By Michael Irving

August 02, 2022

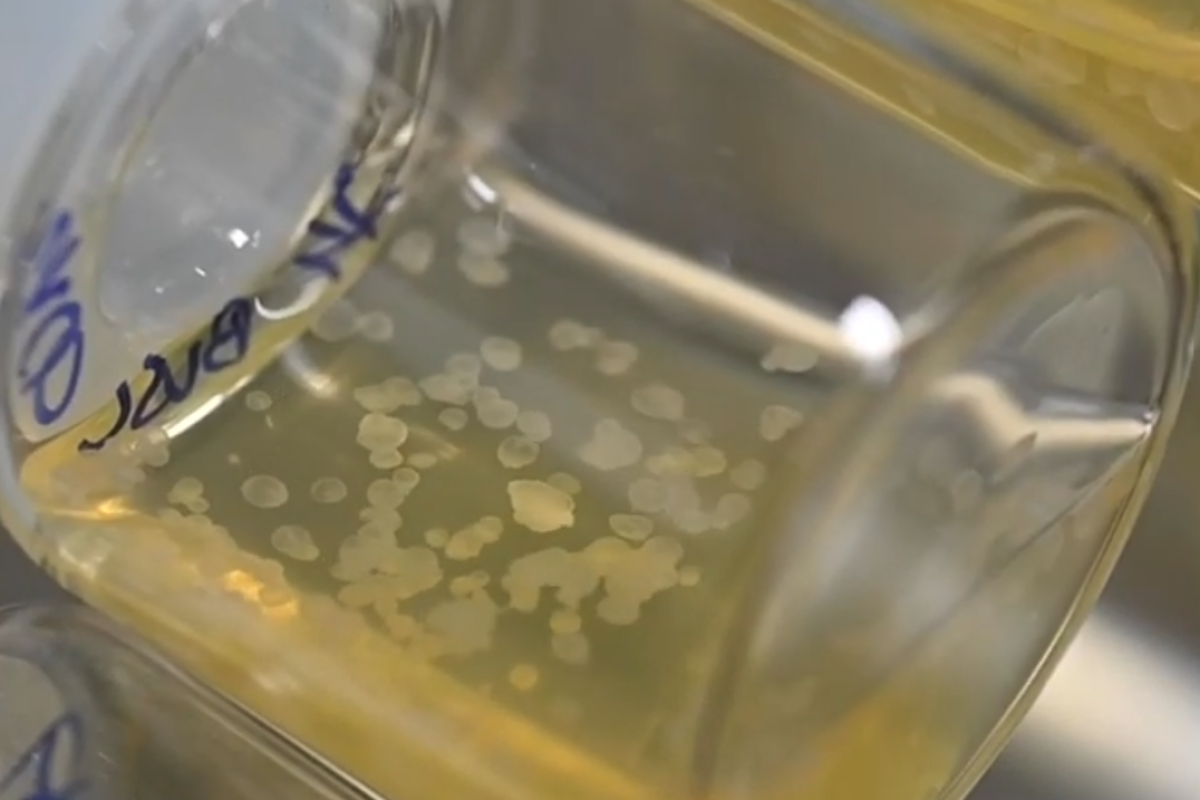

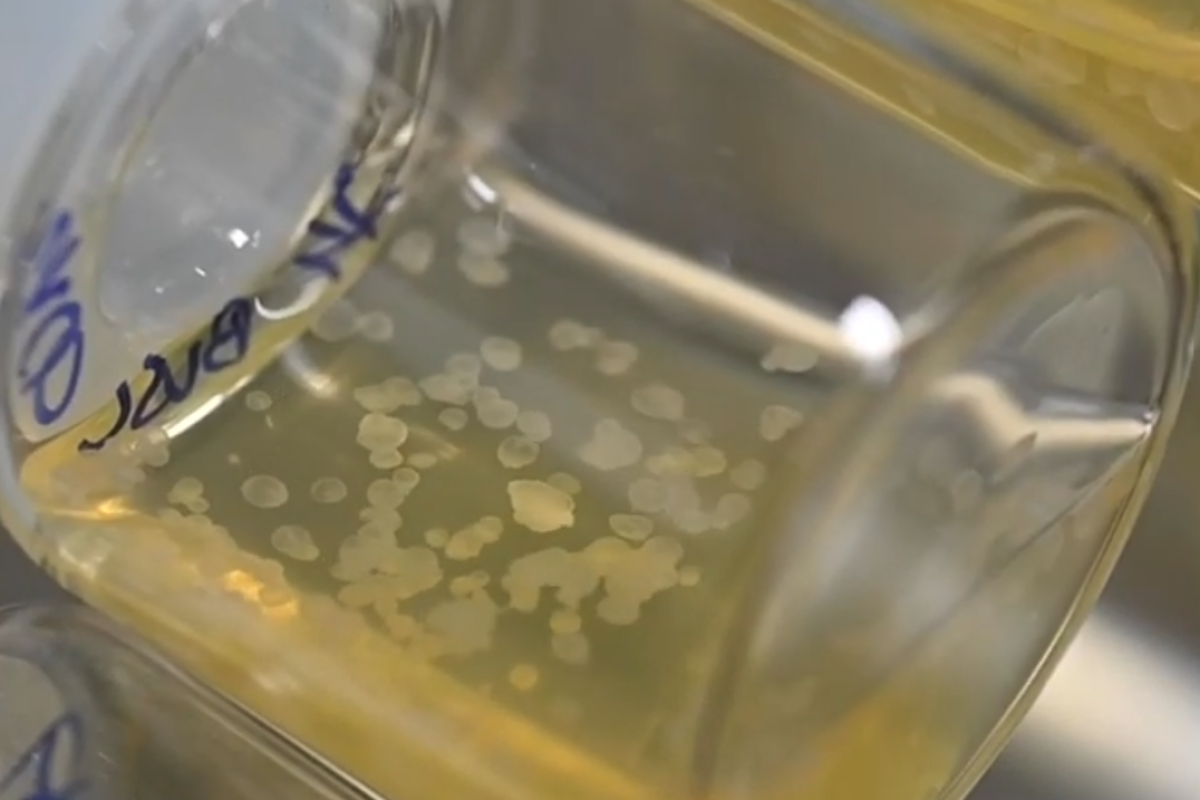

A sample of the synthetic embryos in the nutrient solution

Weizmann Institute of Science

Researchers have created synthetic mouse embryos out of stem cells, removing the need for sperm, eggs and even a womb. They were then grown to almost half the entire gestation period, at which point they had all of the organ progenitors, including a beating heart. The tech could eventually be used to grow organs for transplant.

The new study, from researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, built on two branches of the team’s previous research. The first involved reprogramming stem cells into a “naive” state that allows them to differentiate into all other cells, including other stem cells. The other work focused on developing a device that could grow embryos more effectively outside of the womb.

August 02, 2022

A sample of the synthetic embryos in the nutrient solution

Weizmann Institute of Science

Researchers have created synthetic mouse embryos out of stem cells, removing the need for sperm, eggs and even a womb. They were then grown to almost half the entire gestation period, at which point they had all of the organ progenitors, including a beating heart. The tech could eventually be used to grow organs for transplant.

The new study, from researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, built on two branches of the team’s previous research. The first involved reprogramming stem cells into a “naive” state that allows them to differentiate into all other cells, including other stem cells. The other work focused on developing a device that could grow embryos more effectively outside of the womb.

A sample of the synthetic embryos in the nutrient solution

Weizmann Institute of Science

By combining the two techniques, the team has now grown some of the most advanced synthetic mouse embryos to date. They started with naive mouse stem cells, which had been cultured in a Petri dish for several years prior. These were separated into three groups that would play key roles in the embryo development.

One group contained cells that would develop into embryonic organs. The other two were treated with master regulator genes of extra-embryonic tissues – the placenta for one group and the yolk sac for the other. The three types of cells were then mixed together in the artificial womb, which carefully controls pressure and oxygen exchange, and gently moves the beakers around to simulate natural nutrient flow.

Once inside, the three types of cells clumped together to form aggregates, which had the potential to develop into embryo-like structures. As might be expected, the vast majority failed at that stage, with only 0.5% – or 50 out of about 10,000 – successfully developing further.

A synthetic embryo over its eight days of development

Weizmann Institute of Science

Those lucky few started to form spheres of cells, and eventually elongated structures resembling natural embryos, complete with placentas and yolk sacs. Thy were allowed to develop for over eight days, which is almost half of the mouse gestation period, by which point they had formed all the early progenitors of organs. That includes a beating heart, blood stem cell circulation, a well-shaped brain, an intestinal tract and the beginnings of a spinal column.

On closer inspection, the team found that the shape of internal structures and the gene expression patterns of these synthetic embryos matched natural ones to within 95%.

INCUBATOR

Weizmann Institute of Science

Their organs also seemed to be functional.

The team says that this technique could help reduce the need for live animal testing, and could eventually become a plentiful source of tissues and organs for transplantation.

“The embryo is the best organ-making machine and the best 3D bioprinter – we tried to emulate what it does,” said Professor Jacob Hanna, lead researcher on the study. “Instead of developing a different protocol for growing each cell type – for example, those of the kidney or liver – we may one day be able to create a synthetic embryo-like model and then isolate the cells we need. We won’t need to dictate to the emerging organs how they must develop. The embryo itself does this best.”

The research was published in the journal Cell.

Source: Weizmann Institute of Science

The team says that this technique could help reduce the need for live animal testing, and could eventually become a plentiful source of tissues and organs for transplantation.

“The embryo is the best organ-making machine and the best 3D bioprinter – we tried to emulate what it does,” said Professor Jacob Hanna, lead researcher on the study. “Instead of developing a different protocol for growing each cell type – for example, those of the kidney or liver – we may one day be able to create a synthetic embryo-like model and then isolate the cells we need. We won’t need to dictate to the emerging organs how they must develop. The embryo itself does this best.”

The research was published in the journal Cell.

Source: Weizmann Institute of Science

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment