INSECT GENITALIA DOWN UNDER

Digitising decades of insect discoveries for future researchWe’re digitising the microscope slides at the Australian National Insect Collection to make them available for research all over the world.

BY ANDREA WILD

21 JANUARY 2024

Key points

Key points

There are more than 300,000 microscope slides in our collection, from tiny flies to moth genitalia.

We’re photographing our microscope slides and extracting the information recorded on them to increase their accessibility.

Later this year, we’ll be moving our microscope slides, and 12 million other specimens, to our new collections building in Canberra.

Our microscope slides preserve tiny insects and other tiny creatures like mites and nematodes (roundworms) for research under the microscope.

We’re now digitising the entire collection to make it available to the world.

What’s on our microscope slides of insects?

Our Australian National Insect Collection has 12 million specimens. They are mainly pinned insects. However, the collection also has more than 300,000 microscope slides that preserve around:80,000 aphids, coccids, whiteflies and thrips

70,000 tiny flies

75,000 mites and their relatives

50,000 nematodes

the genitalia of 36,000 moths… more on this later!

Nicole Fisher coordinates digitisation activities across our collections. She said the goal of digitising the microscope slides is to enable research.

"We want to help build a picture of things like species distributions and the ecology of insects that can spread diseases,” she said.

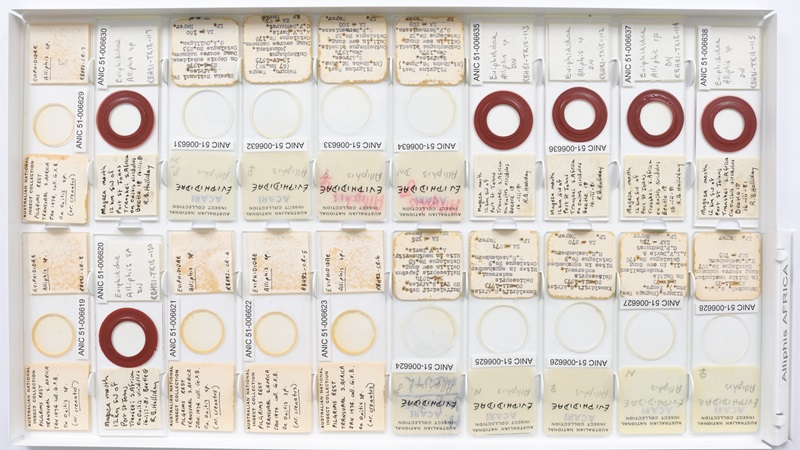

A tray of specimens preserved on microscope slides. Credit: Nicole Fisher

Take a picture!

The first step in digitising the microscope slides is to capture their metadata.

“We photograph each microscope slide and use optical character recognition to extract the handwritten or typed information, which includes when and where the specimen was collected,” Nicole said.

“There are many challenges because the writing on some is faded. Others are discoloured, some are etched and some have writing on the underside too.

“We need to give each microscope slide a unique number and repair damaged slides as we go. When the whole collection is digitised, we’ll have a searchable, digital database. We’ll know exactly how many microscope slides we have, what species they are and what information is recorded on them.”

Ryan Main imaging microscope slides at our Australia National Insect Collection. Credit: Nicole Fisher

Photographing our microscope slides of insects

Ryan Main is a photographer who previously worked with the team digitising the Australian National Herbarium.

“It only takes me a second to take a photo. But these microscope slides represent decades of work by the collectors,” Ryan said.

“When this project is finished, people all over the world will be able to see this collection.”

With so many microscope slides in the collection, Ryan sometimes photographs whole trays. The individual slides are then digitally separated. Despite this, it took Ryan and other staff more than six months just to work through the microscope slides of flies.

“The flies went on forever, just like the grasses seemed to when we digitised the plant specimens in the herbarium,” Ryan said.

Ryan needs to pause to clean dirty slides and repair broken slides, which requires considerable technical skill. Broken pieces need to be glued onto a new microscope slide with a glue that takes 24 hours to set.

Many of the microscope slides in the collection were prepared in the 1960s and 1970s. Some are up to 100 years old!

A big move for our collections

This year, the Australia National Insect Collection and the Australian National Wildlife Collection will be moving to a new facility at CSIRO in Canberra.

“As well as being digitised, the slide collection is going through an overhaul as it moves from old cabinets to new cabinets,” Nicole said.

“Early next year we’ll open both our new building and a fully digitised microscope slide collection. It’s a valuable resource that will be more readily available to researchers. The glass will be cleaner on the other side.”

We are cleaning and repairing older microscope slides before we digitise them.

Credit: Nicole Fisher

Not so secret bug’s business

If you’re wondering why we collect insect genitalia, we’re glad you asked!

For many species of insects, from moths to butterflies to weevils, genitalia are important way of telling species apart. This helps us describe species that are new to science.

This includes the Sapphire Azure Butterfly, a newly-described species endemic to Queensland that is threatened by land clearing.

The caterpillars of this butterfly feed on mistletoe and are cared for by the tree dwelling ant species Anonychomyrma inclinata. They depend on the ants for their survival.

The new National Collections Building is jointly funded by CSIRO and the Department of Education through the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy.

Not so secret bug’s business

If you’re wondering why we collect insect genitalia, we’re glad you asked!

For many species of insects, from moths to butterflies to weevils, genitalia are important way of telling species apart. This helps us describe species that are new to science.

This includes the Sapphire Azure Butterfly, a newly-described species endemic to Queensland that is threatened by land clearing.

The caterpillars of this butterfly feed on mistletoe and are cared for by the tree dwelling ant species Anonychomyrma inclinata. They depend on the ants for their survival.

The new National Collections Building is jointly funded by CSIRO and the Department of Education through the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy.

No comments:

Post a Comment