Tuesday, November 23rd 2021

Full article0 comments

‘Cetacean Strandings from Space’ infographic created by Lead Author Penny Clarke.

An international team of scientists led by the British Antarctic Survey have published research on using new technology to study mass stranding of whales from space and how the technology could be used to help protect populations.

The study published in Frontiers in Marine Science found that studying high–resolution satellite imagery could help build long–term cetacean (i.e. whales, dolphins and porpoises) stranding monitoring programs in remote regions and stranding networks globally. The team behind the study includes scientists from British Antarctic Survey, CEAZA (Center for Advanced Research in Arid Zones), Oceanswell and the University of Massey.

Whale strandings are becoming a critical ocean health issue and an increase in capacity to monitor and understand strandings is urgently required. The World Health Organization recently announced their ‘One Health’ approach, which recognizes oceanic conditions that impact whales often affect the marine ecosystem, with potential ramifications for human health too. Leading marine mammal experts made whale stranding response one of three core goals of the World Marine Mammal Conference in 2019.

The researches discuss making satellites a viable long-term monitoring tool, particularly for places where stranding response capacity is very limited and where surveys are infrequent. For remote regions, satellites could form an ‘early response’ tool, alerting managers to a problem and allowing for appropriate response, which could increase the likelihood of attaining useful diagnostic samples to understand exactly what is causing these events.

Penny Clarke, Lead Author of the study and PhD Researcher at British Antarctic Survey, said: “This study reveals that we need to increase the monitoring of mass strandings across the globe to greater understand cetacean populations, the threats they face and to evaluate the impact of future change. This is particularly important in remote regions, absent of stranding monitoring networks, where satellites offer an opportunity to gather baseline data in these regions.”

Dr Jennifer Jackson, Whale Biologist at British Antarctic Survey said: “As whale populations recover from whaling and suffer growing impacts from humans and from climate change, we need new tools to monitor these impacts, particularly in remote areas. Satellites hold a lot of promise for helping monitor those strandings over huge areas, as well as to look at local sea conditions, to help identify the causes faster, and make the right recommendations for ocean protection and management.”

Dr Asha de Vos, Founder and Executive Director of Oceanswell in Sri Lanka said: “Strandings happen across all our coastlines, but not all of us are equipped to monitor or document these events. Satellites provide us with a unique opportunity to monitor even the most far flung places but the key thing is increasing access. If we want to truly understand and protect our planet, we need to ensure equitable access to tools that can help us solve our greatest challenges together.”

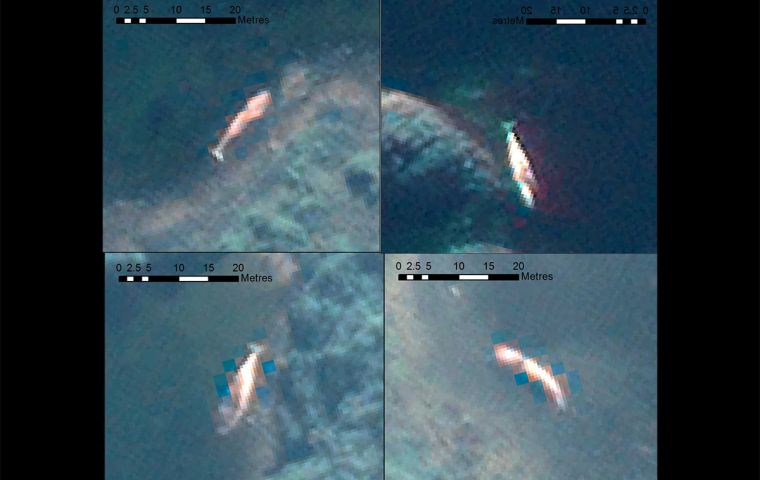

The team analyzed satellite imagery collected from the Golfo de Penas, Chile in 2019, an area of annually recurring mass stranding events and the location of the original largest known mass stranding of baleen whales in 2015. The results show the power of satellites to deduce the timings of events, which could be vital for long-term monitoring programs.

The international team hope to challenge the current disparity in stranding monitoring efforts through use of satellites. They also call for collaborative partnerships between satellite providers and stranding networks governments and NGOs, for equal access to satellite imagery, a recommendation endorsed by the International Whaling Commission Scientific Committee.

The research highlights the importance of collaborating across remote sensing specialisms to determine if satellites may help understand the environmental and human induced conditions before, during and after a mass stranding event. Other remotely sensed data could help to highlight changes in the ocean environment and to provide an early warning system to mitigate mass stranding events and develop more informed, knowledgeable and rapid response stranding networks.

Moving forward, the team plan to test the robustness of this technology by partnering with existing and efficient stranding networks in hotspot areas, such as New Zealand, to develop working protocols and automated detection procedures. Following this they will concentrate on remote priority locations such as: the Chilean Patagonia region; much of the West and Eastern coastlines of Africa; the Polar Regions; and coasts in politically turbulent regions such as the North West Indian Ocean.

Cetacean strandings from space: Challenges and opportunities of very high resolution satellites for the remote monitoring of cetacean mass strandings by Penny J. Clarke, Hannah C. Cubaynes, Karen A. Stockin, Carlos Olavarria, Asha de Vos, Peter T. Fretwell and Jennifer A. Jackson is published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science. Read the paper on their website

An international team of scientists led by the British Antarctic Survey have published research on using new technology to study mass stranding of whales from space and how the technology could be used to help protect populations.

The study published in Frontiers in Marine Science found that studying high–resolution satellite imagery could help build long–term cetacean (i.e. whales, dolphins and porpoises) stranding monitoring programs in remote regions and stranding networks globally. The team behind the study includes scientists from British Antarctic Survey, CEAZA (Center for Advanced Research in Arid Zones), Oceanswell and the University of Massey.

Whale strandings are becoming a critical ocean health issue and an increase in capacity to monitor and understand strandings is urgently required. The World Health Organization recently announced their ‘One Health’ approach, which recognizes oceanic conditions that impact whales often affect the marine ecosystem, with potential ramifications for human health too. Leading marine mammal experts made whale stranding response one of three core goals of the World Marine Mammal Conference in 2019.

The researches discuss making satellites a viable long-term monitoring tool, particularly for places where stranding response capacity is very limited and where surveys are infrequent. For remote regions, satellites could form an ‘early response’ tool, alerting managers to a problem and allowing for appropriate response, which could increase the likelihood of attaining useful diagnostic samples to understand exactly what is causing these events.

Penny Clarke, Lead Author of the study and PhD Researcher at British Antarctic Survey, said: “This study reveals that we need to increase the monitoring of mass strandings across the globe to greater understand cetacean populations, the threats they face and to evaluate the impact of future change. This is particularly important in remote regions, absent of stranding monitoring networks, where satellites offer an opportunity to gather baseline data in these regions.”

Dr Jennifer Jackson, Whale Biologist at British Antarctic Survey said: “As whale populations recover from whaling and suffer growing impacts from humans and from climate change, we need new tools to monitor these impacts, particularly in remote areas. Satellites hold a lot of promise for helping monitor those strandings over huge areas, as well as to look at local sea conditions, to help identify the causes faster, and make the right recommendations for ocean protection and management.”

Dr Asha de Vos, Founder and Executive Director of Oceanswell in Sri Lanka said: “Strandings happen across all our coastlines, but not all of us are equipped to monitor or document these events. Satellites provide us with a unique opportunity to monitor even the most far flung places but the key thing is increasing access. If we want to truly understand and protect our planet, we need to ensure equitable access to tools that can help us solve our greatest challenges together.”

The team analyzed satellite imagery collected from the Golfo de Penas, Chile in 2019, an area of annually recurring mass stranding events and the location of the original largest known mass stranding of baleen whales in 2015. The results show the power of satellites to deduce the timings of events, which could be vital for long-term monitoring programs.

The international team hope to challenge the current disparity in stranding monitoring efforts through use of satellites. They also call for collaborative partnerships between satellite providers and stranding networks governments and NGOs, for equal access to satellite imagery, a recommendation endorsed by the International Whaling Commission Scientific Committee.

The research highlights the importance of collaborating across remote sensing specialisms to determine if satellites may help understand the environmental and human induced conditions before, during and after a mass stranding event. Other remotely sensed data could help to highlight changes in the ocean environment and to provide an early warning system to mitigate mass stranding events and develop more informed, knowledgeable and rapid response stranding networks.

Moving forward, the team plan to test the robustness of this technology by partnering with existing and efficient stranding networks in hotspot areas, such as New Zealand, to develop working protocols and automated detection procedures. Following this they will concentrate on remote priority locations such as: the Chilean Patagonia region; much of the West and Eastern coastlines of Africa; the Polar Regions; and coasts in politically turbulent regions such as the North West Indian Ocean.

Cetacean strandings from space: Challenges and opportunities of very high resolution satellites for the remote monitoring of cetacean mass strandings by Penny J. Clarke, Hannah C. Cubaynes, Karen A. Stockin, Carlos Olavarria, Asha de Vos, Peter T. Fretwell and Jennifer A. Jackson is published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science. Read the paper on their website

No comments:

Post a Comment