The Promethean Antikythera Computer of Greek Civilization

Painting of the Antikythera Mechanism by the Greek mathematician Dionysios Kriaris. One sees the Cosmos, the front of the computer, and the back with the black spirals of the 19-year Metonic calendar and the 18-year predictive Saros dial. Courtesy Kriaris

Overview

Suppose you could travel back in time to the third century BCE, and visit Alexandria, the capital city of the Greek kingdom of Egypt. Arguably it was the most enlightened, wealthy, and powerful of all the Greek states that flourished after the death of Alexander the Great.

Alexandria was famous for: its Mouseion, university- institute of advanced studies, and the Great Library which was the repository of all the collected wisdom and knowledge of the Greek and Mediterranean world. The Great Library was rather as if you had merged Cambridge, with Harvard, MIT, and the Library of Congress. Among its collections one could find the works of epic poets like Homer and Hesiod, tragic poets like Aeschylos, Sophocles, and Euripides, historians like Herodotos and Thucydides, as well as philosophers like Thales, Anaximander, Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle, and scientists like Demokritos, Hippokrates, Alkmaion of Croton, Aristarchos of Samos, Eratosthenes, Euclid, Archimedes, Hipparchos, Geminos, Ptolemaios and Galen.

However, if you were to travel forward in time to visit Alexandria 800 years later, in the fifth century of our era, you would find no trace of the Great Library of Alexandria, nor of its sister Mouseion-university. Both had been destroyed by Christian religious zealots. In 415 of our era, a mob of Christian monks told the world that Christianity had no need of the Greeks, nor of their philosophy, science, or literature. To drive home their point, they publicly murdered and tore limb from limb Hypatia, the mathematician and philosopher who headed a leading school of philosophy in Alexandria.

In the 6th century, Justinian, the Christian Emperor of the Eastern Roman empire (Medieval Greece), closed and suppressed the Platonic Academy in Athens, which had existed for more than 900 years. These attacks upon the culture of ancient Greece heralded an enveloping wave of darkness and ignorance for both East and West. This anti-intellectual, Christian fanaticism plunged Europe into the Dark Ages, for almost a thousand years.

These officially sanctioned attacks on Greek philosophy and science gave Christian monks a license to destroy and obliterate treasures of science, including some of the works of Archimedes, the mathematical and engineering genius of the 3rd century BCE. The monks literally scraped the ink from the parchment pages of Archimedes’ scientific texts and then re-filled the erased pages with the texts of religious hymns.

It happened.

Modern dramas with ancient Greek science

In 1998, an American paid $ 2 million for a 769-year-old Christian prayer book known as a palimpsest (a manuscript from which the original text had been scraped-off and which had then been used again). Christian prayer-texts were superimposed over the erased scripts of three works of Archimedes. The slim hope of revealing the lost thoughts of Archimedes was the sole reason why the philanthropist was willing to pay a vast sum of money for the ‘ghost’ of a vanished book.

In 2005, seven years after the Archimedes palimpsest surfaced in New York, an even greater drama was unfolding in the basement of the National Museum of Archaeology in Athens. A team of Greek, British and American scientists and engineers had been struggling to “decode” the secrets of an ancient Greek astronomical device: the “Antikythera Mechanism.” This ancient astronomical computer had been raised from the waters of the tiny Aegean island of Antikythera by sponge divers in 1900. However, in 1900, the technology which could probe the innermost workings of this eroded and encrusted lump of metal did not exist.

Meanwhile, Greek, and foreign scientists kept photographing and handling the fragile surviving fragments of the ancient device. This precipitated the break-up of the mechanism to some 82 fragments.

Front and back sides of the 7 largest and most important fragments of the Antikythera computer. Fragment A is the governing part of the device, enclosing 27 of the surviving 30 gears. Some of those gears are visible on the back side of Fragment A. The back side of Fragment B shows the spirals of the 235-month 19-year Metonic calendar. Courtesy Tom Malzbender and Hewlett Packard.

The early twentieth-century investigators of the Antikythera device also played a guessing game, calling it different names and proposing wrong explanations of its origins and functions. In general, they were reluctant to admit it was part of Hellenic culture. Derek de Solla Price, a British physicist and historian of science and professor at Yale, rejected those doubts and documented in his 1974 seminal report, Gears from the Greeks, that the Antikythera computer was “a singular artifact, the oldest existing relic of scientific technology.” It took another 30 years or so of technological advances before science was able to confirm and advance Price’s findings.

Using microfocus X-ray computed tomography (X-ray CT) and polynomial texture mapping (PTM), belonging to British and American companies, scientists were shocked to discover an interior mechanism of meshed toothed gears, which pointed to a sophisticated and complex mathematical instrument. From the nearly invisible inscriptions engraved on the front and back plates of the bronze device, the experts estimated that the computer was probably manufactured in the 2nd century BCE. In other words, it was over 2,200 years old.

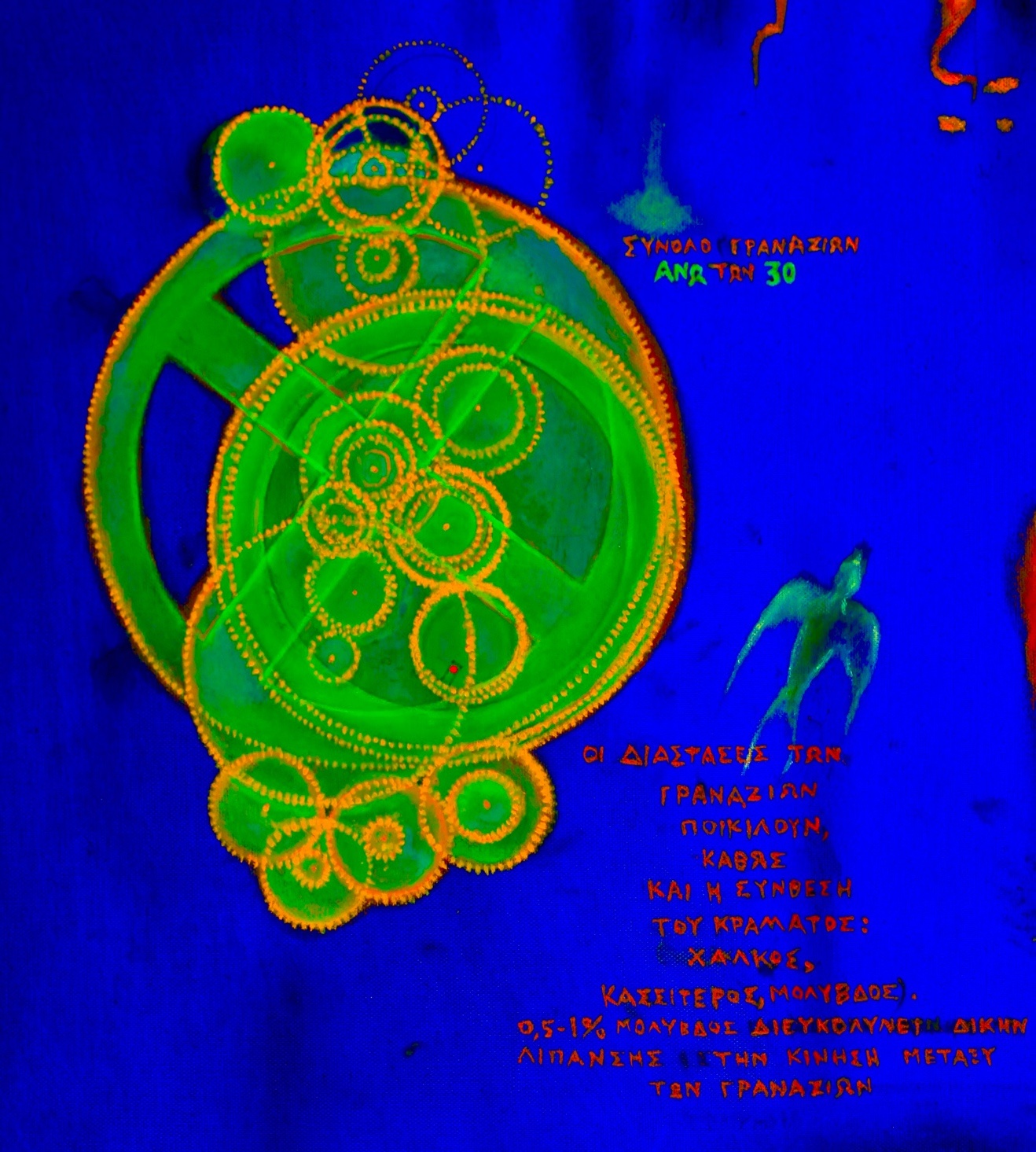

The gears in the interior of the bronze Antikythera astronomical computer. Most of these surviving gears are inside Fragment A. Painting by the Greek artist Evi Sarantea. Courtesy Sarantea.

How can the sale of a Medieval Christian prayer book, (a palimpsest written over the works of Archimedes), possibly be linked to the x-ray investigation of the Antikythera device? In fact, they are parallel threads of the same narrative, which illuminate the fate of Greek science and civilization.

What happened to the advanced work of scientists like Archimedes during the Dark Ages?

Did the ancient Greeks really develop a sophisticated science and technology more than 2,000 years ago? Moreover, if they did achieve such levels of complexity, is the Antikythera Mechanism the product of those same advanced technologies?

Greek computer of genius

My research for writing my book on the Antikythera Mechanism, reveals that the ancient Greeks did indeed develop an advanced science and advanced metal fabrication technologies, which enabled them to build the Antikythera machine. This is extremely important because, to date some classical scholars and scientists have labored under the illusion that modern science is largely the product of post 15th century European thought. They forget that without the mathematical physics of Archimedes Galileo might have been a priest of barber but not a famous physicist. Moreover, they believe that the Greeks never developed technology, much less the advanced technologies needed to construct a mechanical computer and universe, such as the Antikythera Mechanism. In fact, some of the enemies of Hellenic civilization say the Antikythera Mechanism is a time machine, the handiwork of extraterrestrial astronauts.

This propaganda against the Greeks fits nicely with the hubris of scientists dismissing Greek achievements. They say, modern science has taken us to the moon. How can the ancient Greeks possibly be compared to us, they ask. The Greeks fought their wars with bows and arrows, did they not? We have ICBMs, satellite guided predator drones and nuclear weapons. Why should we care if the Greeks ever developed advanced technology?

Why the Greeks?

“We are all Greeks.” These were the heartfelt words of the English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in 1821: “Our laws, our literature, our religion, our arts, have their roots in Greece.”[1] Shelley was one of many Philhellenes who fought alongside the Greeks during the War of Independence, in the heroic struggle to expel the Turkish occupiers of their homeland.

Jacob Burckhardt, the famous Swiss cultural historian, was grateful to the Greeks for laying the foundations of Western culture, enabling men to become civilized. He said in 1872 that the Europeans see the world through the eyes of the Greeks and to abandon them would be to accept their own decline.[2]

In 1948, the English poet W. H. Auden suggested that the people of the West owe their very existence to the Greeks. He said the Greeks taught us to think about thinking, that is, to ask questions. Without the Greeks, he said, “we would never have become fully conscious, which is to say that we would never have become, for better or worse, fully human.”[3]

In the late 1950s, E. J. Dijksterhuis, Dutch historian of mathematics and natural sciences, said that any inquiry on the origins of present-day knowledge inevitably leads us back to Hellas, especially in mathematics and natural sciences.[4]

And in 1999, the English scholar and historian, Charles Freeman, argued that the Greeks “provided the chromosomes of Western civilization.”[5]

These scholars are right. The Greeks are us. Greek science made the Antikythera astronomical computer. The Greeks thought of science and technology existed mainly for the good of society as well as for understanding nature.

Computer of heavens and Earth

The Antikythera Mechanism was not merely a bauble for the elite to educate themselves about the heavens. It was the workhorse of an evolving technology which provided knowledge about the heavens, connecting the Greeks to Nature, their culture. and the gods.

The Antikythera computer illuminates the relevance of Greek thought and engineering to our own times. Our computer-based society is undoubtedly built on the marvels of high technology. However, if technology is not used for the ‘public good’ it can undermine society rather than being a benefit to it, as we see in the current misplaced excitement about Artificial Intelligence.

Galen, the Greek medical genius of the 2nd century of our era and the greatest physician after Hippocrates, put it bluntly. If wealth is put before virtue, he said, it spoils and corrupts science.[6] In marked contrast, the Antikythera device came into being to serve the public good. It brought the heavens nearer to Earth and into human understanding. It served as an accurate calendar of human events and a calendar of the celestial universe, a moving map of the constellations and a mirror of nature and the heavens.

We admire the ancient Greeks for their invention of Democracy. We celebrate their unsurpassed achievements in providing us with the foundations of: literature, epic poetry, theater, architecture, mathematics, geometry, astronomy, and the Olympic Games.

Greek foundations of modern science

It is the fact that the Greeks, laid the foundations of modern science, the ultimate touchstone of knowledge and power, that makes them so important to us. That is why the discovery of a vandalized book of Archimedes was big news and the decoding of a 2200-year-old Greek computer has been of extraordinary importance.

The Antikythera discovery was undoubtedly the key to unlocking a better understanding of ancient Greek science. This ancient computer gives us profound new insights into the science and philosophy of ancient Greece that has reshaped our conception of the origins of Western science. Moreover, on a purely human level, the story of the discovery of the computer, the researchers and scholars who unraveled its secrets is a compelling drama in its own right. Why did Modern Greek scientists wait a century and the initiative of foreign scientists before they embarked on the decoding of this ancient computer? Could it be that the state of Greece could not afford the research? Indebted Greece has been looted by foreigners, so it could not even think of the importance of the Antikythera computer. But the few Greek scientists that grasped the significance of the ancient device value it much more than their British and American colleagues.

Laptop predictive computer

An additional view of the interlocking toothed gears of the Antikythera computer. Modified by Alexander Nicaise of the Skeptical Inquirer. Courtesy Nicaise.

The complicated set of interlocking cogs and wheels of the Antikythera Mechanism were governed by a differential gear. Ιn itself this was a technological marvel of enormous importance. It could accurately predict the phases of the Moon. Throughout the twentieth century and for almost two decades of the twenty-first century, archaeologists, scientists, and historians of science struggled to unlock the true nature of this ancient computer. Finally after the new discoveries of Derek de Solla Price in 1974 and again those discoveries of 2005, the picture is clear.

The Antikythera device played the role of a mechanical universe. In fact, it was a predictive mechanical universe in itself, carrying out the predictive legacy of the Titan god Prometheus (forethought). It predicted eclipses of the Sun and the Moon. It computed the motions and positions of the planets. It provided an accurate calendar for farmers, who were concerned over when to sow and harvests. It enabled priests to make sacrifices to the gods at the correct season, that is, when the gods expected the offerings.

The Antikythera computer also tracked the Panhellenic religious and athletic festivals like the Olympics. It was powered by a simple manual crank. Yet, for all its simplicity, this portable (laptop) astronomical device was a product of an advanced science and technology. Its triumph was to unite the heavens and the Earth, to illuminate the workings of the Cosmos for human inspection and to provide practical knowledge that enriched the lives of its users.

An early reproduction of the Antikythera Mechanism by Dionysios Kriaris. The front or Cosmos does not include the planets, but it shows a golden sphere of the Sun at the center and a smaller sphere depicting a phase of the Moon. This Cosmos is surrounded by two spherical zones, the outside representing the 365-day year calendar. The inside circle is the Zodiac of 12 constellations. Behind the Cosmos, we see the upper spiral of the 19-year Metonic calendar. The lower spiral is the 18-year predictive Saros dial. Courtesy Kriaris.

This sophisticated predictive machine embodied the scientific method and philosophy of Aristotle (fourth century BCE), the mathematics of Archimedes (third century BCE), the engineering of Ktesibios and Archimedes (third century BCE), and the mathematical astronomy of Hipparchos (second century BCE). It was Hellenic civilization in miniature.

Notes

1. The Complete Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley (New York: The Modern Library, 1994) 501. ↑

2. Jacob Burckhardt, The Greeks and Greek Civilization, tr. Sheila Stern, ed. Oswyn Murray (New York: St. Martin Press, 1998) 12. ↑

3. W.H. Auden, Forewords and Afterwords, ed. Edward Mendelson (New York: Random House, 1973) 32. ↑

4. E. J. Dijksterhuis, “The Origins of Classical Mechanics from Aristotle to Newton” in Critical Problems in the History of Science, ed. Marshall Clagett (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969) 164. ↑

5. Charles Freeman, The Greek Achievement (New York: Penguin Books, 2000) 434. ↑

6. Galen, The Best Doctor is also a Philosopher 57-61, in Selected Works, tr. P. N. Singer (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997). ↑

No comments:

Post a Comment