While Washington and Kyiv trade optimism about a possible deal, Russia’s president is signalling to his own people that the war will grind on – and that they should brace for it

Konstantin Eggert

Euractiv

Dec 30, 2025

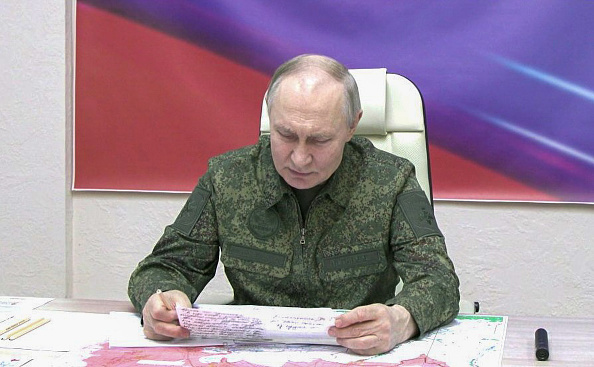

Russian President Vladimir Putin, dressed in military uniform, visited a command post in Kursk, Russia on 12 March 2025 [Photo by Kremlin Press Office / Handout/Anadolu via Getty Images]

The latest round of shuttle diplomacy between Kyiv and Mar-a-Lago has rekindled hopes of a Russia-Ukraine peace deal.

Given that the ultimate decider on peace – Vladimir Putin – wasn’t there, it’s worth taking any declarations of a breakthrough with a healthy pinch of salt. Even as Putin humours Donald Trump and his efforts to broker peace, the Russian has shown little desire to step away from the battlefield.

To understand what really has been on Putin’s mind of late, it’s worth rewinding to his annual staged press conference, which he held just before Christmas.

It was the usual marathon of rehearsed sycophantic questions, approved requests for help from Russia’s far-flung regions (“Vladimir Vladimirovich, the main road in our city of Syktyvkar wasn’t repaired for 15 years!”) and – also quite traditional – unabashed lies by Russia’s dictator.

“It was the West that started the war, we just responded”, he claimed without blinking an eye.

What was missing since the days I attended these events as the BBC Russian Service bureau editor were questions from independent Russian media (none are left inside the country). Veteran BBC correspondent Steve Rosenberg (the real one, not the imposter) asked whether Russia will launch new “special military operations” in the future.

“There won’t be, if you treat us with respect, and respect our interests, just as we’ve always tried to do with you,” Putin replied. “Unless you cheat us, like you did with NATO’s eastward expansion.”

That Russians must be ready for the indefinite continuation of the war was his only recurring message through the whole four hours that the event lasted. There was hardly any mention of peace, even though Kremlin emissary Kirill Dmitriyev was preparing to fly to Miami for the latest peace negotiations as Putin spoke.

What the Russian dictator did was address the Russians’ worries about the state of the economy. For example, he explained in some detail how low economic growth (1%, even officially) was a result of his government’s decision to avoid excessive inflation. Runaway inflation is the perennial nightmare of Russians over 50, who remember the economic turbulence of the 1990s. This group also comprises the majority of his TV audience.

Putin continues to count on their loyalty: after all, ‘saving the country from the Yeltsin-era chaos’ is what they are still supposed to be grateful to him for.

Will he be able to sustain not only the war but the public’s support for it – or at least its benign indifference? The pessimist in me says, yes. Others beg to differ. Researcher Lyubov Tsybulska of Ukraine’s Centre for Strategic Communication and Information Security recently published a convincing analysis of Russia’s depleting manpower resources and gradually decreasing sign-up bonuses for war “volunteers”, i.e. mercenaries.

The report could be dismissed as Ukrainian “infowar” operation – which to some extent it is. But to this former Muskovite, a lot of it sounds rather convincing: the regime’s desire to avoid general mobilisation as a potential factor for political instability; its pronounced unwillingness to conscript people from the well-off and better educated metropolises for the same reason; its attempts to keep recruitment alive without unleashing inflation.

There were two moments during Putin’s press-conference which served as proof of these concealed but gradually growing worries. One was when a specially invited officer, Naran Ochir-Goryayev, recently decorated with the country’s highest award (“Hero of Russia”), told Putin and the audience that “Ukrainians greeted Russians as liberators”, and extolled the virtues of quick-career making in wartime. Ochir-Goryayev (allegedly) climbed from lowly private to first lieutenant in four years of full-scale invasion. If true, I, as former officer myself, have only one explanation: the casualty rate in the Russian army is close to that of the Second World War.

Another episode was truly bizarre. A previously selected and approved caller from the North Caucasus invited Putin to his wedding. Putin responded: “I see you both are 23 and you mentioned you have been together for 8 years. This means you started at 15. It’s good!”

Putin went on to praise the – mostly Muslim – peoples of the North Caucasus for their tradition of very early marriage. Not only does taking child brides contradict the Russian penal code, the practice also violates the convictions of the majority of the population. The Kremlin, however, needs more soldiers.

Recruitment interests dictate the policy. Putin’s strategy: flatter those who can be convinced to sign up (North Caucasus is generally poor and has a strong macho culture) and set an example for others.

Anyone with Russian ears couldn’t help but understand Putin’s real message for “his” people – nothing but war awaits them in the New Year.

Konstantin Eggert is a Russian-born journalist with DW, Germany’s international broadcaster. He is based in Vilnius and was previously editor of the BBC Russian Service Moscow bureau.

The latest round of shuttle diplomacy between Kyiv and Mar-a-Lago has rekindled hopes of a Russia-Ukraine peace deal.

Given that the ultimate decider on peace – Vladimir Putin – wasn’t there, it’s worth taking any declarations of a breakthrough with a healthy pinch of salt. Even as Putin humours Donald Trump and his efforts to broker peace, the Russian has shown little desire to step away from the battlefield.

To understand what really has been on Putin’s mind of late, it’s worth rewinding to his annual staged press conference, which he held just before Christmas.

It was the usual marathon of rehearsed sycophantic questions, approved requests for help from Russia’s far-flung regions (“Vladimir Vladimirovich, the main road in our city of Syktyvkar wasn’t repaired for 15 years!”) and – also quite traditional – unabashed lies by Russia’s dictator.

“It was the West that started the war, we just responded”, he claimed without blinking an eye.

What was missing since the days I attended these events as the BBC Russian Service bureau editor were questions from independent Russian media (none are left inside the country). Veteran BBC correspondent Steve Rosenberg (the real one, not the imposter) asked whether Russia will launch new “special military operations” in the future.

“There won’t be, if you treat us with respect, and respect our interests, just as we’ve always tried to do with you,” Putin replied. “Unless you cheat us, like you did with NATO’s eastward expansion.”

That Russians must be ready for the indefinite continuation of the war was his only recurring message through the whole four hours that the event lasted. There was hardly any mention of peace, even though Kremlin emissary Kirill Dmitriyev was preparing to fly to Miami for the latest peace negotiations as Putin spoke.

What the Russian dictator did was address the Russians’ worries about the state of the economy. For example, he explained in some detail how low economic growth (1%, even officially) was a result of his government’s decision to avoid excessive inflation. Runaway inflation is the perennial nightmare of Russians over 50, who remember the economic turbulence of the 1990s. This group also comprises the majority of his TV audience.

Putin continues to count on their loyalty: after all, ‘saving the country from the Yeltsin-era chaos’ is what they are still supposed to be grateful to him for.

Will he be able to sustain not only the war but the public’s support for it – or at least its benign indifference? The pessimist in me says, yes. Others beg to differ. Researcher Lyubov Tsybulska of Ukraine’s Centre for Strategic Communication and Information Security recently published a convincing analysis of Russia’s depleting manpower resources and gradually decreasing sign-up bonuses for war “volunteers”, i.e. mercenaries.

The report could be dismissed as Ukrainian “infowar” operation – which to some extent it is. But to this former Muskovite, a lot of it sounds rather convincing: the regime’s desire to avoid general mobilisation as a potential factor for political instability; its pronounced unwillingness to conscript people from the well-off and better educated metropolises for the same reason; its attempts to keep recruitment alive without unleashing inflation.

There were two moments during Putin’s press-conference which served as proof of these concealed but gradually growing worries. One was when a specially invited officer, Naran Ochir-Goryayev, recently decorated with the country’s highest award (“Hero of Russia”), told Putin and the audience that “Ukrainians greeted Russians as liberators”, and extolled the virtues of quick-career making in wartime. Ochir-Goryayev (allegedly) climbed from lowly private to first lieutenant in four years of full-scale invasion. If true, I, as former officer myself, have only one explanation: the casualty rate in the Russian army is close to that of the Second World War.

Another episode was truly bizarre. A previously selected and approved caller from the North Caucasus invited Putin to his wedding. Putin responded: “I see you both are 23 and you mentioned you have been together for 8 years. This means you started at 15. It’s good!”

Putin went on to praise the – mostly Muslim – peoples of the North Caucasus for their tradition of very early marriage. Not only does taking child brides contradict the Russian penal code, the practice also violates the convictions of the majority of the population. The Kremlin, however, needs more soldiers.

Recruitment interests dictate the policy. Putin’s strategy: flatter those who can be convinced to sign up (North Caucasus is generally poor and has a strong macho culture) and set an example for others.

Anyone with Russian ears couldn’t help but understand Putin’s real message for “his” people – nothing but war awaits them in the New Year.

Konstantin Eggert is a Russian-born journalist with DW, Germany’s international broadcaster. He is based in Vilnius and was previously editor of the BBC Russian Service Moscow bureau.

Dec 30, 2025

No comments:

Post a Comment