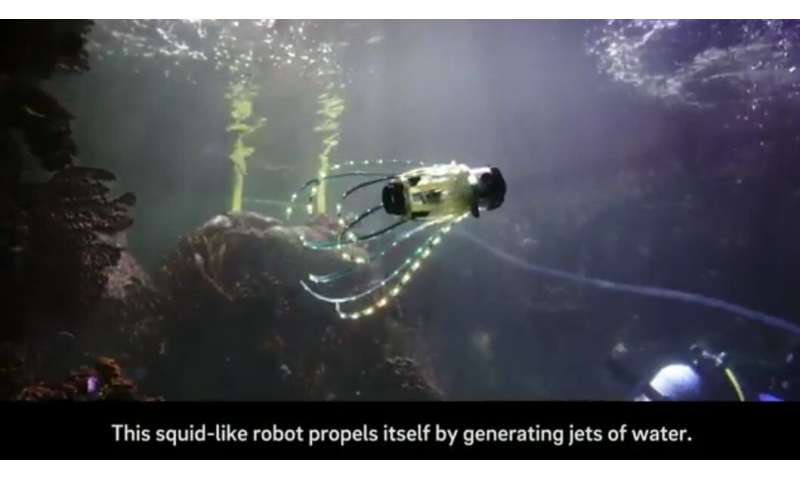

Engineers at the University of California San Diego have built a squid-like robot that can swim untethered, propelling itself by generating jets of water. The robot carries its own power source inside its body. It can also carry a sensor, such as a camera, for underwater exploration.

The researchers detail their work in a recent issue of Bioinspiration and Biomimetics.

"Essentially, we recreated all the key features that squids use for high-speed swimming," said Michael T. Tolley, one of the paper's senior authors and a professor in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at UC San Diego. "This is the first untethered robot that can generate jet pulses for rapid locomotion like the squid and can achieve these jet pulses by changing its body shape, which improves swimming efficiency."

This squid robot is made mostly from soft materials such as acrylic polymer, with a few rigid, 3-D printed and laser cut parts. Using soft robots in underwater exploration is important to protect fish and coral, which could be damaged by rigid robots. But soft robots tend to move slowly and have difficulty maneuvering.

The research team, which includes roboticists and experts in computer simulations as well as experimental fluid dynamics, turned to cephalopods as a good model to solve some of these issues. Squid, for example, can reach the fastest speeds of any aquatic invertebrates thanks to a jet propulsion mechanism.

VIDEO https://techxplore.com/news/2020-10-squidbot-jets-pics-coral-fish.htmlEngineers at the University of California San Diego have built a squid-like robot that can swim untethered, propelling itself by generating jets of water. The robot carries its own power source inside its body. It can also carry a sensor, such as a camera, for underwater exploration. Credit: University of California San Diego

Their robot takes a volume of water into its body while storing elastic energy in its skin and flexible ribs. It then releases this energy by compressing its body and generates a jet of water to propel itself.

At rest, the squid robot is shaped roughly like a paper lantern, and has flexible ribs, which act like springs, along its sides. The ribs are connected to two circular plates at each end of the robot. One of them is connected to a nozzle that both takes in water and ejects it when the robot's body contracts. The other plate can carry a water-proof camera or a different type of sensor.

Engineers first tested the robot in a water testbed in the lab of Professor Geno Pawlak, in the UC San Diego Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering. Then they took it out for a swim in one of the tanks at the UC San Diego Birch Aquarium at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

They demonstrated that the robot could steer by adjusting the direction of the nozzle. As with any underwater robot, waterproofing was a key concern for electrical components such as the battery and camera.They clocked the robot's speed at about 18 to 32 centimeters per second (roughly half a mile per hour), which is faster than most other soft robots.

"After we were able to optimize the design of the robot so that it would swim in a tank in the lab, it was especially exciting to see that the robot was able to successfully swim in a large aquarium among coral and fish, demonstrating its feasibility for real-world applications," said Caleb Christianson, who led the study as part of his Ph.D. work in Tolley's research group. He is now a senior medical devices engineering at San Diego-based Dexcom.

Researchers conducted several experiments to find the optimal size and shape for the nozzle that would propel the robot. This in turn helped them increase the robot's efficiency and its ability to maneuver and go faster. This was done mostly by simulating this kind of jet propulsion, work that was led by Professor Qiang Zhu and his team in the Department of Structural Engineering at UC San Diego. The team also learned more about how energy can be stored in the elastic component of the robot's body and skin, which is later released to generate a jet.

Explore further Transparent eel-like soft robot can swim silently underwater

More information: Caleb Michael Christianson et al, Cephalopod-inspired robot capable of cyclic jet propulsion through shape change, Bioinspiration & Biomimetics (2020). DOI: 10.1088/1748-3190/abbc72

Journal information: Bioinspiration and Biomimetics

Provided by University of California - San Diego