Hammer & Hope co-founder Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor has written a new introduction for an expanded second edition of How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective, which includes the groundbreaking statement, along with interviews and essays reflecting on its impact, among them a new interview with Angela Y. Davis. In this excerpt from the introduction, Taylor describes the emergence in the early 1970s of a distinct current of Black feminism, contending with multiple concerns, that would give rise to the Combahee collective.

Black feminism never developed into a mass movement in the way that the mostly white women’s liberation movement of the 1960s and ’70s did. Most Black women remained in the Black liberation movement, even as they tried to make the movement address their concerns about women’s oppression. By the early 1970s, for example, it’s likely that a majority of members of the Black Panther Party were women, as the organization began to focus less on armed confrontation with police and more on mutual aid organizing and community-based activism, like the free breakfast program, which reflected the kinds of concerns that animated Black feminist consciousness and politics. Black women already had prominent roles in community organizing without forming new organizations, which would have been regarded with the hostility typical among men in the Black liberation movement at that time. Historian Premilla Nadasen has argued that Black women’s struggles for greater access to welfare rights should be understood as a critical part of Black feminist organizing, which would deepen our understanding of Black feminism as an organizing project. She argues that “the welfare rights movement was one of the most important organizational expressions of the needs and demands of poor Black women. Predating the outpouring of Black feminist literature in the 1970s, women in the welfare rights movement challenged some of the basic assumptions offered by other feminists — white and Black — and articulated their own version of Black feminism.”

But outside of the structures of a social movement or organization, the changing political economy of the 1960s meant that millions of ordinary Black women were radicalized by their economic marginalization and poverty amid American affluence. Meanwhile another cohort of Black women was rising into the middle class through the emergence of better jobs in government and the public sector, along with greater access to colleges and universities. In a note for a 1966 special issue on “The Negro Woman,” Ebony publisher John H. Johnson described the dual fortunes of Black women: “She still cleans the houses and cooks the food of Miss Anne but she also computes the figures for planned space shots and does cancer research in hospital laboratories. She is still the ‘mammy’ to many a wealthy white woman’s child but she has also seen her own son graduated magna cum laude from Ivy League colleges. While she is still arrested for prostitution on Chicago’s North Clark Street, she also sits as ambassador representing her country abroad.”

Thus, a “golden cohort” of Black women writers and artists — daughters of the Black poor and working class — helped to define the terms of Black women’s radicalization in broader terms, even as it was overlooked in the white feminist movement. The legal scholar, civil rights activist, and NOW co-founder Pauli Murray argued, “In the face of their multiple disadvantages, it seems clear that black women can neither postpone nor subordinate the fight against sex discrimination to the black evolution.” When the writer and educator Toni Cade Bambara edited a collection of Black women’s writing, The Black Woman: An Anthology, in 1970, she began the volume by declaring, “We are involved in a struggle for liberation: liberation from the exploitive and dehumanizing system of racism, from the manipulative control of a corporate society. … If we women are to get basic, then surely the first job is to find out what liberation for ourselves means, what work it entails, what benefits it will yield.” She asked what the “feminist literature,” including The Feminine Mystique, had to do with Black women: “How relevant are the truths, the experiences, the findings of white women to Black women? Are women after all simply women? I don’t know that our priorities are the same, that our concerns and methods are the same, or even similar enough so that we can afford to depend on this new field of experts (white, female).”

For other women, such as the rising political figures Shirley Chisholm of New York and Barbara Jordan of Texas, the world of Democratic Party politics opened new opportunities for political change. But the entry into mainstream politics further revealed the hostility experienced by Black women, especially from Black men. One Black man opposing Chisholm’s feminist agenda commented, “You can’t equate the problems of women and the problems of blacks, whatever Shirley says,” adding, “Women simply aren’t exploited or denied opportunity on the same basis.” Even though Chisholm was running a left-wing, antiwar campaign for the Democratic Party presidential nomination, the National Black Political Convention in Gary, Ind., in March 1972 did not endorse her candidacy.

In 1974, the Combahee River Collective, a group of Black lesbians based in Boston, organized themselves as a break to the left from a more conventional national organization called the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO), which itself had been formed as a Black-oriented version of the National Organization for Women. Murray, a co-founder of NOW, had left the group, feeling that it was overly focused on middle-class white women. The NBFO’s founding statement in 1973 explained that the group’s emergence was necessary to “strengthen the current efforts of the Black Liberation struggle in this country by encouraging all of the talents and creativities of black women to emerge, strong and beautiful, not to feel guilty or divisive, and assume positions of leadership and honor in the black community. … We will continue to remind the Black Liberation Movement that there can’t be liberation for half the race.”

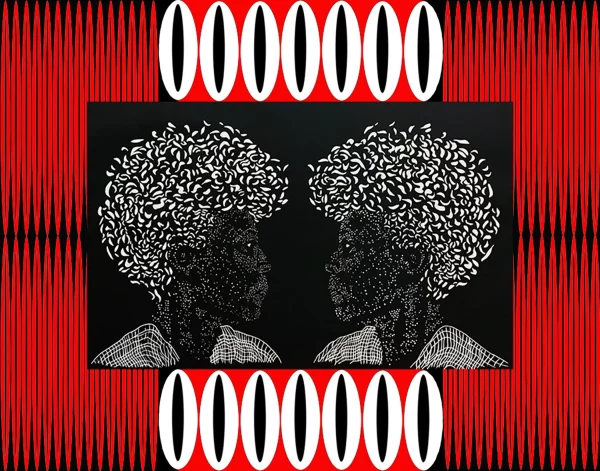

Barbara Smith and her twin sister, Beverly, who helped to found the Combahee River Collective, were initially active in the NBFO chapter in Boston. But they broke away to form a new group “since we had serious disagreements with NBFO’s bourgeois-feminist stance and their lack of a clear political focus,” as the Combahee statement later explained.

The Combahee River Collective engaged in local campaigns across Boston, but it was never very large and mostly focused on internal consciousness-raising and political education. The collective is best known for its powerful statement, drafted in 1977 at the request of Zillah R. Eisenstein, who wanted to include it in her anthology Capitalist Patriarchy and the Case for Socialist Feminism.

As Barbara Smith, a co-author of the statement, said of its significance: “The concept of the simultaneity of oppression is still the crux of a Black feminist understanding of political reality and, I believe, one of the most significant ideological contributions of Black feminist thought. We examined our own lives and found that everything out there was kicking our behinds — race, class, sex, and homophobia. We saw no reason to rank oppressions or, as many forces in the Black community would have us do, to pretend that sexism, among all ‘isms,’ was not happening to us.”

The Combahee River Collective is also widely recognized for introducing the phrase identity politics to explain its orientation toward politics in the 1970s. Smith identified three main reasons why Black women began to organize separately and with their own agenda:

1. “The racism of white women in the women’s movement”;

2. Third world men who sought “to maintain power over ‘their women’ at all costs”; and

3. “White men and Third World men, ranging from conservatives to radicals,” who “pointed to the seeming lack of participation of women of color in the movement in order to discredit” feminism “and to undermine the efforts of the movement as a whole.”

For Smith and her contemporaries, these obstacles to the inclusion of Black women within movement spaces inevitably meant that Black women’s issues were not taken seriously and would be addressed only through their own organizing efforts — thus the centrality of identity. Yet Smith has repeatedly emphasized that the collective did not see this as necessarily hostile to coalition politics, something they, in fact, routinely practiced. While the historical context necessitated Combahee’s theorization of “identity politics,” the material pressures bearing down on Black women made alliances with others indispensable to their survival.

Pauli Murray recognized this need for coalition when she argued, “By asserting a leadership role in the growing feminist movement, the black woman can help to keep it allied to the objectives of black liberation while simultaneously advancing the interests of all women.” One year earlier, the Black feminist Mary Ann Weathers had described how to develop unity based on the mutual interests of women: “All women suffer oppression, even white women, particularly poor white women, and especially Indian, Mexican, Puerto Rican, [Asian], and black American women whose oppression is tripled by any of the above mentioned. But we do have female’s [sic] oppression in common. This means that we can begin to talk to other women with this common factor and start building links with them and thereby build and transform the revolutionary force we are now beginning to amass.”

But Fran Beal mapped out the obstacles to this kind of coalition: “If the white groups do not realize that they are in fact fighting capitalism and racism, we do not have common bonds. If they do not realize that the reasons for their condition lie in the system and not simply that men get a vicarious pleasure out of ‘consuming their bodies for exploitative reasons’ … then we cannot unite with them around common grievances or even discuss these groups in a serious manner because they’re completely irrelevant to the black struggle.” However, Beal did not spell out the means by which Black women could overcome their oppression — if a mass movement that included groups beyond Black or other third world women was necessary.

Years after the publication of the Combahee statement and greatly influenced by the observations of the writer Audre Lorde (who took part in Combahee Collective retreats), Barbara Smith noted the importance of respecting “difference” in politics: “I will never forget the period of Black nationalism, power, and pride that, despite its benefits, had a stranglehold on our identities. A blueprint was made for being Black and Lord help you if you deviated in the slightest way. … How relieved we were to find, as our awareness increased and our own Black women’s movement grew, that we were not crazy, that the brothers had in fact created a sex-biased definition of ‘Blackness’ that served only them.”

She went on to caution against a strain of thought then seeping into the Black women’s movement: “In finding each other, some of us have fallen into the same pattern. … I am not saying that any particular group of Black women does this more than others, because at times we can all fall prey to the ‘jugular vein’ mentality, as [Audre] Lorde terms it, and want to kill or erase from our universe anyone unlike us.” The movement would need to overcome differences, because our liberation “will not come about, as Bernice Johnson Reagon puts it, inside our ‘little barred rooms.’”

Smith emphasized the distinction between organizing autonomously to ensure that a political agenda is developed around a particular set of issues and making separatism a matter of principle. She quoted Cheryl Clarke’s observation that we “have to accept or reject allies on the basis of politics not on the specious basis of skin color. Have not black people suffered betrayal from our own people?” Even more consequently, Smith noted, “The worst effect of separatism is not upon whomever we define as ‘enemy,’ but upon ourselves as it isolates us from each other.”

Beyond recognizing that the differences existed, neither Lorde nor Smith clarified how to overcome these differences in political terms. The notion of identity politics and even coalition politics as a response are simply ways of negotiating and coexisting with those differences. Overcoming difference is not the same as washing it away. Instead, political solidarity is a recognition that we have a mutual interest in organizing together to create a political force that can change the conditions that we all suffer from, even if that suffering looks different based on social position.

Excerpted from the introduction to the second edition of How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective, edited by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor and published by Haymarket Books. Reprinted with permission.

No comments:

Post a Comment