by Robert O'neill, Harvard University

Credit: Harvard University

Only a quarter of workers who were laid off or furloughed at the height of the pandemic lockdown actually received timely unemployment benefit, according to a survey by Shift Project researchers at Harvard Kennedy School and University of California, San Francisco. The systemic failure caused deep privation, including hunger and housing insecurity.

The new research is based on a survey conducted in April and May of 2,500 workers who lost their jobs from 110 of the largest service sector companies in the United States—companies in the retail, food service, hospitality, grocery, pharmacy, fulfillment, or hardware sectors. The survey also found enormous variation between states, ranging from 77% of unemployed workers who applied for unemployment insurance (UI) receiving unemployment benefits in Minnesota to just 8% in Florida.

The report comes as Congress struggles to approve a new economic rescue package for the country, including the extension of unemployment benefits for affected workers.

"Recent debates over the appropriate amount of unemployment insurance benefits often assume that unemployed workers will actually receive these benefits," said Daniel Schneider, professor of public policy at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), professor of sociology at Harvard, and co-principal investigator of the Shift Project. "Our research shows that was far from the case, and the consequences were catastrophic for working families."

"Our research shows that it doesn't have to be this way," said Kristen Harknett, associate professor at the University of California, San Francisco, and the Shift Project's co-principal investigator. "Although unemployed workers faced delays and barriers in the UI process in some states, states like Minnesota and Massachusetts got UI benefits into the hands of workers who needed them in a timely fashion. And these benefits made a huge difference in keeping workers afloat."

Prior to the pandemic, the report notes, workers already faced hurdles when applying for unemployment insurance: They needed to document their job searches meticulously, faced long response times, and were also frustrated by technical glitches on state websites. The coronavirus pandemic, and the ensuing lockdown and economic crisis, exacerbated these inefficiencies.

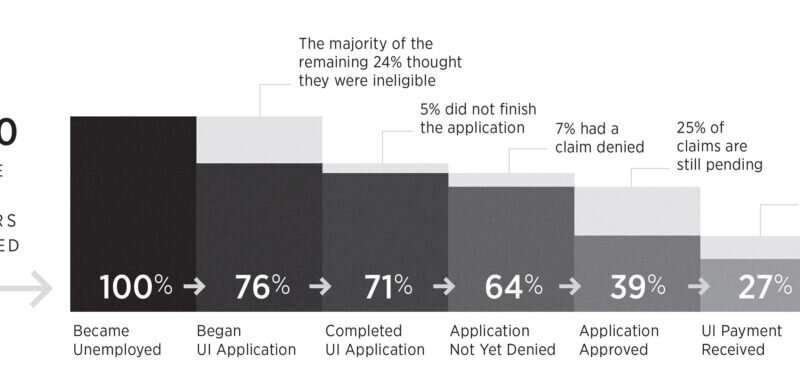

The report found those seeking unemployment insurance benefits faced many barriers along the way. Only 76% applied for unemployment insurance in the first place, with most of those who failed to make a claim saying they did not believe they were eligible. Another 5% of the total fell off along the application process, leaving only 71% with completed applications. Of the remaining 39% who had not been rejected or had not yet heard back regarding their claim, just 27% had actually received benefits.

"Although the share of unemployed workers receiving UI benefits may increase over time," the researchers write, "our data suggest that workers experience a sizable period of time without benefits. Even among those who had been unemployed for two months or more, only 25% had received a UI payment."

The absence of unemployment benefits brought real hardships. Researchers found that 26% of unemployed workers who had not yet received their benefits experienced hunger in the prior month. But, for unemployed workers who received UI, they were no worse-off than those who were still employed. (The researchers point out though that food insecurity remains a chronic condition even for those with service-sector jobs—13% of both employed workers and workers who received UI experienced hunger in the prior month.)

Additionally, 13% faced housing insecurity—doubling up for housing or staying in a shelter or other place not meant for housing. And nearly one in five, 18%, reported that someone in their household didn't get medical care they needed because of the cost.

There were stark differences in how the unemployed fared across the country. The unemployed fared better in Minnesota (where 77% received benefits), Massachusetts (65%) and Virginia (64%). About half of applicants in California, Missouri, North Carolina, New York, and Tennessee had received their unemployment benefits. Rates of receipt were much lower in Colorado (25%), Illinois (24%), Indiana (27%), and Ohio (24%). Florida stands alone at the bottom of the list, with just 8% of applicants having received their unemployment benefits.

The Shift Project, now based at the Kennedy School's Malcolm Weiner Center for Social Policy, was started by Schneider and Harknett in 2016 to study the economic uncertainty faced by service sector workers in the San Francisco Bay Area. It has grown into the largest source of data on work scheduling for hourly service workers in the retail and fast-food sectors from across the country. Schneider joined HKS from the University of California, Berkeley, in July.

Explore furtherAmerica's least educated and lowest paid remain hardest hit by pandemic

Only a quarter of workers who were laid off or furloughed at the height of the pandemic lockdown actually received timely unemployment benefit, according to a survey by Shift Project researchers at Harvard Kennedy School and University of California, San Francisco. The systemic failure caused deep privation, including hunger and housing insecurity.

The new research is based on a survey conducted in April and May of 2,500 workers who lost their jobs from 110 of the largest service sector companies in the United States—companies in the retail, food service, hospitality, grocery, pharmacy, fulfillment, or hardware sectors. The survey also found enormous variation between states, ranging from 77% of unemployed workers who applied for unemployment insurance (UI) receiving unemployment benefits in Minnesota to just 8% in Florida.

The report comes as Congress struggles to approve a new economic rescue package for the country, including the extension of unemployment benefits for affected workers.

"Recent debates over the appropriate amount of unemployment insurance benefits often assume that unemployed workers will actually receive these benefits," said Daniel Schneider, professor of public policy at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), professor of sociology at Harvard, and co-principal investigator of the Shift Project. "Our research shows that was far from the case, and the consequences were catastrophic for working families."

"Our research shows that it doesn't have to be this way," said Kristen Harknett, associate professor at the University of California, San Francisco, and the Shift Project's co-principal investigator. "Although unemployed workers faced delays and barriers in the UI process in some states, states like Minnesota and Massachusetts got UI benefits into the hands of workers who needed them in a timely fashion. And these benefits made a huge difference in keeping workers afloat."

Prior to the pandemic, the report notes, workers already faced hurdles when applying for unemployment insurance: They needed to document their job searches meticulously, faced long response times, and were also frustrated by technical glitches on state websites. The coronavirus pandemic, and the ensuing lockdown and economic crisis, exacerbated these inefficiencies.

The report found those seeking unemployment insurance benefits faced many barriers along the way. Only 76% applied for unemployment insurance in the first place, with most of those who failed to make a claim saying they did not believe they were eligible. Another 5% of the total fell off along the application process, leaving only 71% with completed applications. Of the remaining 39% who had not been rejected or had not yet heard back regarding their claim, just 27% had actually received benefits.

"Although the share of unemployed workers receiving UI benefits may increase over time," the researchers write, "our data suggest that workers experience a sizable period of time without benefits. Even among those who had been unemployed for two months or more, only 25% had received a UI payment."

The absence of unemployment benefits brought real hardships. Researchers found that 26% of unemployed workers who had not yet received their benefits experienced hunger in the prior month. But, for unemployed workers who received UI, they were no worse-off than those who were still employed. (The researchers point out though that food insecurity remains a chronic condition even for those with service-sector jobs—13% of both employed workers and workers who received UI experienced hunger in the prior month.)

Additionally, 13% faced housing insecurity—doubling up for housing or staying in a shelter or other place not meant for housing. And nearly one in five, 18%, reported that someone in their household didn't get medical care they needed because of the cost.

There were stark differences in how the unemployed fared across the country. The unemployed fared better in Minnesota (where 77% received benefits), Massachusetts (65%) and Virginia (64%). About half of applicants in California, Missouri, North Carolina, New York, and Tennessee had received their unemployment benefits. Rates of receipt were much lower in Colorado (25%), Illinois (24%), Indiana (27%), and Ohio (24%). Florida stands alone at the bottom of the list, with just 8% of applicants having received their unemployment benefits.

The Shift Project, now based at the Kennedy School's Malcolm Weiner Center for Social Policy, was started by Schneider and Harknett in 2016 to study the economic uncertainty faced by service sector workers in the San Francisco Bay Area. It has grown into the largest source of data on work scheduling for hourly service workers in the retail and fast-food sectors from across the country. Schneider joined HKS from the University of California, Berkeley, in July.

Explore furtherAmerica's least educated and lowest paid remain hardest hit by pandemic

Provided by Harvard University

This story is published courtesy of the Harvard Gazette, Harvard University's official newspaper. For additional university news, visit Harvard.edu.

This story is published courtesy of the Harvard Gazette, Harvard University's official newspaper. For additional university news, visit Harvard.edu.

No comments:

Post a Comment