Typhoid-causing bacteria have become more resistant to essential antibiotics, spreading widely over past 30 years

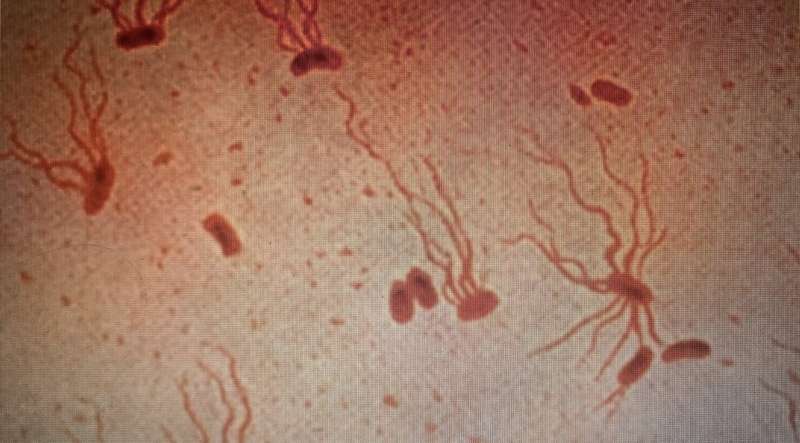

Bacteria causing typhoid fever are becoming increasingly resistant to some of the most important antibiotics for human health, according to a study published in The Lancet Microbe journal. The largest genome analysis of Salmonella enterica serovar typhi (S. typhi) also reveals that resistant strains—almost all originating in South Asia—have spread to other countries nearly 200 times since 1990.

Typhoid fever is a global public health concern, causing 11 million infections and more than 100,000 deaths per year. While it is most prevalent in South Asia—which accounts for 70% of the global disease burden—it also has significant impacts in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and Oceania, highlighting the need for a global response.

Antibiotics can be used to successfully treat typhoid fever infections, but their effectiveness is threatened by the emergence of resistant S. typhi strains. Analysis of the rise and spread of resistant S. typhi has so far been limited, with most studies based on small samples.

The authors of the new study performed whole-genome sequencing on 3,489 S. typhi isolates obtained from blood samples collected between 2014 and 2019 from people in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Pakistan with confirmed cases of typhoid fever. A collection of 4,169 S. typhi samples isolated from more than 70 countries between 1905 and 2018 was also sequenced and included in the analysis.

Resistance-conferring genes in the 7,658 sequenced genomes were identified using genetic databases. Strains were classified as multidrug-resistant (MDR) if they contained genes giving resistance to classical front-line antibiotics ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. The authors also traced the presence of genes conferring resistance to macrolides and quinolones, which are among the most critically important antibiotics for human health.

The analysis shows resistant S. typhi strains have spread between countries at least 197 times since 1990. While these strains most often occurred within South Asia and from South Asia to Southeast Asia, East and Southern Africa, they have also been reported in the UK, U.S., and Canada.

Since 2000, MDR S. typhi has declined steadily in Bangladesh and India, and remained low in Nepal (less than 5% of typhoid strains), though it has increased slightly in Pakistan. However, these are being replaced by strains resistant to other antibiotics.

For example, gene mutations giving resistance to quinolones have arisen and spread at least 94 times since 1990, with nearly all of these (97%) originating in South Asia. Quinolone-resistant strains accounted for more than 85% of S. typhi in Bangladesh by the early 2000s, increasing to more than 95% in India, Pakistan, and Nepal by 2010. Mutations causing resistance to azithromycin—a widely used macrolide antibiotic—have emerged at least seven times in the past 20 years. In Bangladesh, strains containing these mutations emerged around 2013, and since then their population size has steadily increased. The findings add to recent evidence of the rapid rise and spread of S. typhi strains resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, another class of antibiotics critically important for human health.

Lead author Dr. Jason Andrews of Stanford University (U.S.) says, "The speed at which highly-resistant strains of S. typhi have emerged and spread in recent years is a real cause for concern, and highlights the need to urgently expand prevention measures, particularly in countries at greatest risk. At the same time, the fact resistant strains of S. typhi have spread internationally so many times also underscores the need to view typhoid control, and antibiotic resistance more generally, as a global rather than local problem."

The authors acknowledge some limitations to their study. There remains an underrepresentation of S. typhi sequences from several regions, particularly many countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Oceania, where typhoid is endemic. More sequences from these regions are needed to improve understanding of timing and patterns of spread. Even in countries with better sampling, most isolates come from a small number of surveillance sites and may not be representative of the distribution of circulating strains. As S. typhi genomes only cover a fraction of all typhoid fever cases, estimates of resistance-causing mutations and international spread are likely underestimated. These potential underestimates highlight the need to expand genomic surveillance to provide a more comprehensive window into the emergence, expansion, and spread of antibiotic-resistant organisms.Tracing travelers' typhoid to get an early warning of emerging threats

No comments:

Post a Comment