IT'S A PROFESSION MAKE IT FULL TIME

HIRE WOMEN

2023/10/01

Assistant Chief Alex Justi puts away a hose after testing engine pumps and hoses in the Dalzell Grade School parking lot on Aug. 31, 2023. - Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune/TNS

Assistant Chief Alex Justi puts away a hose after testing engine pumps and hoses in the Dalzell Grade School parking lot on Aug. 31, 2023. - Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune/TNS

DALZELL, Ill. — The 76-year-old man was sitting at his kitchen table one Tuesday morning in June when he lost consciousness and fell to the floor.

A few blocks away, Alex Justi’s emergency pager went off. The 24-year-old firefighter and paramedic is one of only six people who make up Dalzell’s volunteer-run fire department, and one of only two who lives in the town of about 660 residents in north-central Illinois, near Starved Rock State Park.

Justi raced to the station, jumped in an engine and drove, solo, to the man’s house. Once there, he quickly realized the man wasn’t breathing. Justi placed a device over the man’s nose and mouth and manually pumped oxygen into his lungs, continuing for at least five minutes until first responders from a neighboring town arrived to help.

The man survived. But, Justi reluctantly acknowledged, the outcome could have been different.

“If somebody wasn’t breathing for him, he would have been dead by the time the ambulance showed up,” Justi said.

“That was when we realized that we need some help here.”

Just over half of all firefighters in the United States are estimated to be volunteers: men and women who, like Justi, leave their homes and jobs at any moment to respond to house fires and car crashes, medical emergencies and natural disasters.

In Illinois, about two-thirds of the state’s roughly 1,100 fire departments rely almost entirely on volunteers.

And, with few exceptions, those departments are running out of volunteers.

The fluctuating ranks of volunteer departments make it difficult to accurately track the losses. But fire chiefs across Illinois say they’re facing historic staffing lows.

In Dalzell, the roster of six should be 16 to be fully staffed, said Chief Tom Riordan. Over in Divernon, in central Illinois, Chief Randy Rhodes said he’s lost eight volunteers just in the past two years. And the bylaws for the Galena Fire Department, billed as the state’s oldest, cap volunteer membership at 62. They’ve got 24, Chief Bob Conley said.

The alarming shortages come amid increased service demands driven by rising medical calls attributed largely to the state’s growing senior population.

As a result, departments are increasingly relying on surrounding agencies to aid in their emergency responses, while some chiefs have tapped into federal grant dollars to pay for part-time help to augment their aging rosters of existing volunteers.

“It’s going to become very critical, very shortly,” said Kevin Schott, an Illinois Firefighters Association board member. “The county and the state are going to need to look at this because the public safety is going to be impacted.”

Firefighting organizations and some state lawmakers have tried over the years to address the dearth of volunteers, offering tax breaks and other incentives aimed at buoying department ranks.

Those efforts have thus far found little success. And some department leaders fear the worst is yet to come.

If nothing changes, fire chiefs in Dalzell and elsewhere say they’ll no longer have enough people to answer medical calls, ceding that responsibility to neighboring agencies or private ambulance services. Other departments are looking at mergers as a way to hopefully prolong their survival.

All this could put hundreds of thousands of Illinois residents in the dangerous position of having to wait longer for help to arrive.

“A lot of people think when they call 911, help is going to be there,” said Jim Gielow, chief of the volunteer fire department in Pinckneyville, in southern Illinois. “They may not realize one day that won’t be the case.”

A long tradition, a slow decline

It wasn’t always like this.

Veteran fire chiefs wax nostalgic about decades past when the volunteer fire service thrived, ensconced in a centuries-old tradition (Ben Franklin is credited with creating the model with his Union Fire Company in Philadelphia) and encapsulated in a 1931 “The Saturday Evening Post” cover illustration by famed artist and chronicler of Americana, Norman Rockwell.

They had full rosters and waiting lists back then. They had generations of the same last names in their ranks, and high school “explorer” programs, like internships, that infused their departments with a youthful energy.

The residents of those communities, meanwhile, enjoyed fire protection without the costs of salaries and benefits, which freed up tax dollars for police and parks and roads.

The system worked, until it didn’t.

To be clear, the long, steady decline of the volunteer fire service isn’t unique to Illinois. Headlines across the country tell similar stories of depleted ranks

In 1995, there were an estimated 838,000 volunteer firefighters in America, according to figures from the National Fire Protection Association.

Twenty-five years later, that number fell to 676,900.

The ratio of volunteers per 1,000 people dropped by nearly 25% in that same time, estimates show.

There are plenty of explanations for the downfall.

One obvious factor is Illinois’ shrinking population. The state lost a little over 104,000 residents between 2021 and 2022, U.S. Census Bureau estimates show. The losses were felt in all but 11 of the 102 counties.

Some chiefs believe the sense of community pride and civic duty that once motivated people to volunteer has vanished.

“It just seems to be getting harder and harder to get the younger generation to step up and donate their time,” said Eric Lancaster, fire chief in the central Illinois town of Girard, population 1,785. “It’s definitely been a struggle. And it is definitely getting worse.”

And while it’s true that volunteerism has generally fallen over the last decades, a report earlier this year from the U.S. Census and AmeriCorps found that Illinois was one of only two states (Wyoming the other) that did not see a drop in the percentage of Americans who formally volunteered with organizations between 2017 and 2021 (Illinois’ formal volunteering percentage went from 28.1% to 28.3% in that time).

Changing economic conditions also play a role. Families are increasingly unable to survive on one income. And with fewer job opportunities in rural communities most dependent on volunteer firefighters, people are forced to travel farther to work for employers who aren’t always as willing to let their staff answer emergency calls.

Then there’s the simple reality that being a volunteer firefighter is demanding on the person and their families. Emergency pagers can go off during family dinners and at 2 a.m., on Christmas morning and at a school recital.

“There were times I missed things,” said Lt. Chris Garza, 48, a father of two who has volunteered with the Galena department for the past 13 years. “And you can’t get those moments back. But I know I’m helping somebody when they’re having the worst day possible.”

Others say the training requirements have made the volunteer fire service a hard sell. A basic firefighter certification can take around 180 hours to obtain, and though volunteer firefighters aren’t required to be certified, they do have to be trained to the state standard.

That means departments typically ask their members to attend weekly training sessions, usually one night a week.

Emergency medical training, also not required, can take another six months, and is often crucial given that medical calls account for about 70% of the incidents Illinois fire departments respond to each year.

“Guys get burned out after a while,” said Pinckneyville’s chief, Gielow. “They’re a little more on edge, working their full-time jobs and running a bunch of calls. It’s hard on their personal lives. It all kind of adds up.”

‘We can’t let off the accelerator’

On the last Monday of July, about 30 members of the Glen Ellyn Volunteer Fire Company gathered for a weekly training exercise. In this particular session, they wore full protective gear, face masks and oxygen tanks strapped to their backs, and waited for their turns to go inside an abandoned motel to rescue one of their own from a room filled with smoke billowing from a machine.

There was Vinh Lu, 50, a freelance film location scout and father who started volunteering with the fire department nearly five years ago because, like his military service, it gave him the chance to be part of something bigger.

Richard Arehart, 49, wanted to be a firefighter as a kid but instead became a banker. Nearly three years ago, he saw an online ad looking for volunteers and moved his family to Glen Ellyn so he could make his childhood dream come true.

Clare Doran, 53, went to a department open house seven years ago thinking she’d file paperwork or tidy up the office, only to realize the ask was to be a firefighter.

“I was like, I don’t think that’s a good idea. I don’t think I could carry anybody out,” Doran remembered. “And chief said, we’ll teach you. And they taught me.”

The west suburban fire department is one of the few in the Chicago area that still relies almost entirely on volunteers. And with about 60 members, it’s thus far managed to avoid the shortages that have plagued other volunteer departments. About 35 people showed up to a recruitment open house earlier this month, said Matt Andris, second assistant chief. Seven submitted applications to join, with more expected.

“I can’t put a finger on why we’re successful other than really hard work,” Andris said.

There are, of course, other contributing factors.

For one, the village has a separate, paid ambulance service. That means fire department volunteers aren’t required to go through more intensive emergency medical training, nor are they faced with the added strain of answering medical calls, which state data show have climbed by 35% in the last decade.

Unlike in rural parts of the state, Glen Ellyn’s 28,000 residents offer a large pool of potential volunteers, plenty of whom work in professions with flexible schedules that allow them more opportunity to donate their time. Some department members volunteer elsewhere. Doran, for example, volunteers with four other community groups.

The department also hired a Glen Ellyn-based marketing company to lead its recruitment efforts, which include targeted mailers, Google ad campaigns and volunteer profiles posted on the department’s website.

“We can’t let off the accelerator,” Chief Chris Clark said. “We have to continue to recruit the way we do. That’s just a fact for any volunteer organization.”

‘The bigger conversation is coming at us’

For the volunteer fire service to survive, recruitment needs to be the focus of every person in the department, said Steve Hirsch, a volunteer firefighter in Kansas and chair of the National Volunteer Fire Council.

“That’s our success,” he said. “It’s all those who wear red helmets out there recruiting friends and bringing names to us all the time.”

Departments also need to make sure their recruitment efforts are geared toward women and people of color, two groups that have historically been underrepresented in the fire service.

“We’ve not done a good job of recruiting in those communities,” Hirsch said of the fire service. “You’re overlooking half your population.”

It also takes money. The federal Staffing for Adequate Fire and Emergency Response grant program offers departments money for recruitment, retention and hiring. Since 2015, a little over 70 fire departments in Illinois received SAFER grants totaling close to $55 million.

Some departments use those federal dollars to pay volunteers a small stipend based on the number of calls they answered. Others have spent the money on part-time firefighters to answer calls during weekday hours when volunteer availability is especially limited.

Even Glen Ellyn, with its 60-member roster, still needs to augment its volunteer force by paying contractors to staff a fire engine during those hours.

But for some, the money’s not enough. They exist on fundraisers — 50/50 raffles, cookouts and craft fairs. They drive used fire engines donated by more fortunate peers and wear protective gear they can’t afford to replace despite it being too old by state standards.

Near the Quad Cities, the Colona Fire Department had hoped a federal grant could help it hire two people to cover daytime shifts in the town of 5,300 residents. Even with the money, the department couldn’t do it, Chief John Swan said.

“We’d have to pick up the tab after three years, and we can’t afford to do it,” said Swan, who noted that the department tried and failed last year to persuade residents to pass a tax increase to pay for daytime help.

“I have people in the department who are in their 50s and 60s that have to stay on because there’s no one available in the daytime,” he continued. “The public doesn’t understand. It just does not seem to sink in.”

Elected leaders in Springfield have passed bills in recent years aimed at giving volunteer departments a lift. One bill allowed volunteers to buy discounted tires for their personal vehicles at a government-discounted rate; another protects volunteers from being fired if they’re late to work or absent because of an emergency call.

This session, they passed a $500 tax credit for volunteer firefighters and a bill that allows state employees to leave work to attend firefighter training.

“Some of these bills look gimmicky,” said state Sen. Patrick Joyce, D-Essex, who sponsored the training bill. “But you have to throw something out there as a benefit. The bigger conversation is coming at us, and it’s going to be a lot of money.”

Lawmakers could pull from ideas generated 20 years ago, when Illinois fire department leaders and a bipartisan group of House members released separate reports on how to preserve the future of the state’s fire service.

Among the recommendations: Pass “pensionlike” legislation. Establish a life insurance and disability plan for volunteers. Create a scholarship program for volunteers and their families to attend Illinois universities and community colleges. Develop an incentive program for employers when their employees need to leave to answer emergency calls.

“I think you’re going to have a handful of firefighter bills every session from here to the end of time,” Joyce said. “You chip away at it and you try to address it.”

‘A dying tradition’

Their efforts might not be enough to save what Justi, the assistant chief in Dalzell, called “a dying tradition.”

In Peoria Heights, trustees in the town of 5,900 have been embroiled in an ongoing debate over the future of their volunteer fire department, which, like many, is short on volunteers.

After significant public pushback, trustees recently backtracked on a plan to offset that shortage by contracting help from the neighboring Peoria Fire Department, staffed by career firefighters.

What they do next will depend on whomever is picked as the next fire chief, said Matt Wigginton.

“There’s a lot of identity wrapped up in a local fire department,” Wigginton said. “But overarching, the biggest concern is public safety. At what point does that identity and nostalgia run up against public safety?”

Illinois already has a model program, called the Mutual Aid Box Alarm System (MABAS for short), that instantly dispatches help from neighboring fire departments when needed. Some fire chiefs think that system will become increasingly necessary for every call, no matter the severity.

“As much as anybody hates to have to call out to assist, I see it happening more and more now,” said Lancaster, the fire chief in Girard.

Others see a future where volunteer departments merge with their neighbors, hoping the combination of resources could free up enough money to pay people to offset dwindling volunteers.

But Swan, the chief in Colona, fears department consolidation will lead to longer response times.

Colona has a roster of 17 volunteers, Swan said, well below the 32 needed to be considered fully staffed.

“If nothing changes, there will be calls where we don’t show,” said Swan, who also serves as past president of the Illinois Firefighters Association.

It’s already happened, he said, medical calls at night that his department couldn’t answer because there was no one to respond.

“We have an ambulance backup, but minutes count,” he said.

If nothing changes in Divernon, Chief Rhodes said his department could no longer have the ability to respond to emergency medical calls. Those would then fall to neighboring towns and private ambulance services, both of which are also facing paramedic shortages.

A few high school seniors have expressed an interest in taking emergency medical classes and volunteering at the department. But that wouldn’t be until next summer, he said, and “we don’t know if we could hold it until then.”

Back in Dalzell, the forecast looks no better.

Two hospitals in the area closed this year — one in Peru, the other in Spring Valley — and the fallout has hit Dalzell and surrounding departments hard, exacerbating their staffing woes as ambulance crews are now tied up with longer transport times to and from hospitals.

Riordan, the fire chief, said they, too, might have to abandon medical calls.

“It’s the first thing that’s going to stop,” he said. “To be blunt, people are going to die because there’s nobody to take care of them.”

On a Thursday night in August, all six department members sat around a table in the fire station (also village hall) while Justi led a training on how to identify the types of hazardous materials that could be carried in the semitrailer trucks that lumber along Interstate 80 at the town’s northern border.

“Unfortunately, we’re not able to really mitigate the incident,” he told them. “Our job is to pretty much protect ourselves and everybody else that hasn’t been involved yet.”

All six said they were concerned about the department’s future and perplexed that no one in town seemed to care about the dire circumstances it faced.

“It’s really rough,” said Chris Mason, 44, a lieutenant who’s been with the department for nearly 17 years. “There’s not enough people to do anything.”

Later, they drove two fire engines and a water tanker truck — two of the three donated from other departments — to the elementary school parking lot to test hoses and engine pumps.

The first fire engine they tested, built in 1989, barely pumped water into its 500-gallon tank. It could be an easy fix, they hoped. If not, it could cost a few thousand dollars, money they can barely afford to spend.

During the testing, a man who lived nearby walked up to a few of the members. He’d been a volunteer years earlier but was asked to leave, he said, for missing too many training sessions.

He blamed his work schedule at the time. Now, standing in the grass as water sprayed from a fire hose attached to a nearby hydrant, he blamed the testing for turning the water at his house a funny color.

He asked them to stop, then turned and left.

2023/10/01

Assistant Chief Alex Justi puts away a hose after testing engine pumps and hoses in the Dalzell Grade School parking lot on Aug. 31, 2023. - Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune/TNS

Assistant Chief Alex Justi puts away a hose after testing engine pumps and hoses in the Dalzell Grade School parking lot on Aug. 31, 2023. - Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune/TNSDALZELL, Ill. — The 76-year-old man was sitting at his kitchen table one Tuesday morning in June when he lost consciousness and fell to the floor.

A few blocks away, Alex Justi’s emergency pager went off. The 24-year-old firefighter and paramedic is one of only six people who make up Dalzell’s volunteer-run fire department, and one of only two who lives in the town of about 660 residents in north-central Illinois, near Starved Rock State Park.

Justi raced to the station, jumped in an engine and drove, solo, to the man’s house. Once there, he quickly realized the man wasn’t breathing. Justi placed a device over the man’s nose and mouth and manually pumped oxygen into his lungs, continuing for at least five minutes until first responders from a neighboring town arrived to help.

The man survived. But, Justi reluctantly acknowledged, the outcome could have been different.

“If somebody wasn’t breathing for him, he would have been dead by the time the ambulance showed up,” Justi said.

“That was when we realized that we need some help here.”

Just over half of all firefighters in the United States are estimated to be volunteers: men and women who, like Justi, leave their homes and jobs at any moment to respond to house fires and car crashes, medical emergencies and natural disasters.

In Illinois, about two-thirds of the state’s roughly 1,100 fire departments rely almost entirely on volunteers.

And, with few exceptions, those departments are running out of volunteers.

The fluctuating ranks of volunteer departments make it difficult to accurately track the losses. But fire chiefs across Illinois say they’re facing historic staffing lows.

In Dalzell, the roster of six should be 16 to be fully staffed, said Chief Tom Riordan. Over in Divernon, in central Illinois, Chief Randy Rhodes said he’s lost eight volunteers just in the past two years. And the bylaws for the Galena Fire Department, billed as the state’s oldest, cap volunteer membership at 62. They’ve got 24, Chief Bob Conley said.

The alarming shortages come amid increased service demands driven by rising medical calls attributed largely to the state’s growing senior population.

As a result, departments are increasingly relying on surrounding agencies to aid in their emergency responses, while some chiefs have tapped into federal grant dollars to pay for part-time help to augment their aging rosters of existing volunteers.

“It’s going to become very critical, very shortly,” said Kevin Schott, an Illinois Firefighters Association board member. “The county and the state are going to need to look at this because the public safety is going to be impacted.”

Firefighting organizations and some state lawmakers have tried over the years to address the dearth of volunteers, offering tax breaks and other incentives aimed at buoying department ranks.

Those efforts have thus far found little success. And some department leaders fear the worst is yet to come.

If nothing changes, fire chiefs in Dalzell and elsewhere say they’ll no longer have enough people to answer medical calls, ceding that responsibility to neighboring agencies or private ambulance services. Other departments are looking at mergers as a way to hopefully prolong their survival.

All this could put hundreds of thousands of Illinois residents in the dangerous position of having to wait longer for help to arrive.

“A lot of people think when they call 911, help is going to be there,” said Jim Gielow, chief of the volunteer fire department in Pinckneyville, in southern Illinois. “They may not realize one day that won’t be the case.”

A long tradition, a slow decline

It wasn’t always like this.

Veteran fire chiefs wax nostalgic about decades past when the volunteer fire service thrived, ensconced in a centuries-old tradition (Ben Franklin is credited with creating the model with his Union Fire Company in Philadelphia) and encapsulated in a 1931 “The Saturday Evening Post” cover illustration by famed artist and chronicler of Americana, Norman Rockwell.

They had full rosters and waiting lists back then. They had generations of the same last names in their ranks, and high school “explorer” programs, like internships, that infused their departments with a youthful energy.

The residents of those communities, meanwhile, enjoyed fire protection without the costs of salaries and benefits, which freed up tax dollars for police and parks and roads.

The system worked, until it didn’t.

To be clear, the long, steady decline of the volunteer fire service isn’t unique to Illinois. Headlines across the country tell similar stories of depleted ranks

In 1995, there were an estimated 838,000 volunteer firefighters in America, according to figures from the National Fire Protection Association.

Twenty-five years later, that number fell to 676,900.

The ratio of volunteers per 1,000 people dropped by nearly 25% in that same time, estimates show.

There are plenty of explanations for the downfall.

One obvious factor is Illinois’ shrinking population. The state lost a little over 104,000 residents between 2021 and 2022, U.S. Census Bureau estimates show. The losses were felt in all but 11 of the 102 counties.

Some chiefs believe the sense of community pride and civic duty that once motivated people to volunteer has vanished.

“It just seems to be getting harder and harder to get the younger generation to step up and donate their time,” said Eric Lancaster, fire chief in the central Illinois town of Girard, population 1,785. “It’s definitely been a struggle. And it is definitely getting worse.”

And while it’s true that volunteerism has generally fallen over the last decades, a report earlier this year from the U.S. Census and AmeriCorps found that Illinois was one of only two states (Wyoming the other) that did not see a drop in the percentage of Americans who formally volunteered with organizations between 2017 and 2021 (Illinois’ formal volunteering percentage went from 28.1% to 28.3% in that time).

Changing economic conditions also play a role. Families are increasingly unable to survive on one income. And with fewer job opportunities in rural communities most dependent on volunteer firefighters, people are forced to travel farther to work for employers who aren’t always as willing to let their staff answer emergency calls.

Then there’s the simple reality that being a volunteer firefighter is demanding on the person and their families. Emergency pagers can go off during family dinners and at 2 a.m., on Christmas morning and at a school recital.

“There were times I missed things,” said Lt. Chris Garza, 48, a father of two who has volunteered with the Galena department for the past 13 years. “And you can’t get those moments back. But I know I’m helping somebody when they’re having the worst day possible.”

Others say the training requirements have made the volunteer fire service a hard sell. A basic firefighter certification can take around 180 hours to obtain, and though volunteer firefighters aren’t required to be certified, they do have to be trained to the state standard.

That means departments typically ask their members to attend weekly training sessions, usually one night a week.

Emergency medical training, also not required, can take another six months, and is often crucial given that medical calls account for about 70% of the incidents Illinois fire departments respond to each year.

“Guys get burned out after a while,” said Pinckneyville’s chief, Gielow. “They’re a little more on edge, working their full-time jobs and running a bunch of calls. It’s hard on their personal lives. It all kind of adds up.”

‘We can’t let off the accelerator’

On the last Monday of July, about 30 members of the Glen Ellyn Volunteer Fire Company gathered for a weekly training exercise. In this particular session, they wore full protective gear, face masks and oxygen tanks strapped to their backs, and waited for their turns to go inside an abandoned motel to rescue one of their own from a room filled with smoke billowing from a machine.

There was Vinh Lu, 50, a freelance film location scout and father who started volunteering with the fire department nearly five years ago because, like his military service, it gave him the chance to be part of something bigger.

Richard Arehart, 49, wanted to be a firefighter as a kid but instead became a banker. Nearly three years ago, he saw an online ad looking for volunteers and moved his family to Glen Ellyn so he could make his childhood dream come true.

Clare Doran, 53, went to a department open house seven years ago thinking she’d file paperwork or tidy up the office, only to realize the ask was to be a firefighter.

“I was like, I don’t think that’s a good idea. I don’t think I could carry anybody out,” Doran remembered. “And chief said, we’ll teach you. And they taught me.”

The west suburban fire department is one of the few in the Chicago area that still relies almost entirely on volunteers. And with about 60 members, it’s thus far managed to avoid the shortages that have plagued other volunteer departments. About 35 people showed up to a recruitment open house earlier this month, said Matt Andris, second assistant chief. Seven submitted applications to join, with more expected.

“I can’t put a finger on why we’re successful other than really hard work,” Andris said.

There are, of course, other contributing factors.

For one, the village has a separate, paid ambulance service. That means fire department volunteers aren’t required to go through more intensive emergency medical training, nor are they faced with the added strain of answering medical calls, which state data show have climbed by 35% in the last decade.

Unlike in rural parts of the state, Glen Ellyn’s 28,000 residents offer a large pool of potential volunteers, plenty of whom work in professions with flexible schedules that allow them more opportunity to donate their time. Some department members volunteer elsewhere. Doran, for example, volunteers with four other community groups.

The department also hired a Glen Ellyn-based marketing company to lead its recruitment efforts, which include targeted mailers, Google ad campaigns and volunteer profiles posted on the department’s website.

“We can’t let off the accelerator,” Chief Chris Clark said. “We have to continue to recruit the way we do. That’s just a fact for any volunteer organization.”

‘The bigger conversation is coming at us’

For the volunteer fire service to survive, recruitment needs to be the focus of every person in the department, said Steve Hirsch, a volunteer firefighter in Kansas and chair of the National Volunteer Fire Council.

“That’s our success,” he said. “It’s all those who wear red helmets out there recruiting friends and bringing names to us all the time.”

Departments also need to make sure their recruitment efforts are geared toward women and people of color, two groups that have historically been underrepresented in the fire service.

“We’ve not done a good job of recruiting in those communities,” Hirsch said of the fire service. “You’re overlooking half your population.”

It also takes money. The federal Staffing for Adequate Fire and Emergency Response grant program offers departments money for recruitment, retention and hiring. Since 2015, a little over 70 fire departments in Illinois received SAFER grants totaling close to $55 million.

Some departments use those federal dollars to pay volunteers a small stipend based on the number of calls they answered. Others have spent the money on part-time firefighters to answer calls during weekday hours when volunteer availability is especially limited.

Even Glen Ellyn, with its 60-member roster, still needs to augment its volunteer force by paying contractors to staff a fire engine during those hours.

But for some, the money’s not enough. They exist on fundraisers — 50/50 raffles, cookouts and craft fairs. They drive used fire engines donated by more fortunate peers and wear protective gear they can’t afford to replace despite it being too old by state standards.

Near the Quad Cities, the Colona Fire Department had hoped a federal grant could help it hire two people to cover daytime shifts in the town of 5,300 residents. Even with the money, the department couldn’t do it, Chief John Swan said.

“We’d have to pick up the tab after three years, and we can’t afford to do it,” said Swan, who noted that the department tried and failed last year to persuade residents to pass a tax increase to pay for daytime help.

“I have people in the department who are in their 50s and 60s that have to stay on because there’s no one available in the daytime,” he continued. “The public doesn’t understand. It just does not seem to sink in.”

Elected leaders in Springfield have passed bills in recent years aimed at giving volunteer departments a lift. One bill allowed volunteers to buy discounted tires for their personal vehicles at a government-discounted rate; another protects volunteers from being fired if they’re late to work or absent because of an emergency call.

This session, they passed a $500 tax credit for volunteer firefighters and a bill that allows state employees to leave work to attend firefighter training.

“Some of these bills look gimmicky,” said state Sen. Patrick Joyce, D-Essex, who sponsored the training bill. “But you have to throw something out there as a benefit. The bigger conversation is coming at us, and it’s going to be a lot of money.”

Lawmakers could pull from ideas generated 20 years ago, when Illinois fire department leaders and a bipartisan group of House members released separate reports on how to preserve the future of the state’s fire service.

Among the recommendations: Pass “pensionlike” legislation. Establish a life insurance and disability plan for volunteers. Create a scholarship program for volunteers and their families to attend Illinois universities and community colleges. Develop an incentive program for employers when their employees need to leave to answer emergency calls.

“I think you’re going to have a handful of firefighter bills every session from here to the end of time,” Joyce said. “You chip away at it and you try to address it.”

‘A dying tradition’

Their efforts might not be enough to save what Justi, the assistant chief in Dalzell, called “a dying tradition.”

In Peoria Heights, trustees in the town of 5,900 have been embroiled in an ongoing debate over the future of their volunteer fire department, which, like many, is short on volunteers.

After significant public pushback, trustees recently backtracked on a plan to offset that shortage by contracting help from the neighboring Peoria Fire Department, staffed by career firefighters.

What they do next will depend on whomever is picked as the next fire chief, said Matt Wigginton.

“There’s a lot of identity wrapped up in a local fire department,” Wigginton said. “But overarching, the biggest concern is public safety. At what point does that identity and nostalgia run up against public safety?”

Illinois already has a model program, called the Mutual Aid Box Alarm System (MABAS for short), that instantly dispatches help from neighboring fire departments when needed. Some fire chiefs think that system will become increasingly necessary for every call, no matter the severity.

“As much as anybody hates to have to call out to assist, I see it happening more and more now,” said Lancaster, the fire chief in Girard.

Others see a future where volunteer departments merge with their neighbors, hoping the combination of resources could free up enough money to pay people to offset dwindling volunteers.

But Swan, the chief in Colona, fears department consolidation will lead to longer response times.

Colona has a roster of 17 volunteers, Swan said, well below the 32 needed to be considered fully staffed.

“If nothing changes, there will be calls where we don’t show,” said Swan, who also serves as past president of the Illinois Firefighters Association.

It’s already happened, he said, medical calls at night that his department couldn’t answer because there was no one to respond.

“We have an ambulance backup, but minutes count,” he said.

If nothing changes in Divernon, Chief Rhodes said his department could no longer have the ability to respond to emergency medical calls. Those would then fall to neighboring towns and private ambulance services, both of which are also facing paramedic shortages.

A few high school seniors have expressed an interest in taking emergency medical classes and volunteering at the department. But that wouldn’t be until next summer, he said, and “we don’t know if we could hold it until then.”

Back in Dalzell, the forecast looks no better.

Two hospitals in the area closed this year — one in Peru, the other in Spring Valley — and the fallout has hit Dalzell and surrounding departments hard, exacerbating their staffing woes as ambulance crews are now tied up with longer transport times to and from hospitals.

Riordan, the fire chief, said they, too, might have to abandon medical calls.

“It’s the first thing that’s going to stop,” he said. “To be blunt, people are going to die because there’s nobody to take care of them.”

On a Thursday night in August, all six department members sat around a table in the fire station (also village hall) while Justi led a training on how to identify the types of hazardous materials that could be carried in the semitrailer trucks that lumber along Interstate 80 at the town’s northern border.

“Unfortunately, we’re not able to really mitigate the incident,” he told them. “Our job is to pretty much protect ourselves and everybody else that hasn’t been involved yet.”

All six said they were concerned about the department’s future and perplexed that no one in town seemed to care about the dire circumstances it faced.

“It’s really rough,” said Chris Mason, 44, a lieutenant who’s been with the department for nearly 17 years. “There’s not enough people to do anything.”

Later, they drove two fire engines and a water tanker truck — two of the three donated from other departments — to the elementary school parking lot to test hoses and engine pumps.

The first fire engine they tested, built in 1989, barely pumped water into its 500-gallon tank. It could be an easy fix, they hoped. If not, it could cost a few thousand dollars, money they can barely afford to spend.

During the testing, a man who lived nearby walked up to a few of the members. He’d been a volunteer years earlier but was asked to leave, he said, for missing too many training sessions.

He blamed his work schedule at the time. Now, standing in the grass as water sprayed from a fire hose attached to a nearby hydrant, he blamed the testing for turning the water at his house a funny color.

He asked them to stop, then turned and left.

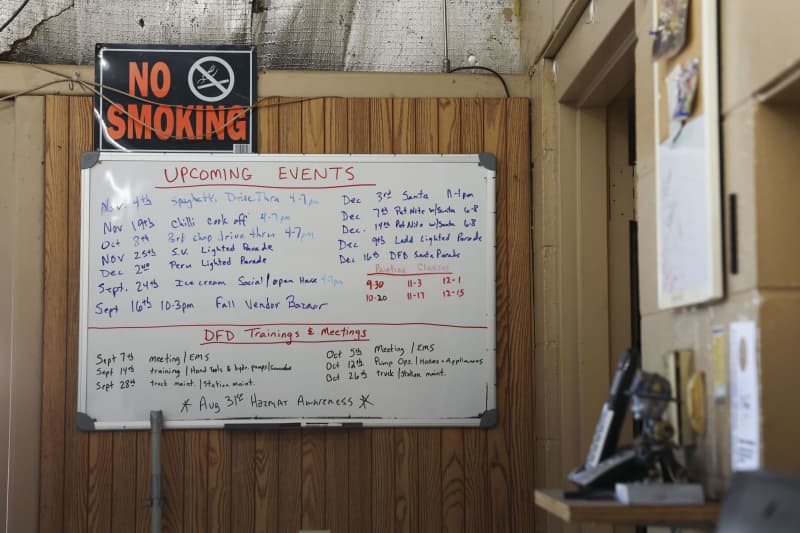

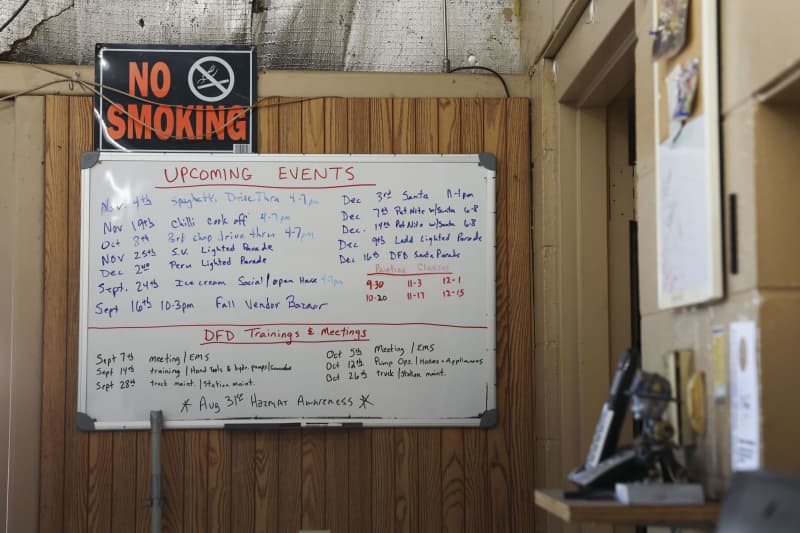

A list of upcoming fundraisers and training sessions are written on a whiteboard at the Dalzell fire station. - Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune/TNS

Glen Ellyn volunteer firefighters take a break after participating in a training at a vacant motel in Glen Ellyn on Aug. 30, 2023. - Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune/TNS

Kirk Huot speaks to other volunteer firefighters during the Glen Ellyn Volunteer Fire Company training on Aug. 30, 2023. - Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune/TNS

Assistant Chief Alex Justi helps test hoses and engine pumps in the Dalzell Grade School parking lot on Aug. 31, 2023. - Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune/TNS

Volunteer firefighter Chris Mason helps test hoses and engine pumps in the Dalzell Grade School parking lot on Aug. 31, 2023. - Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune/TNS

Assistant Chief Alex Justi helps test hoses and engine pumps in the Dalzell Grade School parking lot on Aug. 31, 2023. - Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune/TNS

© Chicago Tribune

© Chicago Tribune

No comments:

Post a Comment