Infrastructure Consulting firm Aecom recently tested the metric on the former location of the Keppel Club golf course.

SINGAPORE – Hoping to see better outcomes for nature before they are affected by building and development projects, a biodiversity specialist had a vision to put a value on all of Singapore’s habitats and land spaces.

Over 1½ years, Mr Ashley Welch and his colleagues from infrastructure consulting firm Aecom, and partners from biodiversity consultancy Camphora, built the Singapore Biodiversity Accounting Metric – a free online calculator that estimates the amount of biodiversity that may be lost from planned building projects.

The tool can be downloaded from this website.

Mr Welch, a biodiversity consultant, is hoping that putting tangible numerical values on habitats and green spaces will spur developers to avoid encroaching on high-value habitats to minimise biodiversity loss.

To calculate the value of a forest or freshwater pond at a development site, the spreadsheet-based tool considers different parameters, including the type and size of the habitat, the condition it is in, its ecological importance and whether it can be replaced. The ecological importance parameter, also known as distinctiveness, is given a score from zero to eight, with eight indicating that the habitat carries very high ecological importance.

For rare habitats or secondary forests dominated by native species, the metric may advise users to avoid touching them at all costs.

A secondary forest will have a higher value than an abandoned carpark with planter boxes, for instance. The value of each land area is represented as numerical biodiversity units. Biodiversity gains and losses in post-development scenarios are shown as percentages.

This tool could spur developers or agencies to build on brownfield sites, or previously developed land, instead of on undeveloped land, said Mr Welch.

But due to limited land space in Singapore, the clearing of more forested land and vegetation is inevitable, he acknowledged. To limit biodiversity loss in these cases, proposed developments should prioritise nature by redesigning the infrastructure to reduce its toll on the environment, enhancing or restoring degraded habitats and introducing urban greenery, he added.

“The metric incentivises you to try and put back as much (nature) as you can to get a better score. There will be projects here that will have a 10 per cent net loss in biodiversity... and it’s better than a 50 per cent net loss,” said Mr Welch.

“Biodiversity accounting assessments encourage us to break down the complexity of nature and allow us to make better decisions that the average person would have otherwise been unaware of.”

The tool is designed to be used at a project’s master planning stage or alongside environmental impact assessments and field surveys. The metric can currently calculate the values of terrestrial, freshwater and intertidal habitats.

Environment consultancy DHI Group, for instance, has a biodiversity metric for the marine environment called EBM BioQ.

SINGAPORE – Hoping to see better outcomes for nature before they are affected by building and development projects, a biodiversity specialist had a vision to put a value on all of Singapore’s habitats and land spaces.

Over 1½ years, Mr Ashley Welch and his colleagues from infrastructure consulting firm Aecom, and partners from biodiversity consultancy Camphora, built the Singapore Biodiversity Accounting Metric – a free online calculator that estimates the amount of biodiversity that may be lost from planned building projects.

The tool can be downloaded from this website.

Mr Welch, a biodiversity consultant, is hoping that putting tangible numerical values on habitats and green spaces will spur developers to avoid encroaching on high-value habitats to minimise biodiversity loss.

To calculate the value of a forest or freshwater pond at a development site, the spreadsheet-based tool considers different parameters, including the type and size of the habitat, the condition it is in, its ecological importance and whether it can be replaced. The ecological importance parameter, also known as distinctiveness, is given a score from zero to eight, with eight indicating that the habitat carries very high ecological importance.

For rare habitats or secondary forests dominated by native species, the metric may advise users to avoid touching them at all costs.

A secondary forest will have a higher value than an abandoned carpark with planter boxes, for instance. The value of each land area is represented as numerical biodiversity units. Biodiversity gains and losses in post-development scenarios are shown as percentages.

This tool could spur developers or agencies to build on brownfield sites, or previously developed land, instead of on undeveloped land, said Mr Welch.

But due to limited land space in Singapore, the clearing of more forested land and vegetation is inevitable, he acknowledged. To limit biodiversity loss in these cases, proposed developments should prioritise nature by redesigning the infrastructure to reduce its toll on the environment, enhancing or restoring degraded habitats and introducing urban greenery, he added.

“The metric incentivises you to try and put back as much (nature) as you can to get a better score. There will be projects here that will have a 10 per cent net loss in biodiversity... and it’s better than a 50 per cent net loss,” said Mr Welch.

“Biodiversity accounting assessments encourage us to break down the complexity of nature and allow us to make better decisions that the average person would have otherwise been unaware of.”

The tool is designed to be used at a project’s master planning stage or alongside environmental impact assessments and field surveys. The metric can currently calculate the values of terrestrial, freshwater and intertidal habitats.

Environment consultancy DHI Group, for instance, has a biodiversity metric for the marine environment called EBM BioQ.

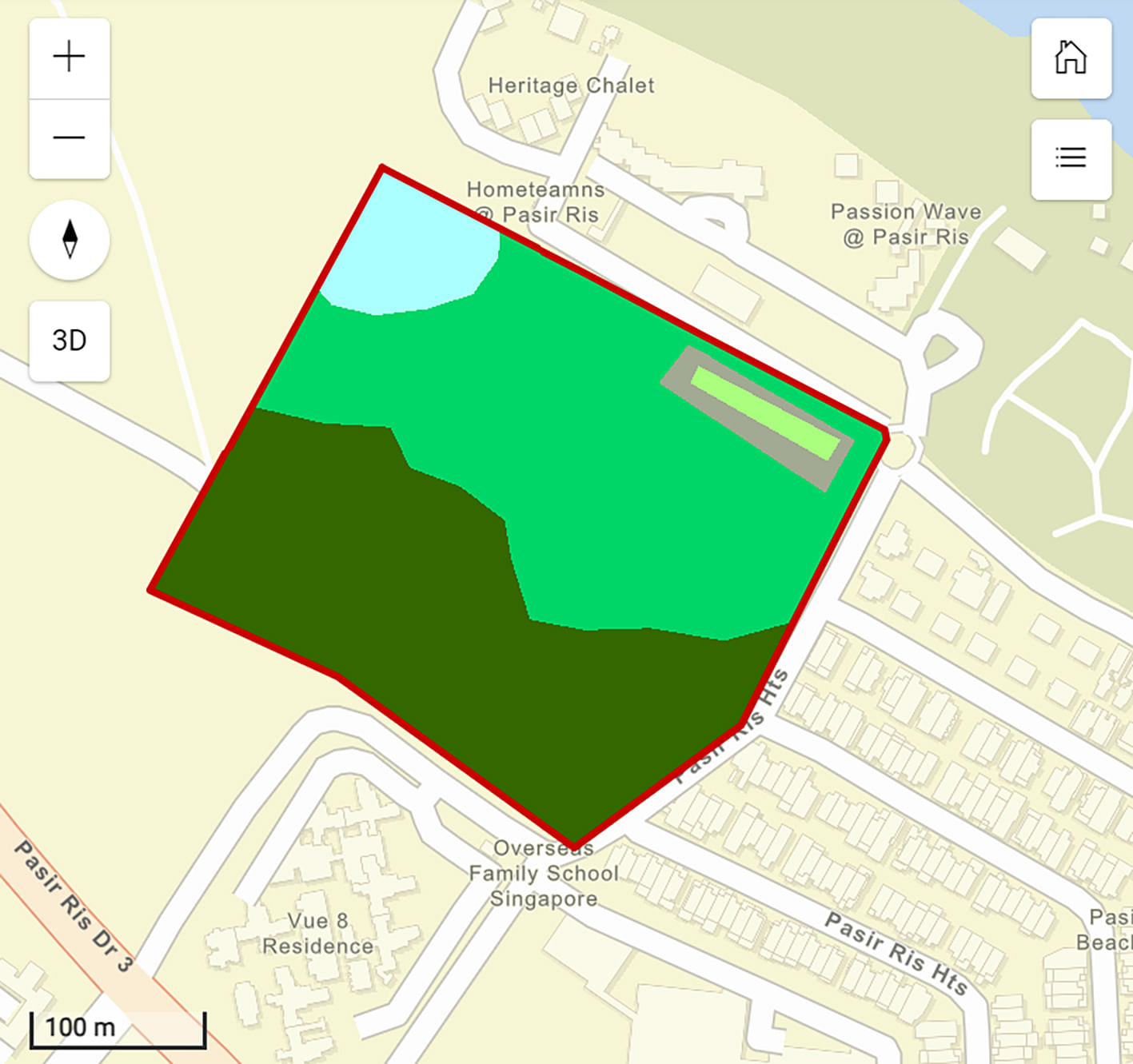

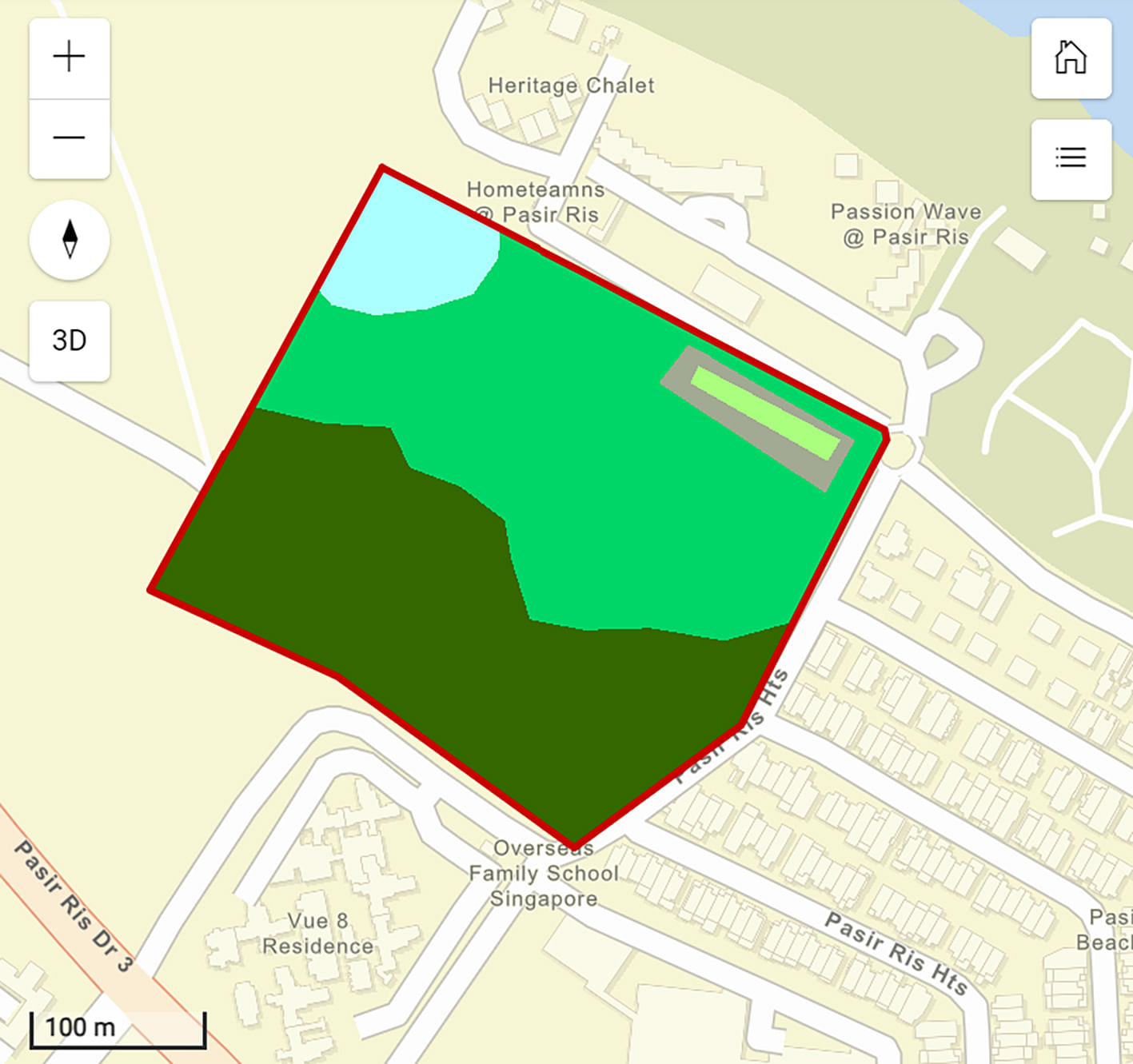

The metric can currently calculate the values of terrestrial, freshwater and intertidal habitats. PHOTO: SINGAPORE BIODIVERSITY ACCOUNTING METRIC

A key reason that drove Mr Welch to build the metric was to reduce the subjectivity with environmental impact assessments and their following mitigation measures.

Dr Anuj Jain, founding director of bioSEA, a company that specialises in ecological design, agreed that a site’s value can be interpreted differently by consultants.

“The tool presents a standard set of values that can be collectively debated and agreed upon by the conservation and ecology community,” he said.

“In the past, projects have also got around to clearing ecologically valuable forested areas and replacing them with streetscapes and park connectors. In cases where the impact of development is huge, the tool may be able to help save valuable ecological habitats from being developed.”

Aecom and Camphora have been using the tool on some master planning work and environmental impact assessments, but they are unable to disclose the ongoing projects.

Aecom recently tested the metric on a 48ha site in the Greater Southern Waterfront, which will be redeveloped to house around 9,000 public and private housing units. In 2022, the authorities said the first Build-To-Order project would be launched for sale within three years.

The company previously conducted an environmental impact study on the site and its connecting green spaces, and later used the tool to check if its proposed mitigation measures were optimal.

The site, which is the former location of the Keppel Club golf course, has three high-value habitats bordering it, said Mr Welch. They are Berlayer Creek, which is one of two remaining mangrove patches in southern Singapore, the Bukit Chermin secondary forest dominated by native trees, and a marine area with seagrass meadows and rocky shores.

The first decision made was to leave those high-value habitats untouched.

As for the 48ha golf course, it was a nesting and foraging ground for birds and acted as an ecological bridge between the Southern Ridges and Labrador Nature Reserve.

To help preserve the site’s connectivity for wildlife, the authorities have announced that green corridors will be formed alongside the housing blocks, with one running through the future estate, and another next to Berlayer Creek to buffer the vulnerable habitat from urban light and noise.

A key reason that drove Mr Welch to build the metric was to reduce the subjectivity with environmental impact assessments and their following mitigation measures.

Dr Anuj Jain, founding director of bioSEA, a company that specialises in ecological design, agreed that a site’s value can be interpreted differently by consultants.

“The tool presents a standard set of values that can be collectively debated and agreed upon by the conservation and ecology community,” he said.

“In the past, projects have also got around to clearing ecologically valuable forested areas and replacing them with streetscapes and park connectors. In cases where the impact of development is huge, the tool may be able to help save valuable ecological habitats from being developed.”

Aecom and Camphora have been using the tool on some master planning work and environmental impact assessments, but they are unable to disclose the ongoing projects.

Aecom recently tested the metric on a 48ha site in the Greater Southern Waterfront, which will be redeveloped to house around 9,000 public and private housing units. In 2022, the authorities said the first Build-To-Order project would be launched for sale within three years.

The company previously conducted an environmental impact study on the site and its connecting green spaces, and later used the tool to check if its proposed mitigation measures were optimal.

The site, which is the former location of the Keppel Club golf course, has three high-value habitats bordering it, said Mr Welch. They are Berlayer Creek, which is one of two remaining mangrove patches in southern Singapore, the Bukit Chermin secondary forest dominated by native trees, and a marine area with seagrass meadows and rocky shores.

The first decision made was to leave those high-value habitats untouched.

As for the 48ha golf course, it was a nesting and foraging ground for birds and acted as an ecological bridge between the Southern Ridges and Labrador Nature Reserve.

To help preserve the site’s connectivity for wildlife, the authorities have announced that green corridors will be formed alongside the housing blocks, with one running through the future estate, and another next to Berlayer Creek to buffer the vulnerable habitat from urban light and noise.

A page in the Singapore Biodiversity Accounting Metric which shows users how to use the tool. PHOTO: SINGAPORE BIODIVERSITY ACCOUNTING METRIC

The tool calculated a 10 per cent net gain in biodiversity with those proposed changes – a rare instance where development seems to give nature a boost.

“The project prioritised development on a habitat suboptimal for biodiversity, a golf course. The green corridors – comprising a secondary forest and some urban streetscapes – will connect with the existing forest and mangroves,” said Mr Welch.

The tool is loosely based on a British biodiversity metric created by conservation agency Natural England.

In Britain, such metrics are part of policy. From November, new housing and commercial projects there must ensure that their developments leave habitats in a better state than before, with at least a 10 per cent gain in biodiversity. This can be done by restoring a habitat off-site, but as a last resort.

Mr Welch and his team are looking to improve the metric – which was built with the help of a grant from the Economic Development Board – with feedback from other consultants and the nature community. They aim to eventually create a similar tool for the whole of South-east Asia.

Assistant Professor Lim Jun Ying from the National University of Singapore’s Department of Biological Sciences noted that any methods or metrics relying on biodiversity values should be regarded as a convenient “shorthand” based on available data.

“In reality, species with different attributes will respond to land-use changes in different ways, and over different timeframes... It is important to remember that there are many aspects of biodiversity and ecosystems that are hard to capture quantitatively,” he said.

The tool calculated a 10 per cent net gain in biodiversity with those proposed changes – a rare instance where development seems to give nature a boost.

“The project prioritised development on a habitat suboptimal for biodiversity, a golf course. The green corridors – comprising a secondary forest and some urban streetscapes – will connect with the existing forest and mangroves,” said Mr Welch.

The tool is loosely based on a British biodiversity metric created by conservation agency Natural England.

In Britain, such metrics are part of policy. From November, new housing and commercial projects there must ensure that their developments leave habitats in a better state than before, with at least a 10 per cent gain in biodiversity. This can be done by restoring a habitat off-site, but as a last resort.

Mr Welch and his team are looking to improve the metric – which was built with the help of a grant from the Economic Development Board – with feedback from other consultants and the nature community. They aim to eventually create a similar tool for the whole of South-east Asia.

Assistant Professor Lim Jun Ying from the National University of Singapore’s Department of Biological Sciences noted that any methods or metrics relying on biodiversity values should be regarded as a convenient “shorthand” based on available data.

“In reality, species with different attributes will respond to land-use changes in different ways, and over different timeframes... It is important to remember that there are many aspects of biodiversity and ecosystems that are hard to capture quantitatively,” he said.

No comments:

Post a Comment