REST IN POWER

Eddie Linden, illiterate Glasgow labourer who became an unlikely star of 1960s London’s poetry scene – obituaryTelegraph Obituaries

Tue, 5 December 2023

Eddie Linden: 'I’m a Glasgow Communist lapsed Catholic manic depressive bastard homosexual'

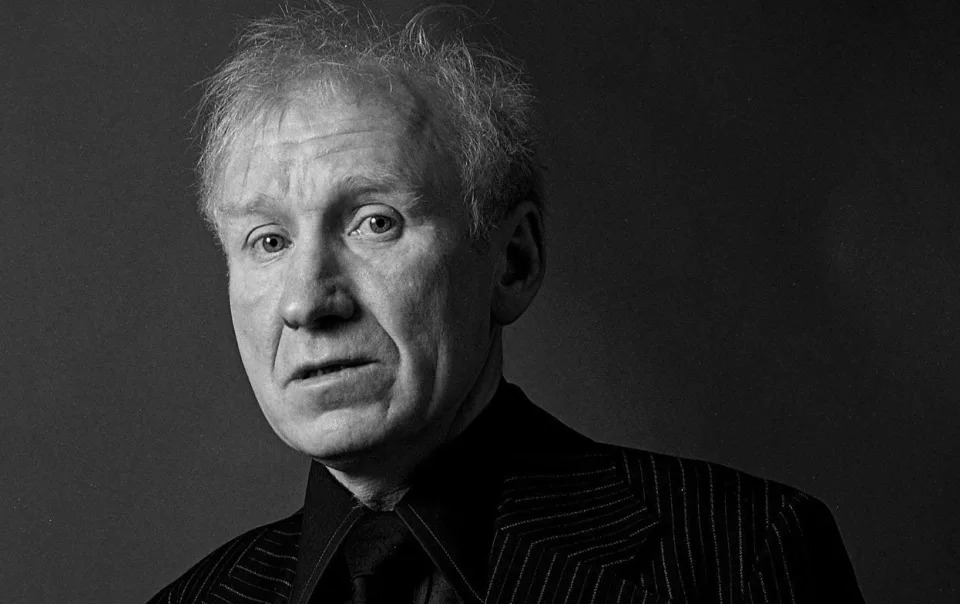

- Granville Davies

Eddie Linden, who has died aged 88, was a poet and poetry editor who combined persistence, loyalty and a complete lack of inhibition to persuade the most prominent poets of the late-20th century to contribute to his magazine, Aquarius.

Given his background, and his journey from illiteracy to literary London, this may have seemed unlikely; but among the poets of 1960s Soho and Fitzrovia, he found an open-minded and welcoming crowd. They provided him with a sense of family that he had never experienced as a child, even though he had searched for his real relatives, and had tried to find a different kind of kinship in the Communist Party and the Roman Catholic Church. His outbursts could provoke his most devoted supporters to rage and even violence, but he never saw his frankness as an obstacle to friendship.

His account of himself became familiar to those around him, but he would deliver it as if sharing a confidence: “I’m a Glasgow Communist lapsed Catholic manic depressive bastard homosexual.” This range of attributes, not least the last, gave him an entrée into artistic circles.

He would sometimes add Irish, working class and alcoholic into the mix. Some would dispute alcoholic, although he became integral to a poetry scene that centred on pubs, especially an old haunt of John Dryden’s, the Lamb and Flag in Holborn. There he would organise poetry readings so packed that the landlady expressed a fear that the ceiling would fall in.

When he launched Aquarius in 1969 with a party at Compendium bookshop in Camden, guests wondered who had paid for the drink. Linden would later explain that it came from a short stint working in a library, from which he had saved £70. The stint was short because he wanted to read to the children who visited the library, even though he had been employed as a porter. “I hated bosses,” he would recall of the episode. “I always liked to be my own man.”

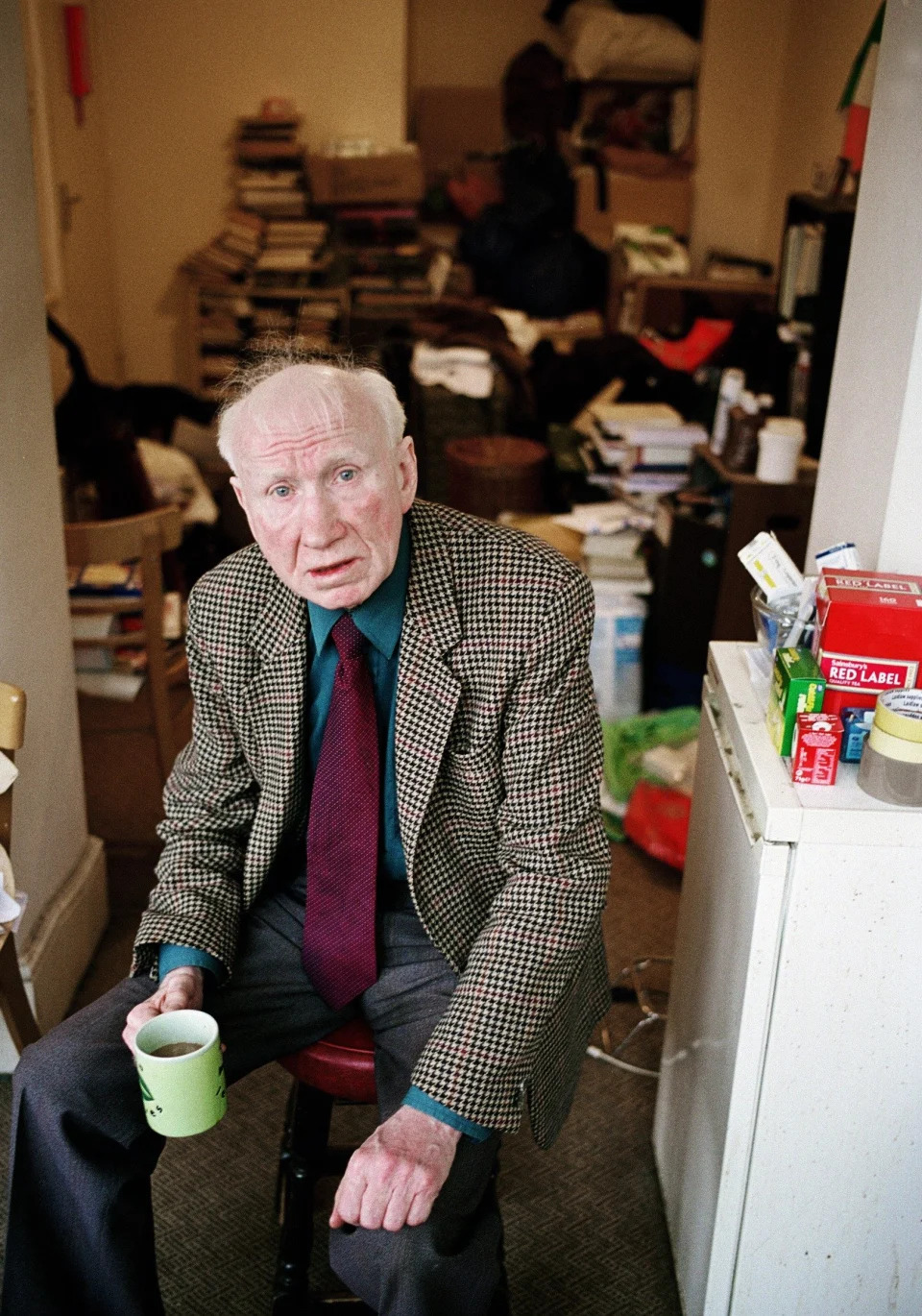

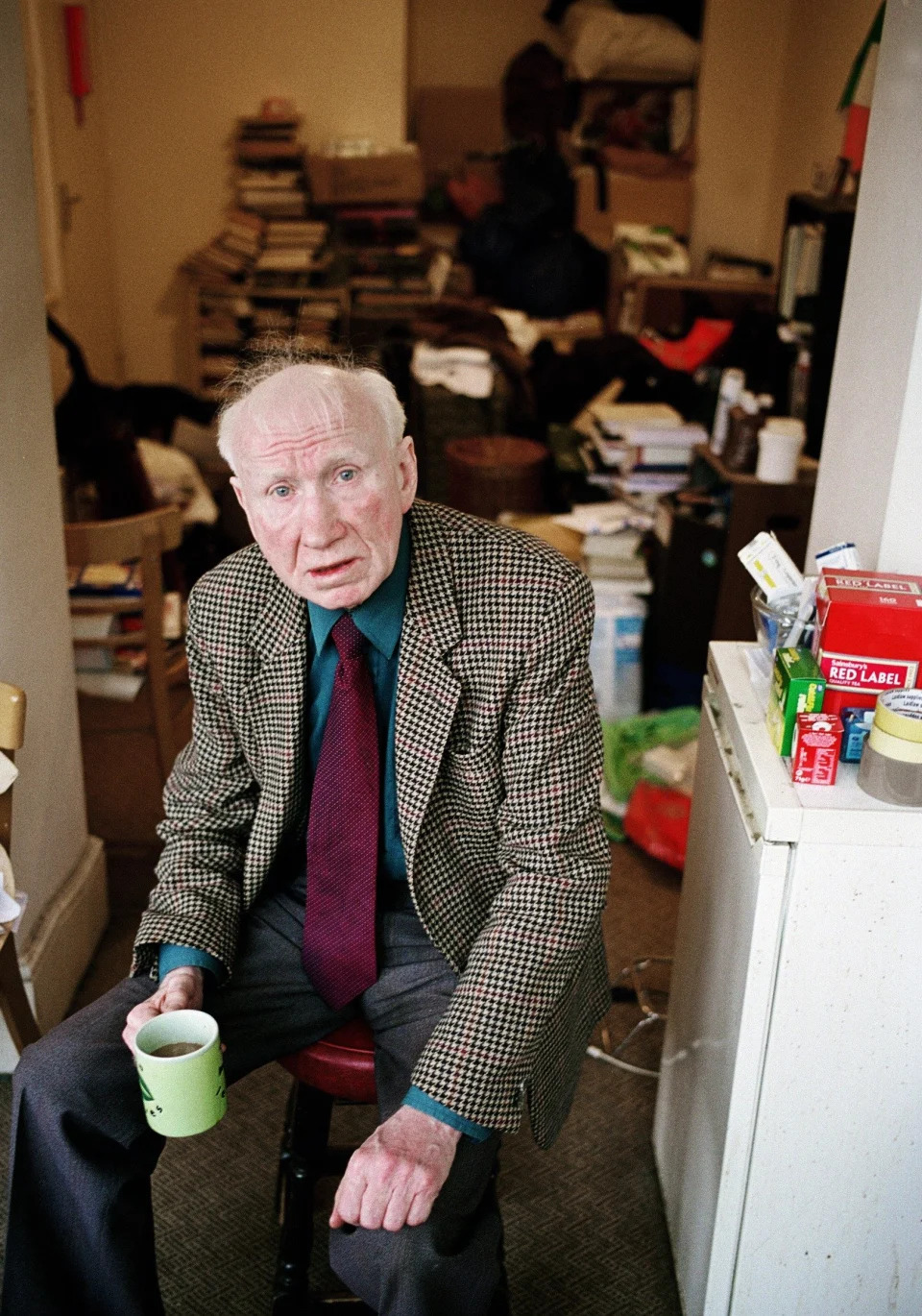

Eddie Linden, pictured in 2005, edited the poetry magazine Aquarius from 1969 to 2004 - Eamonn McCabe/Popperfoto

This was as true of jobs as it was of relationships and credos: he drifted away from Communism following the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956; his Catholicism survived the initial guilt he felt about his homosexuality, although in 1968 he was at the heart of a scuffle on the steps of Westminster Cathedral when he challenged worshippers who held up a banner in support of Pope Paul VI’s ruling against contraception.

His own poetry is straightforward and frank, and his best-known poems, such as “City of Razors” and “Hampstead at Night”, are the rough and rude ones. The former has been widely anthologised and translated, with its unflinching account of sectarian violence in Gorbals; the latter is one of many unambiguous, unornamented poems he wrote about sex.

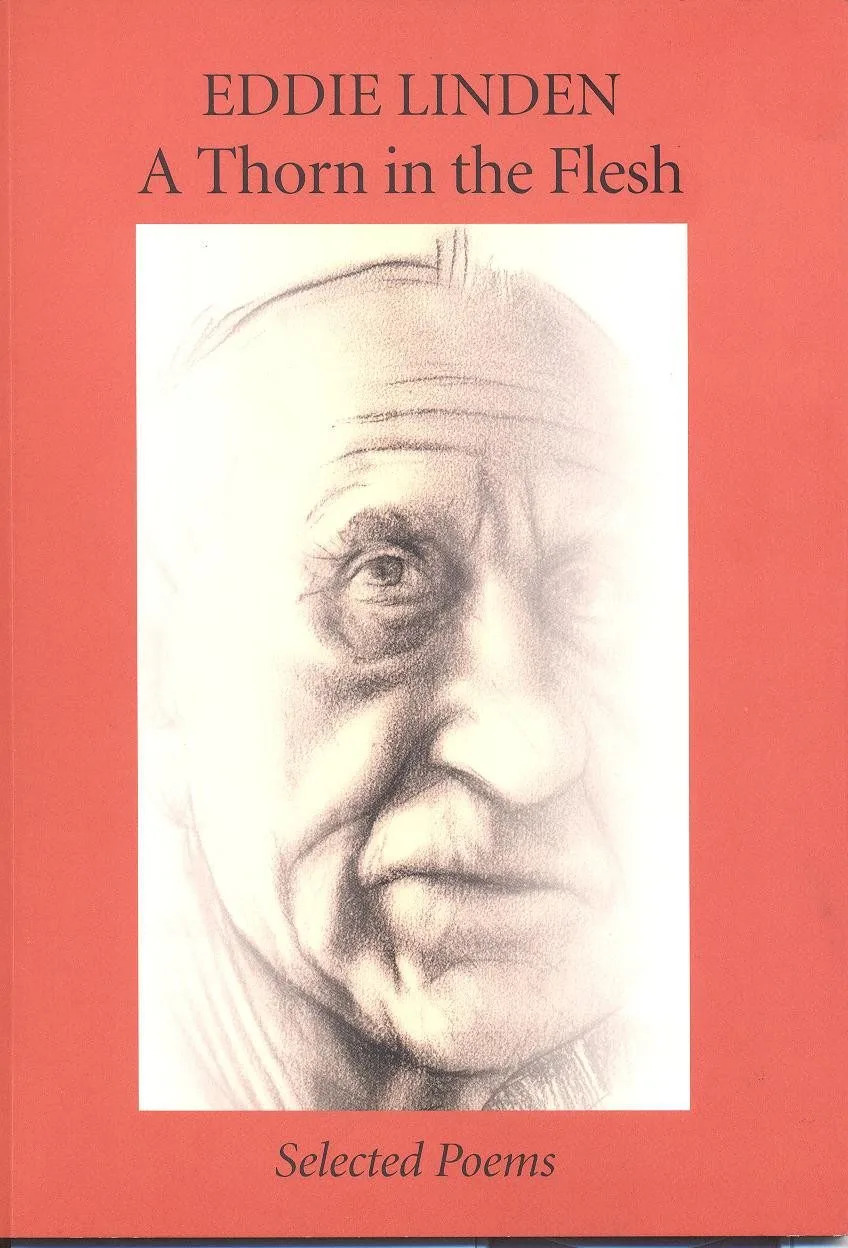

At other times, though, he could be mystical, even lyrical, and would recite his work in a kind of rapture, not always with much warning. The poems stayed easily in his memory, which he convincingly attributed to the legacy of Irish oral performance. There are two collections to his name: City of Razors and Other Poems (Jay Landesman, 1980); and A Thorn in the Flesh: Selected Poems (Hearing Eye, 2011).

As a curator of others’ work, he favoured the direct over the dry. Aquarius captured the mood of the late Sixties, with its freedom and boldness of expression. The first edition included work by George Barker and Stevie Smith, as well as the more surprising John Heath-Stubbs. Linden was a carer and companion to Heath-Stubbs, often acting as the latter’s “eyes” (glaucoma left Heath-Stubbs unable to read after 1961, and completely blind by 1978). They were a striking pair – one tall, the other short, one high Tory and evidently erudite, the other demotic and trenchantly Left-wing – but the loyalty ran deep: one issue of Aquarius was devoted to Heath-Stubbs’ poetry.

A Thorn in the Flesh

Eddie Linden was born John Edward Glackin on May 5 1935, in Motherwell, Lanarkshire. He would tell this differently, saying that he was born Sean Glackin, in Coalisland, Co Tyrone, moving to Motherwell a few months later. Certainly he was illegitimate, and his mother’s hasty move from Ireland was to avoid the disgrace. His birth parents were Joe Waters and Elizabeth Glackin. The Glackin family trade was carpentry.

In Motherwell, he was adopted by his uncle’s brother-in-law, Edward Linden, who was a coal miner. He and his wife Mary raised Eddie as a Roman Catholic in Bellshill. Mary died when Eddie was 8, and two years later, Edward married again, to perhaps the only person Eddie could never forgive.

His new stepmother didn’t want the boy, and tried to place him with his birth mother, who was now in Glasgow. This was unsuccessful (her new husband also did not want Eddie), and so was an attempt to put him in an asylum. He spent the next four years in an orphanage run by Roman Catholic nuns, attending the Holy Family School in Mossend, and then St Patrick’s in New Stevenston. He left school at 14. He was still barely able to read, much less write, at the age of 16.

He worked in a coalmine and a steel mill before becoming a railway porter and ticket inspector. This led him to join the railway union, and also the Young Communist League. The Communist Party provided the kind of education that he had lacked at school: it was not only political, but also cultural, and led Linden to literature, in particular Dickens, whose novel Oliver Twist made him feel he was reading about himself.

Trips to London as a Communist Party delegate enabled him to visit the theatre, in particular the plays of Arnold Wesker.

Linden’s commitment to Communism wavered, while his Catholicism lingered, in spite of his avowed difficulties with believe in God. It was sustained by a love of ritual. Seamus Heaney took some of Linden’s words in an interview, and turned them into a piece he called “A Found Poem”: there we hear Linden suggesting that words “like ‘thanksgiving’ or ‘host’ / or even ‘communion wafer’ … have an underlying / pallor and draw, like well water far down.”

Eddie Linden - Eamonn McCabe/Popperfoto

He still found his homosexuality troubling, and attempted medical intervention, but he fell out with the doctors. In 1958, he met Father Anthony Ross, a Dominican priest who would later become Rector of Edinburgh University, and who enabled Linden to reconcile these elements of his personality. One result was that he became active in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, carrying a Roman Catholic banner at the Aldermaston march of 1959. He also co-founded a charity for the homeless, the Simon Community, in 1963.

In 1966, he went to Plater College, for workers, linked to Oxford University. He left shortly afterwards, with a breakdown, but among others he met at Oxford was the writer Sebastian Barker. He would later write a biography, Who Is Eddie Linden, which also became a play starring the Scottish actor Michael Deacon. It was staged at the Old Red Lion in Islington; Linden saw it many times. By the mid-1960s, he was befriending other writers and poets, such as George Barker, John Heath-Stubbs and Derek Mahon. When Aquarius appeared, many of them contributed their poems for free, and also their editorial advice.

The magazine, which Linden produced from his small flat in Maida Vale, ran from 1969 until 2002; there were 26 issues. Linden was able to publish Seamus Heaney and Carol Ann Duffy early in their careers, when each had only one collection to their name. Aquarius readers included John Betjeman, who would send the publication £5 every Christmas; Harold Pinter, who was a financial backer and is thought to have based the character of Spooner in No Man’s Land on Linden; and the Conservative cabinet minister Kenneth Baker.

In 1991, fears that cash was running out led Brian Wilson MP to mention it in the House when asking about Arts Council funding. The then Arts Minister, Tim Renton, gave £2,000 to save the magazine. The last edition was in 2002, although a special Festschrift edition, called Eddie’s Own Aquarius, appeared in 2005, with tributes from Seamus Heaney, Elaine Feinstein, James Kelman, Bruce Kent, Andrew Motion and Clare Short.

Although tales of Linden’s drunkenness abound, he was proud to have gone through his last decades without alcohol.

Eddie Linden, born May 5 1935, died November 19 2023

Eddie Linden, who has died aged 88, was a poet and poetry editor who combined persistence, loyalty and a complete lack of inhibition to persuade the most prominent poets of the late-20th century to contribute to his magazine, Aquarius.

Given his background, and his journey from illiteracy to literary London, this may have seemed unlikely; but among the poets of 1960s Soho and Fitzrovia, he found an open-minded and welcoming crowd. They provided him with a sense of family that he had never experienced as a child, even though he had searched for his real relatives, and had tried to find a different kind of kinship in the Communist Party and the Roman Catholic Church. His outbursts could provoke his most devoted supporters to rage and even violence, but he never saw his frankness as an obstacle to friendship.

His account of himself became familiar to those around him, but he would deliver it as if sharing a confidence: “I’m a Glasgow Communist lapsed Catholic manic depressive bastard homosexual.” This range of attributes, not least the last, gave him an entrée into artistic circles.

He would sometimes add Irish, working class and alcoholic into the mix. Some would dispute alcoholic, although he became integral to a poetry scene that centred on pubs, especially an old haunt of John Dryden’s, the Lamb and Flag in Holborn. There he would organise poetry readings so packed that the landlady expressed a fear that the ceiling would fall in.

When he launched Aquarius in 1969 with a party at Compendium bookshop in Camden, guests wondered who had paid for the drink. Linden would later explain that it came from a short stint working in a library, from which he had saved £70. The stint was short because he wanted to read to the children who visited the library, even though he had been employed as a porter. “I hated bosses,” he would recall of the episode. “I always liked to be my own man.”

Eddie Linden, pictured in 2005, edited the poetry magazine Aquarius from 1969 to 2004 - Eamonn McCabe/Popperfoto

This was as true of jobs as it was of relationships and credos: he drifted away from Communism following the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956; his Catholicism survived the initial guilt he felt about his homosexuality, although in 1968 he was at the heart of a scuffle on the steps of Westminster Cathedral when he challenged worshippers who held up a banner in support of Pope Paul VI’s ruling against contraception.

His own poetry is straightforward and frank, and his best-known poems, such as “City of Razors” and “Hampstead at Night”, are the rough and rude ones. The former has been widely anthologised and translated, with its unflinching account of sectarian violence in Gorbals; the latter is one of many unambiguous, unornamented poems he wrote about sex.

At other times, though, he could be mystical, even lyrical, and would recite his work in a kind of rapture, not always with much warning. The poems stayed easily in his memory, which he convincingly attributed to the legacy of Irish oral performance. There are two collections to his name: City of Razors and Other Poems (Jay Landesman, 1980); and A Thorn in the Flesh: Selected Poems (Hearing Eye, 2011).

As a curator of others’ work, he favoured the direct over the dry. Aquarius captured the mood of the late Sixties, with its freedom and boldness of expression. The first edition included work by George Barker and Stevie Smith, as well as the more surprising John Heath-Stubbs. Linden was a carer and companion to Heath-Stubbs, often acting as the latter’s “eyes” (glaucoma left Heath-Stubbs unable to read after 1961, and completely blind by 1978). They were a striking pair – one tall, the other short, one high Tory and evidently erudite, the other demotic and trenchantly Left-wing – but the loyalty ran deep: one issue of Aquarius was devoted to Heath-Stubbs’ poetry.

A Thorn in the Flesh

Eddie Linden was born John Edward Glackin on May 5 1935, in Motherwell, Lanarkshire. He would tell this differently, saying that he was born Sean Glackin, in Coalisland, Co Tyrone, moving to Motherwell a few months later. Certainly he was illegitimate, and his mother’s hasty move from Ireland was to avoid the disgrace. His birth parents were Joe Waters and Elizabeth Glackin. The Glackin family trade was carpentry.

In Motherwell, he was adopted by his uncle’s brother-in-law, Edward Linden, who was a coal miner. He and his wife Mary raised Eddie as a Roman Catholic in Bellshill. Mary died when Eddie was 8, and two years later, Edward married again, to perhaps the only person Eddie could never forgive.

His new stepmother didn’t want the boy, and tried to place him with his birth mother, who was now in Glasgow. This was unsuccessful (her new husband also did not want Eddie), and so was an attempt to put him in an asylum. He spent the next four years in an orphanage run by Roman Catholic nuns, attending the Holy Family School in Mossend, and then St Patrick’s in New Stevenston. He left school at 14. He was still barely able to read, much less write, at the age of 16.

He worked in a coalmine and a steel mill before becoming a railway porter and ticket inspector. This led him to join the railway union, and also the Young Communist League. The Communist Party provided the kind of education that he had lacked at school: it was not only political, but also cultural, and led Linden to literature, in particular Dickens, whose novel Oliver Twist made him feel he was reading about himself.

Trips to London as a Communist Party delegate enabled him to visit the theatre, in particular the plays of Arnold Wesker.

Linden’s commitment to Communism wavered, while his Catholicism lingered, in spite of his avowed difficulties with believe in God. It was sustained by a love of ritual. Seamus Heaney took some of Linden’s words in an interview, and turned them into a piece he called “A Found Poem”: there we hear Linden suggesting that words “like ‘thanksgiving’ or ‘host’ / or even ‘communion wafer’ … have an underlying / pallor and draw, like well water far down.”

Eddie Linden - Eamonn McCabe/Popperfoto

He still found his homosexuality troubling, and attempted medical intervention, but he fell out with the doctors. In 1958, he met Father Anthony Ross, a Dominican priest who would later become Rector of Edinburgh University, and who enabled Linden to reconcile these elements of his personality. One result was that he became active in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, carrying a Roman Catholic banner at the Aldermaston march of 1959. He also co-founded a charity for the homeless, the Simon Community, in 1963.

In 1966, he went to Plater College, for workers, linked to Oxford University. He left shortly afterwards, with a breakdown, but among others he met at Oxford was the writer Sebastian Barker. He would later write a biography, Who Is Eddie Linden, which also became a play starring the Scottish actor Michael Deacon. It was staged at the Old Red Lion in Islington; Linden saw it many times. By the mid-1960s, he was befriending other writers and poets, such as George Barker, John Heath-Stubbs and Derek Mahon. When Aquarius appeared, many of them contributed their poems for free, and also their editorial advice.

The magazine, which Linden produced from his small flat in Maida Vale, ran from 1969 until 2002; there were 26 issues. Linden was able to publish Seamus Heaney and Carol Ann Duffy early in their careers, when each had only one collection to their name. Aquarius readers included John Betjeman, who would send the publication £5 every Christmas; Harold Pinter, who was a financial backer and is thought to have based the character of Spooner in No Man’s Land on Linden; and the Conservative cabinet minister Kenneth Baker.

In 1991, fears that cash was running out led Brian Wilson MP to mention it in the House when asking about Arts Council funding. The then Arts Minister, Tim Renton, gave £2,000 to save the magazine. The last edition was in 2002, although a special Festschrift edition, called Eddie’s Own Aquarius, appeared in 2005, with tributes from Seamus Heaney, Elaine Feinstein, James Kelman, Bruce Kent, Andrew Motion and Clare Short.

Although tales of Linden’s drunkenness abound, he was proud to have gone through his last decades without alcohol.

Eddie Linden, born May 5 1935, died November 19 2023

No comments:

Post a Comment