Jaw-Dropping Footage from the First Spacecraft to Touch the Sun

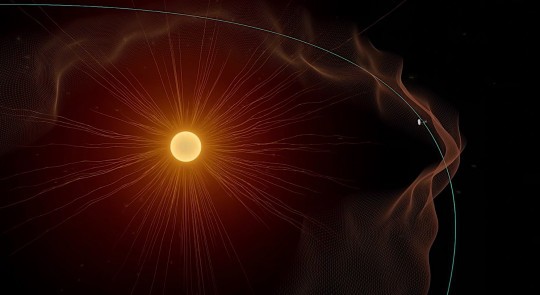

NASA announced this week that its Parker Solar Probe was the first spacecraft to ever “touch the Sun” by flying through its corona, or upper atmosphere. The probe captured the first photos ever from within the corona, and those images were then turned into this incredible 13-second timelapse video.

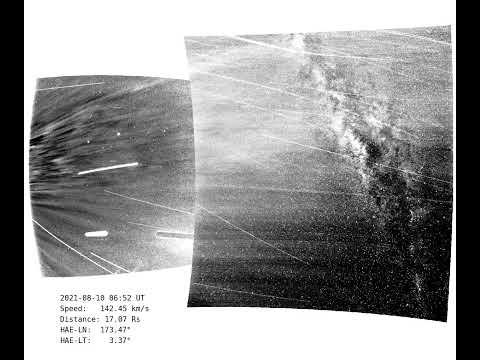

The footage shows what the Parker Solar Probe saw as it passed through the Sun’s corona back in August 2021, flying through structures known as coronal streamers.“These structures can be seen as bright features moving upward and downward in this video compiled from the spacecraft’s WISPR (Wide-field Imager for Parker Solar Probe) instrument,” the JHU Applied Physics Laboratory writes. “Such a view is only possible because the spacecraft flew above and below the streamers inside the corona. Until now, streamers have only been seen from afar.”

These are the same streamers that can be captured from Earth in photos of total solar eclipses.

![]()

“Flying so close to the Sun, Parker Solar Probe now senses conditions in the magnetically dominated layer of the solar atmosphere – the corona – that we never could before,” says Parker project scientist Nour Raouafi. “We see evidence of being in the corona in magnetic field data, solar wind data, and visually in images. We can actually see the spacecraft flying through coronal structures that can be observed during a total solar eclipse.”

The Milky Way can be seen rotating across the frame in the timelapse, but what’s even more incredible is that multiple planets in the Solar System were also captured in the images. There are even views of Earth as seen from within the Sun’s atmosphere.

Here are the features and planets labeled in still frames by astrophysicist Grant Tremblay of the Center for Astrophysics, a collaboration between Harvard and the Smithsonian Institution:

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Parker Solar Probe will continue to make closer and closer approaches to the Sun’s surface over the coming years, and it is likely to enter the Sun’s corona again as early as next month.

“I’m excited to see what Parker Solar Probe finds as it repeatedly passes through the corona in the years to come,” says NASA Heliophysics Division Director Nicky Fox. “The opportunity for new discoveries is boundless.”

Gerry Anderson Primer: Doppelganger/Journey to the Far Side of the Sun

Fastest Spacecraft Ever Made Did (and Didn’t) Touch the Sun, Here’s Why It’s Complicated

The machine, sturdily-made to survive the incredible heat emanating from the star, will eventually get within 3.8 million miles (6.1 million km) from the Sun, reaching speeds of 430,000 miles per hour (692,000 kph), and earning it the title of fastest spacecraft ever made on Earth.

Back in November, Parker was moving at 364,660 miles per hour (586,864 kph), while it was at a distance of 5.3 million miles (8.5 million km) from its target. As it moved closer since then, it prompted NASA into proclaiming it finally touched the Sun.

But what does that mean? Like probably all stars out there, the Sun has no solid surface one can land on, assuming one could survive that. Instead, the flaming ball of gases is comprised of seven layers.

Deep down we have the core, the hottest, densest, and most hellish place in the solar system. Then come the radiative and convection zones at 86,000 miles (138,000 km) from the core, then the photosphere (which is considered the solar surface), the chromosphere, and the transition region.

Last, but not least, comes the corona, the outermost layer of the Sun which starts at about 1,300 miles (2,100 km) above the photosphere. Temperatures there are of at least 900,000 degrees Fahrenheit (500,000 degrees Celsius), the place is invisible with the naked eye and, most importantly, it does not have an upper limit.

And it is this very hard-to-define region that the Parker Solar Probe actually traveled through, at a distance of great many miles from the so-called surface, the photosphere, so those arguing it didn't actually touch the Sun do have a point. For comparison, it’s like a spacecraft passing through the tail of a comet and saying it reached it, or skimming through the upper atmosphere of a planet and claiming the same.

So, in a sense, the Parker Solar Probe did not touch the Sun, it only grazed its fancy clothing.

But, in another sense, it did touch it. You see, the corona has something called the Alfvén critical surface. It is the place that “marks the end of the solar atmosphere and beginning of the solar wind,” and even if it is as elusive as everything else about the Sun, it is generally agreed it comes at anywhere between 4.3 and 8.6 million miles (6.9 to 13.8 million km) from the star.

That, by all accounts, presently puts the Parker past the Alfvén, and right into the Sun’s atmosphere, something that was never done before. And NASA even has proof of that, in the form of the detected magnetic and particle conditions specific to the corona past that point.

Controversy aside, the fact this probe is where it is, and in working order, should benefit us all greatly. Already the machine “sampled particles and magnetic fields there,” and that should “help scientists uncover critical information about our closest star and its influence on the solar system.”

It also proved the Alfvén critical surface isn’t a smooth ball, but an area with spikes and valleys that may influence solar wind and how it eventually impacts us. And, the cherry on the cake, it even moved through something called a pseudostreamer, a loop-like structure we can see from Earth during solar eclipses.

More flybys in this region of space are planned for the future (the next one in January 2022), and they should unlock even more mysteries for us to dissect and marvel at. Untll that time, the first video below shows a stunning recording of the probe’s journey through the corona, as seen from on board Parker.

The second video explains all of the above in easy-to-understand images.

No comments:

Post a Comment