ICYMI

Markings on the leg and butt bones of early riders indicate people started riding horses 5,000 years ago

Ability to ride horses was likely a big factor in enabling the Yamnayans' continental-scale migration

The bones of horseback riders from thousands of years ago are helping scientists to piece together the story of when and where people first started riding horses.

"Bones are living tissue in your living person and they always react and remodel to handle stress demands, so you can read bones like biographies," said Martin Trautmann, a bioanthropologist from the University of Helsinki.

Trautmann said he wasn't expecting to find evidence of horse riding when he first started studying skeletal remains of Yamnayan people from Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria.

However, while looking at the femur of one particular individual, he saw a sign that he described as "very typical for horse riding." The more he looked, body part by body part, the more signs he saw.

"When I found, later, another skeleton with the same symptoms and then one more and one more and one more, the plausibility that this could just be some random effects became smaller and smaller," Trautmann said.

Early Yamnayans were not mounted warriors, but more like cowboys.- Martin Trautmann, University of Helsinki

Figuring out the skeletons of these people bore marks indicating they were horse riders lends strength to the idea that they were early domesticators of horses.

"This is the first time we've really proven that we had people who were habitual riders in 3,000 BC," said Trautmann's colleague David Anthony, an anthropologist from Harvard University and Hartwick College.

The study describing these findings was published in the journal Science Advances.

Strenuous activity leaves traces on bone

Any time we regularly engage in an activity that requires specific muscles to do — swinging a tennis racquet, throwing a baseball, or riding a horse — the pull from the muscles creates rough patches on the part of the bone where the expanding muscles attach.

"In this case, what you're talking about is an activity in which you're squeezing your thighs and your knees together while you're keeping your legs far apart and bouncing up and down on your tailbone," said Anthony, in an interview with Quirks & Quarks' host, Bob McDonald.

"There are very few activities that require all of that other than horseback riding."

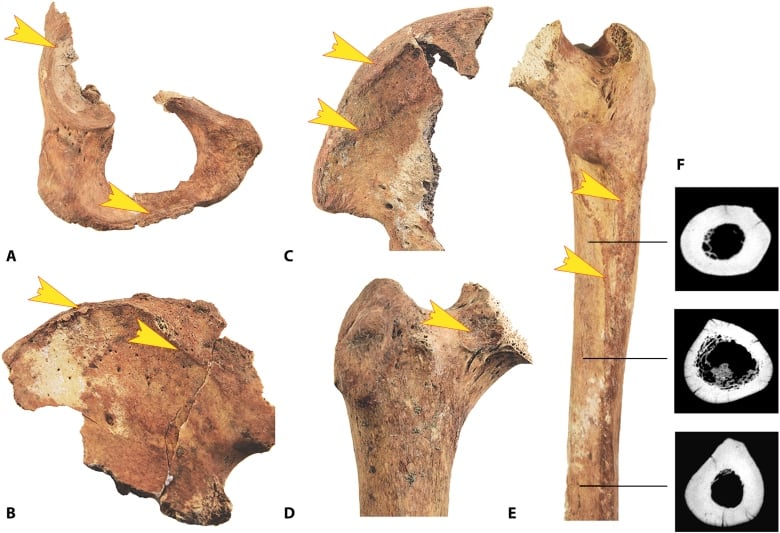

Most of the bone changes in habitual horse riders occur at the muscle, tendon and ligament attachment sites in the thigh bones and pelvis. Other changes can include: deformations in the diameter of the round thigh bones that tend to become oblong-shaped; imprints of thigh bones left behind in the hip sockets; signs of injury in the tailbone and degeneration in the vertebrae.

Detecting many of these characteristic signatures on bone helped the researchers conclude they belonged to horse horse riders.

Putting together the story of horse domestication

Before this new study, everything we knew about the origins of horseback riding came from the horses themselves. The strongest evidence could be found in horse vertebrae, but Anthony said they were rarely well preserved.

So for the past 30 years, Anthony's been working to solve this mystery by studying bit wear left behind on the teeth of ancient horses. The oldest evidence he said he found came from a site in Botai, Kazakhstan, that dated back to sometime between 3,500 and 3,000 B.C. and belonged to the Yamnaya people.

The earliest Yamnayan sites are located in Russia and Ukraine, but they eventually spanned as far as the Mongolian Altai Mountains in the east, and to southeastern Europe in the west, where the human skeletons for this current study originated.

From the human remains Trautmann studied in this work, he estimates that between 20 and 30 per cent of the Yamnayan population at that time were riding horses.

Horse riding was a game-changer

Both Anthony and Trautmann agree that the ability to ride horses, and their eventual domestication, were huge turning points for human civilization.

On horse, the Yamnaya people had the ability to carry more and travel farther than ever before. A 100-kilometre trek that once took 10 days to traverse on foot became a distance a horse rider could complete in a day.

Anthony said the Yamnayans migrated enormous distances east and west, which was partially made possible by horseback riding.

"That's a range of 5,000 kilometers, the equivalent of the Atlantic to the Pacific, the entire width of North America, that's how far these people migrated, and that was unprecedented at the time," explained Anthony.

Riding horses was also revolutionary for herding animals. On horse, it became possible for the Yamnayans to herd three times as many animals, a factor that helped their economy grow.

Using horses for warfare likely came later though because at that time, horses weren't fully domesticated. Anthony said that likely meant they were too skittish to trust in battle.

Trautmann added, "Early Yamnayans were not mounted warriors, but more like cowboys."

Written by Sonya Buyting.

No comments:

Post a Comment