Are Small Modular Reactors The Future Of Nuclear Power?

- Nuclear power is falling back in favor as the push to slash emissions accelerates.

- Small modular nuclear reactors are affordable and convenient alternatives to traditional plants.

- Scores of governments, including the U.S. government, have begun incentivizing SMRs by making them more attractive for lenders and utilities.

For decades, many countries have maintained a love-hate relationship with nuclear energy, with the sector regarded as the black sheep of the alternative energy industry thanks to poor public perception, a series of high-profile disasters such as Chernobyl, Fukushima and Three Miles Island as well as massive cost-overruns by nuclear projects. Currently, 440 nuclear reactors operate globally, providing ~10% of the world’s electricity, down from 15 percent at nuclear power’s peak in 1996. In the United States, 93 nuclear reactors generate ~20 percent of the country’s electricity supply.

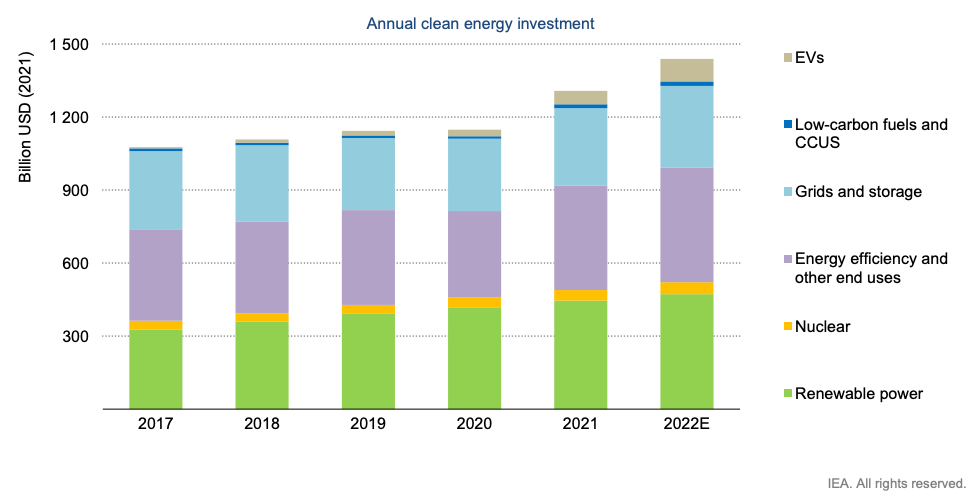

But Russia’s war in Ukraine and the need for energy security are now forcing a major realignment of energy systems on a global scale, with countries that were formerly strongly opposed to nuclear power such as Germany and Japan now seriously considering incorporating more nuclear energy in their energy mix. Further, the global energy transition is in full swing, and many experts are coming to the realization that the world needs more nuclear power to meet our climate goals. Indeed, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the world needs to double the annual rate of nuclear capacity additions in order to reach the 2050 net-zero target. Further, nuclear plants can be paired up with renewable energy projects to act as baseload power thanks to nuclear power possessing the highest capacity factor of any energy source: nuclear plants produce at maximum power more than 93 percent of the time compared to 57 percent for natural gas and 25 percent for solar energy.

Unfortunately, it’s going to be incredibly hard to achieve that milestone thanks to the harsh reality of nuclear power projects. Consider that it not only takes an average of eight years to build a nuclear power plant, but also the mean time between the decision and the commissioning typically ranges from 10 to 19 years. Additionally, major commercial hurdles, primarily the large upfront capital cost and huge cost overruns (nuclear plants have the greatest frequency of cost overruns of all utility-scale power projects), make this an even more onerous endeavor.

Enter small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs).

SMRs are advanced nuclear reactors with power capacities that range from 50-300 MW(e) per unit, compared to 700+ MW(e) per unit for traditional nuclear power reactors. Their biggest attributes are:

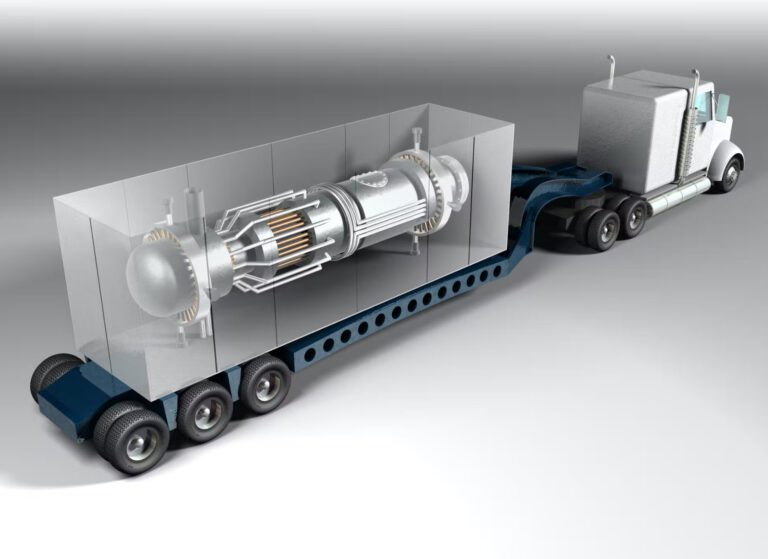

- Modular – this makes it possible for SMR systems and components to be factory-assembled and transported as a unit to a location for installation.

- Small – SMRs are physically a fraction of the size of a conventional nuclear power reactor.

Given their smaller footprint, SMRs can be sited on locations not suitable for larger nuclear power plants, such as retired coal plants. Prefabricated SMR units can be manufactured, shipped and then installed on site, making them more affordable to build than large power reactors. Additionally, SMRs offer significant savings in cost and construction time, and can also be deployed incrementally to match increasing power demand. Another key advantage: SMRs have reduced fuel requirements, and can be refueled every 3 to 7 years compared to between 1 and 2 years for conventional nuclear plants. Indeed, some SMRs are designed to operate for up to 30 years without refueling.

Source: International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)

Source: Geopolitical Intelligence Services AG

Encouraging SMR Development

Scores of governments, including the U.S. government, have begun incentivizing SMRs by making them more attractive for lenders and utilities.

“You simply must have some form of reliable, baseload power because you can’t get there with assets that operate (part of) the time. A nuclear power plant is more costly upfront, but it is an asset that operates for 80 years. If you compare that to wind and solar, they generally have 20-year lifetimes and batteries of around eight years. If you compare renewables and batteries to nuclear, nuclear stacks up very, very well,” Jeff Merrifield, partner, Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman, and a former Nuclear Regulatory Commissioner, said during a recent nuclear energy virtual press conference hosted by the United States Energy Association. Merrifield pointed to West Virginia, Idaho, Wyoming, as some of the states where SMRs would be suitable, noting that they all lack nuclear plants but have enacted legislation that allows small modular reactors to develop.

Back in 2020, the U.S. Department of Commerce launched a Small Modular Reactor Working Group that looks to expedite SMR deployment in European markets in a bid to position U.S. companies to succeed in those markets. Meanwhile, Ghana and Kenya are also looking to develop SMRs to expand their power generation capacities.

But the private sector is just as active in the SMR arena.

TerraPower and GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy launched the Natrium project in 2020 to design SMRs that they hope to commercialize by 2030. The partners are currently testing the technology, along with Berkshire Hathaway’s PacifiCorp. The Natrium reactors are intended to act as power backup for wind and solar projects.

NuScale, a subsidiary of American multinational engineering and construction firm Fluor, has lined up plans to start building SMRs in Idaho starting 2026. The company’s designs will combine 12 modules to generate 924-megawatts, equivalent to the output of a large nuclear plant.

And now the million dollar question: are SMRs the future of nuclear power?

You will notice that a major SMR wave hit around 2020 at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic but well before Russia invaded Ukraine. It’s therefore possible that the ongoing global energy crisis, climate concerns and the much smaller footprint by SMRs compared to traditional reactors will persuade the public that this is the way to go.

However, studies like these that paint SMRs in a bad light have the potential to throw a spanner in the works and increase public resistance if proven to be accurate:

“Our results show that most small modular reactor designs will actually increase the volume of nuclear waste in need of management and disposal, by factors of 2 to 30 for the reactors in our case study. These findings stand in sharp contrast to the cost and waste reduction benefits that advocates have claimed for advanced nuclear technologies,” said study lead author Lindsay Krall, a former MacArthur Postdoctoral Fellow at Stanford University’s Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC). The study found that one of their key attractions--small size--is also their major Achilles heel because SMRs experience more neutron leakage than conventional reactors, which in turn affects the amount and composition of their waste streams. The study also discovered that spent nuclear fuel from SMRs will be discharged in greater volumes per unit energy produced and can be far more complex compared to waste from conventional reactors.

By Alex Kimani for Oilprice.com

These “microreactors” could be the future of nuclear power

They’re being explored for use everywhere from disaster zones to moon bases.

Credit: US Department of Energy

By Kristin Houser

February 18, 2023

This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Thursday morning by subscribing here.

One of the best ways to scale up the use of clean nuclear energy in the future might be to scale down the tech, with “microreactors” that can be built and deployed in a fraction of the time required for traditional nuclear power plants. They’re being explored for use everywhere from university campuses to disaster zones and even bases on the moon.

The nuclear option

At nuclear power plants, atoms are split inside reactors. This process — nuclear fission — releases a tremendous amount of energy in the form of heat. That heat is then used to boil water, creating steam that spins electricity-generating turbines.

Unlike the burning of coal or natural gas, nuclear fission doesn’t generate carbon emissions. It’s also more consistent than environmentally dependent sources of energy, such as solar and wind power, while taking up much less physical space than solar or wind farms.

Despite those benefits, only 10% of the world’s electricity is generated by nuclear power plants, and the power source is on the decline, with older plants closing faster than new ones are being built — and size is a major reason for this downturn.

“The biggest barrier to new nuclear construction is mobilising investment.”INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY

Matters of size

Most nuclear power plants are massive affairs — in the US, the average facility takes up about a square mile of land and generates 1 gigawatt (GW) of power, which is about enough to power 750,000 homes.

Building such a plant today can cost upwards of $10 billion and take 7 years, and that’s if everything goes according to plan.

In Georgia, a project to add two 1.1 GW reactors to an existing nuclear power plant started construction in 2009 with an estimated cost of $14 billion — the total cost of the project now exceeds $30 billion, and construction still isn’t complete.

Rather than take on such a risky endeavor, clean energy investors are more likely to put their money into solar or wind farms, which are cheaper but require 75 and 360 times as much land, respectively, to generate the same amount of power as the steady 1 GW nuclear reactor.

“The biggest barrier to new nuclear construction is mobilising investment,” wrote the International Energy Agency in a 2019 report.

Microreactors

Rather than hoping investors will take a chance on building large nuclear power plants like the ones we already have, some experts are betting on “microreactors” as the future of nuclear energy.

These in-development reactors are a 100th to 1,000th the size of traditional ones, and while they couldn’t meet the energy needs of a large city, they can be deployed in more places and could potentially power a small remote community, a military base, or even a college campus.

Because microreactors are designed to be built and assembled in factories and then shipped to a site for installation, their upfront cost is expected to be much lower. They can also be deployed quickly, which opens up their potential use in disaster relief.

“Having another option for restoring power quickly following natural disasters would support faster restoration of critical services such as hospitals, communications, and the water supply to the local community,” wrote the US Government Accountability Office in 2020.

Looking ahead

Microreactors are still a new technology, and the US’s Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) has yet to approve a design for commercial use.

The NRC did recently approve its first small modular reactor — those are factory-made reactors larger than microreactors, but still far smaller than traditional designs — and microreactors could be next, as several groups plan to demonstrate their tech within the next five years or so.

Here are a few projects to keep your eye on:

Project Pele: In April 2022, the US Department of Defense announced that it was moving forward with Project Pele, an initiative to design, build, and demonstrate a prototype microreactor at the Idaho National Laboratory (INL).

This reactor will be in the range of 1-5 MW and is being built by nuclear energy company BWX Technologies as part of a $300 million contract. BWXT is expected to deliver the microreactor to the INL in 2024, and the plan is for it to be operational within 72 hours of delivery.

INL will then run the microreactor for at least three years at full capacity. The US already envisions applying what it learns from the prototype to future military efforts, as well as space missions that will require us to provide power to astronauts on the moon.

Microreactors could be built and then shipped via truck, train, or plane. Credit: INL

Westinghouse’s eVinci: Pennsylvania’s Westinghouse Electric Company — a pioneer of nuclear power back in the 1950s, and the same company working on the expensive nuclear power project in Georgia — is developing its own microreactor: the eVinci.

This microreactor is designed to generate up to 5 MW of electricity or 13 MW of heat — essentially, rather than using the heat from fission to boil water, it can be used directly to warm homes and other buildings.

The eVinci is designed to take less than 30 days to install onsite, and while the first units are expected to cost $90 million to $120 million, Westinghouse believes the price could drop to about $60 million as production increases.

The company has already begun submitting documents needed for approval to the NRC. It hopes to have its tech licensed by 2027, and Penn State has already signed a memorandum of understanding with the company to install an eVinci on its main campus.

Radiant’s Kaleidos: In 2020, a team of former SpaceX engineers launched Radiant, a startup focused on the development of a 1.2 MW nuclear microreactor, called “Kaleidos,” that is designed to fit inside a shipping container and be installed overnight.

Radiant envisions Kaleidos replacing the diesel generators used by remote communities. The microreactor could also be installed at hospitals, data centers, and military bases to provide backup power in the event the main source of electricity fails.

Radiant hopes to have a fueled demonstration of the reactor ready by 2026, and while it hasn’t said what Kaleidos will cost, it says it expects it to be cheaper than diesel generators. For now, it will continue developing the system with researchers at the DoE’s Argonne National Laboratory.

“We plan to be the first new commercial reactor design to achieve a fueled test in more than 50 years,” said Radiant CEO Doug Bernauer.

The bottom line

While many microreactor designs are expected to be safer than full-sized plants, they still produce a small amount of radioactive waste that needs to be stored. Many also require high-assay low-enriched uranium, which is easier (although not easy) to make into nuclear weapons than the less enriched fuel used in traditional reactors.

Besides those limitations, it would also take a lot of microreactors to decarbonize the world — but that doesn’t mean the tech couldn’t be a key piece of the clean energy puzzle, along with its larger counterpart, the small modular reactor.

“While the role of large reactors continues to be important to our nation and others around the world, customers needs [sic] product choice and that is precisely what these smaller systems provide,” writes the DoE.

First small modular nuclear reactor certified in US

A single nuclear power plant could host up to 12 of these reactors.

Credit: NuScale

By Kristin Houser

January 25, 2023

The US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) has certified the design of a small modular reactor for the first time — potentially opening the door to cheaper, safer nuclear power plants.

Nuclear power: When atoms are split, they release a tremendous amount of energy in the form of heat. Nuclear power plants trigger that process in reactors, and then use the heat to boil water, creating steam that spins electricity-generating turbines.

Nuclear power plants don’t generate greenhouse gas emissions, making them a cleaner source of electricity than coal or natural gas, and they’re more consistent than solar or wind farms while also taking up less space.

The challenge: Despite these benefits, nuclear power is on the decline in the US, with old plants shutting down faster than new ones are being built.

Small modular reactors may be a way to reinvigorate the nuclear power industry.

Cost is a major reason for this decline. Owners of aging plants are opting to shutter them rather than pay for costly repairs, and few want to commit to building brand new reactors with the designs we have, as that can cost upwards of $10 billion and take 7 years.

Add in the falling cost of renewables and a public that can be wary of nuclear power due to safety concerns, and the idea of getting into the nuclear business seems even less appealing.

What’s new? Dozens of companies see small modular reactors as a way to reinvigorate the industry.

Unlike reactors in nuclear plants today, which are all unique designs built on site, these reactors would be standardized and built on an assembly line. The small reactors could then be shipped to a site, cutting the cost and time needed to establish a new nuclear power plant.

“Small modular reactors are no longer an abstract concept.”KATHRYN HUFF

Now that the NRC has certified its first small modular reactor design — developed by Oregon-based energy company NuScale — we’ll finally get a chance to see if they live up to their promise in the US.

“SMRs are no longer an abstract concept,” said Assistant Secretary for Nuclear Energy Kathryn Huff. “They are real, and they are ready for deployment thanks to the hard work of NuScale, the university community, our national labs, industry partners, and the NRC.”

The tech: At just 76 feet tall, NuScale’s reactor is about one-third the size of other certified reactor designs. It can generate 50 megawatts of electricity — that’s only about 5% as much as a traditional reactor, but a single plant could host up to 12 reactors, according to NuScale.

NuScale’s small modular reactor also has a passive cooling system, designed to prevent the reactor from melting down even if the cooling system loses power, which could help alleviate safety concerns.

Looking ahead: Now that the NRC has certified the design of NuScale’s small modular reactor, anyone interested in building a new plant powered by the tech can apply for a license to use it.

It might not be long before we see these reactors up and running, either — NuScale says it has signed 19 agreements with groups in the US and internationally to deploy the reactors.

Smaller, safer, cheaper? Modular nuclear plants could reshape coal country

The Biden administration envisions dozens of ‘modular’ nuclear plants sprouting across the country. Why coal communities are so eager to be the staging ground for the risky endeavor.

By Evan Halper

February 19, 2023

WISE, Va. — As Michael Hatfield scanned the landscape from atop the abandoned mine where he once worked, he saw more than a patch of Appalachia left behind by an energy economy in transition. He saw a launchpad for the next nuclear age.

The nuclear power plants Hatfield has in mind are not what you think. No massive cooling towers, miles of concrete, expansive evacuation zones. The nuclear industry and the Biden administration are pitching coal communities on small, adaptable plants that promoters boast are safer, cheaper and capable of being deployed all over the country in the effort to cut the power sector’s contribution to climate change.

Whether small modular reactors, or SMRs, can realistically be built all over the nation is very much in dispute. The nuclear industry has a record of overpromising and energy scholars warn this new technology is straining to show viability. Two demonstration projects expected to break ground, in Idaho and Wyoming, are behind schedule and struggling with spiraling costs.

But as the United States seeks efficient alternatives to burning fossil fuels for electricity, these proposals for space-age plants that can be small enough to fit in a large backyard feature prominently. They are designed to look more like office parks than nuclear plants, with low rise architecture that replaces concrete with steel, and downsized reactors the administration compares to those the U.S. Navy uses to power ships and submarines.

U.S. climate envoy John F. Kerry said in a recent interview with The Post that the technology’s success is vital for meeting the world’s goal of avoiding the most catastrophic fallout from climate change by limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

“I don’t think we get there without it,” Kerry said.

How Joe Manchin’s change of heart could revive the U.S. solar industry

Coal country is a ripe target for this experiment, with infrastructure that can be repurposed, capable workforces and communities eager to reclaim prominence in the energy economy. More than 300 retired and operating coal plants in the United States are good candidates for a nuclear conversion, according to a recent Department of Energy report that has touched off a frenzy of activity.

Communities that previously rejected nuclear power as unsafe or a threat to the coal industry are now clamoring to be a part of what might be branded nuclear 2.0.

“See that hilltop over there?” said Hatfield, a former coal company engineer who is now the administrator for Wise County. “If you put a nuclear plant someplace like that, it is not going to be near anybody’s backyard. This would keep us in the forefront of the energy business. We see it as our future.”Wise County Administrator Mike Hatfield stands on a former coal property in Big Stone Gap, Va., that was last mined in the late 1980s. It is now the Lonesome Pine Airport. (Mike Belleme for The Washington Post)

In January, billionaire Bill Gates, founder of an advanced nuclear company called TerraPower, toured a mothballed coal power plant near Glasgow, W.Va., with Joe Manchin III, the state’s Democratic senator. Gates was warmly embraced at a town hall following the plant visit. It was a notable turnabout in an area where the style of climate activism personified by Gates has long been met with hostility.

“The way nuclear plants were built, they were just very expensive,” Gates said at the event. “Unless we start from scratch with a new design, we won’t be able to have low-cost electricity.”

It was only a year ago that nuclear power was banned in West Virginia, under a state law intended to protect the coal industry. The state is among several to either lift such a ban or pass a law encouraging development of small nuclear reactors over the last few years. Political leaders see opportunities to boost regional economies and to get a piece of the billions of dollars in subsidies for generating “advanced nuclear” power available through the recently enacted Inflation Reduction Act.

These reactors are still very much a work in progress, with multiple companies pursuing dozens of designs in the hopes of achieving a breakthrough. Some of the designs build on the light-water reactor technology that powers legacy nuclear plants, while others go in entirely different directions. TerraPower would use “fast reactors” cooled with sodium instead of water, potentially enabling them to operate more efficiently and safely than existing plants. Other designs use helium as a coolant.

One glaring challenge with all of the designs: nuclear waste. Designers of the smaller plants vow each facility would produce only a small volume of it, requiring more modest evacuation zones and safety buffers. But scattering hundreds of plants around the country means every community they are in will need to be comfortable with some measure of spent fuel in their backyards, and some prominent researchers are challenging claims that these new reactors create less waste.

The developers are hoping plant designs that keep all the spent fuel contained in the reactor, which stays put for a number of years — even decades — before ultimately getting hauled away could be palatable to communities. But at the moment, there is nowhere to dispose of the used reactors.

“If you are saying, ‘we want to build on this site,’ and the community is asking ‘how long will the waste be here?’ and you have no answer, that is a big problem,” said Jessica Lovering, co-founder of Good Energy Collective, a group that advocates nuclear power as a climate solution.

Political leaders are forging ahead regardless, and officials in coal towns are eagerly pursuing advice from the Department of Energy on how they might draw a small reactor to their locale.

“When you get to a place like this that’s lost all these energy jobs, the talk is not whether it’s coming or not,” said Stephen Lawson, the town manager in Big Stone Gap, Va., a Wise County community where the regal brick building that once housed the Westmoreland Coal Company is now a pottery store. “It is, ‘Who is going to get it? And how do we keep from being left out?’”“When you get to a place like this that’s lost all these energy jobs, the talk is not whether it’s coming or not,” said Stephen Lawson, the town manager in Big Stone Gap, Va. “It is, ‘Who is going to get it? And how do we keep from being left out?’" (Mike Belleme for The Washington Post)

Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s (R) energy plan calls for Southwest Virginia to build the nation’s first commercial small reactor. The governor was in Wise County in October promoting the plan at an abandoned mine site. Virginia is among at least eight states pursuing a small reactor. At least another eight have launched feasibility studies, according to federal energy officials.

That includes Maryland, where a nuclear energy innovation company called X-energy recently partnered with the state and Frostburg State University to show how one of the Maryland’s coal plants could be repurposed for nuclear energy. The final report, published in January, did not identify the specific coal plant studied. X-energy officials said it was because the owner of the plant asked for confidentiality. The omission of a location underscored how carefully proponents of this technology are treading at a time many communities still fear nuclear power is too big a safety and financial risk.

Some places are already reconsidering whether the technology lives up to the talking points. The Pueblo County, Colo., board of commissioners was initially all in, telling state regulators that a modular nuclear plant is the only zero-emissions option for replacing the electricity and economic activity created by the Comanche Generating Station, a hulking coal plant slated for closure in 2030. After a public backlash, the supervisors abandoned the plan.

“A lot of these communities are under pressure because they need to do something now to plan for the closure of coal plants,” said David Schlissel, director of resource planning analysis at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “The marketers of these small modular reactors, who don’t even have products licensed yet, are of course going to tell them the other alternatives are bad. They say you can’t rely on renewables, you can’t rely on battery storage, so they can sell their products. The risk is these places end up with gigantic financial commitments to nuclear projects, some of which are nothing more right now than a Power Point presentation.”

The demonstration modular nuclear project underway at the Idaho National Laboratory has been sobering for nuclear enthusiasts. The developer, NuScale Power, is working on a plant intended to provide electricity to tens of thousands of homes serviced by 27 local power companies across the west. The communities that signed on were expecting to purchase electricity for $58 per megawatt hour, the price stated under the initial agreement.

But by the time the Nuclear Regulatory Commission last month approved the design of the plant — the first such approval in the United States — the expected cost of the energy had gone up more than 50 percent. Some communities pulled out, and others are anxious the costs could rise further by the time the plant goes online, scheduled for December 2029. The cost of the power would be even higher were the plant not so heavily subsidized by the federal government, which has already committed $1.4 billion to develop it and will offset the cost of the electricity it produces by about $30 per megawatt hour, which could cost U.S. taxpayers another $2 billion.

NuScale, which is also angling to build plants in Romania, Poland and Ghana, said in a statement that the cost increases reflect “external factors such as inflationary pressures and increases in the price of steel, electrical equipment and other construction commodities not seen for more than 40 years.”

“Hopefully, the prices won’t get any higher,” said LaVarr Webb, spokesman for the Utah Associated Municipal Power Systems, which represents power companies seeking to buy electricity from the Idaho project. “But that has not yet been proven.”

A project Gates is backing in Kemmerer, Wyo., is having its own challenges. The plant would be fueled by a highly enriched form of uranium that TerraPower planned to initially source from Russia. That plan fell apart with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the sanctions it triggered.

The company announced in December it was pushing back its target date for opening the plant by two years, to 2030. And it is now lobbying Congress to allocate $2.1 billion to subsidize facilities that could produce such uranium in the United States. The request comes after the federal government has already committed $1.6 billion to building the company’s Wyoming plant.

On an industrial plot an hour outside Houston, a much smaller modular nuclear company is trying a completely different approach — one that doesn’t rely on any government subsidies. The company Last Energy plans to use the same technology employed by legacy nuclear plants to create power as cheaply as a natural gas plant. The reactor and much of the core technology fits into a tidy, 30-feet-long-by-30-feet-wide-by-30-feet-high steel box that is mostly assembled off site and can be transported in nine truck trips. Last Energy is only selling its modules to industrial customers in Europe, where the regulatory hurdles are not as cumbersome for new reactor designs.

A sophisticated campaign to find communities that might be amenable to hosting the nuclear plants is underway, coordinated through a University of Michigan-based coalition called Fastest Path to Zero. It has built extensive databases that gauge not just technical suitability for building a plant and transmitting power, but also political suitability. Communities are rated on how amenable they might be to having a nuclear plant in their backyard, based on survey results and other data.

When it comes to finding sites for plants, said Gabrielle Hoelzle, the group‘s lead data scientist, “we are trying to do things in a new way and get it right the first time. We cannot fall into the previous approach of deciding where they will go, announcing it and then trying to defend it.”

Back in Wise County, Mountain Empire Community College, which years ago dropped its underground mining major due to low enrollment, is now mapping out how it can revise course offerings to train a nuclear workforce.

“We’re looking at what are those jobs that are going to be needed if we do get SMRs,” said Kris Westover, president of the college. “We’re trying to make sure that we’re ready.”

By Evan HalperEvan Halper is a business reporter for The Washington Post, covering the energy transition. His work focuses on the tensions between energy demands and decarbonizing the economy. He came to The Post from the Los Angeles Times, where he spent two decades, most recently covering domestic policy and presidential politics from its Washington bureau. Twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment