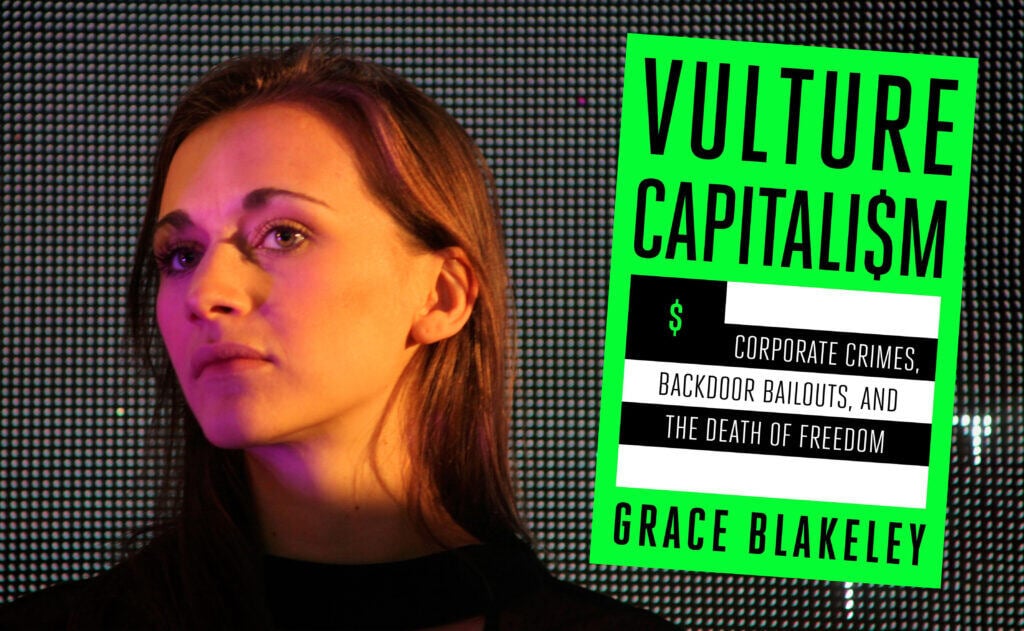

How Capitalism really works – Grace Blakeley’s Vulture Capitalism Review

Vulture Capitalism is, at one level, a really good read, for the scandals that it brings together in one volume – like the Boeing 737 MAX debacle, where the pursuit of profits, lack of regulation, and corporate cost-cutting culture resulted in two crashes that killed hundreds of people, or the ways most of the $800 million allocated by Washington for the Paycheck Protection Plan (PPP) to enable workers to get through the COVID 19 pandemic actually ended up with their employers. Among the direct or indirect beneficiaries of the PPP were House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s husband, Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell’s wife, and Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene, the notorious far-right conspiracy theorist. All owned businesses or were part-owners of enterprises that siphoned off PPP dollars meant for workers.

But don’t get fooled by the title, which was probably the bright idea of the publisher’s marketing department. Vulture Capitalism is not just a muckraking book, a collection of juicy scandals. Where a New York Times investigation ends is where Grace Blakeley really begins her work, which is to “look at how capitalism really looks.” For her, the scandals illustrate not just the doings of corrupt individuals or corporations but the larger, deeper, more encompassing structural corruption that is embedded system of capitalism itself.

Market Versus Plan

Blakeley begins her deconstruction of capitalism by taking up the market-versus-planning debate that continues to animate the economics profession. Neoliberals make out state planning as the greatest enemy of the market, the source of all the inefficiencies, distortions, and screw-ups in what would otherwise be a plain-sailing economic journey. Keynesians say the economy must be managed or “planned” to avoid market failures. Blakeley comes out straightforwardly and declares the debate to be largely a false one. Giant corporations can have a major distorting influence on the market, and their size and resources enable them to plan production not only at a corporate but at a social level. Effective control of the market by a few giants allows them to do large-scale planning even as they compete with each other.

Blakeley is refreshingly an unapologetic Marxist, and Marx could not have articulated his insights on the relationship between the market and planning for a contemporary audience better than her:

Capitalism is a system defined by a tension—a dialectic—between markets and planning, in which some actors are better able to exert control over the system than others, but in which no one actor—let alone individual—can control the dynamics of production and exchange entirely. Capitalism is a system that teeters on the knife edge between competition and coordination; this tension is what explains both its adaptability and rigid inequalities.

So, the real conflict is not between markets and planning, but the ends of planning, with accumulating profit being the goal of planning under capitalism, and—in theory at least—the general interest being the aim of socialist planning.

Making Economics Accessible

Blakeley does not introduce a new theory about the way capitalism works. “Most of the ideas discussed in this book are not new,” she tells us right from the beginning. “My argument is constructed based on the analysis of the work of well-known economists, with which academic readers will already be familiar.” She wants to make their ideas accessible to people. Given the well-deserved reputation of orthodox economics being the contemporary equivalent of the medieval theological preoccupation with how many angels could stand on the head of a pin, this task is not to be sneered at, since the alternative that many opt for is conspiracy theory, which is the default mode of analysis in populist circles on both the Left and the Right.

But making economic theories accessible does not mean making their ideas sound simplistic. Even when it comes to economists Blakeley disagrees with, like Friedrich Hayek, Ronald Coase, and Joseph Schumpeter, she is not dismissive and accords their views the critical analysis they deserve.

In the case of Schumpeter, for instance, the notion of the process of “creative destruction” destroying monopolies may have once been a powerful reflection of the dynamics of early twentieth-century capitalism. But it is a theory that has outlived its usefulness, Blakeley contends, because today’s corporations, with their massive assets, can control the process of technological innovation, buying out or stifling the growth of innovative corporations that may threaten their stranglehold on the market.

Blakeley brings aboard not only political economists to help us understand the dynamics of contemporary capitalism. She draws on the insights of the French thinker Michel Foucault to show that neoliberalism not only seeks to shape the economy but the personalities of people as well. Foucault pointed to the creation of the entrepreneurial self or homo economicus who is engaged mainly in terms of maximizing his self-interest. This self-conceptualization has the effect of undermining the possibility of collective action, resulting in the “destruction of society itself, and its replacement with a structured competition between individual human capitals—but on a fundamentally unequal playing field.”

The State under Capitalism

According to neoliberals, the contradiction between market and planning is a manifestation of the larger conflict between the market and state as the principal organizing principle of the economy. The reality is that both the market and the state serve the interest of capital. For the most part, this is not done in a direct, instrumental fashion like extending benefits and perks to individual capitalists, though there is no lack of cases where government contracts or legislation favors particular business interests, as the cases of Boeing and the PPP debacle illustrate. More important is the fact that the state pursues the “general” and “long-run interest” of the capitalist class. Instead of conceiving the state as an instrument of the capitalist class, one must see the state as an institution or set of structured relations that “organize capitalists into a coherent group, conscious of its interests and able to enact them.”

Blakeley is expressing here the view articulated by the French philosopher Louis Althusser, the Greek-French political economist Nicos Poulantzas, and the American political sociologist James O’Connor: that the state is characterized by its “relative autonomy” from economic power relations because its primal role is to stabilize a mode of production that is marked by sharp social contradictions. Perhaps the best conceptualization of this relationship between the political and the economic was provided by O’Connor who saw the relative autonomy of the state as stemming from the tension between its two functions: that is, it has to balance the needs of capital accumulation that increases the profits of the capitalist class and the system’s need for legitimacy to maintain stability. Welfare spending by the state may cut into capital accumulation, but it is necessary to create political stability. This tension gives rise to a stratum of technocrats to manage the tradeoffs between the two primordial drives of capital accumulation and legitimation. Management of this tension, which expressed itself in, among others, the trade-off between inflation and unemployment, was erected into a “science” by the followers of John Maynard Keynes, but this drew the ire of Hayek and his followers, who regarded the Keynesians tinkering with the market as courting economic inefficiency and subverting political freedom.

But Blakeley puts things in perspective. Keynes’s technocrats may engage in social spending but the purpose is to keep the system stable and preserve the class division between those who benefit from the system because they own the means of production and those who are exploited by it despite their being the beneficiaries of some crumbs from social spending. Proponents of reform capitalism were elated by the massive government stimulus programs during the Covid 19 pandemic, but, as in the case of the PPP—where workers received one dollar for every four allocated by the program, with the rest going to business owners like the Trump fanatic Marjorie Taylor Greene—it was the corporate elite and its allied upper middle entrepreneurial and professional strata that cornered most of the benefits of the U.S. government’s fiscal spending and monetary easing policies.

Needed: Another Book

Vulture Capitalism focuses on the class division between owners and workers central to capitalism and its ramifications throughout the system. There are, however, key dimensions of capitalism that Blakely does not tackle but which are central to understanding how it operates. Among these are the social reproduction of the system, where gender inequality and patriarchal oppression play a decisive role, and the way racism stratifies and differentiates the working class, providing what the great sociologist W.E.B. Dubois called a “psychological wage” that coopts white workers into supporting the system. But there is only so much one can pack into as single volume, so it can only be hoped that Blakeley will come out with another volume that will bring to these and related issues the same clearsighted analysis and engaging style she displays in her current book.

Also deserving of further analysis is democratic planning. The final section of the book presents us with examples of exciting possibilities for progressive planning, such as the detailed plan proposed by the workers of Lucas Aerospace Corporation to turn this British arms manufacturer into a producer of socially useful commodities and the innovative “participatory budgeting” formulated by the city government of Porto Alegre that spread to over 250 other cities in Brazil. Blakeley’s discussion of various democratic and socialist initiatives is a valuable complement to the late sociologist Erik Olin Wright’s book Envisioning Real Utopias.

It would have been useful, however, for Blakeley to draw out lessons from the failure of central planning in the Soviet Union and how democratic planning would be different, since many people associate socialist planning with the Soviet Union. Here, it would also be important to contrast Soviet central planning with Chinese planning, which allowed market forces to develop non-strategic sectors of the economy while restricting foreign investment in sectors considered strategic and prioritizing the transfer of technology from transnational corporations to key industries. True, there are some major problems with China’s technocratic development model, but an annual growth rate of 10 percent over 30 years and the radical reduction of poverty to two percent of the population (according to the World Bank) is not to be ignored, even by partisans of democratic planning, especially since, despite its technocratic bias, the “Chinese Model” is finding so many partisans in the Global South. Indeed, what else can one take away from the Biden administration’s adoption of industrial policy in its effort to catch up with China except Washington’s moving away from neoliberalism and the triumph of planning?

Again, you can only pack so many topics into one volume, but I raise these concerns related to democratic planning in the hope that, whether in articles or in books, Grace Blakeley will apply to them the same analytical acuity and clear exposition she has displayed in analyzing class conflict, the market, and the state in Vulture Capitalism.

- You can grab a copy of Grace’s new book ‘Vulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts and the Death of Freedom‘

- You can follow Grace Blakeley on Facebook, Twitter/X and Instagram.

- This article was originally published by Foreign Policy in Focus on June 17th, 2024.

Forget free markets – it’s all about global domination!

Mike Phipps reviews Vulture capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts and the Death of Freedom, by Grace Blakeley, published by Bloomsbury.

In the Introduction to this book, Grace Blakeley says her aim is to show that “capitalism is not defined by the presence of free markets, but by the rule of capital; and that socialism is not defined by the dominance of the state over all areas of life, but by true democracy.” How far does she succeed?

The first premise is amply illustrated – from the huge sums of government money thrown at the under-regulated and cost-cutting American aviation industry, to the state bailouts for the US car industry which allowed Ford and others to continue to pay huge dividends to shareholders. Embracing neoliberalism has certainly not resulted in a smaller state: what has changed under its system is who benefits.

Pandemic piñata

The Covid pandemic underlines this. The US’s “Paycheck Protection Program” saw workers receive just $1 out of every $4 distributed through the initiative. The rest went to business and has mostly never been repaid. Many of the companies involved use tax havens to cut their tax bills. Several members of Congress benefited financially from the scheme, as did lobbyists. Meanwhile, millions of workers lost their jobs or were evicted by companies that received public money.

Likewise in the UK, “dozens of large companies that had accessed government support through the Bank of England’s Covid Corporate Financing Facility went on to lay off workers and pay out dividends to shareholders.”

Similarly, all of France’s top companies received some form of government support and paid out 34 billion euros to shareholders while cutting 60,000 jobs around the world. A recent report noted that “public assistance to the private sector now exceeds the amount paid out in social welfare.”

In Australia, a colossal A$12.5 billion of government money was given to companies that were “largely unaffected “ by the pandemic. All over the world, the same picture emerges.

The precedent for such largesse was set during the financial collapse of 2008. Although the crash is often blamed on corporate greed, in reality the investment banks would never have taken the risks they did without the implicit insurance of the central bank, and behind it the government. The crisis’s global dimension “was driven as much by crooked coordination between powerful actors as it was by unrestrained ‘free market’ capitalism. And when the crisis did hit, once again the state stepped in to shield powerful vested interests from the consequences of their own greed.” Prosecutions in its wake were almost unheard of.

Permanent subsidies and rigged rules

Big corporations expect a government bailout in a crisis, but for many industries public subsidies are a permanent state of affairs. The fossil fuel industry gets a staggering $5.9 trillion of public money worldwide.

In the world of exports, ‘free markets’ don’t really explain the dominance of the companies of the Global North over poorer countries, for all the neoliberal rhetoric about free trade. Attempts by the Global South to use industrialization to escape the cycle of dependency enshrined in their export of raw materials, have repeatedly been thwarted by richer countries, whether by direct political interference – as in the US-sponsored coup in Guatemala in the 1950s – or through Western-imposed trade rules. These prevent governments in poorer countries from protecting their fledgling industries against Western imports, themselves often state-subsidised.

Investor-state dispute settlements (ISDSs) are part of this international architecture, dreamed up – and arguably rigged – by the West. When after a lengthy legal battle, the Ecuadorian courts ordered Chevron to pay $9.5 billion in compensation for a massive toxic waste spillage in the country’s rainforest, the company closed all its Ecuadorian operations and launched an ISDS claim, which overturned the judgment. To add insult to injury, the Ecuadorian government was then ordered to pay $800 million of the company’s legal costs.

Blakeley concludes: “ISDSs are part of a growing body of international law that, with the active support of powerful states, has helped to routinise corporate crime on a mass scale.” They can be used to get compensation for companies whenever a government passes a law to discourage smoking or protect the environment. Canada, Mexico and Germany have all been forced to abandon or dilute environmental regulations and pay compensation to corporate polluters in recent years.

And this is just one mechanism that allows Western capital to penetrate overseas markets on unequal terms. The state-assisted exploitation of less developed countries can be violent and barbarous. “One of the first things the US government did with occupied Iraq was sell off state assets en masse. In doing so, the planners of the 2003 US invasion sought to share the spoils of the invasion with US businesses and introduce the disciplining hand of American capital into Iraqi society.”

Blakeley is hardly the first economist to highlight capitalism’s monopolistic tendencies. But what’s new here is how today’s giant companies use their privileged position not just to corner the market or raise prices, but to establish for themselves as much sovereignty as possible. This applies not just internally, for example in the case of Amazon’s ruthless approach to suppressing trade union organisation, but also externally, as with corporations involved internationally in human rights abuses.

In this sense, modern corporations constitute a form of private government, hierarchically centralised and controlled, and often unconstrained by the national laws of weak governments – in poorer countries especially, but not exclusively. And in many fields, such companies are empowered to act using force – from private armies to outsourced contracts for immigration detention and removal activities.

Democratic alternatives

Blakeley’s focus on economic democracy as an expression of nascent socialism is a lot shorter. The 1976 Alternative Plan for Lucas Aerospace was a significant milestone, but it may be overstating its importance to say “it provided inspiration for workers all over the world for the next several decades.” In any case, as one reviewer pointed out, “it was swatted aside by management.”

However, the author does produce some interesting examples of human cooperation and democratic planning: the New South Wales Builders Labourers Federation which refused to allow its labour to be used for harmful purposes; the Union of Farm Workers’ occupation of land in Andalusia after the death of the fascist dictator Franco in 1975; the Brazilian Workers Party’s experiment in participatory budgeting pioneered in Porto Alegre in 1989, which spread to over 250 cities in Brazil and another 1,500 around the world; the People’s Plan in the Indian state of Kerala in 1996; the post-2008 Better Reykjavik initiative in which 40,000 people pitched ideas to improve Iceland’s capital in an online consultation; the Preston Council experiment in Community Wealth Building; and quite a few others. While the levels of genuine popular participation in these experiments vary considerably and most proved short-lived, they do demonstrate the potential of this kind of democratic planning.

For Blakeley, the 1970-3 Popular Unity government in Chile showed that “it is possible to begin building democratic institutions at scale.” However, it also underlined that full control of the state apparatus is vital, to prevent not just capital strikes and flight, but also the possibility of a violent military coup of the kind that toppled Allende.

Democratising society through activity in trade unions and community campaigns falls some way short of this critical goal. The author’s section on “Democratise the state” says nothing about dismantling its repressive apparatus.

Vulture Capitalism is certainly worth reading for its well-argued critique of contemporary capitalism and the historical alternatives it explores. However, as with many books in this vein, how we proceed from the current mess to a more enduring socialist alternative is less clear.

Mike Phipps’ book Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow: The Labour Party after Jeremy Corbyn (OR Books, 2022) can be ordered here.