It’s a forgotten moment in American beverage history.

Robert Hellyer's book explains how America's taste in tea shifted over time.

ON MAY 11, 1869, AMERICA’S first transcontinental freight train set out from California. On that momentous day, its cargo was a load of Japanese green tea. Today, only 15 percent of the tea drunk annually in the United States is green, and the vast majority of that is produced in countries like China and Vietnam. But in the last decades of the 19th century, America’s tea of choice was green, and Japan was the major supplier.

“It’s just so amazing how something like this can be so quickly forgotten,” says Robert Hellyer, a professor of history at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. “And this is the challenge of a historian: trying to figure out why. There’s no documents that tell us ‘This is why we really [liked] green tea.’”

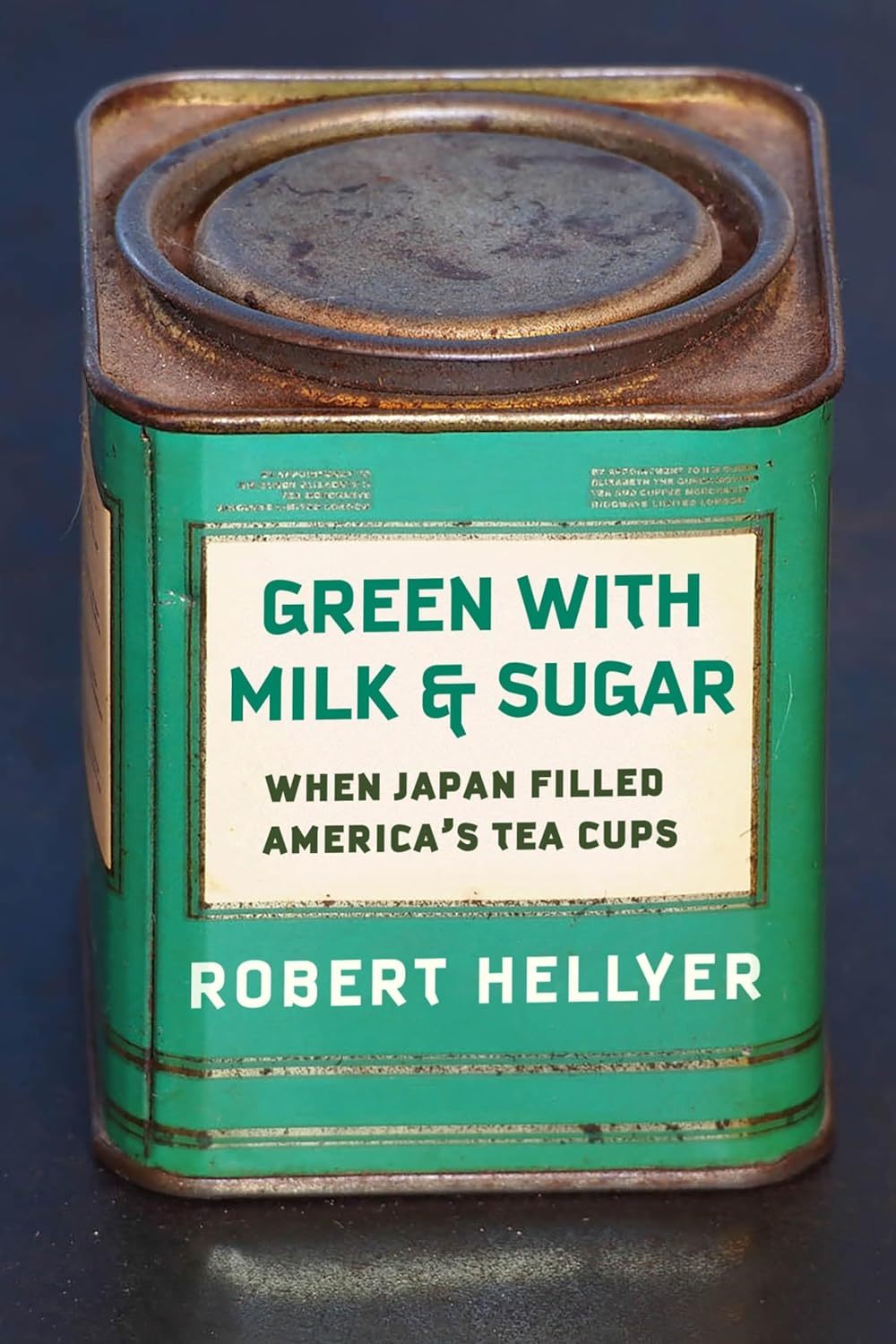

In his book Green with Milk and Sugar: When Japan Filled America’s Teacups, Hellyer sheds light on this little-known fact. “Green tea was the most popular tea in the U.S. since right after the Revolution, but there’s different theories about why,” he says. One theory is that the green tea that flooded the U.S. in the colonial era—grown in China and imported by the British East India Company—may have been “leftovers” after the best tea went to British consumers. “But Americans started to really like green tea, and see it as more sophisticated,” says Hellyer.

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, China held a global monopoly on the tea trade, and key information about tea cultivation and production was kept secret from outsiders. It wasn’t until 1843 that Europeans found out that green and black teas come from the same plant. In the 1840s, the British covertly smuggled tea plants out of China and into colonial India, where they would eventually establish a rival tea industry. But even before British-grown tea became a major commodity, Japan entered the global tea market in the 1860s.

Hellyer cites the Meiji Restoration as the most significant factor in Japan establishing a tea trade of their own. This modernizing revolution ended the last feudal regime in Japan and resulted in a major restructuring of power. “In the new regime, there are groups in Japan who see it as important to export tea to the West in a way that they’ve never explored before,” says Hellyer. Some of the individuals involved in this new booming trade were Japanese samurai who became tea farmers after the Meiji Restoration, and Hellyer’s own American ancestors who worked in the tea export business.

Japanese traders took advantage of direct sea routes to Seattle and San Francisco, and the United States became the biggest market for Japanese-grown tea. “By about 1880, [Japan] had about 40 percent of the U.S. market,” says Hellyer. The Midwest was known to consume the most green tea of any region. “In the Midwest, green tea really became popular from the 1870s and ‘80s,” says Hellyer. “That’s a moment where there’s such economic growth in the Midwest; where you have huge cities, notably Chicago, bursting from the prairie. And the people there are becoming wealthy, but as they develop new cultures, they are latching onto the established culture of tea to show their wealth.”

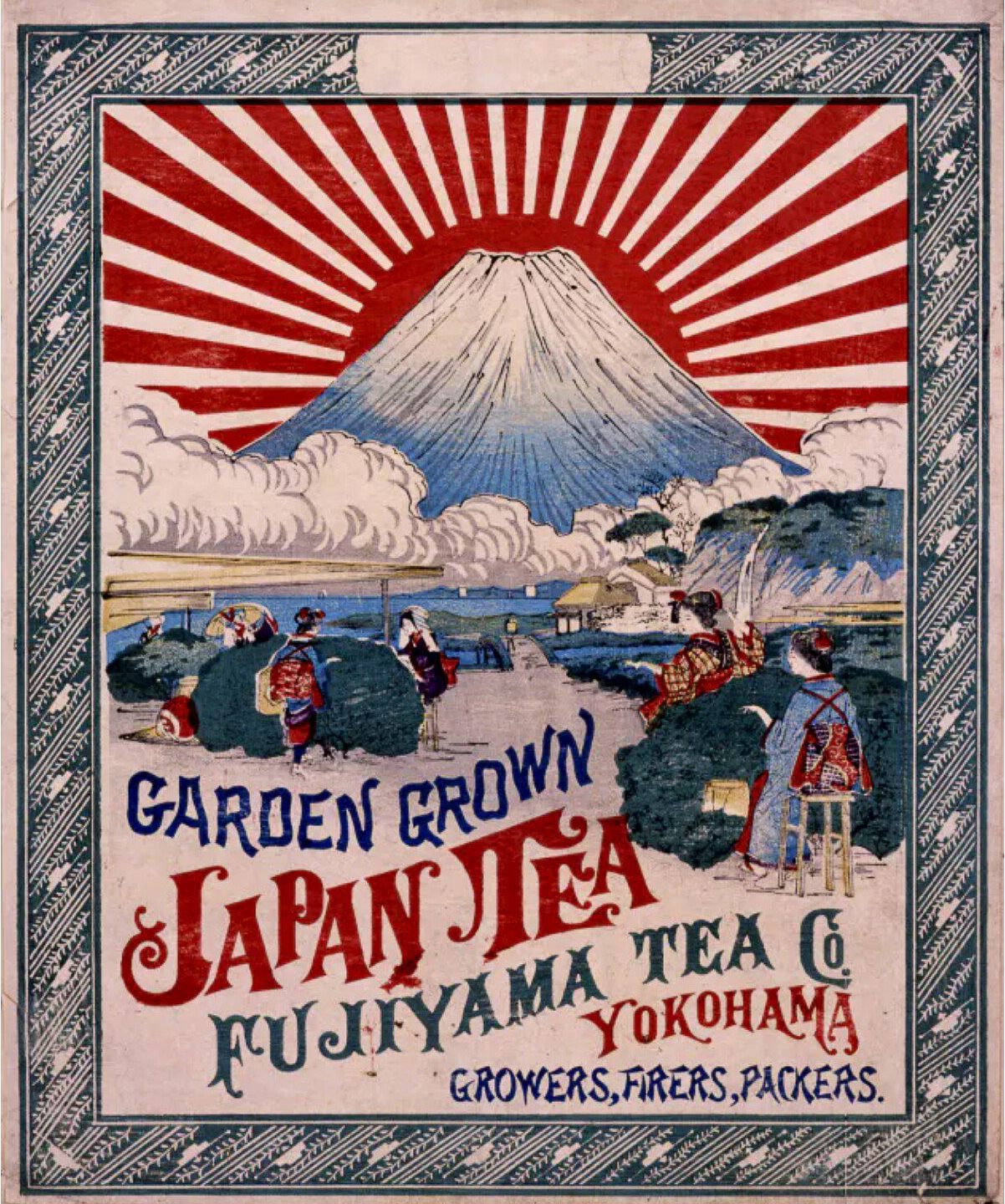

Japanese merchants promoted their product in the United States with elegantly-designed labels and advertisements that presented an image of Japan as refined, artistic, and nonthreatening. Yet by the 1920s, another major shift in America’s tea habits had occurred. Black tea grown in British India started to replace Japanese green as America’s preference. In his book, Hellyer notes that this was due to a combination of socioeconomic factors and increasing anti-Japanese sentiment. Marketing played an important role, as merchants seeking to oust non-British teas from the market used racist imagery in their advertisements, portraying both the Chinese and Japanese and their teas as inferior and unhygienic.

The shift in the American tea market changed Japan’s tea market as well. While Japanese tea drinkers have always preferred green over black, “in the past, it was a lower grade of green tea, called buncha” that was the most popular in Japan, Hellyer explains. Buncha was cheaper and had a more brownish color when brewed. With Americans losing interest in green tea, Japanese merchants with a newfound surplus of expensive tea started marketing it aggressively in their home country. This created an increased demand in Japan for the fine, high-grade green tea that is still popular today.

Throughout his book, Hellyer describes a time when green tea was seen “as an everyday, not exotic, product” in the United States. And what’s more American than colorful food and drinks? Merchants often enhanced their tea’s green color with toxic additives like graphite and Prussian blue, a synthetic pigment more commonly used in paint. Ironically, the chemical colorants that made green tea more desirable to consumers in the 19th century would come to be viewed negatively in the 1920s, when advertisers promoted black tea as unadulterated and pure.

Americans of the time “wanted what would look good at the store,” says Hellyer. “Isn’t the taste more important? Apparently not. It needed to look good. And you’re probably adding a lot of milk and sugar to it, so hey, it’s fine.”

Lettice Bryan's Tea Punch

Adapted from The Kentucky Housewife by Lettice Bryan (1839)

- Prep time: 5 minutes

- Cook time: 20 minutes

- Total time: 25 minutes

- 5 - 6 servings

Ingredients

- 3 cups strong green tea

- 2 1/2 cups sugar

- 1 cup cream

- 1 bottle of red wine or champagne

Instructions

- Brew the tea.

- While the tea is still hot, mix in the sugar so that it melts completely.

- Add the cream.

- Gradually add the wine or champagne, stirring carefully to prevent overflowing.

- Reheat to boiling and serve hot, or, chill and serve cold.

Notes and Tips

Alcoholic punch made with tea was “a pre-Civil War trend” in the United States, says Hellyer, particularly in the South. One such drink, known as “Fish House Punch” after the fishing club that served it, was a favorite of George Washington, who allegedly skipped three days of diary-writing while recovering from a night of punch-fueled revelry.

Such beverages were the earliest iced tea drinks, although some, like this 1839 recipe from The Kentucky Housewife by Lettice Bryan, could be served either hot or cold. Bryan didn’t specify what type of “strong tea” to use, but we can assume that she meant green. Other ingredients include cream, loaf sugar, and either champagne or claret, a 19th-century English term for red Bordeaux wine.

No comments:

Post a Comment