ByBrent M. Eastwood

Published 2 days ago

SR-71 spy plane. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

The SR-71 Blackbird: The Fastest Plane, the Most Repairs Needed?: It was a mystery. The SR-71 Blackbird was built of titanium and other space-age alloys to handle the excessive heat caused by high-altitude and high-speed flight. But for some reason, some of the titanium parts were corroding. Various elements showed corrosion in the summer, but no problems were found during the winter months. This was just one of many odd problems found on the SR-71, still the fastest plane ever to fly. And, even stranger, it sits retired in a museum. Here are just a few of the issues the Blackbird encountered during its career:

How Did The Engineers Figure Out the Corrosion Problem?

Thankfully the engineers worked like present-day data scientists. They had evidence from the titanium scraps that were discarded during the production process. Engineers had kept track of each scrap and described its condition in a database. They then devised a trend analysis and found something that shed some insights into the problem.

Summer Versus Winter – a Whodunit

Parts welded in the summer were failing soon after work was completed. But in the winter no such issues were found. What was causing this conundrum? Engineers knew that in the summer, water was used to clean parts to prevent algae build-up on the titanium.

They found that the culprit was chlorine in the water and that affected the titanium negatively. They started using distilled water and that helped.

A NEW ISSUE CROPPED UP

Linda Sheffield Miller of the Aviation Geek Club who recounted the water problem also found another issue that SR-71 engineers had to solve.

“They discovered that their cadmium plated tools were leaving trace amounts of cadmium on bolts, which would cause galvanic corrosion and cause the bolts to fail. This discovery led to all cadmium tools to be removed from the workshop.”

THE NEXT SR-71 PROBLEM: KEEP THE TIRES FROM MELTING?

Another issue had to do with the tires. They could melt at Mach 3.3 and 600, maybe even up to a 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit. Workers used aluminum on the areas where the wheels retracted and added latex. Then they filled the tires with nitrogen.

The tire pressure was 415 pounds per square inch compared to the 35 psi in your car.

STABILIZE THE FUEL

What about the fuel at high temperatures? For every hour of flight, the Blackbird needed at least 18 tons of fuel. Shell Oil created a low volatility tailor-made fuel called JP-7 that could withstand the rigors of flight and not evaporate at high altitude (up to 85,000 feet). They added a chemical element called cesium to help stabilize the fuel so it would have a higher flashpoint. The cesium also helped reduce the radar signatures from the jet exhaust plume.

RADAR EVASION HAD TO BE IMPROVED

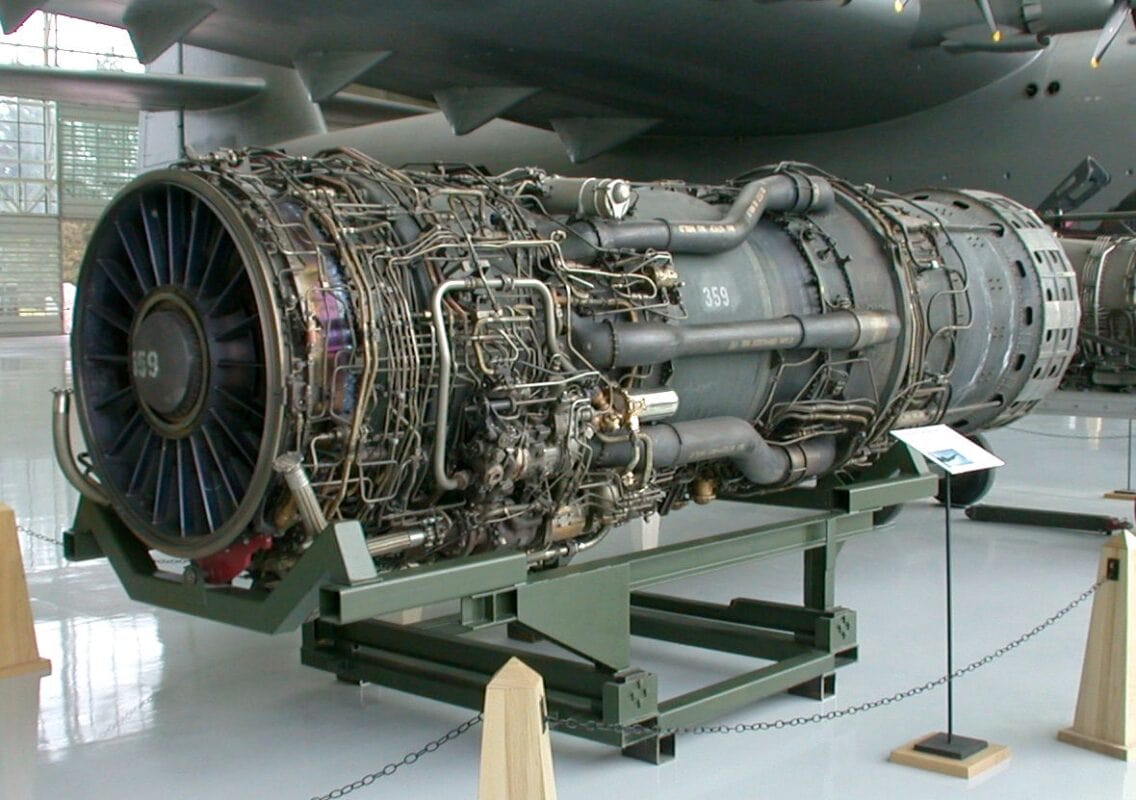

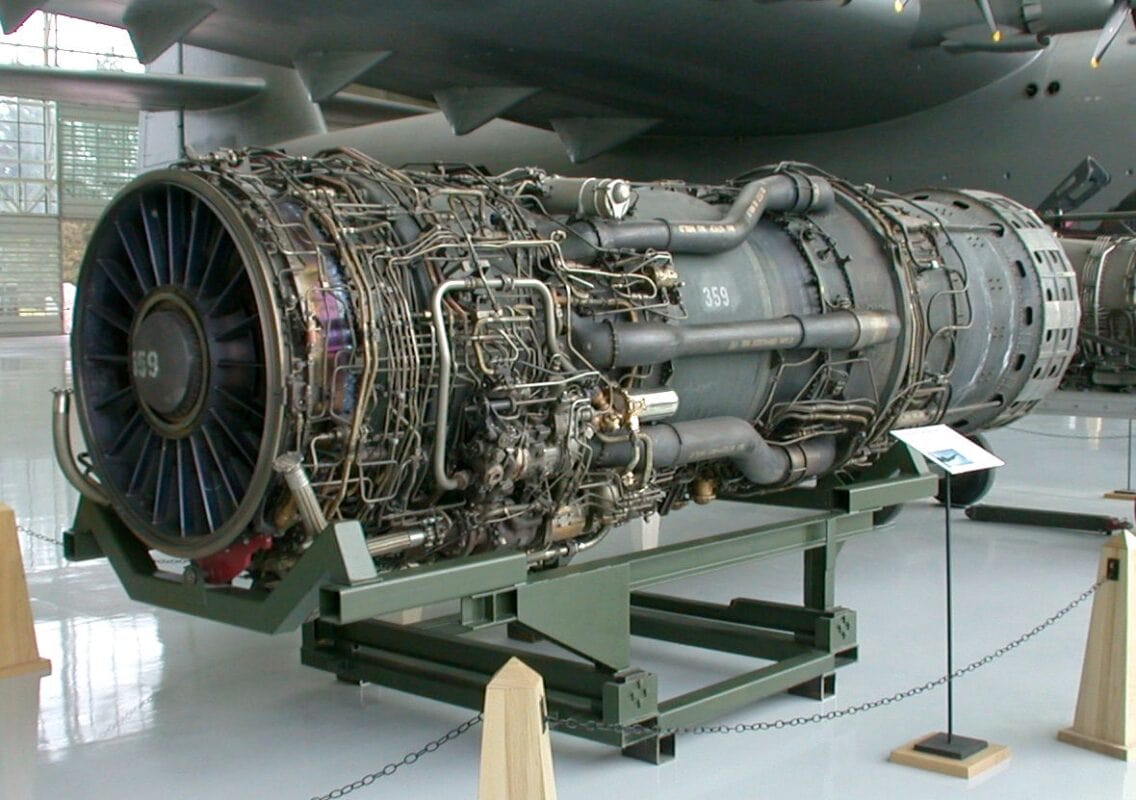

To better evade radar, the Pratt and Whitney J58 engines had pointed cones to protect the face of the inlets. The extensions on the front edge of the wings were curved. The rear vertical stabilizers were angled. Special “iron paint” made of iron ferrite particles was used to reduce radar signature. This coating would have a high price tag at $400 per quart

A direct front view of an SR-71 Blackbird aircraft after

WRITTEN BYBrent M. Eastwood

The SR-71 Blackbird: The Fastest Plane, the Most Repairs Needed?: It was a mystery. The SR-71 Blackbird was built of titanium and other space-age alloys to handle the excessive heat caused by high-altitude and high-speed flight. But for some reason, some of the titanium parts were corroding. Various elements showed corrosion in the summer, but no problems were found during the winter months. This was just one of many odd problems found on the SR-71, still the fastest plane ever to fly. And, even stranger, it sits retired in a museum. Here are just a few of the issues the Blackbird encountered during its career:

How Did The Engineers Figure Out the Corrosion Problem?

Thankfully the engineers worked like present-day data scientists. They had evidence from the titanium scraps that were discarded during the production process. Engineers had kept track of each scrap and described its condition in a database. They then devised a trend analysis and found something that shed some insights into the problem.

Summer Versus Winter – a Whodunit

Parts welded in the summer were failing soon after work was completed. But in the winter no such issues were found. What was causing this conundrum? Engineers knew that in the summer, water was used to clean parts to prevent algae build-up on the titanium.

They found that the culprit was chlorine in the water and that affected the titanium negatively. They started using distilled water and that helped.

A NEW ISSUE CROPPED UP

Linda Sheffield Miller of the Aviation Geek Club who recounted the water problem also found another issue that SR-71 engineers had to solve.

“They discovered that their cadmium plated tools were leaving trace amounts of cadmium on bolts, which would cause galvanic corrosion and cause the bolts to fail. This discovery led to all cadmium tools to be removed from the workshop.”

THE NEXT SR-71 PROBLEM: KEEP THE TIRES FROM MELTING?

Another issue had to do with the tires. They could melt at Mach 3.3 and 600, maybe even up to a 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit. Workers used aluminum on the areas where the wheels retracted and added latex. Then they filled the tires with nitrogen.

The tire pressure was 415 pounds per square inch compared to the 35 psi in your car.

STABILIZE THE FUEL

What about the fuel at high temperatures? For every hour of flight, the Blackbird needed at least 18 tons of fuel. Shell Oil created a low volatility tailor-made fuel called JP-7 that could withstand the rigors of flight and not evaporate at high altitude (up to 85,000 feet). They added a chemical element called cesium to help stabilize the fuel so it would have a higher flashpoint. The cesium also helped reduce the radar signatures from the jet exhaust plume.

RADAR EVASION HAD TO BE IMPROVED

To better evade radar, the Pratt and Whitney J58 engines had pointed cones to protect the face of the inlets. The extensions on the front edge of the wings were curved. The rear vertical stabilizers were angled. Special “iron paint” made of iron ferrite particles was used to reduce radar signature. This coating would have a high price tag at $400 per quart

A direct front view of an SR-71 Blackbird aircraft after

landing from its 1,000th sortie.

SR-71 and F-16. Image: Creative Commons.

SR-71 Engine from Pratt & Whitney J58

The SR-71 Took a Ton of Maintenance

Being the fastest plane on Earth did not come easy, and maintenance was key, even if it took a lot of maintenance to keep the SR-71 flying high.

Workers had to work long hours to keep the Blackbird in the air. As you could imagine, one flight could result in missing parts that needed to be repaired. 12 of 34 airplanes produced were lost due to accidents involving various mechanical failures. Each flight was an adventure for ground crews. Airplane historian Jenny Ma described it well.

“The teams compared each takeoff to a rocket launch — if there’s a mission now, the Blackbird will be off the ground in 19 hours. To just start the plane, a “start cart’ is needed to connect to each engine and help them get to the minimum 3000 RPM for it to become self-sustaining.”

SR-71. SR-71 photo taken at the National Air and Space Museum.

SR-71 and F-16. Image: Creative Commons.

SR-71 Engine from Pratt & Whitney J58

The SR-71 Took a Ton of Maintenance

Being the fastest plane on Earth did not come easy, and maintenance was key, even if it took a lot of maintenance to keep the SR-71 flying high.

Workers had to work long hours to keep the Blackbird in the air. As you could imagine, one flight could result in missing parts that needed to be repaired. 12 of 34 airplanes produced were lost due to accidents involving various mechanical failures. Each flight was an adventure for ground crews. Airplane historian Jenny Ma described it well.

“The teams compared each takeoff to a rocket launch — if there’s a mission now, the Blackbird will be off the ground in 19 hours. To just start the plane, a “start cart’ is needed to connect to each engine and help them get to the minimum 3000 RPM for it to become self-sustaining.”

SR-71. SR-71 photo taken at the National Air and Space Museum.

Taken by 19FortyFive on 10/1/2022.

SR-71

SR-71 photo taken at the National Air and Space Museum.

SR-71

SR-71 photo taken at the National Air and Space Museum.

Taken by 19FortyFive on 10/1/2022.

SR-71 Blackbird 19FortyFive Original Image. Taken 10/1/2022.

SR-71 Blackbird, Udvar-Hazy Center | National Air and Space Museum.

SR-71 Blackbird 19FortyFive Original Image. Taken 10/1/2022.

SR-71 Blackbird, Udvar-Hazy Center | National Air and Space Museum.

October 1, 2022. 19FortyFive Original Image.

Today’s airplane engineers and designers could learn many lessons from the SR-71. It was so far ahead of its time that it paved the way for new stealth bombers and fighters. The personnel involved were able to keep the details of the airplane secret, but perhaps that would not be possible today with civilian flight enthusiasts taking and distributing photos of new airplanes on social media.

One thing is certain, the SR-71 Blackbird was a stunning feat of American ingenuity, no matter how much repair and maintenance was needed.

Today’s airplane engineers and designers could learn many lessons from the SR-71. It was so far ahead of its time that it paved the way for new stealth bombers and fighters. The personnel involved were able to keep the details of the airplane secret, but perhaps that would not be possible today with civilian flight enthusiasts taking and distributing photos of new airplanes on social media.

One thing is certain, the SR-71 Blackbird was a stunning feat of American ingenuity, no matter how much repair and maintenance was needed.

WRITTEN BYBrent M. Eastwood

Now serving as 1945’s Defense and National Security Editor, Brent M. Eastwood, PhD, is the author of Humans, Machines, and Data: Future Trends in Warfare. He is an Emerging Threats expert and former U.S. Army Infantry officer. You can follow him on Twitter @BMEastwood.

No comments:

Post a Comment