April 4, 2024

Source: Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies

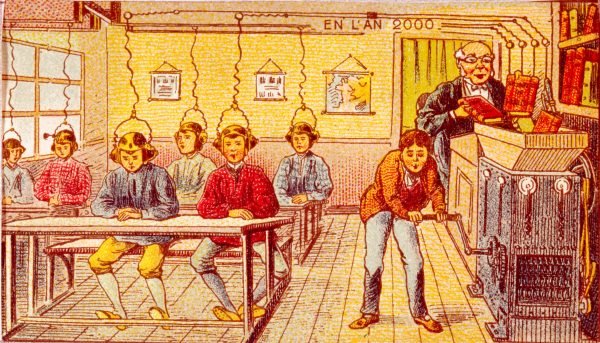

The “En L’An 2000,” or “Life in Year 2000” by Jean-Marc Côté depicts the futuristic culturization of humanity. (Françoise Foliot , Wikimédia France, Paris, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Source: Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies

The “En L’An 2000,” or “Life in Year 2000” by Jean-Marc Côté depicts the futuristic culturization of humanity. (Françoise Foliot , Wikimédia France, Paris, CC BY-SA 4.0)

LONG READ

Introduction

When I wrote “Cultural Studies, Public Pedagogy, and the Responsibility of Intellectuals, in 2004,” I wanted to stress the contribution that cultural studies made for educators in broadening their understanding of how politics and power worked through language, diverse symbolic processes, and a range of cultural apparatuses and institutions. My concern then was directed at the need for a new language among educators that would address how matters of agency and pedagogy were both related to power and were increasingly constructed and legitimated within several institutions ranging from universities to the rise of the social media and other cultural apparatuses. My aim was to broaden an understanding of how the dynamics of power and domination include not only economic forces but also those pedagogical practices that shape beliefs, desires, identities, and social relations that are central to forces of oppression and empowerment.

At the time, I wanted to point to new locations of struggles, new sites of politics, new forms of cultural production, and new spaces of resistance. Put simply, I wanted to make clear that cultural studies were redefining and interrogating culture as a new space for politics, resistance, and hope. In addition, I wanted to make critical pedagogy central to both cultural studies and to politics itself. Moreover, I argued that cultural studies offered a new understanding for the role that academics might play as public intellectuals in addressing a variety of audiences in the multiple spheres in which culture, power, and politics are produced, distributed, and normalized.

Central here is the development of a politics and pedagogy, if not a revitalized role for academics as public intellectuals. Such a view stresses the challenge with renewed vigor of not only keeping alive the habits of democracy, but of stressing that education should be the place where students realize themselves as critically informed and engaged citizens. Equally important is the recognition that education must be defended as a democratic public sphere, especially at a time when it is under massive assault by far-right extremists. My emphasis was on defining education through its claims on democracy and having academics acknowledge that there is no democracy without informed citizens. Under such circumstances, I stressed that educators as public intellectuals had to become border crossers by not limiting themselves to their disciplines or only speaking to other academics. Put simply, there was a need for them to speak to a variety of audiences in and out of the academy. Of major concern in my position was emphasizing how the merging of cultural studies and critical education clarified that matters of agency and subjectivity are the grounds of politics itself.

Today, culture has been weaponized unlike anything we have seen since the 1930s in Europe. The mobilizing passions of fascism are now being produced, circulated, and legitimated though all aspects of the mass media, which are increasingly under the control of a billionaire class. Cultural politics in the face of the growing fascist threat is more important to address than ever before, and the responsibility of academics to function as public intellectuals as urgent today as it ever was in the past. Politics is no longer a matter of simply voting or reforming institutions, it is also about changing consciousness so that individuals, students, and others can adopt a critical stance to take control over the forces that shape their lives and change the structures of domination that bear down on them. What I build up and stress in this article is that we are facing a political crisis in the narrow sense of the term — changing politics and economic structures – but also a cultural crisis, a crisis of the civic imagination. Hence, my article argues for changing both habits and minds connected to the capacity to not only understand the problems we currently face as educators and citizens but also how to intervene in the world in order to change it.

Cultural politics needs to function as an act of resistance and hope against the threat of a paralyzing indifference to the current threat of fascism. The ghosts of the past do not reside simply in the forgotten archives of history; they have turned into a living nightmare that that now shapes the present. Matters of culture and pedagogy are crucial sites where the struggle for a radical democracy needs to take place. Without that understanding, democracy in the current moment has little chance of surviving.

The long shadow of domestic fascism, defined as a project of racial and cultural cleansing, is with us once again both in North America and abroad. Educators have seen the ghosts of fascism before in acts of savage colonialism and dispossession, in an era of slavery marked by the brutality of whippings and neck irons, and in a Jim Crow age most obvious in the spectacularized horror of murderous lynchings. More recently we have viewed fascist acts of terror in a politics of disappearances and genocidal erasures under the dictatorships of Adolf Hitler, Augusto Pinochet in Chile, and others. Claims of genocide have also been made by an increasing number of international organizations and prominent public figures against the killing of civilians by both Israel and Hamas in the current war, but especially against Israel’s disproportionate killing of children in Gaza, now numbering over 5000 as of November 2023.Footnote1 And in each case, history has given us a glimpse of what the end of humanity would look like.Footnote2 Yet the lessons of history with its language of hate, machineries of torture, death camps and murderous violence as a political tool are too often ignored.

An upgraded form of fascism with its rabid nativism and hatred of racial mixing is currently at the center of politics in the United States. Traditional liberal values of equality, social justice, dissent, and freedom are now considered a threat to a Republican Party supportive of staggering levels of inequality, white Christian nationalism, and racial purity. Yet the lessons of history are too often ignored–though its mobilizing fascist passions are once again on the horizon.Footnote3 This politics of numbness and denial is not only true of the mainstream press but also applies to many liberal and left-oriented academics.Footnote4

America’s slide into a fascist politics demands a revitalized understanding of the historical moment in which we find ourselves, along with a systemic critical analysis of the new political formations that mark this period. This is especially true as neoliberalism can no longer defend itself. The destabilizing conditions of global capitalism with its mix of savage inequalities and expanding methods of control and repression point to both a legitimation crisis and a turn towards a revitalized and rebranded form of fascism. This neo-fascist resurgence is part of a counter-revolution waged against the student revolts of the sixties, the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, and a range of resistance insurgencies that have gained force over the last 60 years.Footnote5

The promise and ideals of democracy are receding as right-wing extremists breathe new life into a fascist past. This is particularly true, as education has increasingly become a tool of domination as right-wing pedagogical apparatuses controlled by the entrepreneurs of hate attack workers, the poor, people of color, trans people, immigrants from the south, and others considered disposable. Confronting this fascist counter-revolutionary movement necessitates creating a new language, rethinking education as a central element of politics, revitalizing the role of academics as public intellectuals. This impending threat also necessitates the building of a mass social movement to construct empowering terrains of education, politics, justice, culture, and power that challenge existing systems of white supremacy, white nationalism, manufactured ignorance, civic illiteracy, and economic oppression.

Introduction

When I wrote “Cultural Studies, Public Pedagogy, and the Responsibility of Intellectuals, in 2004,” I wanted to stress the contribution that cultural studies made for educators in broadening their understanding of how politics and power worked through language, diverse symbolic processes, and a range of cultural apparatuses and institutions. My concern then was directed at the need for a new language among educators that would address how matters of agency and pedagogy were both related to power and were increasingly constructed and legitimated within several institutions ranging from universities to the rise of the social media and other cultural apparatuses. My aim was to broaden an understanding of how the dynamics of power and domination include not only economic forces but also those pedagogical practices that shape beliefs, desires, identities, and social relations that are central to forces of oppression and empowerment.

At the time, I wanted to point to new locations of struggles, new sites of politics, new forms of cultural production, and new spaces of resistance. Put simply, I wanted to make clear that cultural studies were redefining and interrogating culture as a new space for politics, resistance, and hope. In addition, I wanted to make critical pedagogy central to both cultural studies and to politics itself. Moreover, I argued that cultural studies offered a new understanding for the role that academics might play as public intellectuals in addressing a variety of audiences in the multiple spheres in which culture, power, and politics are produced, distributed, and normalized.

Central here is the development of a politics and pedagogy, if not a revitalized role for academics as public intellectuals. Such a view stresses the challenge with renewed vigor of not only keeping alive the habits of democracy, but of stressing that education should be the place where students realize themselves as critically informed and engaged citizens. Equally important is the recognition that education must be defended as a democratic public sphere, especially at a time when it is under massive assault by far-right extremists. My emphasis was on defining education through its claims on democracy and having academics acknowledge that there is no democracy without informed citizens. Under such circumstances, I stressed that educators as public intellectuals had to become border crossers by not limiting themselves to their disciplines or only speaking to other academics. Put simply, there was a need for them to speak to a variety of audiences in and out of the academy. Of major concern in my position was emphasizing how the merging of cultural studies and critical education clarified that matters of agency and subjectivity are the grounds of politics itself.

Today, culture has been weaponized unlike anything we have seen since the 1930s in Europe. The mobilizing passions of fascism are now being produced, circulated, and legitimated though all aspects of the mass media, which are increasingly under the control of a billionaire class. Cultural politics in the face of the growing fascist threat is more important to address than ever before, and the responsibility of academics to function as public intellectuals as urgent today as it ever was in the past. Politics is no longer a matter of simply voting or reforming institutions, it is also about changing consciousness so that individuals, students, and others can adopt a critical stance to take control over the forces that shape their lives and change the structures of domination that bear down on them. What I build up and stress in this article is that we are facing a political crisis in the narrow sense of the term — changing politics and economic structures – but also a cultural crisis, a crisis of the civic imagination. Hence, my article argues for changing both habits and minds connected to the capacity to not only understand the problems we currently face as educators and citizens but also how to intervene in the world in order to change it.

Cultural politics needs to function as an act of resistance and hope against the threat of a paralyzing indifference to the current threat of fascism. The ghosts of the past do not reside simply in the forgotten archives of history; they have turned into a living nightmare that that now shapes the present. Matters of culture and pedagogy are crucial sites where the struggle for a radical democracy needs to take place. Without that understanding, democracy in the current moment has little chance of surviving.

The long shadow of domestic fascism, defined as a project of racial and cultural cleansing, is with us once again both in North America and abroad. Educators have seen the ghosts of fascism before in acts of savage colonialism and dispossession, in an era of slavery marked by the brutality of whippings and neck irons, and in a Jim Crow age most obvious in the spectacularized horror of murderous lynchings. More recently we have viewed fascist acts of terror in a politics of disappearances and genocidal erasures under the dictatorships of Adolf Hitler, Augusto Pinochet in Chile, and others. Claims of genocide have also been made by an increasing number of international organizations and prominent public figures against the killing of civilians by both Israel and Hamas in the current war, but especially against Israel’s disproportionate killing of children in Gaza, now numbering over 5000 as of November 2023.Footnote1 And in each case, history has given us a glimpse of what the end of humanity would look like.Footnote2 Yet the lessons of history with its language of hate, machineries of torture, death camps and murderous violence as a political tool are too often ignored.

An upgraded form of fascism with its rabid nativism and hatred of racial mixing is currently at the center of politics in the United States. Traditional liberal values of equality, social justice, dissent, and freedom are now considered a threat to a Republican Party supportive of staggering levels of inequality, white Christian nationalism, and racial purity. Yet the lessons of history are too often ignored–though its mobilizing fascist passions are once again on the horizon.Footnote3 This politics of numbness and denial is not only true of the mainstream press but also applies to many liberal and left-oriented academics.Footnote4

America’s slide into a fascist politics demands a revitalized understanding of the historical moment in which we find ourselves, along with a systemic critical analysis of the new political formations that mark this period. This is especially true as neoliberalism can no longer defend itself. The destabilizing conditions of global capitalism with its mix of savage inequalities and expanding methods of control and repression point to both a legitimation crisis and a turn towards a revitalized and rebranded form of fascism. This neo-fascist resurgence is part of a counter-revolution waged against the student revolts of the sixties, the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, and a range of resistance insurgencies that have gained force over the last 60 years.Footnote5

The promise and ideals of democracy are receding as right-wing extremists breathe new life into a fascist past. This is particularly true, as education has increasingly become a tool of domination as right-wing pedagogical apparatuses controlled by the entrepreneurs of hate attack workers, the poor, people of color, trans people, immigrants from the south, and others considered disposable. Confronting this fascist counter-revolutionary movement necessitates creating a new language, rethinking education as a central element of politics, revitalizing the role of academics as public intellectuals. This impending threat also necessitates the building of a mass social movement to construct empowering terrains of education, politics, justice, culture, and power that challenge existing systems of white supremacy, white nationalism, manufactured ignorance, civic illiteracy, and economic oppression.

Neoliberalism’s death march

We now live in a world that resembles a dystopian novel. This is a world marked by new crises and the intensification of old antagonisms. Since the late 1970s, a form of predatory capitalism or what can be called neoliberalism has waged war on the welfare state, public goods, and the social contract. Neoliberalism insists that the market should govern not just the economy, but also all aspects of society. It concentrates wealth in the hands of a financial elite and elevates unchecked self-interest, self-help, deregulation, and privatization as the governing principles of society. Under neoliberalism, everything is for sale, consumerism is the only obligation of citizenship, and the only relations that matter are modeled after forms of commercial exchange. At the same time, neoliberalism ignores basic human needs such as universal healthcare, food security, decent wages, and quality education. Moreover, it disparages human rights and imposes a culture of cruelty upon young people, people of color, women, immigrants, and those considered disposable.

Neoliberalism views government as the enemy of the market – except when it benefits wealthy corporations, limits society to the realm of the family and individuals, embraces a fixed hedonism, and challenges the very idea of the public good. Under neoliberalism, the political collapses into the personal and therapeutic, rendering all problems a singular matter of individual responsibility, thus making it almost impossible for individuals to translate private troubles into wider systemic considerations. This over emphasis on personal responsibility depoliticizes people by offering no language for addressing wider structural issues such as the call for better jobs, schools, safer neighborhoods, free education, and a basic universal wage, among other issues. It also stresses the language of emotional self-management, further producing a kind of ethical tranquilization and indifference to wider democratic struggles for racial, gender, and economic reforms. Moreover, under neoliberalism economic activity is divorced from social costs further eviscerating any sense of social responsibility at a time when policies that produce systemic racism, environmental destruction, militarism, and staggering inequality have become defining features of everyday life and established modes of governance. As Bernie Sanders notes, “It is not moral that three people on top own more wealth than the bottom half of American society, 165 million Americans … that’s not moral. That’s not right. That’s not what should exist in a democratic society.”Footnote6

Clearly, there is a need to raise fundamental questions about the role of education in a time of impending tyranny. Or, to put it another way, what are the obligations of education to democracy itself? That is, how can education work to reclaim a notion of democracy in which matters of social justice, freedom and equality become fundamental features of learning to live in a society.

The scourge of fascist education in the US

In the current historical moment, the threat of authoritarianism has become more dangerous than ever – one in which education has taken on a new role in the age of upgraded fascism. This authoritarian project is evident particularly in the United States as a number of far-right wing governors have put a range of reactionary educational policies in place that range from disallowing teachers to mention critical race theory and issues dealing with sexual orientation in their classrooms to forcing educators to sign loyalty oaths, post their syllabi online, give up tenure, and allow students to film their classes. Regarding the banning of books, Judd Legum notes,

Across the country, right-wing activists are seeking to ban thousands of books from schools and other public libraries. Those promoting the bans often claim they are acting to protect children from pornography. But the bans frequently target books ‘by and about people of color and LGBTQ individuals.’ Many of the books labeled as pornographic are highly acclaimed novels.Footnote7

The latter include Animal Farm, Maus, and The Color Purple. Such policies echo a fascist past in which the banning of books eventually led to both the imprisonment of dissidents and the eventual disappearance of bodies.

Not only are these attacks on certain books and ideas aimed at educators and minorities of class and color, this far-right attack on education is also part of a larger war on the very ability to think, question, and engage in politics from the vantage point of being critical, informed, and willing to engage in a culture of questioning. More generally, it is part of a concerted effort to destroy public and higher education and the very foundations of civic literacy and political agency. Under the rule of this emerging authoritarianism, political extremists are attempting to turn education into a space for killing the imagination, a place where provocative ideas are banished, and where faculty and students are punished through the threat of force or harsh disciplinary measures for speaking out, engaging in dissent, and holding power accountable.

In this case, the attempt to undermine public schooling and higher education as public goods and democratic public spheres is accompanied by a systemic attempt to destroy the notion that they are vital democratic public goods. Schools that view themselves as democratic public spheres are now disparaged by far-right Republican politicians and their allies as socialism factories, government schools, and citadels of left-wing thought.

In fact, as Jonathan Chait observes, what is being said by a right-wing Republican Party about American schools echoes a period in history in which fascist regimes used a similar language rooted in the cold war rhetoric of McCarthyism. For instance, Senator Marco Rubio of Florida has called schools “a cesspool of Marxist indoctrination.” Former secretary of State Mike Pompeo claims that “teachers’ unions, and the filth that they’re teaching our kids,” will “take this republic down.” Donald Trump has stated that “pink-haired communists [are] teaching our kids” and “Marxist maniacs and lunatics” run higher education. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis stated on Fox News that if he won the presidency in 2024, he “will … destroy leftism in this country and leave woke ideology in the dustbin of history.”Footnote8

This is more than anti-democratic, authoritarian rhetoric. It shapes poisonous policies in which education is increasingly defined as an animating space of repression, violence and weaponized as a tool of censorship, state indoctrination, and terminal exclusion. The examples have become too numerous to address. A short list would include a Florida school district banning a graphic novel version of Anne Frank’s Dairy,Footnote9 the firing of a Florida principal for showing her class an image of Michelangelo’s ‘David,’Footnote10 and the publishing of a textbook that removed any hint of racism from Rosa Park’s refusal to give up her bus seat in Montgomery, Alabama in 1955.Footnote11 There appears to be no limits on the part of right-wing activists in Florida to ban books. For instance, on July 12, 2023, an effort by right-wing extremists was made to ban the book Arthur’s Birthday, from libraries in the Clay County School District. The book by Marc Brown is “part of a popular children’s series that was spun off into an Emmy-winning children’s cartoon.”Footnote12 It gets worse.

In a number of states controlled by Republican governors, academic freedom is under assault as bills are passed with ban topics such as “Critical Race Theory, Critical Ethnic Studies, Radical Feminist Theory, Radical Gender Theory, Queer Theory, Critical Social Justice, or Intersectionality.”Footnote13 At Idaho’s public universities, faculty cannot talk about, teach, or write about abortion “may now face up to fourteen years of imprisonment.”Footnote14 There is more at work here than an attack on academic freedom, there is also an attempt to turn public universities into indoctrination centers modeled after the repressive modes of censorship endemic to past and present authoritarian regimes. All these actions are warning signs of a history about to be repeated.

At the current moment, it would be wise for educators to heed the words of Holocaust survivor and brilliant writer Primo Levi who argued in his book, In The Black Hole of Auschwitz, that “Every age has its own fascism.” In his book, The Voice of Memory, Levi elaborates on what he considered the elemental features of fascism. He wrote:

There is only one Truth, proclaimed from above; the newspapers are all alike, they all repeat the same one Truth. … As for books, only those that please the state are published and translated. You must seek any others on the outside and introduce them into your country at your own risk because they are considered more dangerous than drugs and explosives … Books not in favour … are burned in public bonfires in town squares … .In an authoritarian state it is considered permissible to alter the truth; to rewrite history retrospectively; to distort the news, suppress, the true, add the false. Propaganda is substituted for information.Footnote15

Making education central to politics

It is hard to imagine a more urgent moment for taking seriously Paulo Freire’s ongoing attempts to make education central to politics. At stake for Freire was the notion that education was a social concept, rooted in the goal of emancipation for all people. Moreover, his view of education encouraged human agency, one that was not content to enable people to only be critical thinkers, but also engaged individuals and social agents. Like John Dewey, Freire’s political project recognized that there is no democracy without knowledgeable and informed citizens. Today this insight is fundamental to creating the conditions to forge collective international resistance among educators, youth, artists, and other cultural workers in defense of public goods, if not democracy itself. Such a movement is important to resist and overcome the tyrannical fascist nightmares that have descended upon the United States, Italy, Hungary, India, and a number of other countries plagued by the rise of right-wing populist movements, far right militias such as the Proud Boys, and neo-Nazi parties.

The signposts of America’s turn toward a fascist notion of education are everywhere. Trans students are under attack, their history is being erased from school curricula, and the support of their care-givers is increasingly criminalized. African American history is sanitized and rewritten, while teachers, faculty, and librarians who contest or refuse this authoritarian script are being fired, demonized, and in some cases also subject to criminal charges. Mirroring an attack on trans people and the Institute for Sexual Science similar to the one that took place in the early years of the Third Reich, far right-wing politicians and white supremacists are waging a vicious war against trans youth and their teachers who are now treated as social pariahs while their supporters are slandered as pedophiles and groomers.

The growing threat of authoritarianism is also visible in the emergence of an anti-intellectual culture that derides any notion of critical education. What was once unthinkable regarding attacks on education has become normalized. Ignorance is now praised as a virtue and white supremacy and white Christian nationalism are now the organizing principles of governance and education in many American states and several countries globally.

This right-wing assault on democracy is a crisis that cannot be allowed to turn into a catastrophe in which all hope is lost. This suggests viewing education as a political concept, rooted in the goal of empowerment and emancipation for all people, especially if we do not want to default on education’s role as a democratic public sphere. Moreover, as I mentioned in my 2004 article, “Cultural Studies, Public Pedagogy, and the Responsibility of Intellectuals,” the issue of recognizing that culture is a site of active struggle and integrates institutionally and symbolic forms in making education central to politics is more important today than ever before. For too many theorists, culture has become merely a site of domination, used by the far right to weaponize language, images, and a range of information platforms. Not only does such a reading misread the emancipatory possibilities of culture, but it also denies the powerful role it can play as a radical educational force.

Culture as a site of struggle represents a pedagogical practice that calls students beyond themselves, embraces the ethical imperative for them to care for others, embrace historical memory, work to dismantle structures of domination, and to become subjects rather than objects of history, politics, and power. If educators as public intellectuals are going to develop a politics capable of awakening students’ critical, imaginative, and historical sensibilities, it is vital to engage education as a project of individual and collective empowerment – a project based on the search for truth, an enlarging of the civic imagination, and the practice of freedom.

It would be wise for educators to remember that the first casualty of authoritarianism are the minds that would oppose it. Fascism begins with the language of hate, and as Thom Hartmann observes

Before fascism can fully seize power in a nation, it must first be accepted by the people as a “patriotic” system of governance, representing the will of the majority of the nation. This is why fascists always scapegoat minorities first … before they acquire enough power to subjugate the entire nation itself.Footnote16

Against this warning, it is important for us as educators to note that the current era is one marked by the rise of disimagination machines that produce manufactured ignorance and concoct lies on an unprecedented level, giving authoritarianism a new life. As the historian Federico Finchelstein notes, it is crucial to recall that “one of the key lessons of the history of fascism is that racist lies led to extreme political violence.”Footnote17 We live at a time when the unthinkable has become normalized so that anything can be said and everything that matters unsaid. Moreover, this degrading of truth and the emptying of language makes it all the more difficult to distinguish good from evil, justice from injustice. Under such circumstances, the American public is rapidly losing a language and ethical grammar that challenges the political and racist machineries of cruelty, state violence and targeted exclusions.Footnote18

Education both in its symbolic and institutional forms has a vital role to play in fighting the resurgence of false renderings of history, white supremacy, religious fundamentalism, an accelerating militarism, and ultra-nationalism. As far-right movements across the globe disseminate toxic racist and ultra-nationalist images of the past, it is essential to reclaim education as a form of historical consciousness and moral witnessing. This is especially true at a time when historical and social amnesia have become a national pastime, further normalizing an authoritarian politics that thrives on ignorance, fear, the suppression of dissent, and hate. The merging of power, new digital technologies, and everyday life have not only altered time and space, but they have also expanded the reach of culture as an educational force. A culture of lies, cruelty, and hate, coupled with a fear of history and a 24/7 flow of information now wages a war on historical consciousness, attention spans, and the conditions necessary to think, contemplate, and arrive at sound judgments.Footnote19 This is evident in the use of the new social media by Trump and his allies to deny election results, saturate the culture with lies about everything from climate change to attacks on trans students and Black history.Footnote20

The cultural force of education in the twenty-first century

It is crucial for educators to learn that education and schooling are not the same and schooling must be viewed as a sphere distinctive from the educative forces at work in the larger culture.Footnote21 The point of course is that an array of cultural apparatuses extending from social media and streaming services to the rise of artificial intelligence and corporate controlled media platforms also constitutes vast educational machinery with enormous power and influence. What both schooling and the wider cultural sphere of education have in common is that they often work in tandem to shape and orchestrate dominant social relations, constitute prevailing notions of common sense, and open up conceptual horizons, modes of identification, and social relations through which consciousness and identities are shaped and legitimated.

In the current age of barbarism and the crushing of dissent, there is a need for educators to acknowledge how the wider culture and pedagogies of closure operate as educational and political forces in the service of fascist politics and other modes of tyranny. Under such circumstances, educators and others must question not only what individuals learn in society, but what they must unlearn, and what institutions provide the conditions for them to do so. Against those cultural apparatuses producing apartheid pedagogies of repression and conformity – rooted in censorship, racism, and the killing of the imagination – there is the need for critical institutions and pedagogical practices that value a culture of questioning, view critical agency as a fundamental condition of public life, and reject indoctrination in favor of the search for justice within educational spaces and institutions that function as democratic public spheres.

A critical consciousness matters

Any viable pedagogy of resistance needs to create the educational and pedagogical visions and tools to produce a radical shift in consciousness; it must be capable of recognizing both the scorched earth policies of neoliberalism and the twisted fascist ideologies that support it. This shift in consciousness cannot occur without pedagogical interventions that speak to people in ways in which they can recognize themselves, identify with the issues being addressed, and place the privatization of their troubles in a broader systemic context.

An education for empowerment that functions as the practice of freedom should provide a classroom environment that is intellectually rigorous and critical, while allowing students to give voice to their experiences, aspirations, and dreams. It should be a protective and courageous space where students are able to speak, write, and act from a position of agency and informed judgment. It should be a place where education does the bridging work of connecting schools to the wider society, connect the self to others, and address important social and political issues. It should also provide the conditions for students to learn how to make connections with an increased sense of social responsibility coupled with a sense of justice. Pedagogy for the practice of freedom is rooted in a broader project of a resurgent and insurrectional democracy– one that relentlessly questions the kinds of labor practices, and forms of knowledge that enacted in public and higher education.

If the evolving authoritarianism and rebranded fascism in the United States, Canada, Europe and elsewhere is to be defeated, there is a need to make critical education an organizing principle of politics and, in part, this can be done with a language that exposes and unravels falsehoods, systems of oppression, and corrupt relations of power while making clear that an alternative future is possible. Hannah Arendt was right in arguing that language is crucial in highlighting the often hidden “crystalized elements” that make authoritarianism likely.Footnote22 The language of critical pedagogy and literacy are powerful tools in the search for truth and the condemnation of falsehoods and injustices. Moreover, it is through language that the history of fascism can be remembered and be used to make clear that fascism does not reside solely in the past and that its traces are always dormant, even in the strongest democracies.

Against those politicians, pundits, and academics who falsely claim that fascism rests entirely in the past, it is crucial to recognize that fascism is always present in history and can crystallize in different forms. Or as the historian Jason Stanley observes, “Fascism [is] ‘a political method’ that can appear anytime, anywhere, if conditions are right.”Footnote23 The historical arc of fascism is not frozen in history; its attributes lurk in different forms in diverse societies, waiting to adapt to times favorable to its emergence. As Paul Gilroy has noted, the “horrors [of fascism] are always much closer to us than we like to imagine,” and our duty is not to look away but to make them visible.Footnote24 The refusal by an array of politicians, scholars, and the mainstream media to acknowledge the scale of the fascist threat bearing down on American society is more than an act of refusal, it is an act of complicity. What is noticeable is that the fascist threats emanating from Trump and his political allies have become so unabashedly overt that there has been a fury of articles in the mainstream press warning about the fascist threat Trump poses to American democracy.Footnote25 Unfortunately, almost none of them focus on the political, economic, and cultural conditions that support him or even made Trump possible as a threat to democracy.

Ignorance now rules America. Not the simple, if innocent ignorance that comes from an absence of knowledge, but a malicious manufactured ignorance forged in the arrogance of refusing to think hard and critically about an issue, and to engage language in the pursuit of justice. James Baldwin was certainly right in issuing the stern warning in No Name in the Street that “Ignorance, allied with power, is the most ferocious enemy justice can have.”Footnote26 For the ruling elite and modern Republican Party, thinking is viewed as an act of stupidity, and thoughtlessness is considered a virtue. Traces of critical thought increasingly appear at the margins of the culture, as ignorance becomes the primary organizing principle of American society and a number of other countries across the globe. A culture of lies and ignorance now serves as a tool of politics to prevent power from being held accountable.

Under such circumstances, there is a full-scale attack on thoughtful reasoning, empathy, collective resistance, and the compassionate imagination. In some ways, the dictatorship of ignorance resembles what John Berger once called “ethicide,” defined by Joshua Sperling as “The blunting of the senses; the hollowing out of language; the erasure of connection with the past, the dead, place, the land, the soil; possibly, too, the erasure even of certain emotions, whether pity, compassion, consoling, mourning or hoping.”Footnote27 Words such as love, trust, freedom, responsibility, and choice have been deformed by a market and authoritarian logic that narrows their meaning to either a commodity, a reductive notion of self-interest, or generates a language of bigotry and hatred.

Freedom in this context means removing oneself from any sense of social responsibility, making it easier to retreat into privatized orbits of self-indulgence and communities of hate. Such actions are legitimated through an appeal to what Elizabeth Anker has called ugly freedoms. That is, freedoms emptied of any substantive meaning and used by far-right politicians and corporate controlled media to legitimate a discourse of hate and bigotry while actively depoliticizing people by making them complicit with the forces that impose misery and suffering upon their lives.

Given the current crisis of politics, agency, history, and memory, educators need a new political and pedagogical language for addressing the changing contexts and issues facing a world where anti-democratic forces draw upon an unprecedented convergence of resources – financial, cultural, political, economic, scientific, military, and technological–to exercise powerful and diverse forms of control.

As a political and moral practice, critical pedagogy combines a language of critique and a vision of possibility in the fight to revive civic literacy, civic activism, and a notion of shared and engaged citizenship. Politics loses its emancipatory possibilities if it cannot present the educational conditions for enabling students and others to think against the grain, and realize themselves as informed, critical, and engaged individuals. There is no emancipatory politics without a pedagogy capable of awakening consciousness, challenging common sense, and creating modes of analysis in which people discover a moment of recognition that enables them to rethink the conditions that shape their lives.

Academics as public intellectuals

Against the emerging fascist politics, educators should assume the role of public intellectuals and border crossers within broader social contexts. For example, this might include finding ways, when possible, to share their ideas with the wider public by making use of new media technologies and a range of other cultural apparatuses, especially those outlets that are willing to address a range of social problems critically. Embracing their role as public intellectuals, educators can speak to more general audiences in a language that is clear, accessible, and rigorous. As educators organize to assert their role as citizen-educators in a democracy, they can forge new alliances and connections to develop social movements that include and expand beyond working simply with unions. For example, we see evidence of such actions among teachers and students organizing against gun violence and systemic racism and doing so by aligning with parents, unions, and others to fight the gun lobbies and politicians bought and sold by the violence industries. Moreover, we see faculty joining with students, social justice activists, and youth movements in fighting back against white supremacists, some liberals, and far right politicians such as Florida Governor Ron DeSantis who are restricting academic freedom, attacking critical race theory, erasing African American history, undermining tenure, and banning books in public colleges and universities. Moreover, a number of critical scholars of race and gender such as Robin D. G. Kelley, Cornel West, Angela Y. Davis, and others speak to multiple and diverse audiences in a variety of sites, amplifying their role as engaged public intellectuals.

Education operates as a crucial site of power in the modern world and critical pedagogy has a key role to play in both understanding and challenging how power, knowledge, and values are deployed, affirmed, and resisted within and outside of traditional discourses and cultural spheres. This suggests that one of the most serious challenges facing teachers, artists, journalists, writers, parents, and other cultural workers is the task of developing discourses and pedagogical practices that connect, as Freire once suggested, a critical reading of the word and the world.

There is no agency without hope

In taking up this project, educators as public intellectuals should create the conditions that enable young people to view cynicism as unconvincing and hope practical. We live in an era in which hope is wounded, but far from lost. The anti-public intellectuals and anti-democratic politicians now attacking public and higher education have betrayed Hope, but at the same time hope becomes central to a larger struggle for social justice and democracy itself. Hope in this instance is educational, removed from the fantasy of an idealism that is unaware of the constraints facing the struggle for a radical democratic society. Educated hope is not a call to overlook the difficult conditions that shape both schools and the larger social order, nor is it a blueprint removed from specific contexts and struggles. On the contrary, it is the precondition for imagining a future that does not replicate the nightmares of the present, for not making the present the future.

Educated hope provides the basis for dignifying the labor of teachers; it offers up critical knowledge linked to democratic social change, affirms shared responsibilities, and encourages teachers and students to recognize ambivalence and uncertainty as fundamental dimensions of learning. Without hope, even in the darkest times, there is no possibility for resistance, dissent, and struggle. Agency is the condition of struggle, and hope is the condition of agency. Hope expands the space of the possible and becomes a way of recognizing and naming the incomplete nature of the present. Such hope offers the possibility of thinking beyond the given. As the great writer and novelist Eduardo Galeano once argued, we live at a time when hope is wounded but not lost.

As Martin Luther King Jr, John Dewey, Paulo Freire, and Nelson Mandela argued there is no project of freedom and liberation without education and that changing attitudes and institutions are interrelated. Central to this insight is the notion advanced by Pierre Bourdieu that the most important forms of domination are not only economic but also intellectual and pedagogical and lie on the side of belief and persuasion. This suggests that academics bear a responsibility in acknowledging that the current fight against an emerging authoritarianism and white nationalism across the globe is not only a struggle over economic structures or the commanding heights of corporate power. It is also a struggle over visions, ideas, consciousness, and the power to shift the culture itself. It is also as Arendt points out a struggle against “a widespread fear of judging.”Footnote28 Without the ability to judge, it becomes impossible to recover words that have meaning, imagine a future that does not mimic the dark times in which we live, and create a language that changes how we think about ourselves and our relationship to others. Any struggle for a radical democratic order will not take place if lies cancel out reason, ignorance dismantles informed judgments, and truth succumbs to demagogic appeals to unchecked power. As Francisco Goya warned “the sleep of reason produces monsters.”Footnote29

Democracy begins to fail, and political life becomes impoverished in the absence of those vital public spheres such as public and higher education in which civic values, public scholarship, and social engagement allow for a more imaginative grasp of a future that takes seriously the demands of justice, equity, and civic courage. Without financially robust schools, critical forms of education, and knowledgeable and civically courageous teachers, young people are denied the habits of citizenship, critical modes of agency, and the grammar of ethical responsibility. Democracy should be a way of thinking about education, one that thrives on connecting pedagogy to the practice of freedom, social responsibility and the public good.Footnote30 I want to conclude by making some suggestions, however incomplete, regarding what we can do as educators to save public and higher education and connect them to the broader struggle over democracy itself.

Elements of reform

First, in the midst of the current assault on public and higher education, educators should reclaim and expand its democratic vocation and in doing so align itself with a vision that embraces its mission as a public good. Understanding education as fundamental to a democracy, raises a central question here is what the role of education is in a democracy and in what capacity as David Clark argues is “democracy … an education that nurtures our capacity for democracy, and for sharing power rather than enduring or deferring to authority.”Footnote31 Second, educators should also acknowledge and make good on the claim that there is no democracy without informed and knowledgeable citizens. At stake here is the need to create the institutional contexts for faculty to have control over the conditions of their labor, enjoy academic freedom, and provide students with an education that nurtures their capacity to be critical and engaged citizens. Moreover, in addition to gaining control over the conditions of their labor, educators have a responsibility to connect their work to both those issues that make a democracy possible –matters of justice, freedom, and equity – while working to educate a broader public about the work they do and how crucial it is to all individuals, not just their students.

Third, education should be free and funded through federal funds that guarantee a quality education for everyone. The larger issue here is that education cannot serve the public good in a society marked by staggering forms of inequality. Rather than build bombs, fund the defense industry, and inflate a death dealing military budget, we need massive investments in public and higher education–This is an investment in which youth are written into the future, rather than potentially eliminated from it.

Fourth, in a world driven by data, metrics, fragmented ways of thinking, and the replacement of knowledge by the overabundance of information, educators need to teach students to be border crossers, who can think dialectically, comparatively, and historically. With the rise of data sciences, neurosciences, AI technology, zoom, and other electronically produced platforms, technological rationality increasingly defines and undermines the humanities and liberal arts. Spaces where broad-based knowledge and a culture of questioning might flourish are under threat giving a new urgency to the struggle to protect and preserve the liberal arts and humanities as fundamental to what it means to be educate students as critical and engaged citizens. Educators should teach students to engage in multiple literacies extending from print and visual culture to digital culture. Students need to learn how to think intersectionally, comprehensively, and relationally while also being able to not only consume culture, but produce it; they should learn how to be both cultural critics and cultural producers. In a world marked by increasing forms of social atomization, it is important to provide comprehensive understandings of the self, others, and the larger world to create the conditions for merging differences, building formative communities, and expanding the boundaries of compassion and solidarity.

Fifth, educators must defend critical education as the search for truth, the practice of freedom, and pedagogy of disturbance. Such pedagogy should unsettle commonsense, inform, and expand the horizons of the imagination. Such a task suggests that critical pedagogy should shift not only the way people think but also encourage them to shape the world in which they find themselves for the better. As the practice of freedom, critical pedagogy arises from the conviction that educators and other cultural workers have a responsibility to unsettle power, trouble consensus, and challenge common sense. This is a view of pedagogy that should disturb, inspire, and energize a vast array of individuals and publics. Such pedagogical practices should enable students to interrogate common-sense understandings of the world, take risks in their thinking, however difficult, and be willing to take a stand for free inquiry in the pursuit of truth, multiple ways of knowing, mutual respect, and civic values in the pursuit of social justice. Students need to learn how to think dangerously, push at the frontiers of knowledge, and support the notion that the search for justice is never finished and that no society is ever just enough. These are not merely methodical considerations but also moral and political practices because they presuppose the creation of students who can imagine a future where justice, equality, freedom, and democracy matter and are attainable.

Sixth, educators need to argue for a notion of education that is viewed as inherently political – one that relentlessly questions the kinds of labor, practices, and forms of teaching, research, and modes of evaluation that are enacted in public and higher education. Education is political in that it is always related to relations of power, connected to the acquisition of agency, and is a place where students realize themselves as citizens. Moreover, there is no mode of education that stands outside of the relationship between power and knowledge, escapes defining what knowledge is of most worth, and is free from envisioning notions of the future. While such an education does not offer guarantees, it defines itself as a moral and political practice that is by necessity implicated in power relations because it produces versions and visions of civic life, how we construct representations of ourselves, others, our physical and social environment, and the future itself.

Seventh, in an age in which educators are being censored, fired, losing tenure, and in some cases subject to criminal penalties, it is crucial for them to fight to gain control over the conditions of their labor. Without power, faculty are reduced to casual labor, play no role in the governing process, and work under labor conditions comparable to how workers are treated at Amazon and Walmart. Educators need a new vision, language, and collective strategy to regain the power, rightful influence, control and security over their work conditions and their ability to make meaningful contributions to their students and larger society.

It is crucial to remember that there is no democracy without informed citizens and no justice without a language critical of injustice. The central question here is what the role of education in a democracy is and how we can teach students to govern rather than be governed. There is no hope without a democratically driven education system. The greatest threat to education in North America and around the globe is anti-democratic ideologies and market values that believe public schools and higher education are failing because they are public and should not operate in the interests of furthering the promise and possibility of democracy. If schools are failing it is because they are being defunded, privatized, and modeled after white nationalist indoctrination spheres, transformed into testing centers, and reduced to regressive training practices.

Finally, I want to suggest that in a society in which democracy is under siege, it is crucial for educators to assume the role of public intellectuals to connect their work to crucial social issues and to fight for education as a crucial public good, especially in the face of a rising fascism across the globe. Hope matters, suggesting that educators remember and assert that alternative futures are possible and that acting on these beliefs is a precondition for making social change possible. In closing I want to return to my 2004 article in Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies and cite a paragraph, which is more important and relevant today than when I first wrote it in 2004.

At a time when our civil liberties are being destroyed and public institutions and goods all over the globe are under assault by the forces of a rapacious global capitalism, there is a sense of concrete urgency that demands not only the most militant forms of political opposition on the part of academics, but new modes of resistance and collective struggle buttressed by rigorous intellectual work, social responsibility, and political courage. The time has come for intellectuals to distinguish caution from cowardice and recognize the ever-fashionable display of rhetorical cleverness as a form of “disguised decadence.” As Derrida reminds us, democracy “demands the most concrete urgency … because as a concept it makes visible the promise of democracy, that which is to come.”

At issue here is the courage to take on the challenge of what kind of world we want – what kind of future we want to build for our children? The great philosopher, Ernst Bloch, insisted that hope taps into our deepest experiences and that without it reason and justice cannot blossom. In The Fire Next Time, James Baldwin adds a call for compassion and social responsibility to this notion of hope, one that is indebted to those who will follow us. He writes: “Generations do not cease to be born, and we are responsible to them … . [T]he moment we break faith with one another, the sea engulfs us, and the light goes out.” Now more than ever educators must live up to the challenge of keeping fires of resistance burning with a feverish intensity. Only then will we be able to keep the lights on and the future open. In addition to that eloquent appeal, I would say that history is open, and it is time to think differently in order to act differently, especially if, as educators, we want to imagine and fight for alternative democratic futures and build new horizons of possibility.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Radhika Sainath, “The Free Speech Exception.” Boston Review (October 30, 2023). Online: https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/the-free-speech-exception/; Adam Tooze, Samuel Moyn, Amia Srinivasan, et al. “The principle of human dignity must apply to all people,” The Guardian (November 22, 2023). Online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/nov/22/the-principle-of-human-dignity-must-apply-to-all-people; Judith Butler, “The Compass of Mourning.” London Review of Books (October 19, 2023). Online: https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v45/n20/judith-butler/the-compass-of-mourning.

2 Alberto Toscano, “The Long Shadow of Racial Fascism,” Boston Review. (October 27, 2020). Online http://bostonreview.net/race-politics/alberto-toscano-long-shadow-racial-fascism.

3 Henry A. Giroux, Pedagogy of Resistance (London: Bloomsbury, 2022).

4 Anthony DiMaggio, “Fascism Denial American Style: Exceptionalism in the Ivory Tower,” Counterpunch (April 5, 2023). Online: https://www.counterpunch.org/2023/04/05/fascism-denial-american-style-exceptionalism-in-the-ivory-tower/.

5 Henry A. Giroux, Insurrections: Education in an Age of Counter-Revolutionary Politics (London: Bloomsbury, 2023).

6 Jon Queally, “When 3 Men Richer Than 165 Million People, Sanders Says Working Class Must ‘Come Together’,” CommonDreams (June 4, 2023). Online: https://www.commondreams.org/news/immoral-inequality-bernie-sanders.

7 Judd Legum, “Banning Book Bans,” Popular Information (May 31, 2023). Online: https://popular.info/p/banning-book-bans?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=1664&post_id=124913640&isFreemail=false&utm_medium=email.

8 Martin Pengelly, “Ron DeSantis says he will ‘destroy leftism’ in US if elected president,” The Guardian (May 30, 2023). Online: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/may/30/ron-desantis-fox-news-interview-destroy-leftism.

9 Gloria Oladipo, “Texas teacher fired for showing Anne Frank graphic novel to eighth-graders,” The Guardian (September 20, 2023). Online: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/sep/20/texas-teacher-fired-anne-frank-book-ban.

10 Richard Whiddington, “The Florida Principal Fired for Allowing a Lesson on Michelangelo’s ‘David’ Went to Italy to See the Sculpture Herself—and Was Rather Impressed,” ArtNews (April 28, 2023). Online: https://news.artnet.com/news/fired-florida-principal-visited-michelangelo-david-2292636#:~:text=Museums-,The%20Florida%20Principal%20Fired%20for%20Allowing%20a%20Lesson%20on%20Michelangelo’s,way%2C%22%20Hope%20Carrasquilla%20said.

11 Charisma Madarang, “Publisher Deletes Race From Rosa Parks Story for Florida,” Rolling Stone (March 16, 2023). Online: https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/race-deleted-rosa-parks-history-florida-textbooks-1234698582/.

12 Jedd Legum, “Right-wing activists seek to ban “Arthur’s Birthday” from Florida school libraries,” Popular Information (July 20, 2023). Online: https://popular.info/p/right-wing-activists-seek-to-ban.

13 Tom Mockaitis, “Attacks on academic freedom undermine the quality of US education,” The Hill (April 21, 2023). Online: https://thehill.com/opinion/education/3962012-attacks-on-academic-freedom-undermine-the-quality-of-us-education/.

14 Elizabeth Gyori, “Idaho Wants to Jail Professors for Teaching About Abortion,” ACLU (August 9, 2023). Online: https://www.aclu.org/news/reproductive-freedom/idaho-wants-to-jail-professors-for-teaching-about-abortion.

15 Primo Levi, “Primo Levi’s Heartbreaking, Heroic Answers to the Most Common Questions He Was Asked About ‘Survival in Auschwitz’,” The New Republic (February 17, 1986). Online: https://newrepublic.com/article/119959/interview-primo-levi-survival-auschwitz.

16 Thom Hartmann, “Trump Town Hall: Is CNN Normalizing Fascism Next Week?” The Hartmann Report (May 3, 2023). Online: https://hartmannreport.com/p/trump-town-hall-is-cnn-normalizing.

17 Federico Finchelstein, A Brief History of Fascist Lies (Oakland: University of California Press, 2020), 1.

18 Frank B. Wilderson III, “Introduction: Unspeakable Ethics,” in Red, White, & Black, (London, UK: Duke University Press, 2012), 1–32.

19 See especially, Jonathan Crary, Scorched Earth: Beyond The Digital Age To A Post-capitalist World. (London: Verso Books, 2022).

20 Robin D. G. Kelley, “The Long War on Black Studies,” The New York Review of Books (June 17, 2023). Online: https://www.nybooks.com/online/2023/06/17/the-long-war-on-black-studies/.

21 See, for example, Jane Mayer, “The Making of the Fox News White House,” The New Yorker (March 4, 2019). Online: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/03/11/the-making-of-the-fox-news-white-house.

22 Hannah Arendt, Origins of Totalitarianism (New York: Harcourt Trade Publishers, New Edition, 2001).

23 Cited in Ruth Ben-Ghiat, “What Is Fascism?” Lucid Substack (December 7, 2022). Online: https://lucid.substack.com/p/what-is-fascism.

24 Paul Gilroy, “The 2019 Holberg Lecture, by Laureate Paul Gilroy: Never Again: refusing race and salvaging the human,” Holbergprisen, (November 11, 2019). Online: https://holbergprisen.no/en/news/holberg-prize/2019-holberg-lecture-laureate-paul-gilroy.

25 See, Chauncey Devega, “Americans are sleepwalking into a Trump dictatorship,” Salon (December 5, 2023). Online: https://www.salon.com/2023/12/05/americans-are-sleepwalking-into-a-dictatorship/; even neo-conservatives are raising the alarm about Trump’s fascism, see, for instance, Robert Kagan, “ A Trump dictatorship is increasingly inevitable. We should stop pretending.,” The Washington Post (November 30, 2023). Online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/11/30/trump-dictator-2024-election-robert-kagan/.

26 Cited in Toni Morrison, ed. James Baldwin, Collected Essays: No Name in the Street (New York: Library of America, 1998), 437.

27 Joshua Sperling cited in Lisa Appignanesi, “Berger’s Ways of Being,” The New York Review of Books (May 9, 2019). Online: https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2019/05/09/john-berger-ways-of-being/?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=NYR%20Tintoretto%20Berger%20Mueller&utm_content=NYR%20Tintoretto%20Berger%20Mueller+CID_22999ee4b377a478a5ed6d4ef5021162&utm_source=Newsletter&utm_term=John%20Bergers%20Ways%20of%20Being.

28 Hannah Arendt, “Personal Responsibility Under Dictatorship,” in Jerome Kohn, ed., Responsibility and Judgement, (NY: Schocken Books, 2003). Online: https://grattoncourses.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/responsibility-under-a-dictatorship-arendt.pdf.

29 Mark Vallen, “Goya and the Sleep of Reason,” Art for Change (March 31, 2023). Online: Francisco Goya warned “the sleep of reason produces monsters”.

30 Henry A. Giroux, The Terror of the Unforeseen (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Review of Books, 2019).

31 David L. Clark, “What is Democracy?,” NFB Blog (March 27, 2023). Online: https://blog.nfb.ca/blog/2023/05/04/edu-higher-learning-what-is-democracy/.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.DONATE

Henry A. Giroux (born 1943) is an internationally renowned writer and cultural critic, Professor Henry Giroux has authored, or co-authored over 65 books, written several hundred scholarly articles, delivered more than 250 public lectures, been a regular contributor to print, television, and radio news media outlets, and is one of the most cited Canadian academics working in any area of Humanities research. In 2002, he was named as one of the top fifty educational thinkers of the modern period in Fifty Modern Thinkers on

No comments:

Post a Comment