Report provides details of how Trump's appointees got in the way.

JOHN TIMMER - 12/20/2021

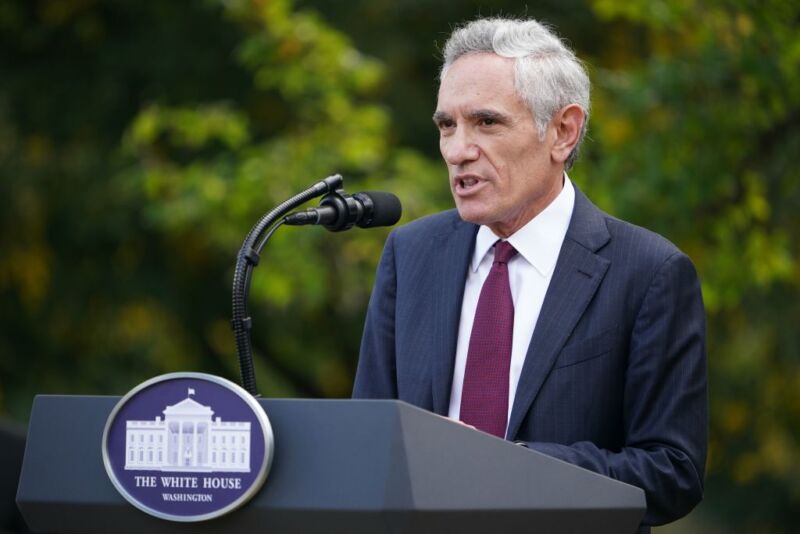

Enlarge / Scott Atlas, a White House adviser, used his position to advocate for allowing the SARS-CoV-2 virus to spread and tried to block testing for it, which would further that goal.

Over the past few months, the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis has been investigating the previous administration's haphazard and sometimes counterproductive response to the pandemic. As testimony was taken and documents were examined, some of the details of the conflicts between politicians and public health would sporadically come out via press releases from subcommittee members. But on Friday the group issued a major report that puts these details all in one place.

The report confirms suspicions about the Trump administration's attempt to manipulate the public narrative about its response, even as its members tried to undercut public health officials. So, while reading may trigger a sense of "I thought we knew this," having it all in one place with the evidence to back it up still provides a valuable function.

Sidelining the CDC

In late February of 2020, just as the pandemic was beginning to pick up in the US, the CDC held a press conference in which Nancy Messonnier issued stark warnings about the potential for COVID-19 to interfere with life in the US. The subcommittee heard testimony that her somber warning angered then-President Trump and, as a result, the CDC was blocked from holding any further press conferences for over three months, during which time the US experienced its first deadly surge of infections.

Later that spring, the CDC attempted to publish guidelines for religious organizations that recommended using masks and suggested the organizations consider suspending choirs and switching to virtual services. That language was altered after intervention by (of all places) the Office of Management and Budget.

By the summer, testing guidance became the target of the administration's ire. In August, the CDC issued bewildering guidelines that suggested that people exposed to those infected by SARS-CoV-2 didn't need to get tested—even though we knew they could easily spread the virus before symptoms started. It took a month for evidence-based guidelines to return. Deborah Birx, who played a major role in the administration's COVID response, testified that the problematic advice was inserted by Scott Atlas, who advocated for allowing the virus to generate immunity by spreading widely. Birx indicated that Atlas changed the language specifically in order to reduce testing and that the attempt to eliminate his interference and restore science-based testing guidelines was opposed by some administration officials.

Birx also confirmed that Atlas and a political appointee named Paul Alexander advocated within the administration for letting the virus spread. Alexander's other claim to fame was attempting to rewrite the CDC's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports in order to make the pandemic seem less alarming. This led CDC Director Robert Redfield to advise CDC staff to delete Alexander's email, which the subcommittee considers an attempt to destroy evidence of political interference.

Beyond the CDC

While the CDC was the primary target of interference, the subcommittee cites other examples. For example, the subcommittee obtained documents indicating that political appointees pushed the FDA to approve hydroxychloroquine, even though there was never any solid scientific evidence that it was effective.

Testimony also indicated that, over a month after declaring a public health emergency, the administration hadn't started working with diagnostic and protective equipment suppliers in order to ensure adequate supplies to manage the pandemic. Once they started obtaining supplies, White House officials would sometimes steer non-competitive contracts to companies with no history of either working with the government or providing medical supplies—including one company that was formed just as the pandemic started.

The evidence gathered by the subcommittee paints a picture of an administration's pandemic response driven by a mix of solid public health advice, political considerations, unscientific personal opinion, and incompetence. Any decision made could be influenced by any number of these factors; the degree to which the latter three were frequently dominant helps explain why the US stumbled so badly in the first year of the pandemic.

JOHN TIMMER

John became Ars Technica's science editor in 2007 after spending 15 years doing biology research at places like Berkeley and Cornell.

No comments:

Post a Comment