Tierra del Fuego, the remote South American island now divided between Chile and Argentina, was home to peoples such as the Selk’nam for 10,000 years.

Photograph: Age Fotostock/Alamy

History books said the Selk’nam, inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego at the southern tip of South America, were extinct but Chile may be about to legally recognize their descendants

Mat Youkee in Tierra del Fuego

@matyoukeeTue 3 May 2022

One of José Vásquez Chogue’s enduring childhood memories is that of his grandfather on the doorstep of his home in the Chilean capital, Santiago, staring at the night sky. “He would always face south,” Vásquez recalled. “He would point out the Southern Cross and show me the stars which represent our ancestors.”

‘For our grandchildren’: the man recording the lives of Paraguay’s vanishing forest people

The older man had grown up on a frozen and remote island in Patagonia and was a member of the Selk’nam tribe. But Chilean history books had declared the people extinct. When José, captivated by the anthropological displays of Chile’s National History Museum, tried to explain his bloodline to a member of staff he was met with derision. “I told him that they were my people, but he didn’t believe me. We were taught at school that all our brothers were all dead.”

The redrafting of Chile’s constitution has created the opportunity to set the history books straight. After Vásquez made an impassioned intervention at the constitutional convention in August, the government released funds for an anthropological, historiographic and archeological study of the Selk’nam. The results of that study, released earlier this month, acknowledged the continued existence of the people and called for their legal recognition.

“The Selk’nam people are not extinct, they are currently in a process of cultural reappropriation and recreation, and they have the right to reconstruct their own [historical] memory,” said Karla Rubilar, the minister of social development.

History books said the Selk’nam, inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego at the southern tip of South America, were extinct but Chile may be about to legally recognize their descendants

Mat Youkee in Tierra del Fuego

@matyoukeeTue 3 May 2022

One of José Vásquez Chogue’s enduring childhood memories is that of his grandfather on the doorstep of his home in the Chilean capital, Santiago, staring at the night sky. “He would always face south,” Vásquez recalled. “He would point out the Southern Cross and show me the stars which represent our ancestors.”

‘For our grandchildren’: the man recording the lives of Paraguay’s vanishing forest people

The older man had grown up on a frozen and remote island in Patagonia and was a member of the Selk’nam tribe. But Chilean history books had declared the people extinct. When José, captivated by the anthropological displays of Chile’s National History Museum, tried to explain his bloodline to a member of staff he was met with derision. “I told him that they were my people, but he didn’t believe me. We were taught at school that all our brothers were all dead.”

The redrafting of Chile’s constitution has created the opportunity to set the history books straight. After Vásquez made an impassioned intervention at the constitutional convention in August, the government released funds for an anthropological, historiographic and archeological study of the Selk’nam. The results of that study, released earlier this month, acknowledged the continued existence of the people and called for their legal recognition.

“The Selk’nam people are not extinct, they are currently in a process of cultural reappropriation and recreation, and they have the right to reconstruct their own [historical] memory,” said Karla Rubilar, the minister of social development.

People of the Selk’nam tribe wearing furs, circa 1890-1900.

Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

If, in the months ahead, the government of Gabriel Boric legally recognizes the Selk’nam, they could be eligible for land and legislative representation. But more important for Vásquez would be the recognition of the crimes committed against his ancestors.

“It’s important that the history of our people and the truth come to light, so people know what happened to the Selk’nam and the other Indigenous peoples in Chile,” he says.

When Ferdinand Magellan rounded the southern tip of South America in 1520, it was the campfires of Indigenous tribes, burning on the hillside, that gave the region its name: Tierra del Fuego (Land of Fire). The main island – now split between Chile and Argentina – and the surrounding archipelago had been inhabited for over 10,000 years by hunter-gatherer peoples feeding on shellfish, berries and guanaco, a relative of the llama.

If, in the months ahead, the government of Gabriel Boric legally recognizes the Selk’nam, they could be eligible for land and legislative representation. But more important for Vásquez would be the recognition of the crimes committed against his ancestors.

“It’s important that the history of our people and the truth come to light, so people know what happened to the Selk’nam and the other Indigenous peoples in Chile,” he says.

When Ferdinand Magellan rounded the southern tip of South America in 1520, it was the campfires of Indigenous tribes, burning on the hillside, that gave the region its name: Tierra del Fuego (Land of Fire). The main island – now split between Chile and Argentina – and the surrounding archipelago had been inhabited for over 10,000 years by hunter-gatherer peoples feeding on shellfish, berries and guanaco, a relative of the llama.

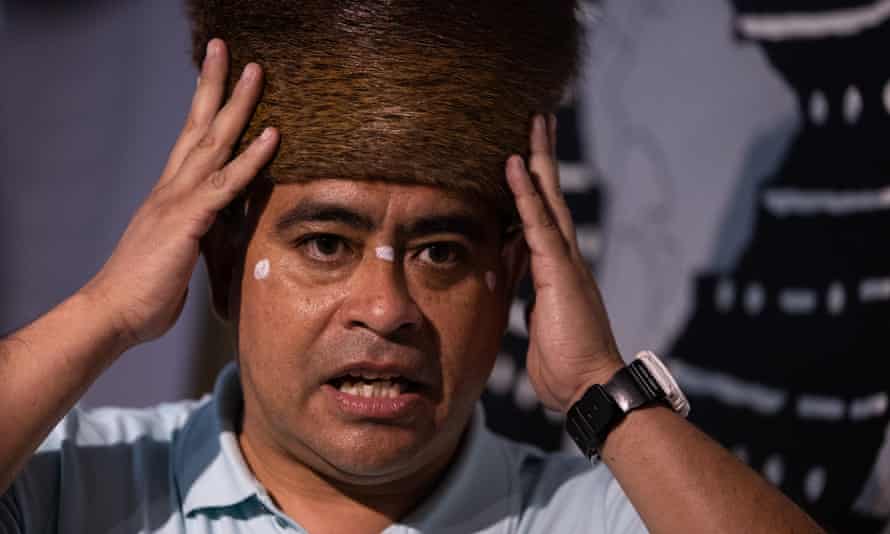

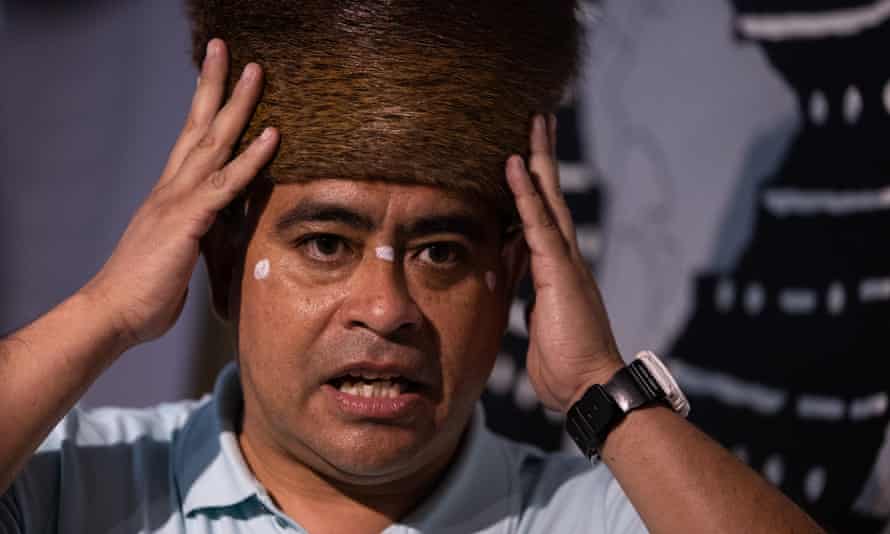

Jose Vásquez: ‘It’s important that the history of our people and the truth come to light.’ Photograph: Alberto Valdés/EPA

Subsequent European exploration left a legacy of bleak place names – Port Famine, Useless Bay, Tortuous Passage – but the newcomers had limited contact with Indigenous people.

In November 1886 Ramón Lista, an Argentinian explorer landed on the windswept and barren shores of the Bay of San Sebastián in Tierra del Fuego. By his own account, lacking the resources to take them prisoner, he ordered his accompanying soldiers to shoot 28 Selk’nam, including women and children, that they encountered there.

In the following 40 years Argentinian and Chilean ranchers and miners would exterminate thousands of Selk’nam, dispatch others to German human zoos, and send many more to Salesian Christian missions where they frequently succumbed to disease. The last known full-blood Selk’nam died in 1974.

Indigenous Chileans defend their land against loggers with radical tactics

On the Argentinian side of Tierra del Fuego, the Selk’nam of the maternal line have been recognized by law since 1994 and 36,000 hectares provided to the community as ancestral lands. Last year 25 November - the anniversary of the massacre perpetrated by Lista - was recognized as the Day of the Selk’nam Genocide and flags were flown at half-mast.

“The Argentinian state came to exterminate, it was a genocide and now it is a day of mourning” says Vanina Ojeda, a Selk’nam who is now secretary of Original Peoples for Tierra del Fuego. “For years the state tried to make invisible the crimes of the past, now it has a duty of historical reparation.”

Advertisement

In 1993 Chile enacted its Indigenous law, recognizing eight peoples, including the Mapuche – who make up 12% of Chile’s population – and the Rapa Nui of Easter Island. In some cases land titles and limited legislative representation have been offered, but the continued expansion of timber, mining and agricultural projects – combined with heavy-handed policing – has led to rising social tensions in the south of the country.

Subsequent European exploration left a legacy of bleak place names – Port Famine, Useless Bay, Tortuous Passage – but the newcomers had limited contact with Indigenous people.

In November 1886 Ramón Lista, an Argentinian explorer landed on the windswept and barren shores of the Bay of San Sebastián in Tierra del Fuego. By his own account, lacking the resources to take them prisoner, he ordered his accompanying soldiers to shoot 28 Selk’nam, including women and children, that they encountered there.

In the following 40 years Argentinian and Chilean ranchers and miners would exterminate thousands of Selk’nam, dispatch others to German human zoos, and send many more to Salesian Christian missions where they frequently succumbed to disease. The last known full-blood Selk’nam died in 1974.

Indigenous Chileans defend their land against loggers with radical tactics

On the Argentinian side of Tierra del Fuego, the Selk’nam of the maternal line have been recognized by law since 1994 and 36,000 hectares provided to the community as ancestral lands. Last year 25 November - the anniversary of the massacre perpetrated by Lista - was recognized as the Day of the Selk’nam Genocide and flags were flown at half-mast.

“The Argentinian state came to exterminate, it was a genocide and now it is a day of mourning” says Vanina Ojeda, a Selk’nam who is now secretary of Original Peoples for Tierra del Fuego. “For years the state tried to make invisible the crimes of the past, now it has a duty of historical reparation.”

Advertisement

In 1993 Chile enacted its Indigenous law, recognizing eight peoples, including the Mapuche – who make up 12% of Chile’s population – and the Rapa Nui of Easter Island. In some cases land titles and limited legislative representation have been offered, but the continued expansion of timber, mining and agricultural projects – combined with heavy-handed policing – has led to rising social tensions in the south of the country.

A woman looks at a painting representing members of the Selk’nam people in Santiago, Chile, in February.

Photograph: Alberto Valdés/EPA

Mapuche flags were a prominent symbol of Chile’s 2019 protest movements that coalesced around the goal of changing the constitution.

In Chile’s 2017 census 1,144 respondents self-identified as Selk’nam but they were dispersed across the country. In 2018 Vásquez attended a cultural event for Selk’nam that he had seen posted on Facebook. “We hugged and we cried because it was the first time we had met people from our community, our brothers and sisters,” he says.

With the help of the community he was able to gather further details of the life of his grandfather, Carmelo Chogue, who had spent his childhood in the Salesian mission on Isla Dawson, a remote island so inhospitable it was later used to intern political prisoners during the Pinochet dictatorship.

In October 2020 Vásquez was able to visit Tierra del Fuego for the first time. When he crossed the Strait of Magellan, emotion overcame him.

“I saw the land where my father had come from, I saw Isla Dawson and when I got off the boat the first thing I did was to take a handful of earth and grasp it tightly with my hand. Then I started to cry and cry.”

No comments:

Post a Comment