TECHNO MYTHOS

Is nuclear fusion the 'hottest' new renewable on the block?

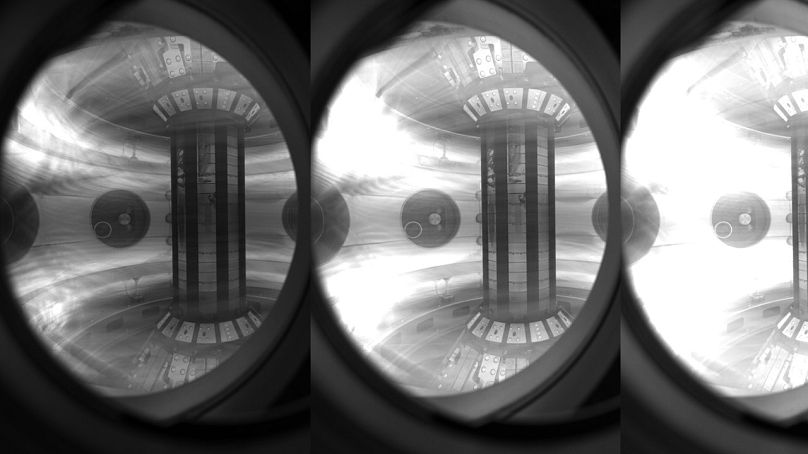

Tokamak Energy's reactor could be where nuclear fusion first occurs. - Copyright Tokamak Energy

By Lottie Limb • Updated: 13/12/2021 - 16:59

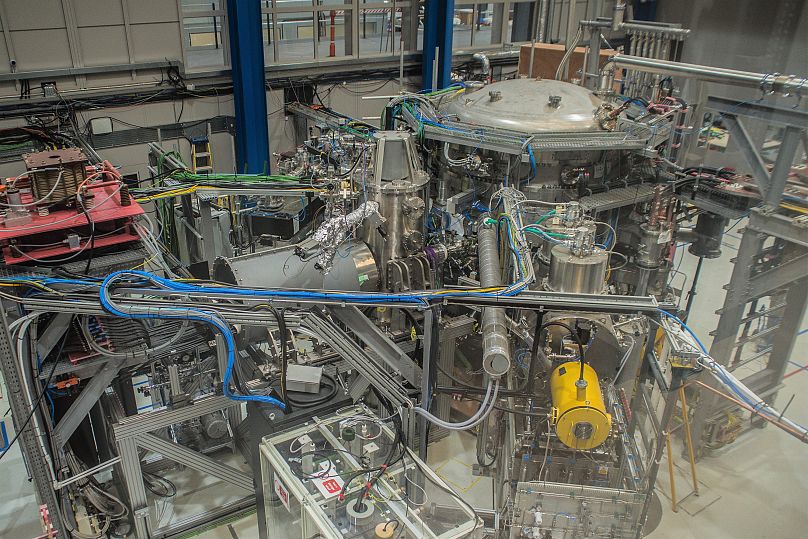

A small railway town in southern England could go down in history as the place where nuclear fusion kicked off.

The reaction process - which would generate vast amounts of low-carbon energy - has evaded scientists for decades, but a private company in Didcot, Oxfordshire says it’s now a question of if, not when.

Tokamak Energy is firing its nuclear reactor up to 50 million degrees celsius - almost twice the core temperature of the sun. By shooting 140,000 amps of electricity into a cloud of hydrogen gas, the team are trying to force hydrogen atoms to fuse, thereby creating helium.

These fusion forces are the same ones that power the sun. While there’s no danger that Didcot could become the new centre of the solar system, the industrial estate could spark the start of a cheap, clean energy supply.

Nuclear fusion poses huge technical challenges.

Tokamak Energy

“We will crack it,” CEO Chris Kelsall told the BBC on a recent trip, “the answer is out there right now with Mother Nature as we speak. What we have to do is find that key and unlock the safe to that solution. It will be found.”

Having ramped the temperature up to mind-boggling degrees, the experiment’s next step is to see if nuclear fusion can produce more energy than it uses.

“We will crack it,” CEO Chris Kelsall told the BBC on a recent trip, “the answer is out there right now with Mother Nature as we speak. What we have to do is find that key and unlock the safe to that solution. It will be found.”

Having ramped the temperature up to mind-boggling degrees, the experiment’s next step is to see if nuclear fusion can produce more energy than it uses.

Is nuclear fusion safe?

In case it rings alarm bells to anyone in the vicinity, nuclear fusion is very different from nuclear fission and its associated disasters

The process occurs inside a ‘tokamak’ - a device which uses a powerful magnetic field to contain the swirling cloud of hydrogen gas. This stops the superheated plasma from touching the edge of the vessel, as it would otherwise melt anything it comes into contact with.

If anything goes wrong inside a fusion reactor, the device just stops - so there’s no risk of this astronomical heat being unleashed.

Magnetic fields trap the electrically-charged plasma particles in an 'apple-core' shape, keeping the fusion fuels contained and hot.

Tokamak Energy

The plasma has to be heated to 10 times the temperature of the sun to get it going, and is capable of fusing two hydrogen nuclei into a helium nucleus.

Nuclear fission, on the other hand, is the dangerous kind. This creates energy by splitting one ‘heavy’ atom (typically uranium) into two. This breakdown generates a large amount of radioactive waste in the process, which remains hazardous for years.

Fusion cannot produce a runaway chain reaction, like the one that happened at Chernobyl in 1986, so no exclusion zone is needed around Milton Park, Didcot, where the reactor is based.

Laura Hussey, an editor who works minutes away at a publishing office on the business park, says she is “really encouraged to hear how safe it is and really happy to see this big investment in clean energy.”

The plasma has to be heated to 10 times the temperature of the sun to get it going, and is capable of fusing two hydrogen nuclei into a helium nucleus.

Nuclear fission, on the other hand, is the dangerous kind. This creates energy by splitting one ‘heavy’ atom (typically uranium) into two. This breakdown generates a large amount of radioactive waste in the process, which remains hazardous for years.

Fusion cannot produce a runaway chain reaction, like the one that happened at Chernobyl in 1986, so no exclusion zone is needed around Milton Park, Didcot, where the reactor is based.

Laura Hussey, an editor who works minutes away at a publishing office on the business park, says she is “really encouraged to hear how safe it is and really happy to see this big investment in clean energy.”

The nuclear fusion reactor shares the park with a number of other businesses.

Tokamak Energy

When will nuclear fusion become a viable source of energy?

It’s a question that scientists have been asking themselves (and have been asked by journalists) for decades. “It’s difficult,” Tokamak Energy physicist Dr Hannah Willett says, while explaining that “[we] get a lot more energy out of this reaction than out of just burning fossil fuels.”

If successful, the experiment could see a constellation of tiny suns created on Earth. Fusion energy would be a major pathway in the green transition - alongside natural sources like solar, wind and tidal. The hydrogen can be derived from seawater, meaning we have a virtually limitless supply of fuel.

Scientists have been trying to make fusion work for more than 50 years and it could still be a while before we can effectively power our homes using it.

It’s a question that scientists have been asking themselves (and have been asked by journalists) for decades. “It’s difficult,” Tokamak Energy physicist Dr Hannah Willett says, while explaining that “[we] get a lot more energy out of this reaction than out of just burning fossil fuels.”

If successful, the experiment could see a constellation of tiny suns created on Earth. Fusion energy would be a major pathway in the green transition - alongside natural sources like solar, wind and tidal. The hydrogen can be derived from seawater, meaning we have a virtually limitless supply of fuel.

Scientists have been trying to make fusion work for more than 50 years and it could still be a while before we can effectively power our homes using it.

Once fusion power is achieved, the scalable technology could be rolled out across the world

Tokamak Energy

But as governments get more serious about renewable power - with the UK investing £10 million (€11.7 million) into Tokamak Energy last year, Kelsall’s “key” feels increasingly within reach.

Meanwhile five locations in Scotland and England have been shortlisted as the potential future home of the UK’s prototype fusion energy plant - the Spherical Tokamak for Energy Production (STEP) - with a decision due around the end of 2022.

Scientists hope the power station can be wired into the national electricity grid - eventually providing energy for people’s homes, and a template to be replicated around the world.

But as governments get more serious about renewable power - with the UK investing £10 million (€11.7 million) into Tokamak Energy last year, Kelsall’s “key” feels increasingly within reach.

Meanwhile five locations in Scotland and England have been shortlisted as the potential future home of the UK’s prototype fusion energy plant - the Spherical Tokamak for Energy Production (STEP) - with a decision due around the end of 2022.

Scientists hope the power station can be wired into the national electricity grid - eventually providing energy for people’s homes, and a template to be replicated around the world.

Is nuclear fusion finally for real?

Some very rich people seem to think so.

James Pethokoukis, Columnist

December 3, 2021·

Fusion. Illustrated | iStock

America's first Atomic Age ended on March 28, 1979, with the partial meltdown of the Three Mile Island Unit 2 reactor, near Middletown, Pennsylvania. Despite the negligible radiation release, the accident led to canceled projects, industry bankruptcies, and a further public souring on nuclear energy. Nuclear's share of U.S. electricity production has been flat, around 20 percent, for decades.

But the dreams of the most optimistic nuclear proponents were always far bigger than an America dotted with fission reactors, where power is produced by the controlled splitting of uranium atoms. Eventually, fission would be replaced by fusion, the melding of hydrogen isotopes which produces more — much more — energy than it consumes. Then we would have energy's Holy Grail: pollution-free power produced using common (and therefore cheap) elements like hydrogen. No carbon emissions, no long-lived radioactive waste. All we have to do is solve one of the trickiest engineering problems in human history: recreating the sun here on Earth.

That project has been stalled by long years of technical frustration. But now, some of the world's richest people are betting the fusion problem might be solvable sooner rather than later. Earlier this week, Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), a startup spun off from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said it had raised nearly $2 billion in private investment, including from mega-billionaires Bill Gates and George Soros. This is the biggest bet on fusion so far, even amid record funding for some two other dozen startups.

The CFS haul doubles the investor dough devoted to those firms, and that includes the previous record of $500 million invested early last month into Helion, a startup backed by well-known tech investors Sam Altman and Peter Thiel. As for CFS, CEO Bob Mumgaard said the new investment would allow it to demonstrate a net-energy fusion reactor by 2025 as well as begin work on the first commercial fusion power plant by the early 2030s.

Replacing dirty fossil fuels with clean power doesn't fully capture the potential of nuclear fusion. Clean, cheap, abundant energy could, for instance, help produce hydrogen for fuel, power giant machines to pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and desalinate water on a large scale. No longer would concerns about energy and climate change limit our aspirations, even if they just involve energy-intensive Bitcoin mining.

And that's just here on Earth. While one could make an argument in favor of other emerging power sources — including advanced fission, enhanced geothermal, even space-based solar power — fusion would be especially helpful if humanity is going to become a space-faring civilization. As physicist Arthur Turrell, author of The Star Builders: Nuclear Fusion and the Race to Power the Planet, told me in a recent interview: "If you look at what realistic trips outside of our kind of solar system's backyard would have to be powered by — or even the Earth's backyard, I should say — fusion is one of the best candidates for that, because it packs a lot of energy into a very small amount of space."

Critics point to past hype cycles and failure, which is totally fair. But the level of private interest, in addition to recent technical advances, should give special reason for hope this time around. Hard-headed, results-oriented investors are sinking big money into the sector because they really think breakthroughs are imminent in a way they haven't been before. Maybe, a decade from now, the world's first $3 trillion company will be a fusion company rather than an online retailer or social media platform.

Moreover, this wouldn't be the first time a long-gestating energy technology suddenly burst on the scene and changed everything. The recent surge in gasoline prices has some politicians recalling the 1970s energy shocks. But there's a more recent example of an energy price spike, although many of us seem to have forgotten it.

A combination of strong demand and stagnant production caused an oil shock in 2007 and 2008, with oil prices hitting a record high of $145 a barrel on July 3, 2008. It was a great time for books and blogs about "peak oil" and how the world was running out of cheap fossil fuels. But then the global financial crisis crushed economies and demand while the "shale revolution" — the combo of hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling — simultaneously came into its own. The U.S. significantly increased domestic oil and natural gas production. We innovated our way out of peak oil.

But there are no guarantees fusion will follow that pattern. Sometimes the smart money gets it wrong. The artificial intelligence sector is famous for its boom and busts (also known as "AI winter") where interest soars and investor cash floods in — and then floods out again when the tech fails to deliver. Where are all the self-driving cars that were supposed to be on American roads by now?

The same could happen with fusion. Yet compared to the odds of humans dealing with climate change by consuming less and accepting a slower increase (or even a decline) in living standards, the chances for an Age of Fusion look pretty good.

James Pethokoukis, Columnist

December 3, 2021·

Fusion. Illustrated | iStock

America's first Atomic Age ended on March 28, 1979, with the partial meltdown of the Three Mile Island Unit 2 reactor, near Middletown, Pennsylvania. Despite the negligible radiation release, the accident led to canceled projects, industry bankruptcies, and a further public souring on nuclear energy. Nuclear's share of U.S. electricity production has been flat, around 20 percent, for decades.

But the dreams of the most optimistic nuclear proponents were always far bigger than an America dotted with fission reactors, where power is produced by the controlled splitting of uranium atoms. Eventually, fission would be replaced by fusion, the melding of hydrogen isotopes which produces more — much more — energy than it consumes. Then we would have energy's Holy Grail: pollution-free power produced using common (and therefore cheap) elements like hydrogen. No carbon emissions, no long-lived radioactive waste. All we have to do is solve one of the trickiest engineering problems in human history: recreating the sun here on Earth.

That project has been stalled by long years of technical frustration. But now, some of the world's richest people are betting the fusion problem might be solvable sooner rather than later. Earlier this week, Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), a startup spun off from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said it had raised nearly $2 billion in private investment, including from mega-billionaires Bill Gates and George Soros. This is the biggest bet on fusion so far, even amid record funding for some two other dozen startups.

The CFS haul doubles the investor dough devoted to those firms, and that includes the previous record of $500 million invested early last month into Helion, a startup backed by well-known tech investors Sam Altman and Peter Thiel. As for CFS, CEO Bob Mumgaard said the new investment would allow it to demonstrate a net-energy fusion reactor by 2025 as well as begin work on the first commercial fusion power plant by the early 2030s.

Replacing dirty fossil fuels with clean power doesn't fully capture the potential of nuclear fusion. Clean, cheap, abundant energy could, for instance, help produce hydrogen for fuel, power giant machines to pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and desalinate water on a large scale. No longer would concerns about energy and climate change limit our aspirations, even if they just involve energy-intensive Bitcoin mining.

And that's just here on Earth. While one could make an argument in favor of other emerging power sources — including advanced fission, enhanced geothermal, even space-based solar power — fusion would be especially helpful if humanity is going to become a space-faring civilization. As physicist Arthur Turrell, author of The Star Builders: Nuclear Fusion and the Race to Power the Planet, told me in a recent interview: "If you look at what realistic trips outside of our kind of solar system's backyard would have to be powered by — or even the Earth's backyard, I should say — fusion is one of the best candidates for that, because it packs a lot of energy into a very small amount of space."

Critics point to past hype cycles and failure, which is totally fair. But the level of private interest, in addition to recent technical advances, should give special reason for hope this time around. Hard-headed, results-oriented investors are sinking big money into the sector because they really think breakthroughs are imminent in a way they haven't been before. Maybe, a decade from now, the world's first $3 trillion company will be a fusion company rather than an online retailer or social media platform.

Moreover, this wouldn't be the first time a long-gestating energy technology suddenly burst on the scene and changed everything. The recent surge in gasoline prices has some politicians recalling the 1970s energy shocks. But there's a more recent example of an energy price spike, although many of us seem to have forgotten it.

A combination of strong demand and stagnant production caused an oil shock in 2007 and 2008, with oil prices hitting a record high of $145 a barrel on July 3, 2008. It was a great time for books and blogs about "peak oil" and how the world was running out of cheap fossil fuels. But then the global financial crisis crushed economies and demand while the "shale revolution" — the combo of hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling — simultaneously came into its own. The U.S. significantly increased domestic oil and natural gas production. We innovated our way out of peak oil.

But there are no guarantees fusion will follow that pattern. Sometimes the smart money gets it wrong. The artificial intelligence sector is famous for its boom and busts (also known as "AI winter") where interest soars and investor cash floods in — and then floods out again when the tech fails to deliver. Where are all the self-driving cars that were supposed to be on American roads by now?

The same could happen with fusion. Yet compared to the odds of humans dealing with climate change by consuming less and accepting a slower increase (or even a decline) in living standards, the chances for an Age of Fusion look pretty good.

No comments:

Post a Comment