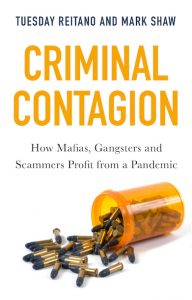

In Criminal Contagion: How Mafias, Gangsters and Scammers Profit from a Pandemic, Tuesday Reitano and Mark Shaw explore how organised crime has adapted and flourished during the COVID-19 pandemic by exploiting human vulnerability. Parisa Kabir recommends this expertly written book to readers who want to learn more about the impacts of COVID-19 on organised crime and how dimensions of global health intersect with the criminal world and illicit activity.

Criminal Contagion: How Mafias, Gangsters and Scammers Profit from a Pandemic. Tuesday Reitano and Mark Shaw. Hurst Publishers. 2021.

Without a doubt, the COVID-19 pandemic has drastically changed the way our world functions and reconfigured the way societies interact and behave worldwide. In their recent book, Criminal Contagion, Tuesday Reitano and Mark Shaw elucidate the ways in which organised crime has adapted, and consequently flourished, during the pandemic by exploiting human vulnerability. Reitano and Shaw investigate various aspects of the ‘criminal underworld’ and its illicit activities and pathways for illegal commodities, including controlled substances and humans.

Both authors are directors at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC) with extensive experience working at the United Nations. Reitano has published widely on organised crime and the security-development nexus within a global context, while Shaw is a prolific author of work in the areas of policing, organised crime and crime in general, with a particular interest in sub-Saharan Africa. Their in-depth knowledge of and expertise in criminal networks, corruption and the political economy of crime are demonstrated throughout Criminal Contagion. Set within the very recent context of COVID-19, the book combines a variety of sources, including news articles, reports, GI-TOC data and scholarly literature, along with primary research, including key informant interviews.

The book is clear, well-structured and engaging in describing and exploring the evolution and primary features of global crime prior to the pandemic. It examines various aspects of organised crime and illicit markets associated with the chaos and dynamics of COVID-19 and related state policy responses.

Image Credit: Photo by Dan Dennis on Unsplash

Reitano and Shaw first introduce the contemporary political economic context of organised crime and how criminal enterprises have exploited vulnerabilities for self-gain, with costly consequences. Each chapter of Criminal Contagion focuses on a specific crime or criminal enterprise as a case study and then proceeds to provide a historical overview supported by various data within transnational contexts. Topics include, but are not limited to, the illicit wildlife trade and increases in poaching, human trafficking and smuggling as well as cybercrimes constituting ‘virtual violence’, involving medical disinformation, hacking, ID theft, banking fraud, and romance and 419 scams.

Reitano and Shaw also devote an entire chapter to ‘criminal coronomics’, discussing illicit financial flows and the politics of tax havens, poverty and criminal recruitment, money laundering in bankrupt economies, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as well as oil and debt in Africa. Criminal Contagion ends with recommendations on how to best move forward, largely in the context of strengthening surveillance amidst the weakening of state legitimacy.

Both fascinating and concerning is how Reitano and Shaw highlight the ability of crime to adapt to its cultural and social environments, and how it spreads into all sectors of society, like an infection itself. The book illustrates the resilience of the ‘criminal underworld’ and its ability to innovate, such as through cybercriminal activity and by exploiting governance vacuums. One example describes how phishing scams sent emails claiming to provide government-funded stimulus payments or COVID-19 test results as a means to gather personal information and introduce malware, or malicious software (121). One section of the book explains how people dealing drugs reportedly disguised themselves as health-care or fast-food delivery workers to escape detection while out in public and on the streets (20).

Although Criminal Contagion provides an extremely robust and comprehensive understanding of illegal activities in the context of COVID-19, one area that could have been explored in more depth is how governments and institutions play a role in the flourishing of organised crime. However, Reitano and Shaw do emphasise the need to build stronger institutions and redirect resources to properly regulate and address the enduring nature of organised crime.

Criminal Contagion is highly recommended for readers who want to learn more about the impacts of COVID-19 on organised crime and how dimensions of global health intersect with the criminal world and illicit activity. Readers also seeking to expand their knowledge on current and future trends associated with criminal activity will find this book very helpful in understanding where to better allocate resources and what policies may best address organised criminal activity at this scale. Although the structure and language of Criminal Contagion are not difficult to follow, upper-year undergraduate students, postgraduate students and those working in relevant fields, including governance, law and public health, are likely to have enhanced understanding and appreciation of the book.

As a student in the University of British Columbia’s Global Resource Systems programme, this book provides insights into understanding the contemporary global dynamics of health and crime in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic when criminal justice systems have been at their weakest. This timely book will serve as a great teaching resource for professors assigning readings for courses focusing on the intersections of COVID-19, crime, health, governance, commerce and/or law. With Criminal Contagion, Reitano and Shaw have expertly written a book for scholars, practitioners, students and policy experts alike.

- This review first appeared at LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3RyTuiF

About the reviewer

Parisa Kabir – University of British Columbia

Parisa Kabir (she/her) is a fourth year undergraduate student at the University of British Columbia in the Global Resource Systems program. She is currently a co-op student working with the Centre for Gender and Sexual Health Equity. She hopes to specialise in the field of global and public health. Parisa has done an extensive amount of volunteer work within her community, including with the Canadian Red Cross and the Aga Khan Foundation as well as various clubs and organizations at UBC. She has also had experience conducting research, having completed an undergraduate research project on food insecurity and having worked as a research assistant.

Without a doubt, the COVID-19 pandemic has drastically changed the way our world functions and reconfigured the way societies interact and behave worldwide. In their recent book,

Without a doubt, the COVID-19 pandemic has drastically changed the way our world functions and reconfigured the way societies interact and behave worldwide. In their recent book,

No comments:

Post a Comment