A Ukrainian Socialist Went to War. Here’s

What He Thinks About Peace.

Wednesday 25 February 2026,

Four years into Russia’s invasion, Taras Bilous — a socialist serving in the Ukrainian army — reflects on exhaustion, negotiations, and why a bad ceasefire could be a boon for the far right.

The situation on the ground

Sasha Talaver: You’ve been in the army for almost four years. What is your job now? How are you feeling?

Taras Bilous: I’m a drone operator who performs aerial reconnaissance. I’m currently on leave to recover from injury, so I have more free time now than I have these past three years. I am feeling well, thank you. I still have a piece of shrapnel in my liver, but overall, I have fully recovered. I am currently in Kyiv with my parents, and my leave is coming to an end.

Sasha Talaver: What’s the situation in Kyiv, after the Russian shelling of energy facilities?

Taras Bilous: It has finally started to warm up, so things are getting better. The worst is over; at least there won’t be such severe frosts. In general, it all depended on the area — in some places, the heating hasn’t been working since January. It was hardest for the poor, people with disabilities, and so on.

This was definitely the hardest winter for civilians thus far: luckily, the previous winters were mild. Still, for many people not belonging to vulnerable groups, it was easier than in autumn 2022, when Russia first started bombing Ukraine’s energy infrastructure. Back then, the lights went out, the water supply completely stopped working, and there was no internet or mobile communication, sometimes all day. Now, even when we don’t have electricity, the water supply often works, and communication is stable.

The Western left and Trump’s “peace” push

Sasha Talaver: You wrote a well-known letter to the Western left in February 2022 in which you criticised it for insisting that its main enemy is in its own countries, and for its lack of solidarity with the armed resistance to the Russian invasion. [1] How do you assess the situation now, after Donald Trump’s push for negotiations?

Taras Bilous: Circumstances have changed, and my position has changed somewhat accordingly. But what I wrote then was generally correct. I think that Trump’s failure in the peace negotiations confirms what I wrote then: "A call for diplomacy in itself means nothing if we don’t address negotiating positions, concrete concessions, and the willingness of the parties to adhere to any signed agreement." For example, regarding the ceasefire, Ukraine has favoured a complete and unconditional ceasefire since April 2025, but Russia still does not accept it. But who on the Left is saying that Russia must be forced to comply with the ceasefire?

The progress of peace negotiations

Sasha Talaver: How would you assess the progress of peace negotiations?

Taras Bilous: Only recently could we say that real negotiations are taking place. What happened over the past year was a show for Trump. He got involved without understanding the situation, with foolish illusions, and only made things worse.

When Trump won, I thought that things would most likely get worse for us, but to be honest, deep down I had a faint hope that a miracle might happen after all. Although Trump is the last person from whom I’d want to seek help, I, like other Ukrainians, above all want this damn war to be over. Unfortunately, it soon became clear that no good could be expected.

Importantly, Trump returned as president when both Ukraine and Russia were already exhausted by war, though certainly not as much as now. After the failure of the 2023 counteroffensive, the argument that "we cannot leave our people under occupation" became irrelevant. Throughout 2024, sentiment in favour of freezing the conflict gradually grew in Ukraine, including within the army. [2] Regardless of who won the US presidential election, negotiations would have started anyway. And it seems that the Ukrainian government understood this — the 2024 peace summit in Switzerland and the Kursk operation were, among other things, attempts to strengthen their position ahead of negotiations.

I think many Western analysts don’t understand that the main reason for Volodymyr Zelensky changing his position on the ceasefire was not pressure from Trump but a change in Ukrainians’ mood and recognition of battlefield realities. Zelensky shifted already back in November 2024, agreeing to the possibility of freezing the conflict without Russia returning all occupied territories. Everything pushed in this sense. Even since spring 2024, if I heard any mention in the army of Ukraine’s "1991 borders," it was always sarcastic.

Changing attitudes in the army

Sasha Talaver: Did opinions change in the army too?

Taras Bilous: Yeah, for sure. Maybe even earlier than in society as a whole. I first heard people talking about how it would be good to freeze the conflict back in autumn 2022, from guys who were fighting around Bakhmut and then got transferred to a rear unit. But back then this was a rare view, given the prevalent optimism after the successful Kharkiv operation. This gradually changed during 2024.

Sasha Talaver: How did people in your unit react to Trump’s initiatives?

Taras Bilous: At first, a mix: fears that Trump would cut off military aid and hopes that the war would finally end. But gradually, people stopped talking about it. When the twenty-eight points appeared last autumn, [3] some international journalists asked me what ordinary soldiers were saying, but I had no answer because it seemed that no one was paying attention anymore. In general, soldiers don’t often discuss such topics — usually, everyone is absorbed in their daily routine. For my team, the most pressing problem back then was mice in the blindage, not Trump.

Trump and the failure of negotiations

Sasha Talaver: But now, Ukraine was ready to freeze the conflict.

Taras Bilous: Yes, but to end the war, Trump had to increase pressure on Russia, and instead, we got a farce, with a red carpet for Vladimir Putin in Alaska. [4] Obviously, Trump doesn’t care about Ukraine and thought he could quickly achieve peace by forcing Ukraine to agree to Russia’s terms. Well, he didn’t understand either country, and if he really wanted to end the war quickly, his actions were counterproductive. Trump could write a book on "the art of how not to make a deal."

Trump surrendered one negotiating position after another, abandoned his demand for an unconditional ceasefire, and gave Putin what he wanted: recognition and a way out of international isolation. In essence, Putin played him for a fool for a whole year, and apparently only after his history lessons in Alaska did Trump begin to understand what he was dealing with. But now the Russians are rejecting all proposals, citing the “spirit of Anchorage.” Trump gave them that.

What real grounds are there to believe that Putin has abandoned his original plan to destroy the Ukrainian state? The Kremlin is still talking about the “root causes of the conflict.” The demand to surrender the unoccupied part of Donbas to Russia without a fight may be just a step towards this.

Sasha Talaver: But you said that real negotiations are finally underway. Why?

Taras Bilous: First, we have direct negotiations between Ukraine and Russia, rather than a show where the “great powers” agree on something without Ukraine’s involvement.

Second, the delegations’ membership has changed, and with it the nature of the negotiations. Regardless of the political conditions, important technical issues need to be resolved, in particular how to monitor the ceasefire. It would be better if, by the time political agreements finally become possible, decisions on such technical issues are already made. But on political issues, Russia is still putting forward conditions that are unacceptable to Ukraine, so this is at a standstill.

Thirdly, in October, Trump finally began to put pressure on Russia and imposed new sanctions against Russian oil companies. This is surely not enough, but it is something.

Moreover, last year, Russia’s economy finally faced serious problems and headed into stagnation. This is far from a collapse, but its problems are growing. Most of its reserve funds have already been spent in previous years on overcoming the consequences of sanctions and developing the military-industrial complex.

Security guarantees

Sasha Talaver: What do you think about one of the most pressing issues in the negotiations: security guarantees?

Taras Bilous: Let’s look at things soberly. In the context of the collapse of the international order, no written security guarantees are reliable. For Ukraine, there are two main security guarantees: the army and the fact that Russia has suffered heavy losses in this war. Now they will think twice before attacking us again.

As for the negotiations, let’s compare them with the Istanbul talks in spring 2022, where the Russians demanded that the Ukrainian army be limited to 85,000 troops. [5] Now they also want to limit our army, but no one is talking about such ridiculous numbers anymore. Back then, they wanted Russia to have the right to veto military aid to Ukraine in the event of aggression. This would have made the agreement no more valuable than the Budapest Memorandum from 1994. [6] Ukraine could never have agreed. We don’t know for certain all the conditions Russia is currently pushing, but it seems that they are no longer demanding such a veto.

Sasha Talaver: Some authors still say that Ukraine and Russia were close to signing a peace agreement in Istanbul, but Boris Johnson ruined such hopes.

Taras Bilous: I don’t understand how this can still be repeated after the publication of the draft security guarantee agreement and the article by Samuel Charap and Sergey Radchenko about these negotiations. [7] They show that even in this agreement, the parties’ positions on some key issues differed greatly. In addition, territorial issues were not even discussed then — they were put off until a personal meeting between Zelensky and Putin. Now the territories are being discussed, and this is the most difficult issue. Ultimately, according to Russian left-wing political scientist Ilya Matveev, [8] Charap and Radchenko overestimate Putin’s willingness to agree even to the terms discussed then.

As for Western countries, the main problem was that they refused to provide Ukraine with the security guarantees that Kyiv sought, for which reason it wanted to involve the US and others in negotiations. But even those countries that offered security guarantees were only promising to keep supplying weapons. Ukraine wanted more. As for those who write that Johnson disrupted the negotiations, if the West had actually agreed to provide the security guarantees that the Ukrainian government wanted, these same authors would have opposed it. Because that would have meant that in the event of new Russian aggression, the West would have to enter the war on Ukraine’s side.

The risks of freezing the conflict

Sasha Talaver: So, if I understand correctly, you believe that freezing the conflict would be the best possible option right now. But doesn’t that create significant risks?

Taras Bilous: Of course, it’s a risk. And it’s not just about the threat of a new war but also about the political, economic, and migration consequences of a frozen conflict. The more that Ukrainians see the likelihood of a new war, the more people will leave the country once this war ends. Incidentally, if it were indeed possible to deploy European troops in Ukraine, this would be important not only to prevent further Russian aggression but also simply to reassure people. Ukraine’s ability to repel future aggression also depends on how society perceives the outcome of this war. But every day we pay a very high price for continuing our resistance, and this creates other risks.

Even if Ukraine is given formal security guarantees, a new Russian invasion may still begin some time after the ceasefire, and the conditions would be much worse for us than they are now. It would end with the occupation of most of Ukraine. But if we continue the current war, there is a risk that eventually the front line will collapse, with the same bad outcome. I don’t think it’s a good idea to continue a war of attrition until we find out who has greater reserves of strength.

The situation on the front line is not so bad as to force us to agree to Russia’s terms, many of which are unacceptable because they would increase the risk of a new invasion. This is especially true of Russia’s demand to surrender the unoccupied part of Donbas without a fight. Still, we cannot afford to set maximalist goals either. We don’t have the luxury of seeing this as some theoretical question. Our lives depend on it.

Sasha Talaver: And what would you say to people who deny the risk of new Russian aggression?

Taras Bilous: If they’re so sure, they should publicly swear that they will personally come to fight against the Russian army in the event of a new invasion. Without this, their words are worthless.

Hope and the fall of Putin’s regime

Sasha Talaver: You paint a very bleak picture. Is there any hope for the future?

Taras Bilous: Even in the best-case scenario, Ukraine’s future looks pretty bleak. Whatever postwar reconstruction projects there may be, Ukraine will never fully recover from the losses this war has inflicted on us.

Ultimately, this applies not only to Ukraine. Even if Russia wins the war decisively, it cannot regain its previous international influence. Regardless of how much territory it manages to occupy, the war will have severe consequences for the Russian economy and broader society. Russia has paid for Putin’s imperial ambitions with its future.

Hope still lies in the fall of Putin’s regime. Perhaps the ceasefire will help. As far as I understand, the prevailing view among the Russian elite and society is that the full-scale invasion was a mistake by Putin, but since the war has already begun, it cannot risk defeat. After the war, the question "Why did we pay such a high price?" will become sharper still.

Essentially, only the Putin regime’s downfall can bring lasting peace. Until then, regardless of the terms Ukraine is forced to accept, any peace agreement will only freeze the conflict. Even if someone boasts that "I’ve brought you peace," Eastern Europe will still live in fear of new Russian aggression. And even if Ukraine is forced to capitulate, the result will not be peace but resistance to occupation by other means.

Ultimately, nothing lasts forever, and this regime will eventually fall anyhow. But apparently many Western authors and politicians who fear destabilisation in Russia after Putin’s downfall do not understand that the later this happens, the worse the consequences will be. I think this fear was one of the reasons for the Biden administration’s excessive caution, which led to the prolongation of the war and, accordingly, thousands of deaths, destroyed cities, and, in general, much more severe socioeconomic consequences.

Earlier chances for victory

Sasha Talaver: Do you think Ukraine had a better chance of winning earlier in the war?

Taras Bilous: Definitely. The chances were there until late autumn 2023. The losses and defeats Russia did suffer back then prompted Yevgeny Prigozhin’s rebellion. [9] If Russian losses had been even greater, it could have destabilised the regime further still. Unfortunately, this didn’t happen, partly due to mistakes by the Ukrainian Armed Forces command, but much more so due to the excessive caution of the Biden administration and the EU. They delayed the delivery of weapons too long, initially refusing to provide certain types of weapons, and when they finally did provide them, it was too late. Once it turned into a war of attrition, our chances diminished dramatically.

Elections and Zelensky’s future

Sasha Talaver: One of the Kremlin’s demands is for presidential elections in Ukraine. It seems that the Ukrainian authorities have recently changed their position on this. . .

Taras Bilous: It’s interesting, because Putin is demanding elections to get rid of Zelensky, whereas Zelensky instead wants elections in order to remain in power.

Sasha Talaver: Does he have a chance of winning?

Taras Bilous: His chances in an election during the war are definitely greater than they will be afterward. Right now, he has only one real competitor, the general Valeriy Zaluzhny. The war is holding back political battles, and people are self-censoring. Even now, talking to foreign journalists, I get the impression that they understand that Ukrainians self-censor when communicating with them, but these journalists don’t understand how much criticism of the authorities there is in Ukrainian media and on social networks. But after the war, this will become much more prevalent, and questions such as "Why did we suffer such heavy losses?" will arise sharply not only in Russia but also in Ukraine.

I would like Zelensky to leave politics after the war. But if he can renew his mandate until the end of the war, he will surely refuse to do so. It is difficult to predict what form public discontent will take then.

Moreover, all this looks bad not only from a political perspective but also from a legal one. According to the constitution, elections under martial law are prohibited, and changing the constitution during martial law is also not allowed. The bill on elections during martial law, which is currently being prepared by parliament, may be declared unconstitutional. Furthermore, Zelensky wants to hold a referendum at the same time as the elections, which is prohibited by law. The Central Election Commission has stated that it will take six months after the lifting of martial law just to organise the electoral process, but the government seems to be planning to carry out this process much faster. I don’t yet understand how they intend to do this.

Sasha Talaver: Why does he need a referendum?

Taras Bilous: To get approval for the peace deal and share the responsibility with society. A referendum would be necessary if Ukraine were forced to legally recognise Russia’s annexations. But neither Ukrainian society nor the government agrees to this. There’s no need for a referendum; it’s just another example of Zelensky’s unwillingness to make tough decisions. There have been many such examples during the war, and this has produced many problems. The government hoped that the war would end soon, so it postponed decisions on difficult issues until it was too late. Our military weakness is now primarily linked not to the cancellation of US military aid but to internal problems.

Trump’s impact on the war

Sasha Talaver: What impact did Trump’s policies have on the course of the war?

Taras Bilous: I am not a military analyst; as a soldier, I know about the situation on my section of the front, but I may not understand more general issues. But in general, I think Trump’s policies had the greatest impact not on the frontline situation but on Ukrainian rear cities. Our greatest military dependence on the US is in air defence. We cannot effectively defend rear cities from ballistic missiles without Patriot systems. Trump’s policies are one of the reasons for the sharp increase in civilian casualties last year. The current dire situation in our energy sector is also related to this.

As for the frontline situation, the effect was not as grave. Perhaps the greater impact was in 2024, when Republicans in Congress blocked new military aid for six months. Dependence on US military aid became significantly less, and Europe was able to partially compensate. HIMARS [10], for example, were very important in 2022, but now not so much. I don’t remember the last time I heard about Javelins. The battlefield has changed a lot because of drones.

Post-war Ukrainian politics

Sasha Talaver: Let’s move on to more civilian issues. What do you think Ukrainian politics will be like after the war?

Taras Bilous: Firstly, for Ukrainian politics to exist, Ukraine must remain intact. Secondly, I think the answer will depend heavily on the outcome of the war and the terms of the peace agreement. But surely politics will change significantly.

Traditional Ukrainian oligarchs have lost a lot because of the war. In addition to economic losses, many of them are under political pressure — five of the ten richest Ukrainian oligarchs are under Zelensky’s sanctions. Ihor Kolomoyskyi, who helped Zelensky win in 2019, has been in a detention centre since 2023. The influence of oligarch-controlled TV has significantly decreased. At the same time, a new military-industrial complex has emerged, and new political entrepreneurs will certainly emerge from it after the war.

The Ukrainian far right

Sasha Talaver: What about the Ukrainian far right?

Taras Bilous: Again, everything will depend on the war’s outcome. If it is seen as a defeat, the far right can insist, "We could have handled it better," and many people will believe them. Over the years, they have gained sufficient symbolic capital to do so. If the outcome is perceived as a victory (albeit not a complete one), it will be more difficult for them to convert their military successes into political capital. [11]

In general, far-right influence is likely to grow compared to prewar times; this is happening almost everywhere in the world. But I would not be 100 per cent sure of this. After Maidan, [12] it also seemed at first that we were in for a rise of the far right: Svoboda was one of the three main opposition parties and entered the new post-Maidan government, and the Right Sector was the most famous radical organisation on Maidan. But instead, Svoboda began to decline after Maidan, the Right Sector was unable to build on its success, and the Azov movement took years to build its structures and attract young people. In 2019, it seemed for a while that they had been given a new chance, but instead, the far right faced a new crisis.

There is also the "Trump factor" — some of the Ukrainian far right supported Trump until 2025 and are now being criticised for it. This can be compared to Canada, where Trump’s pressure undermined the Conservatives’ poll scores and instead aided the Liberals. But it’s hard to say how significant this influence will be in Ukraine.

The Ukrainian left

Sasha Talaver: What about the Ukrainian left?

Taras Bilous: The fact is, we are quite weak. As in other post-socialist countries, the anti-Stalinist left in Ukraine had to start from the ground up. [13] But while in Poland, Slovenia, Croatia, and other countries, the new left has had certain victories since 2014, in Ukraine, the annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas have split and weakened the Left.

The 2022 invasion had a different effect — there was a reactivation, and in 2023, the student union Priama Diia (Direct Action) [14] was even restored. But our activities are complicated by martial law and the fact that many experienced activists are serving in the army. Some have also died on the front lines, such as anarchist artist David Chichkan, anthropologist and author of the Commons journal Evheny Osievsky, and others. Russian anarchist Dmitry Petrov, who was our comrade and a Commons author, also died fighting on the Ukrainian side.

The Priama Diia student union’s activities have now become more difficult also due to far-right pressure. While early in the war the far right did not pay attention to us, conflicts began to arise again in 2024. But the conditions of the confrontation have now changed. For example, in 2024, the far right tried to disrupt the presentation of a student zine in Odesa, but anarchist veterans came to the students’ defence. Last year, the leader of Russian neo-Nazis in Ukraine, Denis Kapustin, staged a provocation at David Chichkan’s funeral, but he was pinned down by anarchist soldiers.

As for the future, again, everything depends heavily on the war’s outcome. It may sound counterintuitive, but if Ukraine loses, the far right will increase its influence, and in that case, we will most likely disappear as a collective. The next generation of leftists will be forced to start from scratch. Again.

Sasha Talaver: Some Western leftists still talk about the "old-left" heirs to the Soviet Communist Party in Ukraine, which were banned along with other pro-Russian parties in 2022. How do you answer questions about them?

Taras Bilous: I usually just show a video of a racist advertisement by Natalia Vitrenko, whose party was called the Progressive Socialist Party of Ukraine. Experience has shown that it is better to show something once than to try to explain everything in words.

European rearmament and blaming Ukraine

Sasha Talaver: There is currently a lot of discussion among the European left about increasing government spending on defence and militarisation. What do you think about this?

Taras Bilous: I am not an expert on European defence issues, and I have not had much time to figure out exactly where defence spending is going in Europe right now. We cooperate with the Left in the Nordic countries, and it seems to me that they have many good ideas on this topic. For example, they proposed a Europe-wide embargo on arms sales anywhere except Ukraine — in my opinion, this was a great idea. In general, international security is a topic for a separate long conversation. But I would like to comment on one thing: on social media, "some European leftists who oppose rearmament sometimes blame Ukraine" for this. But this is a blame-the-victim argument. The reason for the new arms race is not Ukrainian resistance but Russian invasion. If Ukraine loses, militarisation will only intensify.

Lessons from Trump’s first year

Sasha Talaver: Last question: What conclusion do you think the international left should draw from Trump’s first year in office?

Taras Bilous: There could be many conclusions. I’ll just say what concerns me most. Over the past year, the reactionary US president has done what the "antiwar" left has been calling for. What has this led to? Increased aggression, more civilian casualties, and more destruction. Things have only gotten worse. In this situation, I think the "antiwar" folks should have done some rethinking. But I still don’t see them doing that.

The logic of many “antiwar” leftists seems to be, “We provoked this war, so now let’s throw the victim of aggression under the bus.” In Trump’s version, it’s “Let’s throw the victims under the bus and rob them.” Despite the humanistic rhetoric, all proposals in practice boiled down to leaving Ukraine defenceless in the face of imperialist aggression. It should be obvious by now that this is the wrong approach. In the 1990s, the US forced Ukraine to give up its nuclear weapons to Russia, making us vulnerable. The US’s responsibility now is to help Ukraine, not to reward the aggressor.

24 February 2026

Footnotes

[1] Bilous’ open letter, published on 25 February 2022, became one of the most widely circulated statements by a Ukrainian socialist. See Taras Bilous, "A letter to the Western Left from Kyiv", Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières. Available at: http://europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article61279

[2] On the evolution of Ukrainian public opinion and the left’s assessment of the peace proposals, see Oleksandr Kyselov, "Fighting for the Least Unjust Peace for Ukraine", Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières. Available at: http://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article77459

[3] The leaked twenty-eight-point peace plan, drafted by Trump envoy Steve Witkoff and Russian official Kirill Dmitriev, was widely criticised as a capitulation. See Oleksandr Kyselov, "Ukraine Faces an Imperial Carve-Up", Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières. Available at: https://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article77242

[4] The Trump-Putin summit in Anchorage, Alaska became a reference point for the failure of US-brokered negotiations. Bilous argues that Trump’s concessions during this meeting undermined Ukraine’s negotiating position.

[5] The Istanbul negotiations of March–April 2022 are often cited as a near-miss for peace. Bilous challenges this interpretation, drawing on the analysis by Samuel Charap and Sergey Radchenko which showed significant gaps between the parties’ positions even at that stage.

[6] The Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances (1994) saw Ukraine surrender its nuclear arsenal — inherited from the Soviet Union — in exchange for security assurances from Russia, the United States and the United Kingdom. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and full-scale invasion in 2022 rendered these assurances meaningless.

[7] Charap and Radchenko published two analyses of the Istanbul talks in Foreign Affairs: "The Talks That Could Have Ended the War in Ukraine" (April 2024), based on examination of draft agreements and interviews with participants, and "Why Peace Talks Fail in Ukraine" (May 2025), drawing lessons for current negotiations. Both are available via the RAND Corporation at https://www.rand.org/pubs/external_publications/EP70437.html and https://www.rand.org/pubs/external_publications/EP70929.html

[8] Ilya Matveev is a Russian socialist, political economist and member of the Public Sociology Laboratory research group. Several of his analyses of Russian imperialism and domestic politics are available on ESSF. See Ilya Matveev, "Political imperialism, Putin’s Russia, and the need for a global left alternative", Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières. Available at: http://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article72148. See also Ilya Matveev, "Russia-Ukraine: Who Won and Who Lost?", Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières. Available at: http://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article72613

[9] Yevgeny Prigozhin, head of the Wagner private military company, led a brief armed mutiny against the Russian military command in June 2023. He was killed in a plane crash two months later.

[10] HIMARS (M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket System) is a US-manufactured multiple rocket launcher that became a symbol of Western military support for Ukraine, particularly in 2022 when it enabled Ukrainian forces to strike Russian logistics and command posts behind the front lines.

[11] For Bilous’ earlier assessment of the Ukrainian far right, see Taras Bilous and Stephen R. Shalom, "L’extrême droite en Ukraine", Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières. Available at: https://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article65654

[12] The Euromaidan protests (November 2013 – February 2014) were a wave of mass demonstrations in Ukraine, initially triggered by President Viktor Yanukovych’s decision to suspend an association agreement with the European Union. The protests culminated in Yanukovych’s ouster and the formation of a new government.

[13] On the challenges facing the Ukrainian left and the work of Sotsialnyi Rukh (Social Movement), see "Don’t exaggerate the influence of Russian propaganda" (interview with Taras Bilous), Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières. Available at: https://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article63762

[14] Priama Diia (Direct Action) is a Ukrainian anarcho-syndicalist student union, originally active in the 2000s and early 2010s, which was re-established in 2023 during the full-scale war.

Peace in Ukraine: the next steps

Just returned from a vital aid mission, Mick Antoniw MS reports on the mood among Ukrainians four years on from Russia’s full-scale invasion and sets out what needs to happen now.

FEBRUARY 23, 2026

Four years ago, I was in Ukraine just before the invasion. I have just returned from Kyiv, Pavlohrad and Dnipro as part of the Welsh Parliament Cross-Party Group Senedd4Ukraine, where I met with soldiers fighting on the front line and the Ukrainian Mineworkers trade unions.

Our team of 13 included Welsh Parliament politicians, former miners and trade union officials, as well as two Americans ashamed of Trump’s collaboration – a truly international team.

We delivered another six vehicles and vital medical supplies and equipment for front line units.

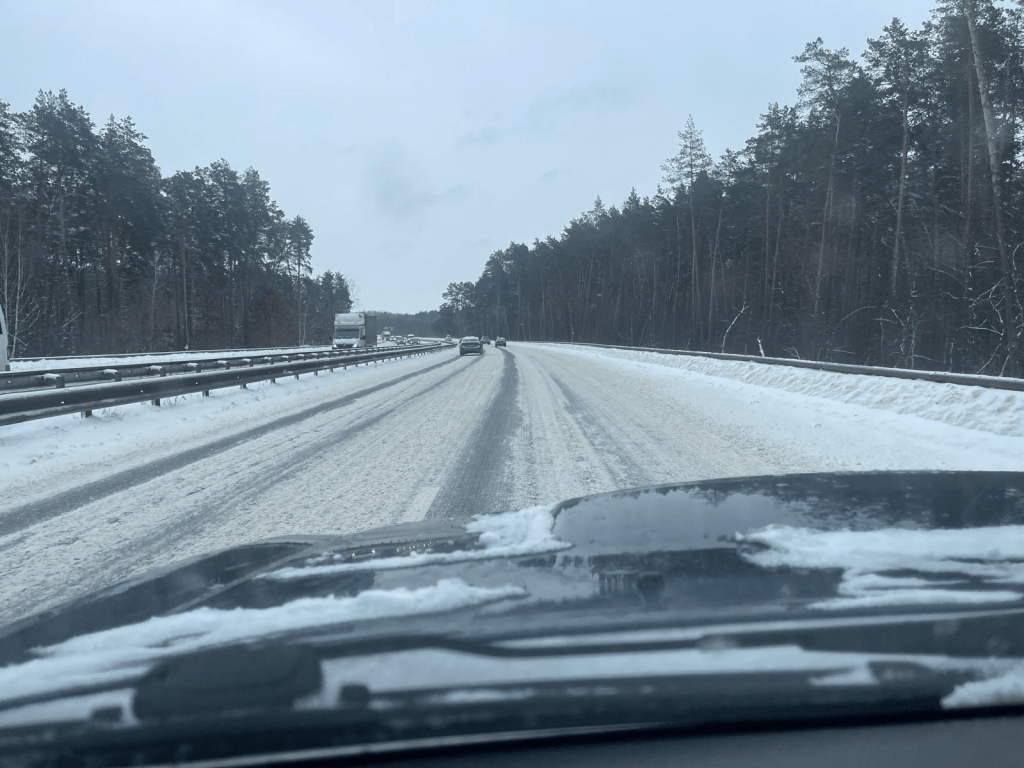

Weather conditions were treacherous. We faced snow, black ice and freezing conditions on the road to Kyiv and treacherous driving 500 miles to Pavlohrad and then Dnipro. It was a round trip of over 2,000 miles.

In Kyiv, we met with the Independent miners’ union and serving members direct from the Kharkiv and Sumy front lines. They came and went, urgent to get back to their comrades. In Pavlohrad, some of the vehicles were already on the way to Pokrovsk where Ukrainian forces are bit by bit pushing back the overstretched and exhausted Russians. Last month, Russia lost an estimated 35,000 killed or wounded.

The mood in Pavlohrad is sombre, angry and resilient. Earlier this month, Russia bombed a bus of miners returning from shift. Nine members were killed and more wounded. Survivors were then hunted by further drones.

The funerals have taken place and there are memorials in their memory. The trade union is ensuring the families are supported and looked after.

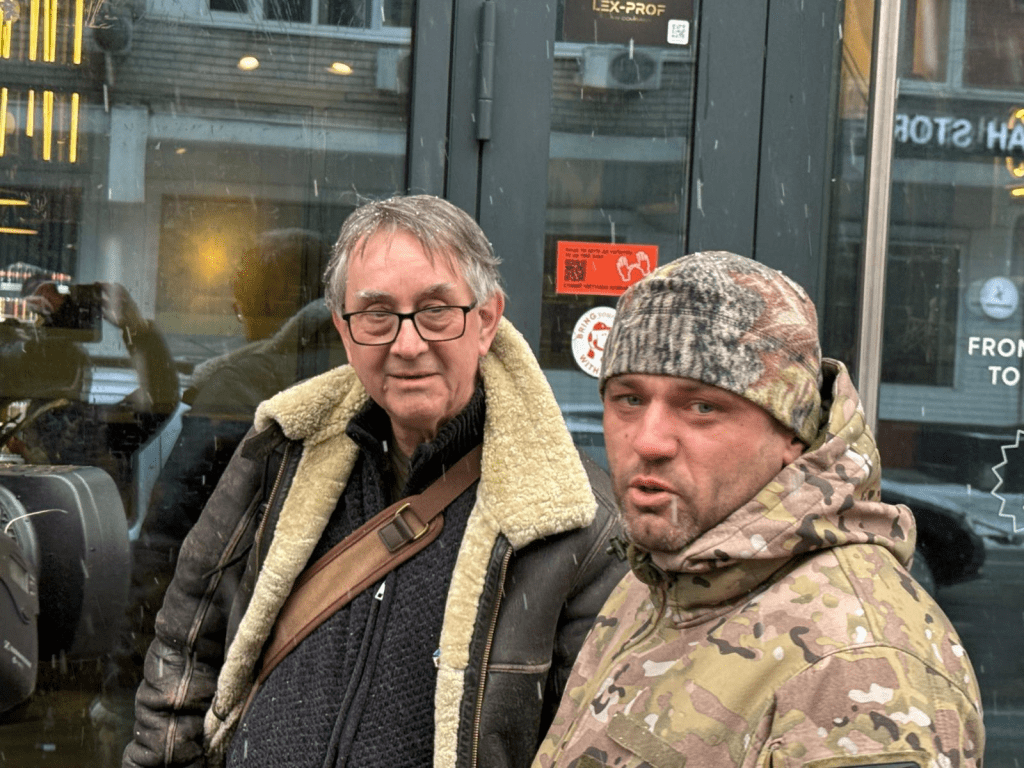

On to Dnipro, where we met with Shaun Pinner a former British soldier who is married to a Ukrainian and joined the Ukrainian army, fought at Mariupol and was subsequently captured, tortured and whose book Live, Fight, Survive describes the brutality of capture under the Russian fascists. Sentenced to death, he was subsequently part of an exchange for Ukrainian traitor Medvedchuk who had been captured by Ukraine as he tried to flee the country.

Our sixth and fifty-fifth vehicle to date went to my cousin’s unit fighting on the Zaporizhzhia front.

So, what is the current situation in Ukraine? It is freezing cold. Attacks on civilian buildings and energy infrastructure are having a disastrous impact on living conditions; yet all around public services are back up and running. The metro is operating. Substitute warm areas and food are provided. Energy is gradually being restored and importantly spring is on the way. The bars and restaurants are still mainly open. Everywhere there is the hum of generators.

Everyone I spoke to was resolute. Russia cannot win. They are losing, their economy is failing. Ukraine is now hitting back with devastating effect on its oil and gas production. Recently they destroyed various air defences deep into the Russian Federation, and missile production factories.

But it is very hard. Everyone wants peace but they do not believe Putin wants peace, not unless he is forced into it. Politically he is clamping down still further on dissent and social media. Russia is truly a fascist state now. Yet dissent is growing in the Russian Federation, those ethnic non-Russian countries still controlled by Moscow which are increasingly dissatisfied with the ruination of social facilities, the lack of investment in public services and the death toll which disproportionately is impacting on the ethnic minorities. Prices and inflation are rising. Food and basic products are increasingly expensive and even not available.

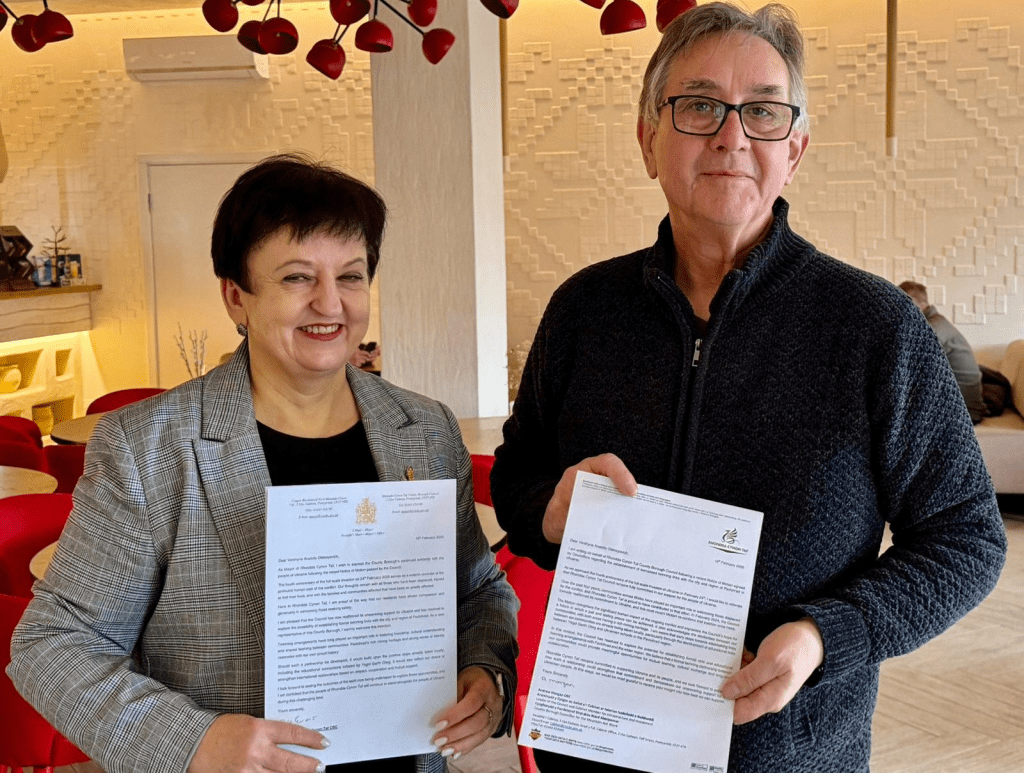

In Pavlohrad I handed letters to the Deputy Mayor from Rhondda Cynon Taf Council to explore twinning – one former mining area with another. This solidarity is truly amazing as were the beautiful paintings from school children who were asked to paint images of how they see a future Ukraine. Optimism and belief ooze through their paintings.

So what are the lessons and conclusions on these latest meetings, discussions and conversations?

There is no faith in the USA. But people do believe that Ukraine is part of Europe and must join the EU. There will be no peace without genuine security for Ukraine. Everyone believes that a peace on any other terms will be only temporary and unacceptable. Ukraine will not hand over unoccupied land. Russian is now being forced back, an example of its deeper weakness. It is losing more men than it can recruit amidst a growing economic deterioration.

Ukraine is still not getting the weapons it needs for air defence but the UK is recognised as probably its most resolute supporter, alongside France and Germany.

Trump’s connivance with Putin is perpetuating the war. Putin is maximising his reliance on Trump’s Presidency prior to the mid-term elections.

Trump is seen as an ally of Putin alongside other far right and proto-fascist leaders of Hungary and Slovakia, Orban and Fico.

They have threatened to cut off electricity to Ukraine unless they are allowed to import Russian oil and gas. Their recent meetings with Russia and the US have consolidated their connivance with Putin.

But geopolitics continue to change. Orban is soon likely to be gone and Trump neutered by the mid-term US elections.

Either way there is no likelihood Ukraine will concede their red lines: no hand over of non-occupied territory, no recognition of Russian sovereignty of Crimea or any occupied area.

The tide is turning. The pressure is now on Putin. Trump has lost his leverage and it is up to Europe to take the lead in diplomacy, but also in sanctions. The events at the Winter Olympics, allowing Russian athletes to participate and to allow Russian flags to fly at the Paralympics, illustrate the corruption at the heart of international sport. Ukrainians want the world to boycott Russia. Just as we campaigned for this against apartheid South Africa, so must we against Putin. Countries that commit war crimes and breach international law should not be afforded the respectability and comfort of International sport and culture. The pressure on Russia now needs to be escalated.

Europe must now step up and exploit Putin’s weakness. Defending Ukrainian skies, to protect the civilian population is now essential. We have the capacity to shoot down missiles and drones. We have the legal right under international law and the Budapest agreement to do so.

All we are missing is the strength or willpower and recognition that this could be the most important step to bringing the war to an end. Putin cannot win on the battlefield so he hopes to win by attacking the civilian population and using terrorism. He must not be allowed to succeed. Press on with the war crimes tribunals and press on demanding the use of Russian frozen assets for the defence and reconstruction of Ukraine.

We are relearning the lessons of Munich 1938. You cannot appease fascism. I still have the belief that Putin and his collaborators will one day face a war crimes tribunal.

Mick Antoniw MS is the Labour Senedd Member for Pontypridd and a founding member of Ukraine Solidarity.

Statement by UK trade unions in solidarity with Ukraine, on the fourth anniversary of the full-scale invasion

The statement below has been issued by UK trade unions, in association with the Ukraine Solidarity Campaign, on 23rd February 2026, for the fourth anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24th February. All the signatories are General Secretaries signing on behalf of their unions, all of which have policy in support of Ukraine made by their members through their democratic structures. In addition to support from the Trades Union Congress (TUC), the nine unions supporting the statement represent a clear majority of organised workers in the UK.

On the fourth anniversary of Russia’s full‑scale invasion of Ukraine, UK trade unions reaffirm our solidarity with Ukraine, its workers and their unions. Ukraine’s workers are not only defending their country but are standing up for democratic rights, freedoms and labour standards that underpin our movement. We send our greetings to our sister organisations, the FPU and KVPU, and commit our continuing support for them.

As Putin’s war of aggression enters its fifth year, Ukraine’s workers continue to face unrelenting violence. Systematic attacks on the energy system have plunged towns and cities into darkness, shutting schools and hospitals and placing entire communities at risk. Energy workers are restoring power under fire, often at immense personal danger, to keep people safe through severe winter conditions.

Russia’s deliberate targeting of civilians and infrastructure is a grave breach of international law and is deepening Ukraine’s humanitarian crisis as temperatures fall well below freezing.

Working people always bear the heaviest cost of war. On 1st February, fifteen miners were killed when a Russian drone struck their bus in the Pavlohrad district. In territories under Russia’s illegal occupation, reports expose forced labour, the suppression of trade union freedoms and the violent mistreatment of workers, alongside the wider killing and torture of civilians.

Tens of thousands of children have been abducted by Russia and subjected to abuse on an industrial scale. As always, women, oppressed minorities and children also bear the brunt of war.

We stand with Ukrainian unions in their call for the restoration of labour rights and for a socially just reconstruction that embeds collective bargaining and rejects deregulation and privatisation.

We also stand with Ukrainian and other refugees in the UK and insist that their rights and safety are upheld.

The UK trade union movement has a proud history of standing in solidarity with victims of fascism and imperialist aggression.

A victory for Putin’s regime would embolden authoritarian and far-right forces globally.

We therefore reaffirm our support for the Ukrainian people’s right to determine their own future, call for the immediate withdrawal of Russian forces from all occupied territories, and support Ukrainian trade unions’ appeals for the UK to provide the aid necessary to help secure a just and lasting peace.

Paul Nowak, General Secretary, Trades Union Congress; Andrea Egan, General Secretary, UNISON; Sharon Graham, General Secretary, Unite; Gary Smith, General Secretary, GMB; Daniel Kebede, General Secretary, NEU; Joanne Thomas, General Secretary, USDAW; Fran Heathcote, General Secretary, PCS; Jo Grady, General Secretary, UCU; Dave Calfe, General Secretary, ASLEF; Chris Kitchen, General Secretary, NUM.

The War in Ukraine at Four

It is old hat for those who know a bit about peace that it cannot be created by looking only at the various types of violence employed. The world’s focus on the Ukrainian battlefield and its characteristic mixing up ceasefire with peace is misplaced.

One has to ask: And why did they take to violence in the first place, particularly when other options and tools were ready to be employed? And could have stopped the violence and helped the parties find some kind of peaceful existence.

Further, what is it that makes it necessary for almost everybody to take sides with the parties but not address the underlying

How do we think about a doctor who just gives us a painkiller without doing a diagnosis that tells where the pain comes from and also has no Prognosis or Treatment?

At a deeper level, the tragic fourth anniversary of the war in Ukraine should be accompanied by an acknowledgement that the conflict is between NATO and Russia and has gone back to when NATO set up its first office in Kiev a couple of months after Ukraine became independent. It is about the conflict-accelerating expansion of NATO that broke all the well-documented promises Western leaders gave Gorbachev to the effect that NATO would not expand “one inch” – but later took in scores of countries around Russia.

And it is about the US-orchestrated and financed regime change under the Obama administration that took place – the Maidan Revolution/Uproar — that is 12 years ago these very days, February 18-23, 2014.

NATO is a military alliance; its expansion was politics by armament and spreading arms. Russia – after long and clear diplomatic warnings – decided to use weapons. Ukraine had built its army full of weapons (with the help of NATO countries, the US and its CIA, in particular) and killed thousands of Russians and took other Russophobic political initiatives — all backed up by the Army that then President Poroshenko later told the world that he considered “as my child.”

NATO answered with weapons. The EU answered with weapons. The US answered with weapons. The EU/NATO world plans to increase weapons to 5% of its GNP — unheard of ever in its history.

What on earth happened to diplomacy, mediation, secret backstage meetings, decent intelligence gathering, to the idea of media and journalism, to people’s common sense when asking: Why do I hear the same story again and again over four years – and only one story?

Yes, there were some attempts early at a negotiated solution. But how professional were they? Did neutral mediators with knowledge about conflict-resolution, peace-making and later reconciliation participate? Were the UN’s and the OSCE’s qualified people, NGOs and individuals in that profession ever invited? The questions are purely rhetorical, I know. But they deserve to be put forward anyhow.

In my view, everyone — everyone in this conflict — suffers from a militarist mindset.

In a way, it tells us that humanity has still not learned anything from all the wars of history and that leaders everywhere have no ethical problems with accepting the mass killing of fellow human beings. Violence is still so much more statesmanship-like than peace — and being peace and conflict illiterate is perfectly OK.

And who pays the price for these elites’ militarist mindset, for their Military-Industrial-Media-

Peacelessness is the order of the day. Peace is out of politics, media and research. And therefore, we are out of peace and deep into that peacelessness. Instead of becoming more civilised over time.

And the saddest of it all?

a) None of it needed to have happened.

b) No political goal can justify this human, economic, moral and societal destruction and suffering.

c) There are still people who believe that arms lead to stability, security and peace – NATO’s mantra, no matter what it does. And if it so blatantly clear leads to more armament, increased risk of way and more stealing of resources from civil society and welfare, the solution is even more weapons.