Could Venezuela's aims to seize a chunk of its neighbor lead to war?

Patrick J. McDonnell, MERY MOGOLLÓN

Thu, December 14, 2023

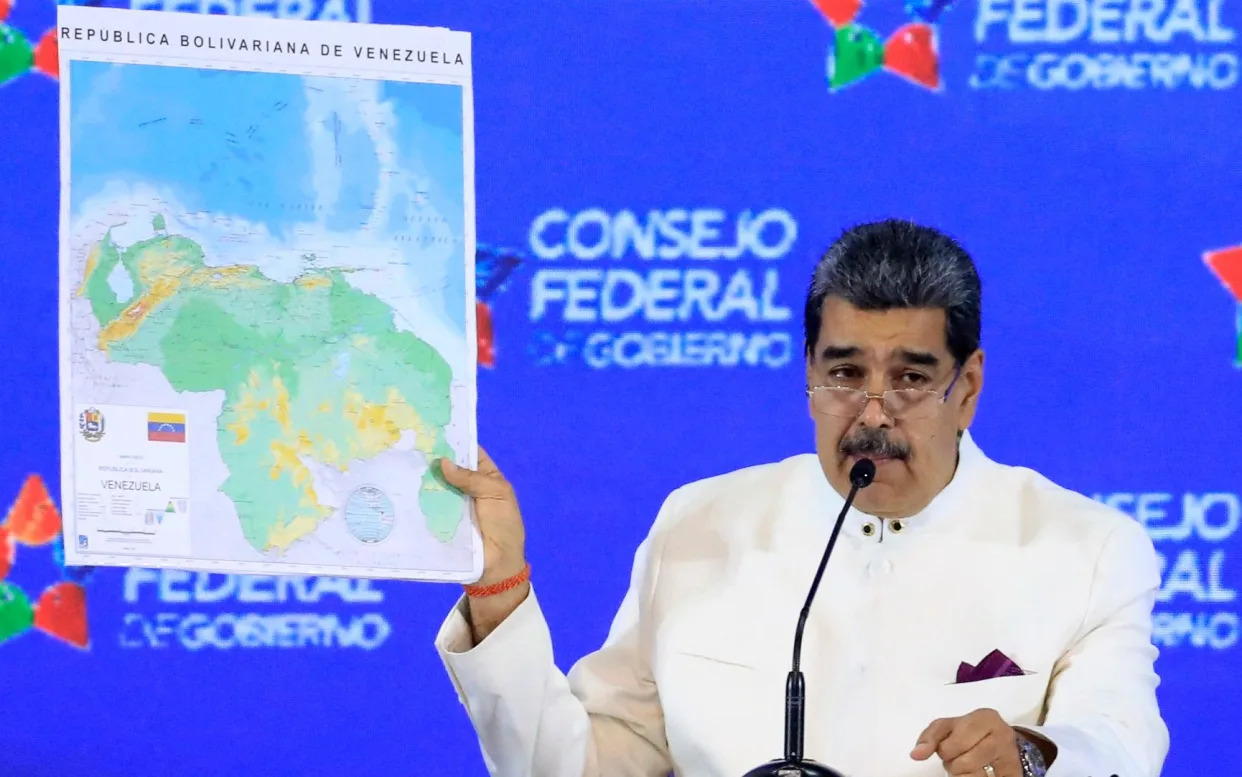

Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro speaks to supporters after a referendum this month on Venezuela's claim to the Essequibo region of Guyana.

What's the backdrop behind the dispute?

Venezuela is home to some of the world’s largest oil reserves. But its once-robust economy cratered and millions of impoverished Venezuelans have emigrated, especially since the 2017 mass protests against the rule of the socialist Maduro, a protege of ex-President Hugo Chávez and a fervent adversary of the United States.

Maduro blames his country’s woes on U.S. sanctions that have helped cripple Venezuela’s petroleum sector. Washington calls Maduro an authoritarian dictator whose mismanagement has wrecked Venezuela’s economy and battered the country’s oil-and-gas extraction infrastructure — and caused misery for many of the country's 30.5 million residents.

In Caracas, a boy drives a motorbike in front of a mural of the Venezuelan map with the Essequibo region of Guyana included.

What is Essequibo?

The sprawling swath of jungle, savanna and coast known as Essequibo — for the Essequibo River that forms its eastern boundary — accounts for two-thirds of Guyana's land. At 61,000 square miles, it's an area slightly smaller than Florida.

The border dispute with Venezuela dates to the early 1800s and British Guiana, as pre-independence Guyana was known. An 1899 international arbitration decision affirmed that Essequibo was part of British Guiana, but Venezuela has long said the process was rigged and that its dominion over Essequibo stretches back centuries to Spanish colonial days. Guyana gained independence in 1966.

Read more: Guyana's president says his country is preparing to defend itself against Venezuela

The Essequibo area, rich in timber and minerals, is now helping to transform Guyana through the recent oil boom.

In 2018, with an offshore drilling frenzy well underway, Guyana moved to secure an international imprimatur for control of Essequibo, taking its case to the International Court of Justice (sometimes called the World Court), the United Nations' highest judicial panel. Last April, the court rejected procedural objections from Caracas, paving the way for the justices to hear arguments from both sides.

What steps has Venezuela taken?

The World Court ruling stung Venezuelan officials, who feared the panel would ultimately declare Essequibo part of Guyana — even though a final decision is probably years off.

Maduro was left with "a ball of fire in his hands," said Jesús Seguías, an independent political analyst in Caracas.

Appearing on the verge of losing Essequibo would be a humiliation for a president already on shaky electoral ground, said Seguías.

But Maduro, a survivor of the Trump administration "maximum pressure" campaign to drive him from office, struck back. He called a nationwide referendum on a plan to incorporate Essequibo into Venezuela and deny World Court jurisdiction.

The International Court of Justice on Dec. 1 ordered Venezuela not to do anything to alter the status quo on Guyana’s control over Essequibo. But it denied Guyana's bid to ban the referendum.

The Essequibo River flows in Guyana. Venezuela wants to annex Guyana's oil- and mineral-rich Essequibo region. (Juan Pablo Arraez / Associated Press)

Many analysts saw Maduro's moves as a ploy ahead of next year's elections.

"This is really about Venezuelan domestic politics," said Geoff Ramsey, a senior analyst with the Atlantic Council, a Washington-based think tank. "Maduro is trying to make up for falling popularity by stoking nationalism."

The Venezuelan government said more than 95% of voters approved the referendum. But images of sparsely attended polling stations led many to question the official account that 10 million people cast ballots.

Read more: Efforts to squelch democracy in Venezuela are increasing, U.N. rights experts say

Among those voting was Carlos Herrera, 60, a Caracas plumber who agreed that Essequibo belonged to Venezuela — but said the matter should be resolved peacefully. "Maduro will do whatever he can to avoid confronting the country's real problems," Herrera said. "Poverty is our main problem. One doesn't win wars with hunger."

Following the vote, Maduro unveiled an expansive blueprint for a new Venezuelan state of Essequibo, ordered Venezuela’s state energy and mineral concerns to begin preparations to work there, and launched the process to grant Venezuelan citizenship to the region's 125,000, mostly English-speaking residents. He presented a multicolored map incorporating the disputed territory inside Venezuela's boundaries.

Venezuela dispatched a military contingent to the Atlantic coast, close to the disputed area, and named a major-general as provisional authority in the area.

Although Maduro gave companies working in Essequibo three months to leave, Exxon Mobil declared Tuesday on its Guyana Facebook page: "We are not going anywhere."

Read more: Guyana agrees to talks with Venezuela over territorial dispute under pressure from Brazil, others

How has Guyana responded?

Guyana’s leadership has denounced what it calls an illegal land grab threatening regional stability. President Ali labeled Venezuela an "outlaw nation" and stressed that his country would seek outside aid to thwart any more provocations from Caracas.

"Should Venezuela proceed to act in this reckless and adventurous manner, the region will have to respond," Ali told the Associated Press.

How have other countries reacted?

U.S. Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken reaffirmed Washington’s position that Guyana has full sovereignty over Essequibo. The U.S. military's Southern Command said it would conduct flight operations in collaboration with Guyana’s military — a move denounced as a “provocation” by Caracas.

Brazil, which shares northern borders with Venezuela and Guyana, said it was bolstering its military presence along its northern frontiers.

Read more: Venezuelan immigrants are ostracized in Colombia amid xenophobia and shifting politics

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who has tried to broker a solution, declared: "What we don't want here in South America is war.”

Some observers suspect Maduro could be seeking a pretext to declare a national emergency and call off next year's election.

Is military action by Venezuela a realistic possibility?

Most observers say Venezuela is unlikely to launch a military strike. Even though its 100,000-plus troops far outnumber Guyana's meager defense array, the logistical hurdles are considerable: A full-scale ground invasion is not practical, experts say, since much of the Essequibo frontier with Venezuela is near-impenetrable rain forest and swamps. That leaves the faint possibility of an air or marine assault.

A Venezuelan attack could trigger an armed response from allies of Guyana. It would also probably further isolate Venezuela when Caracas is agreeing to electoral reforms and cooperating with Washington on immigration strategy in a near-desperate effort to convince the White House to relax sanctions. The oil boom next door in Guyana has dramatized how much Venezuela needs outside expertise and investment to revitalize its own oil industry.

"Neither Venezuela or Guyana want to see this expand into a full-blown conflict," Ramsey said. "This is much more about saber-rattling than a real threat."

What's next?

There is little expectation that Thursday's meeting between Maduro and Ali will yield anything close to a resolution amid so much bad blood and tortured history.

Even after the bilateral session was announced, Ali stated again that his country’s land boundaries were not up for discussion. And Caracas reiterated its “unquestionable rights of sovereignty” over Essequibo.

"It's very unlikely that we see either Venezuela or Guyana reach a substantial agreement," Ramsey said. "But what we are likely to see is a de-escalation in rhetoric."

McDonnell reported from Mexico City and special correspondent Mogollón from Caracas.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

Can Caribbean meeting cool border dispute between leaders of Venezuela and Guyana?

Jacqueline Charles

Thu, December 14, 2023

The leaders of Venezuela and Guyana are scheduled to meet face to face Thursday in the eastern Caribbean, but Guyanese President Irfaan Ali is making it clear that “the high-level” dialogue with Nicolás Maduro will not be a negotiation over the fate of an oil-rich territory that his country has controlled for more than a century.

Ali says his intention in attending the meeting is to deescalate the conflict, as called for by his fellow Caribbean Community leaders, between his nation and Venezuela.

The crisis erupted between the two contentious neighbor earlier this month when Venezuela reactivated its claim over the disputed Essequibo region in Guayana and announced moves to annex it. Roughly the size of Florida, the 61,776 square mile region represents a major chunk of Guyana and was the subject of an 1899 decision by international arbitrators, who placed its control under what was then British Guiana.

The meeting on Thursday is being held in St. Vincent, the main island of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, under the auspices of the 15-member Caribbean Community regional bloc known as CARICOM and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, CELAC. St. Vincent and the Grenadines Prime Minister Ralph Gonsalves is a member of CARICOM and currently serves as president of CELAC. He is also one of the Caribbean’s most vocal supporters of lifting U.S. sanctions against Venezuela. Brazil President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was also expected to participate, but reportedly will now be represented instead by his foreign relations adviser, Celso Amorin.

Also attending will be Courtenay Rattray, the chief of staff for United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres, and Miroslav Jenča, the assistant secretary-general for Europe, Central Asia and the Americas, Guterres spokesman Stéphane Dujarric said. Dujarric said the invitation was extended by Gonsalves for the U.N. to attend as observers.

“The secretary-general welcomes the announcement of the meeting of the presidents of Guyana and Venezuela,” Dujarric said, adding that Guterres commends the efforts by da Silva and Gonsalves to bring the two sides together, and the support expressed by Mexico and the international community.

“The Secretary-General trusts this meeting will result in an immediate de-escalation of the tensions and calls on the parties to settle their differences through peaceful means, in accordance with the U.N. charter and international law.... The controversy is before the International Court of Justice and the secretary-general does not take a position in relation to ongoing judicial proceedings.”

The region has been on edge ever since Maduro reactivated his claims on the Essequibo.

Maduro claims that in a Dec. 3 referendum, 95% of Venezuelan voters rejected the United Nations International Court of Justice’s jurisdiction over the border dispute, and gave him approval to create a new state that he is now calling Guayana Esequiba.

Some independent observers have disputed Maduro’s election-turnout claims, while security analysts say that the Venezuelan leader’s increased rhetoric and contentious claims on the region are an attempt to put another item on the table in negotiations with the United States. Washington, which has long accused Maduro of undermining democracy in Venezuela, as of late has been pressuring him to release American hostages “wrongly detained” by his government and lift bans that keep opponents who want to run for president from serving in office. Maduro has so far failed to comply and some experts believe he is using Guyana as an excuse to impose martial law in Venezuela ahead of next year’s anticipated presidential elections that if free and fair could see him ousted from office.

“The land boundary is not a matter for bilateral discussion and the settlement of the matter is properly in the International Court of Justice where it must remain until the court gives its final ruling on the merits of the case, which Guyana has always said and I repeat, will be fully respected by Guyana,” Ali wrote in a letter to Gonsalves ahead of the Thursday meeting.

Ali says he was responding to statements made by Maduro that the purpose of the dialogue between the two was “in order to directly address the territorial dispute between Venezuela and Guyana.” The comments were made in a Dec. 11 letter from Maduro to Gonsalves, which the former shared on X, formerly Twitter.

“I welcome direct, face-to-face talks,” Maduro posted. “It has always been my proposal, for I believe in dialogue, candid conversation, understanding and peaceful coexistence between peoples and nations. I will attend the meeting with the mandate given to me by the people. Venezuela shall overcome.”

It’s unclear what, if anything, will emerge from the talks.

The brewing crisis has become a major headache for both South American and Caribbean Community leaders, who have have had conflicting views of Maduro. As a group, leaders last week reiterated their support for Guyana and urged Venezuela “to respect” the international court’s Dec. 1 ruling for the borders to remain as they are until a final resolution is determined by the court.

CARICOM also called for “a de-escalation of the conflict and for appropriate dialogue between the leaders of Venezuela and Guyana to ensure peaceful coexistence, the application and respect for international law and the avoidance of the use or threats of force.”

Bahamas Prime Minister Philip Davis went further in a separate statement.

“I am disheartened that after all that CARICOM has done to protect the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela during a most trying economic and political period in its history that Venezuela should now seek to annex territory in a CARICOM state,” Davis said.

Ahead of hosting the talks, Gonsalves, who often refers to Maduro as “comrade” and “brother,” said he wanted to avoid threats of force and reminded both leaders that they are on record as being committed to having the Caribbean be a zone of peace.

Miami Herald data reporter Ana Claudia Chacin contributed to this story.

Patrick J. McDonnell, MERY MOGOLLÓN

Thu, December 14, 2023

Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro speaks to supporters after a referendum this month on Venezuela's claim to the Essequibo region of Guyana.

(Matias Delacroix / Associated Press

Is armed conflict on the horizon in the northern hinterlands of South America?

The prospect of a military confrontation has emerged in recent weeks as Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro has threatened to annex a chunk of resource-rich land in neighboring Guyana. The vast territory has been a source of a contention for more than a century.

Maduro's claims on the region — which Venezuelans call Guayana Esequiba and Guyanese call Essequibo — come as he faces unpopularity at home and growing international pressure to hold clean elections next year.

This month, Maduro put the territorial demands on Guyana to a vote in a domestic referendum — a bid to harness nationalist sentiment in a nation where generations of schoolchildren have been taught that the contested terrain is an essential part of Venezuela.

The conflict has alarmed the United Nations, the United States, Brazil and other nations. And now Maduro and Guyana’s president, Mohamed Irfaan Ali, are scheduled to meet Thursday in the Caribbean island-nation of St. Vincent and the Grenadines. All sides profess to favor a peaceful resolution.

Here are the details:

Is armed conflict on the horizon in the northern hinterlands of South America?

The prospect of a military confrontation has emerged in recent weeks as Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro has threatened to annex a chunk of resource-rich land in neighboring Guyana. The vast territory has been a source of a contention for more than a century.

Maduro's claims on the region — which Venezuelans call Guayana Esequiba and Guyanese call Essequibo — come as he faces unpopularity at home and growing international pressure to hold clean elections next year.

This month, Maduro put the territorial demands on Guyana to a vote in a domestic referendum — a bid to harness nationalist sentiment in a nation where generations of schoolchildren have been taught that the contested terrain is an essential part of Venezuela.

The conflict has alarmed the United Nations, the United States, Brazil and other nations. And now Maduro and Guyana’s president, Mohamed Irfaan Ali, are scheduled to meet Thursday in the Caribbean island-nation of St. Vincent and the Grenadines. All sides profess to favor a peaceful resolution.

Here are the details:

What's the backdrop behind the dispute?

Venezuela is home to some of the world’s largest oil reserves. But its once-robust economy cratered and millions of impoverished Venezuelans have emigrated, especially since the 2017 mass protests against the rule of the socialist Maduro, a protege of ex-President Hugo Chávez and a fervent adversary of the United States.

Maduro blames his country’s woes on U.S. sanctions that have helped cripple Venezuela’s petroleum sector. Washington calls Maduro an authoritarian dictator whose mismanagement has wrecked Venezuela’s economy and battered the country’s oil-and-gas extraction infrastructure — and caused misery for many of the country's 30.5 million residents.

In Caracas, a boy drives a motorbike in front of a mural of the Venezuelan map with the Essequibo region of Guyana included.

(Matias Delacroix / Associated Press)

Guyana, a staunch U.S. ally, is a former Dutch and British colony that is home to a small but extremely diverse population of 800,000 — including descendants of African slaves and indentured workers from the Asian subcontinent, Indigenous peoples and settlers from Europe and elsewhere. It is the sole nation on the continent where English is the official language.

Read more: Venezuelans approve referendum to claim sovereignty over much of neighboring Guyana, officials say

Guyana is perhaps best-known in the United States as the site of the 1978 murder-suicide of more than 900 people linked to the California-based Peoples Temple cult and its wayward leader, Jim Jones.

Guyana's economy long featured relatively small-scale farming, fishing, timber-harvesting and mining. But the once-quiescent economy has been super-charged since discoveries in 2015 of huge offshore oil deposits.

Guyana, a staunch U.S. ally, is a former Dutch and British colony that is home to a small but extremely diverse population of 800,000 — including descendants of African slaves and indentured workers from the Asian subcontinent, Indigenous peoples and settlers from Europe and elsewhere. It is the sole nation on the continent where English is the official language.

Read more: Venezuelans approve referendum to claim sovereignty over much of neighboring Guyana, officials say

Guyana is perhaps best-known in the United States as the site of the 1978 murder-suicide of more than 900 people linked to the California-based Peoples Temple cult and its wayward leader, Jim Jones.

Guyana's economy long featured relatively small-scale farming, fishing, timber-harvesting and mining. But the once-quiescent economy has been super-charged since discoveries in 2015 of huge offshore oil deposits.

What is Essequibo?

The sprawling swath of jungle, savanna and coast known as Essequibo — for the Essequibo River that forms its eastern boundary — accounts for two-thirds of Guyana's land. At 61,000 square miles, it's an area slightly smaller than Florida.

The border dispute with Venezuela dates to the early 1800s and British Guiana, as pre-independence Guyana was known. An 1899 international arbitration decision affirmed that Essequibo was part of British Guiana, but Venezuela has long said the process was rigged and that its dominion over Essequibo stretches back centuries to Spanish colonial days. Guyana gained independence in 1966.

Read more: Guyana's president says his country is preparing to defend itself against Venezuela

The Essequibo area, rich in timber and minerals, is now helping to transform Guyana through the recent oil boom.

In 2018, with an offshore drilling frenzy well underway, Guyana moved to secure an international imprimatur for control of Essequibo, taking its case to the International Court of Justice (sometimes called the World Court), the United Nations' highest judicial panel. Last April, the court rejected procedural objections from Caracas, paving the way for the justices to hear arguments from both sides.

What steps has Venezuela taken?

The World Court ruling stung Venezuelan officials, who feared the panel would ultimately declare Essequibo part of Guyana — even though a final decision is probably years off.

Maduro was left with "a ball of fire in his hands," said Jesús Seguías, an independent political analyst in Caracas.

Appearing on the verge of losing Essequibo would be a humiliation for a president already on shaky electoral ground, said Seguías.

But Maduro, a survivor of the Trump administration "maximum pressure" campaign to drive him from office, struck back. He called a nationwide referendum on a plan to incorporate Essequibo into Venezuela and deny World Court jurisdiction.

The International Court of Justice on Dec. 1 ordered Venezuela not to do anything to alter the status quo on Guyana’s control over Essequibo. But it denied Guyana's bid to ban the referendum.

The Essequibo River flows in Guyana. Venezuela wants to annex Guyana's oil- and mineral-rich Essequibo region. (Juan Pablo Arraez / Associated Press)

Many analysts saw Maduro's moves as a ploy ahead of next year's elections.

"This is really about Venezuelan domestic politics," said Geoff Ramsey, a senior analyst with the Atlantic Council, a Washington-based think tank. "Maduro is trying to make up for falling popularity by stoking nationalism."

The Venezuelan government said more than 95% of voters approved the referendum. But images of sparsely attended polling stations led many to question the official account that 10 million people cast ballots.

Read more: Efforts to squelch democracy in Venezuela are increasing, U.N. rights experts say

Among those voting was Carlos Herrera, 60, a Caracas plumber who agreed that Essequibo belonged to Venezuela — but said the matter should be resolved peacefully. "Maduro will do whatever he can to avoid confronting the country's real problems," Herrera said. "Poverty is our main problem. One doesn't win wars with hunger."

Following the vote, Maduro unveiled an expansive blueprint for a new Venezuelan state of Essequibo, ordered Venezuela’s state energy and mineral concerns to begin preparations to work there, and launched the process to grant Venezuelan citizenship to the region's 125,000, mostly English-speaking residents. He presented a multicolored map incorporating the disputed territory inside Venezuela's boundaries.

Venezuela dispatched a military contingent to the Atlantic coast, close to the disputed area, and named a major-general as provisional authority in the area.

Although Maduro gave companies working in Essequibo three months to leave, Exxon Mobil declared Tuesday on its Guyana Facebook page: "We are not going anywhere."

Read more: Guyana agrees to talks with Venezuela over territorial dispute under pressure from Brazil, others

How has Guyana responded?

Guyana’s leadership has denounced what it calls an illegal land grab threatening regional stability. President Ali labeled Venezuela an "outlaw nation" and stressed that his country would seek outside aid to thwart any more provocations from Caracas.

"Should Venezuela proceed to act in this reckless and adventurous manner, the region will have to respond," Ali told the Associated Press.

How have other countries reacted?

U.S. Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken reaffirmed Washington’s position that Guyana has full sovereignty over Essequibo. The U.S. military's Southern Command said it would conduct flight operations in collaboration with Guyana’s military — a move denounced as a “provocation” by Caracas.

Brazil, which shares northern borders with Venezuela and Guyana, said it was bolstering its military presence along its northern frontiers.

Read more: Venezuelan immigrants are ostracized in Colombia amid xenophobia and shifting politics

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who has tried to broker a solution, declared: "What we don't want here in South America is war.”

Some observers suspect Maduro could be seeking a pretext to declare a national emergency and call off next year's election.

Is military action by Venezuela a realistic possibility?

Most observers say Venezuela is unlikely to launch a military strike. Even though its 100,000-plus troops far outnumber Guyana's meager defense array, the logistical hurdles are considerable: A full-scale ground invasion is not practical, experts say, since much of the Essequibo frontier with Venezuela is near-impenetrable rain forest and swamps. That leaves the faint possibility of an air or marine assault.

A Venezuelan attack could trigger an armed response from allies of Guyana. It would also probably further isolate Venezuela when Caracas is agreeing to electoral reforms and cooperating with Washington on immigration strategy in a near-desperate effort to convince the White House to relax sanctions. The oil boom next door in Guyana has dramatized how much Venezuela needs outside expertise and investment to revitalize its own oil industry.

"Neither Venezuela or Guyana want to see this expand into a full-blown conflict," Ramsey said. "This is much more about saber-rattling than a real threat."

What's next?

There is little expectation that Thursday's meeting between Maduro and Ali will yield anything close to a resolution amid so much bad blood and tortured history.

Even after the bilateral session was announced, Ali stated again that his country’s land boundaries were not up for discussion. And Caracas reiterated its “unquestionable rights of sovereignty” over Essequibo.

"It's very unlikely that we see either Venezuela or Guyana reach a substantial agreement," Ramsey said. "But what we are likely to see is a de-escalation in rhetoric."

McDonnell reported from Mexico City and special correspondent Mogollón from Caracas.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

Can Caribbean meeting cool border dispute between leaders of Venezuela and Guyana?

Jacqueline Charles

Thu, December 14, 2023

The leaders of Venezuela and Guyana are scheduled to meet face to face Thursday in the eastern Caribbean, but Guyanese President Irfaan Ali is making it clear that “the high-level” dialogue with Nicolás Maduro will not be a negotiation over the fate of an oil-rich territory that his country has controlled for more than a century.

Ali says his intention in attending the meeting is to deescalate the conflict, as called for by his fellow Caribbean Community leaders, between his nation and Venezuela.

The crisis erupted between the two contentious neighbor earlier this month when Venezuela reactivated its claim over the disputed Essequibo region in Guayana and announced moves to annex it. Roughly the size of Florida, the 61,776 square mile region represents a major chunk of Guyana and was the subject of an 1899 decision by international arbitrators, who placed its control under what was then British Guiana.

The meeting on Thursday is being held in St. Vincent, the main island of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, under the auspices of the 15-member Caribbean Community regional bloc known as CARICOM and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, CELAC. St. Vincent and the Grenadines Prime Minister Ralph Gonsalves is a member of CARICOM and currently serves as president of CELAC. He is also one of the Caribbean’s most vocal supporters of lifting U.S. sanctions against Venezuela. Brazil President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was also expected to participate, but reportedly will now be represented instead by his foreign relations adviser, Celso Amorin.

Also attending will be Courtenay Rattray, the chief of staff for United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres, and Miroslav Jenča, the assistant secretary-general for Europe, Central Asia and the Americas, Guterres spokesman Stéphane Dujarric said. Dujarric said the invitation was extended by Gonsalves for the U.N. to attend as observers.

“The secretary-general welcomes the announcement of the meeting of the presidents of Guyana and Venezuela,” Dujarric said, adding that Guterres commends the efforts by da Silva and Gonsalves to bring the two sides together, and the support expressed by Mexico and the international community.

“The Secretary-General trusts this meeting will result in an immediate de-escalation of the tensions and calls on the parties to settle their differences through peaceful means, in accordance with the U.N. charter and international law.... The controversy is before the International Court of Justice and the secretary-general does not take a position in relation to ongoing judicial proceedings.”

The region has been on edge ever since Maduro reactivated his claims on the Essequibo.

Maduro claims that in a Dec. 3 referendum, 95% of Venezuelan voters rejected the United Nations International Court of Justice’s jurisdiction over the border dispute, and gave him approval to create a new state that he is now calling Guayana Esequiba.

Some independent observers have disputed Maduro’s election-turnout claims, while security analysts say that the Venezuelan leader’s increased rhetoric and contentious claims on the region are an attempt to put another item on the table in negotiations with the United States. Washington, which has long accused Maduro of undermining democracy in Venezuela, as of late has been pressuring him to release American hostages “wrongly detained” by his government and lift bans that keep opponents who want to run for president from serving in office. Maduro has so far failed to comply and some experts believe he is using Guyana as an excuse to impose martial law in Venezuela ahead of next year’s anticipated presidential elections that if free and fair could see him ousted from office.

“The land boundary is not a matter for bilateral discussion and the settlement of the matter is properly in the International Court of Justice where it must remain until the court gives its final ruling on the merits of the case, which Guyana has always said and I repeat, will be fully respected by Guyana,” Ali wrote in a letter to Gonsalves ahead of the Thursday meeting.

Ali says he was responding to statements made by Maduro that the purpose of the dialogue between the two was “in order to directly address the territorial dispute between Venezuela and Guyana.” The comments were made in a Dec. 11 letter from Maduro to Gonsalves, which the former shared on X, formerly Twitter.

“I welcome direct, face-to-face talks,” Maduro posted. “It has always been my proposal, for I believe in dialogue, candid conversation, understanding and peaceful coexistence between peoples and nations. I will attend the meeting with the mandate given to me by the people. Venezuela shall overcome.”

It’s unclear what, if anything, will emerge from the talks.

The brewing crisis has become a major headache for both South American and Caribbean Community leaders, who have have had conflicting views of Maduro. As a group, leaders last week reiterated their support for Guyana and urged Venezuela “to respect” the international court’s Dec. 1 ruling for the borders to remain as they are until a final resolution is determined by the court.

CARICOM also called for “a de-escalation of the conflict and for appropriate dialogue between the leaders of Venezuela and Guyana to ensure peaceful coexistence, the application and respect for international law and the avoidance of the use or threats of force.”

Bahamas Prime Minister Philip Davis went further in a separate statement.

“I am disheartened that after all that CARICOM has done to protect the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela during a most trying economic and political period in its history that Venezuela should now seek to annex territory in a CARICOM state,” Davis said.

Ahead of hosting the talks, Gonsalves, who often refers to Maduro as “comrade” and “brother,” said he wanted to avoid threats of force and reminded both leaders that they are on record as being committed to having the Caribbean be a zone of peace.

Miami Herald data reporter Ana Claudia Chacin contributed to this story.

Guyana and Venezuela leaders to meet face-to-face as region pushes to defuse territorial dispute

Associated Press

Wed, December 13, 2023

Venezuela's new map that includes the Essequibo territory as its own is displayed at the Foreign Ministry in Caracas, Venezuela, Monday, Dec. 11, 2023. Leaders of Guyana and Venezuela are preparing to meet this week to address an escalating dispute over the Essequibo region that is rich in oil and minerals.

(AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

GEORGETOWN, Guyana (AP) — The leaders of Guyana and Venezuela headed for a tense meeting Thursday as regional nations sought to defuse a long-standing territorial dispute that has escalated with Venezuelans voting in a referendum to claim two-thirds of their smaller neighbor.

Pushed by regional partners, Guyanan President Irfaan Ali and Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro agreed to meet at the Argyle International airport on the eastern Caribbean island of St. Vincent. The prime ministers of Barbados, Dominica and Trinidad and Tobago said they also would attend.

The meeting is aimed at easing the tensions that have flared over Essequibo, a vast border region rich in oil and minerals that represents much of Guyana's territory but that Venezuela claims as its own.

Venezuela’s president followed the referendum by ordering his state-owned companies to explore and exploit the oil, gas and mines in Essequibo. And both sides have put their militaries on alert.

It was unclear if the session would lead to any agreements or even ease the border controversy.

Guyana’s president has repeatedly said the dispute needs to be resolved solely by the International Court of Justice in the Netherlands.

“We are firm on this matter and it will not be open for discussion,” Ali wrote Tuesday on X, formerly known as Twitter.

Venezuela insists the Essequibo region was part of its territory during the Spanish colonial period, and argues the 1966 Geneva Agreement between their country, Britain and Guyana, the former colony of British Guiana, nullified the border drawn in 1899 by international arbitrators.

In a letter sent Tuesday to Ralph Gonsalves, prime minister of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Guyana’s president said the Geneva Agreement states that the International Court of Justice should settle any border controversy.

Ali also said he was concerned about what he described as “inaccurate assertions” made by Maduro’s own letter to Gonsalves.

He rebutted Maduro’s description of oil concessions granted by Guyana as being “in a maritime area yet to be delimited." Ali said all oil blocks “are located well within Guyanese waters under international law, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.”

Ali also rejected what he said Maduro described as “meddling of the United States Southern Command, which has begun operations in the disputed territory.”

The U.S. Southern Command conducted flight operations within Guyana in recent days.

“Any allegation that a military operation aimed at Venezuela exists in any part of Guyanese territory is false, misleading and provocative,” Ali said in his letter to Gonsalves.

Maduro's letter to Gonsalves repeats Venezuela's contention that the border drawn in 1899 was “the result of a scheme” between the U.S. and the U.K. It also said the dispute “must be amicably resolved in a matter acceptable to both parties.”

Maduro also referred to the Dec. 3 referendum on Venezuela claiming ownership of Essequibo, which has vast oil deposits off its coast.

The meeting between the two leaders was scheduled to last one day, although many expect the disagreement to drag on into next year.

Guyana president calls Venezuela's Maduro an 'outlaw' in border dispute

GEORGETOWN, Guyana (AP) — The leaders of Guyana and Venezuela headed for a tense meeting Thursday as regional nations sought to defuse a long-standing territorial dispute that has escalated with Venezuelans voting in a referendum to claim two-thirds of their smaller neighbor.

Pushed by regional partners, Guyanan President Irfaan Ali and Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro agreed to meet at the Argyle International airport on the eastern Caribbean island of St. Vincent. The prime ministers of Barbados, Dominica and Trinidad and Tobago said they also would attend.

The meeting is aimed at easing the tensions that have flared over Essequibo, a vast border region rich in oil and minerals that represents much of Guyana's territory but that Venezuela claims as its own.

Venezuela’s president followed the referendum by ordering his state-owned companies to explore and exploit the oil, gas and mines in Essequibo. And both sides have put their militaries on alert.

It was unclear if the session would lead to any agreements or even ease the border controversy.

Guyana’s president has repeatedly said the dispute needs to be resolved solely by the International Court of Justice in the Netherlands.

“We are firm on this matter and it will not be open for discussion,” Ali wrote Tuesday on X, formerly known as Twitter.

Venezuela insists the Essequibo region was part of its territory during the Spanish colonial period, and argues the 1966 Geneva Agreement between their country, Britain and Guyana, the former colony of British Guiana, nullified the border drawn in 1899 by international arbitrators.

In a letter sent Tuesday to Ralph Gonsalves, prime minister of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Guyana’s president said the Geneva Agreement states that the International Court of Justice should settle any border controversy.

Ali also said he was concerned about what he described as “inaccurate assertions” made by Maduro’s own letter to Gonsalves.

He rebutted Maduro’s description of oil concessions granted by Guyana as being “in a maritime area yet to be delimited." Ali said all oil blocks “are located well within Guyanese waters under international law, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.”

Ali also rejected what he said Maduro described as “meddling of the United States Southern Command, which has begun operations in the disputed territory.”

The U.S. Southern Command conducted flight operations within Guyana in recent days.

“Any allegation that a military operation aimed at Venezuela exists in any part of Guyanese territory is false, misleading and provocative,” Ali said in his letter to Gonsalves.

Maduro's letter to Gonsalves repeats Venezuela's contention that the border drawn in 1899 was “the result of a scheme” between the U.S. and the U.K. It also said the dispute “must be amicably resolved in a matter acceptable to both parties.”

Maduro also referred to the Dec. 3 referendum on Venezuela claiming ownership of Essequibo, which has vast oil deposits off its coast.

The meeting between the two leaders was scheduled to last one day, although many expect the disagreement to drag on into next year.

Guyana president calls Venezuela's Maduro an 'outlaw' in border dispute

Suzanne Gamboa and Tom Llamas and Ignacio Torres

Updated Wed, December 13, 2023

A day before their scheduled meeting, Guyana President Mohamed Irfaan Ali called Venezuela President Nicolás Maduro an "outlaw" who is "acting recklessly" in trying to wrest oil-rich land from Guyana.

In an interview Wednesday with NBC News Now anchor Tom Llamas, Ali reacted to recent comments by Maduro that Venezuela "immediately will proceed to give operating licenses for the exploration and exploitation of oil, gas and mines in our Guayana Essequibo."

"President Maduro is reckless in that statement. It shows he is an outlaw," Ali said.

Venezuela was ordered last week by the United Nation's International Court of Justice (ICJ) to refrain from any changes to the status quo in the Essequibo region of Guyana. Maduro claimed sovereignty over neighboring Guyana's Essequibo region — where oil was found in 2015 — after a questionable referendum. Ali said the issue should be decided by the ICJ.

A day before their scheduled meeting, Guyana President Mohamed Irfaan Ali called Venezuela President Nicolás Maduro an "outlaw" who is "acting recklessly" in trying to wrest oil-rich land from Guyana.

In an interview Wednesday with NBC News Now anchor Tom Llamas, Ali reacted to recent comments by Maduro that Venezuela "immediately will proceed to give operating licenses for the exploration and exploitation of oil, gas and mines in our Guayana Essequibo."

"President Maduro is reckless in that statement. It shows he is an outlaw," Ali said.

Venezuela was ordered last week by the United Nation's International Court of Justice (ICJ) to refrain from any changes to the status quo in the Essequibo region of Guyana. Maduro claimed sovereignty over neighboring Guyana's Essequibo region — where oil was found in 2015 — after a questionable referendum. Ali said the issue should be decided by the ICJ.

Guyana President Mohamed Irfaan Ali arrives at the Canada-CARICOM summit in Ottawa in October. (Sean Kilpatrick / The Canadian Press via AP)

As Venezuela has threatened to defy the order, the two nations have been moving forces to their shared border.

Maduro and Ali are scheduled to meet Thursday on the Caribbean island of St. Vincent for bilateral talks. But Ali said he plans to state clearly to Maduro that "Essequibo belongs to Guyana. That we are not exiting the ICJ. That there is no, absolutely no, negotiations on the issue of Essequibo."

Asked if he would give up some land in the Essequibo region, Ali responded "not a single inch."

"Essequibo belongs to Guyana. We are not giving up a single inch, not even in thought or idea, much less physical," Ali said.

The interview aired Wednesday on “Top Story with Tom Llamas” at 7 p.m. ET on NBC News Now.

Essequibo has been in Guyana for centuries, when the boundary for the country was drawn by an international commission.

Although the boundary for Essequibo as Guyana territory was drawn in 1899, Venezuela has said the drawing was unfairly drawn by Americans and Europeans. Venezuela's oil industry has tanked under Maduro's administration.

Ali said Venezuela's actions have parallels to Russia's invasion of Ukraine and those in the Western Hemisphere should not allow it.

"We cannot tolerate this type of reckless behavior in the Western Hemisphere. It has no place here," he said. Maduro has been calling the refusal of Guyana to give up land in the region, which is about two-thirds of the country, an American agenda and imperialism, Ali said.

An Exxon-Mobil consortium first discovered the oil deposits and is the country's largest producer of oil.

"This is absolute nonsense. Was that imperialism when Exxon was investing in Venezuela. Why wasn't it imperialist then?" he asked.

Ali said he thinks Venezuela is capable of "acting recklessly and in a manner that can destabilize the peace that exists within this region" but he added, "we are not afraid because we know we are starting on the right side of international law. We're standing on the right side of history. We're standing on the right side of facts."

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com

Venezuela's President Nicolas Maduro

Venezuela may not launch full-scale Guyana invasion, but could do something just as dangerous | Opinion

Andres Oppenheimer

Wed, December 13, 2023

1

Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro is not likely to launch a full-scale military invasion of Guyana’s disputed Esequibo region, as he tacitly threatened in a speech this month. But he may launch a “silent invasion,” which could be just as dangerous.

According to this theory, Maduro may send a small team of soldiers to a remote region of the oil-rich Esequibo jungle, and plant a Venezuelan flag. Then, he would release a video of the scene and request that Russia and China ask the United Nations to call for a “cessation of hostilities” in the area. This, in effect, would establish a de facto Venezuelan presence there.

Such an action most likely would trigger an international conflict and give Maduro a “national emergency” excuse to cancel next year’s elections in Venezuela, many experts suspect.

In his televised address to the nation on Dec. 5, Maduro held a map titled “New map of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela” that includes the Esequibo area and announced plans to create a new Venezuelan state there. He called it the “Guayana Esequiba.”

Maduro also said he would grant Venezuela’s state oil firm PDVSA licenses to explore oil deposits in the area, which makes up about three-quarters of Guyana’s territory.

In a Dec. 8 article with the headline “The entirely manufactured and dangerous crisis over the Esequibo,” Ryan Berg, director of Washington’s Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Latin America program, speculated that Maduro may engage in “hybrid warfare” or start a silent invasion. “The entirely manufactured and dangerous crisis over the Esequibo.”

Berg argued that Maduro has several “opportunities for hybrid warfare or gray zone tactics,” because “the Esequibo area is enormous (a third larger than the areas of Ukraine currently occupied by Russia), sparsely inhabited and comprised of dense jungle.”

According to Berg, “Maduro might seek to send a small contingency of Venezuelan soldiers into Guyana, plant a flag, then claim that these forces are protecting the newly created state of Guayana Esequiba.”

Asked for more specifics, Berg told me that Maduro may not even need to send soldiers to the Esequibo jungle: The Venezuelan dictator could fake the event.

“Maduro could tape a video in Venezuelan territory, in an area similar to Guyana’s, with Venezuelan soldiers talking about defending their territory,” Berg told me. “Nobody would be able to tell whether it was taped in Venezuela or Guyana.”

Berg says Maduro may not launch a full-blown invasion because Venezuelan armed forces “are better understood as a drug-trafficking organization rather than a proper fighting force.” But he does not rule out an invasion, because, “Dictators do not always choose the ‘rational’ option.”

Most Venezuelans, including top opposition leaders, support their country’s long-contended claim to the Esequibo region. The area was awarded to Guyana in a Paris arbitration decision in 1899, but Venezuela formally repudiated the Paris award in 1962.

Juan Guaidó, the former Venezuelan interim president appointed by the now-dissolved opposition-controlled National Assembly, agrees that a full-scale Venezuelan invasion is unlikely.

“Maduro doesn’t have the capacity even to provide gasoline, water, energy, basic services. He wouldn’t be able to sustain a conventional war,” Guaidó told me. “But I don’t rule out that he would plant a flag, or do something like that, to divert as attention from Venezuela’s domestic problems and provoke an international conflict.”

Indeed, Maduro knows that he is in deep trouble. He is scheduled to run for re-election in 2024, and a recent ORC poll gave him a dismal 14% popularity rate. Meantime, the opposition held a highly successful primary in October, in which hard-liner Maria Corina Machado won with 93% of the vote. That injected new energy into the opposition movement.

Politically cornered, Maduro may create a national emergency to postpone the elections or eliminate the few remaining political freedoms n Venezuela. A military invasion of Guyana would be too risky and could mark the beginning of the end of his regime, as happened when Argentina’s military junta invaded the British-held Falkland/Malvinas islands in 1982.

I wouldn’t be surprised if he opts for planting a Venezuelan flag in the jungle, and turns that episode — real or fake — into a larger international conflict.

Far from Venezuela-Guyana oil flap, Mango Landing just wants peace

Patrick FORT

Wed, December 13, 2023

Two Venezuelans rest at their home in Mango Landing in Guyana

(ROBERTO CISNEROS)

Robinson Flores, a Venezuelan who has been living in Essequibo for years, has no time for politicians fighting over the disputed oil-rich region run by Guyana.

Life in this sleepy border village along the muddy Wenamu River is just fine, thank you, he says. And the flap that exploded in recent months as Venezuela lays claim to Essequibo is an unwelcome disruption.

"Politicians do their thing and we pay for the damage," said Flores, a 52-year-old merchant.

Mango Landing sits smack in the middle of the jungle, a stone's throw from Venezuela, just across the river. And it is a far cry from the maelstrom of geostrategic jockeying now under way as Guyana defends its century-old control over Essequibo and Venezuela maneuvers to take it away.

"Indigenous people, Brazilians, Venezuelans and, of course, Guyanans, we all live together in peace," said Doriely Garcia, a 30-year-old chef whose partner is an Indigenous man with Guyanese nationality.

The lone police station in Mango Landing has been beefed up in recent weeks with more officers.

The village is the gateway to Essequibo but is more oriented toward Venezuela. It takes a boat ride of several days to reach the Guyana capital of Georgetown, but in just about an hour on the water you can hit the closest road in Venezuela.

"Everything that arrives here comes from Venezuela: food, fuel, medicine, clothes," said Flores. If the border were to close, he said, "it would strangle us. Venezuelans and Guyanans."

A machete wound on his left calf is covered with a bandage treated with a homemade remedy using vinegar and bacterial cream and applied with adhesive tape.

"Here we got by with what we have," said Flores.

The Essequibo dispute goes like this: President Nicolas Maduro of Venezuela has revived a decades-old claim on the region which makes up more than two-thirds of Guyana's territory, since a huge oil find in Essequibo waters came in 2015.

Essequibo has been administered by Guyana for more than a century and is the subject of border litigation before the International Court of Justice in The Hague. It is home to 125,000 of the country's 800,000 citizens.

In some ways Mango Landing looks like a ghost town, with abandoned wooden houses overtaken by hungry, lush vegetation.

People come and go as gold fever lures fortune seekers. But in just a few years the settlement's population has fallen from 400 or 500 to around just 100, most of them Venezuelans.

The exodus is happening because gold at the surface of the earth -- 'oro facil' in Spanish -- as opposed to gold that requires hard digging, is much more scarce.

Another reason for the decline in population is Venezuela's economic implosion, with runaway inflation and shortages of food, medicine and things as basic as soap and toilet paper.

"The economic crisis moved here. Prices have shot up," said Flores.

People who pan or dig for gold do not always make it, as costs run too high to make it profitable. Many hang it up, and leave, giving Mango Landing a disheveled, abandoned look.

The political crisis between Venezuela and Guyana has made things worse.

Since the dispute erupted in September, the price of gasoline in Mango Landing has shot up $2 per liter to $6. A tin of tuna costs $5, and a bottle of Coke goes for more than $7.

- 'No governments help us'

Part of the problem is Venezuelan soldiers who demand bribes to let stuff into Guyana and now demand more money, residents speaking on condition of anonymity said.

"Before we would pay the Venezuelan soldiers, and the syndicates, and the police here," one Venezuelan miner said. Syndicates are crime gangs. "But now there are more military posts, and they demand more money."

"It was a good life up until now but now everything is expensive," said Cindy Francis, a 33-year-old Guyanese who is married to a miner. The couple moved from Georgetown to Mango Landing about 10 years ago.

Francis said she does not care if Essequibo is part of Guyana or Venezuela. "We have to think about maintaining our family. No governments help us," she said, sitting in her home next to a portrait of President Irfaan Ali.

When she sees Venezuelan police on the river she waves, just as she does with local cops in the village. "We are all humans," said Francis.

Milton Shaomeer Ali, a 64-year-old shop owner, says business is very slow. "Now I don't have many customers. One this morning, one two days ago." He said everything depends on mining.

"We need good relations between the politics and the economics," he said.

ExxonMobil (XOM) Remains in Guyana Despite Venezuela Dispute

Robinson Flores, a Venezuelan who has been living in Essequibo for years, has no time for politicians fighting over the disputed oil-rich region run by Guyana.

Life in this sleepy border village along the muddy Wenamu River is just fine, thank you, he says. And the flap that exploded in recent months as Venezuela lays claim to Essequibo is an unwelcome disruption.

"Politicians do their thing and we pay for the damage," said Flores, a 52-year-old merchant.

Mango Landing sits smack in the middle of the jungle, a stone's throw from Venezuela, just across the river. And it is a far cry from the maelstrom of geostrategic jockeying now under way as Guyana defends its century-old control over Essequibo and Venezuela maneuvers to take it away.

"Indigenous people, Brazilians, Venezuelans and, of course, Guyanans, we all live together in peace," said Doriely Garcia, a 30-year-old chef whose partner is an Indigenous man with Guyanese nationality.

The lone police station in Mango Landing has been beefed up in recent weeks with more officers.

The village is the gateway to Essequibo but is more oriented toward Venezuela. It takes a boat ride of several days to reach the Guyana capital of Georgetown, but in just about an hour on the water you can hit the closest road in Venezuela.

"Everything that arrives here comes from Venezuela: food, fuel, medicine, clothes," said Flores. If the border were to close, he said, "it would strangle us. Venezuelans and Guyanans."

A machete wound on his left calf is covered with a bandage treated with a homemade remedy using vinegar and bacterial cream and applied with adhesive tape.

"Here we got by with what we have," said Flores.

The Essequibo dispute goes like this: President Nicolas Maduro of Venezuela has revived a decades-old claim on the region which makes up more than two-thirds of Guyana's territory, since a huge oil find in Essequibo waters came in 2015.

Essequibo has been administered by Guyana for more than a century and is the subject of border litigation before the International Court of Justice in The Hague. It is home to 125,000 of the country's 800,000 citizens.

In some ways Mango Landing looks like a ghost town, with abandoned wooden houses overtaken by hungry, lush vegetation.

People come and go as gold fever lures fortune seekers. But in just a few years the settlement's population has fallen from 400 or 500 to around just 100, most of them Venezuelans.

The exodus is happening because gold at the surface of the earth -- 'oro facil' in Spanish -- as opposed to gold that requires hard digging, is much more scarce.

Another reason for the decline in population is Venezuela's economic implosion, with runaway inflation and shortages of food, medicine and things as basic as soap and toilet paper.

"The economic crisis moved here. Prices have shot up," said Flores.

People who pan or dig for gold do not always make it, as costs run too high to make it profitable. Many hang it up, and leave, giving Mango Landing a disheveled, abandoned look.

The political crisis between Venezuela and Guyana has made things worse.

Since the dispute erupted in September, the price of gasoline in Mango Landing has shot up $2 per liter to $6. A tin of tuna costs $5, and a bottle of Coke goes for more than $7.

- 'No governments help us'

Part of the problem is Venezuelan soldiers who demand bribes to let stuff into Guyana and now demand more money, residents speaking on condition of anonymity said.

"Before we would pay the Venezuelan soldiers, and the syndicates, and the police here," one Venezuelan miner said. Syndicates are crime gangs. "But now there are more military posts, and they demand more money."

"It was a good life up until now but now everything is expensive," said Cindy Francis, a 33-year-old Guyanese who is married to a miner. The couple moved from Georgetown to Mango Landing about 10 years ago.

Francis said she does not care if Essequibo is part of Guyana or Venezuela. "We have to think about maintaining our family. No governments help us," she said, sitting in her home next to a portrait of President Irfaan Ali.

When she sees Venezuelan police on the river she waves, just as she does with local cops in the village. "We are all humans," said Francis.

Milton Shaomeer Ali, a 64-year-old shop owner, says business is very slow. "Now I don't have many customers. One this morning, one two days ago." He said everything depends on mining.

"We need good relations between the politics and the economics," he said.

ExxonMobil (XOM) Remains in Guyana Despite Venezuela Dispute

Zacks Equity Research

Wed, December 13, 2023

Despite the escalating territorial dispute with neighboring Venezuela, Exxon Mobil Corporation XOM intends to continue increasing production in offshore Guyana, per a report by AP news. Venezuela asserts its ownership of the oil-rich region.

ExxonMobil is reiterating its steadfast, long-term commitment to Guyana amid escalating tensions between the bordering South American countries. The company commits to remain involved, focusing on efficient and responsible resource development in line with the agreement with the Guyana government.

ExxonMobil is steadfast in its commitment to continue operations in Guyana despite Venezuela’s objections to the recent oil block auctions due to pending maritime delimitation. The company has bid for eight of the 14 blocks and awaits a response from the Guyanese government.

Earlier this month, Venezuela’s president, Nicolas Maduro, suggested that companies operating in the resource-rich Essequibo region in Guyana near significant oil deposits should cease operations within three months. Additionally, the Venezuela government aims to ban companies engaged in operations in Guyana from conducting business in the country.

ExxonMobil is currently achieving a daily oil production of 600,000 barrels by drilling more than 40 wells in Guyana’s Essequibo region. The ExxonMobil consortium has not only submitted a bid but has also obtained approval to develop three other areas in the region, which are believed to have additional oil deposits.

ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods predicts that the Venezuela-Guyana territorial dispute in the Essequibo region will not be resolved for a couple of years. He emphasizes the need for both nations to respect the arbitration outcome, noting global support from the United States, Europe and other Caribbean nations for the diplomatic resolution pursued by Guyana and Venezuela.

Zacks Rank & Stocks to Consider

ExxonMobil currently carries a Zack Rank #3 (Hold).

Investors interested in the energy sector might look at the following companies that presently carry a Zacks Rank #2 (Buy). You can see the complete list of today’s Zacks #1 Rank (Strong Buy) stocks here.

EOG Resources EOG boasts an appealing growth profile, delivers upper-quartile returns and is guided by a disciplined management team.

EOG Resources has a strong focus on returning capital to shareholders. From 1999 through 2024, the company is committed to raising its regular dividend at a compound annual growth rate of 21%. EOG has never suspended or lowered its dividend, even during business turmoil, reflecting a solid underlying business.

Matador Resources Company MTDR is among the leading oil and gas explorers in the shale and unconventional resources in the United States.

Matador has raised its fixed quarterly cash dividend by 33% to 20 cents per share (80 cents per share annually). This marks the fourth increment in the company’s fixed dividend since its introduction in the first quarter of 2021. The decision to once again increase the dividend underscores Matador's growing financial and operational strength.

Antero Midstream Corporation AM is a leading provider of integrated and customized midstream services.

Antero Midstream stands out in the industry with its impressive environmental record. With a mere 0.031% methane leak loss rate, it boasts one of the lowest rates in the industry. This demonstrates a strong commitment to minimizing its environmental impacts and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Additionally, an impressive 86% of wastewater received is either reused or recycled, showcasing their dedication to sustainable water management practices.

No comments:

Post a Comment