Ernie LaPointe petitioned US gov't for permission to relocate his ancestor's remains.

JENNIFER OUELLETTE - 10/27/2021

Enlarge / Hair from Lakota Sioux leader Sitting Bull’s scalp lock, from which DNA was extracted for analysis.

Eske Willerslev

An international team of scientists has confirmed the lineage of a living descendent of the famous Lakota Chief Sitting Bull via a new method of DNA analysis designed to track familial lineage using ancient DNA fragments. According to the authors of a new paper published in the journal Science Advances, this is the first time that such an analysis has been used to confirm a link between deceased and living people—in this case, Sitting Bull and his great-grandson, Ernie LaPointe.

The team's method should be broadly applicable to any historical question involving even the limited genetic data gleaned from ancient DNA. “In principle, you could investigate whoever you want—from outlaws like Jesse James to the Russian tsar’s family, the Romanovs," said co-author Eske Willerslev of the University of Cambridge. "If there is access to old DNA, typically extracted from bones, hair or teeth, they can be examined in the same way."

Sitting Bull (Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake) was a Lakota leader who is best known for his defeat of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer's 7th Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Big Horn (aka, the Battle of the Greasy Grass) on June 25-26, 1876. Various tribes had been joining Sitting Bull's camp over the preceding months, drawn by his spiritual leadership and seeking safety in numbers against US troops. Their number soon grew to more than 10,000. Custer's men were badly outnumbered when they attacked the camp and were forced to retreat. The Sioux warriors ultimately killed Custer and most of his men in what was later dubbed Custer's Last Stand.

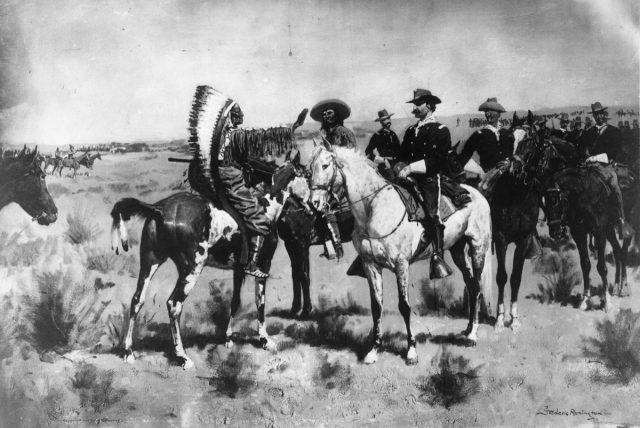

Enlarge / October 1876: General Nelson Miles talking with Chief Sitting Bull after the army's defeat at Little Big Horn. Original Artist: Frederic Remington (1861-1909).

MPI/Getty Images

That victory proved to be short-lived. The US dispatched thousands more soldiers to the region, and over the next year, many tribes chose to surrender. Sitting Bull was not among them, preferring to lead his tribe to Canada's Northwest Territories instead (what is now Saskatchewan AND ALBERTA)

He stayed there for four years, despite offers of a pardon, until it became clear that his people couldn't survive, because the buffalo herds were too small to support their food needs. Sitting Bull and his people returned to the US and surrendered on July 19, 1881, to Major David H. Brotherton at Fort Buford. (The chief purportedly told Brotherton, "I wish it to be remembered that I was the last man of my tribe to surrender my rifle.")

The group (some 186 people in all) was kept at Fort Yates, adjacent to the Standing Rock Agency, apart from a 20-month stint at Fort Randall. Sitting Bull gained a certain amount of celebrity in 1884 when he was allowed to tour the US and Canada with a show called the Sitting Bull Connection. He met Annie Oakley on that tour, in Minnesota, and was so impressed with her firearms skills that he symbolically "adopted" her as his daughter and dubbed her "Little Sure Shot." Oakley used the moniker for most of her career. In 1885, Sitting Bull toured with Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West show for four months, where his "performance" consisted of riding once around the arena each night as the audience gawked.

Meanwhile, tensions continued to increase between Sitting Bull and US Indian Agent James McLaughlin as the US government divided up and sold parts of the Great Sioux Reservation. By 1889, a religious "Ghost Dance" movement—which involved dancing and chanting for the resurrection of deceased relatives and the return of the buffalo herds—was gaining strength, alarming nearby white settlers. Sitting Bull wasn't a participant, but he did allow the dancers on his camping grounds, so McLaughlin ordered the chief's arrest.

Enlarge / Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill Cody, photographed ca. 1880 in Montreal, Canada.

Bettmann/Getty Images

Sitting Bull did not go quietly when 39 police officers knocked on his door at 5:30 in the morning on December 15, 1890. The noise awakened his supporters, who were enraged at this treatment. One Lakota, Catch-a-Bear, shot an officer, who responded by shooting Sitting Bull in the chest. Another officer shot the chief in the head. All told, six officers, Sitting Bull, and seven of his supporters were killed in the skirmish. Sitting Bull was buried at Fort Yates for several decades, until Lakota family members exhumed his body and relocated the remains near his birthplace in Mobridge, South Dakota.

Enter Ernie LaPointe, president and founder of the Sitting Bull Family Foundation and great-grandson of the Lakota Sioux chief. LaPointe and his sisters—Marlene Little Spotted Horse Andersen, Ethel Little Spotted Horse Bates, and Lydia Little Spotted Horse Red Paint—have petitioned the US government for permission to relocate the remains yet again, this time to the Battle of Little Big Horn site, which they believe held more personal meaning for Sitting Bull.

Having DNA analysis to reinforce their familial claims would be enormously helpful in achieving that goal. "Over the years, may people have tried to question the relationship that I and my sisters have to Sitting Bull," said LaPointe. His claim until now had been based upon written historical records, birth and death certificates, and a family tree.

And a DNA source was readily available, with no need to exhume the body yet again. Before Sitting Bull was buried, the post surgeon at Fort Yates, H. Deeble, took a couple of souvenirs—without anyone's permission or authority, the authors note. Deeble kept the Lakota Sioux leader's cloth leggings and the hair lock at the crown of his head (known as a scalp lock) and subsequently loaned them to the Smithsonian Institution in 1896. They remained at the museum until 2007, when LaPointe requested that the items be repatriated. His request was granted, and news of the repatriation soon reached Willerslev.

Enlarge / Ernie LaPointe, now confirmed by DNA analysis to be the great-grandson of Sitting Bull, in November 2016.

Ingo Wagner/Getty Images

“Sitting Bull has always been my hero, ever since I was a boy," said Willerslev. "I admire his courage and his drive. That’s why I almost choked on my coffee when I read in a magazine in 2007 that the Smithsonian Museum had decided to return Sitting Bull’s hair to Ernie LaPointe and his three sisters, in accordance with new US legislation on the repatriation of museum objects."

Willerslev wrote to LaPointe explaining his admiration and his scientific expertise in analyzing ancient DNA. He requested permission to compare the DNA of LaPointe and his sisters with any DNA he was able to extract from the scalp lock, thereby providing strong evidence of their ancestry. LaPointe agreed and provided a small portion of the scalp lock for analysis.

Unfortunately, the task proved to be far more challenging than Willerslev had expected, because the DNA in the sample was so badly degraded. It took 14 years, in fact, for his team to figure out the best method for extracting the DNA and analyzing it. Most approaches to DNA analysis involve hunting for a genetic match between specific DNA passed down through either the paternal or maternal line. But these methods aren't always reliable.

"Since many human mitochondrial and Y-chromosome haplogroups are common, even unrelated individuals can have the same haplogroup just by chance," the authors wrote. "Therefore, these markers can be primarily used to rule out familial relationships. They rarely provide strong evidence supporting that two individuals are related or the determination of a specific familial relationship."

Enlarge / The grave of Sioux Chief Sitting Bull in South Dakota, where his remains were transferred after several decades from the original burial site in North Dakota.

Chris Melzer/picture alliance/Getty Images

Instead, Willerslev et al. employed a technique that searches for so-called "autosomal DNA" in the genetic fragments they were able to extract and sequence from Sitting Bull's hair sample. We inherit half such DNA from our fathers and half from our mothers, so one can check for genetic matches regardless of whether one is descended from the paternal or maternal line.

“Autosomal DNA is our non-gender-specific DNA," said Willerslev. "We managed to locate sufficient amounts of autosomal DNA in Sitting Bull’s hair sample, and compare it to the DNA sample from Ernie LaPointe and other Lakota Sioux—and were delighted to find that it matched."

There were some complications along the way. Since it's not possible to get sufficiently clear data just by looking at the DNA, Willerslev et al.'s argument is essentially based on statistics. "The new approach requires data from at least a few individuals from the same population as the individuals of interest," the authors wrote. "It also requires that none of the individuals included in the analysis are admixed or inbred, since it relies on having representative allele frequencies."Advertisement

Willerslev's team collected spit samples from LaPointe and 13 unrelated Lakota Sioux individuals and sequenced that genetic data for comparison to the Sitting Bull sample. But data from the latter was too limited to make a definitive call on LaPointe's lineage, and only five of the individuals (including LaPointe) met the requirement of no admixing; the others showed evidence of some European ancestry. So the team developed its own probabilistic method that could process both limited sequencing data from a historical figure and SNP chip data—DNA microarrays that test genetic variation at many hundreds of thousands of specific locations across the genome—from a living individual. They also conducted several simulations to verify the certainty of the results.

In the end, the team was able to determine that LaPointe is, indeed, Sitting Bull's great-grandson, thereby providing genetic evidence that "he and his sisters are the rightful recipients of the repatriated items from the Smithsonian Institution," the authors concluded. The next step is to analyze the remains buried at the Mobridge site to confirm that they are a genetic match to Sitting Bull.

DOI: Science Advances, 2021. 10.1126/sciadv.abh2013 (About DOIs).

No comments:

Post a Comment