Occupy Minneapolis

Image by P C.

After growing up in Mandan, North Dakota—a small town named after the Native Americans violently displaced to form it—moving to Minneapolis for college was the most exciting event of my life.

I fell hard for this place—for its thriving local art and music scenes; for all of its lakes encircled by parklands that keep the mansions that would otherwise privatize them at bay; for its Prince-ly history and the solidarity that stems from slogging through yet another frigid winter together; for its Midwestern common sense sensibility, the Thai food I tried for the first time, and the sense of community that perseveres despite a larger capitalist socio-economic system designed to obliterate it.

Young and naïve, surely, I assumed, this was just the beginning. If I found all this awesomeness in the first in which city I’d ever lived, bigger and better cities would certainly have even more to behold. So, upon graduating with debt and a degree, I moved to New York City in early 2011.

That fall, news began trickling out of an occupation of a small park in the Financial District. Frequently ruminating on how I’d ever pay off my student loans amid an unpaid internship and a nannying gig, Occupy Wall Street’s discourse on income and wealth inequality intrigued me to say the least.

Always a chronicler, I took the subway to Zuccotti Park to see what I could see—and what I saw was people thinking critically and creatively about the neoliberal problems facing us while taking sustained and disruptive action to claw their power back amid the astute observation that no one is coming to save us but ourselves.

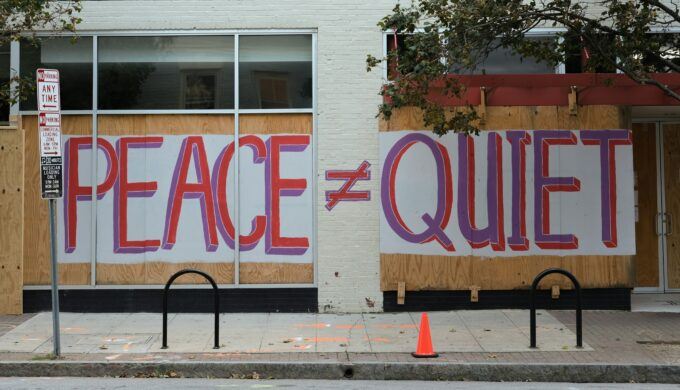

Sustained and disruptive action—exactly what’s missing from the nation-wide response to the state-sponsored horror Minneapolis has yet again sustained mere blocks from where George Floyd was slain, the state-sponsored horror that has become this county’s status quo.

To be clear in this post-truth, social media driven world defined by black and white thinking, nothing is all or nothing. It’s not that there aren’t any benefits to scheduled rallies like the ones that have been taking place in Minneapolis and beyond since Good’s murder in broad daylight. When your community is brutalized, coming together is the only way through.

But coming together for a few hours on a weekend afternoon before going back to the regularly scheduled programming of our lives—the ceaseless cycle of working and consuming in which capitalism has incarcerated us by way of having commodified the natural sustenances that are the birthright of life, human and otherwise—does nothing to disrupt the problem that is the status quo.

Stopping, however, does.

Stopping throws an intractable wrench in the gears of a system that turns on churn.

Remember what happened in those early weeks of the pandemic? Those sad and scary and confusing times that kept us inside and away from our daily lives and the reproduction of our oppression that modern living inherently accomplishes? The system and all that is too big to fail was brought to its knees in a matter of weeks. The natural world flourished in our absence and the government suddenly had the ability to immediately offer its people multiple forms of aid.

All because we simply stopped.

I’m not saying that setting up an encampment at 34th and Portland will immediately solve the problem because it won’t. What I am saying, though, is that disruption is necessary, that there’s poetry in place, and that the general strike planned for Friday the 23rd holds so much potential to be the beginning of something truly transformative.

“It will be an asterisk in the history books, if it gets a mention at all,” wrote the New York Times’ then-financial columnist, Andrew Ross Sorkin, of the Occupy movement. What Sorkin doesn’t understand is what Rebecca Solnit has so eloquently described, which is that radical change is slow and meandering rather than immediate and obvious.

In 2022, amid the Biden administration’s exploration of debt cancellation—long after I had, inspired in large part by what I saw at Occupy, attended a graduate program where my research focused on systems-level social change—I was commissioned by YES! Magazine to write a piece that explored the debt cancellation movement and the solutions powering it. What I found through interviews and research was that the debt cancellation movement was birthed by Occupy.

“The endgame here is to put potential power, the potential collective leverage of debt, into the hands of debtors to actually change the systems that indebted us in the first place,” Hannah Appel—an economic anthropologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, who participated in Occupy and went on to start a nationwide debt resistance movement called Strike Debt—told me for the story.

I argue that it is this kind of systems-level thinking—about power, collective leverage, and the systems that put and keep us in this predicament in the first place—taking place in the place where Good lost her life would be one way, one important way, to make the most of the tragedy of Good’s death. Because Good—like Floyd and Taylor and Garner and Peltier and too many to name here—was sacrificed at the altar of unchecked power.

But what power remains if we, en masse, refuse to further participate in the system in which it travels? What if the 23rd was just the beginning?

I thought a lot in my University of Minnesota days characterized by tuition hikes that continue to this day about what would happen if its more than 50,000 Twin Cities students simply stopped paying tuition. How would the university pay its president’s handsome salary and cover the costs of its coveted research institutions without our debt? Individually students don’t have any power, but collectively we had (and U of M students still have) the power to bring the institution to its knees.

Today, a hair under 10 years after I moved back to the city that marveled me once I realized with the wisdom of time that the specialness I thought I’d find everywhere was actually unique to this slice of Dakota land, I wonder what would happen if—and here I’m talking chiefly about those of us who have benefitted enough from this system in order to make sacrifices and take risks—the 23rd was just the beginning?

What if we didn’t go back to work on Monday? What if we stopped paying our rent and mortgages? If we stopped consuming and shared what we have among each other instead? What if we refused to pay taxes to a government that is terrorizing us? What if an encampment at 34th and Portland stood as a symbol of, and a hub for, our absolute refusal to continue to participate in the systems that oppress us? What if, in this way, we honored Good’s poetry with poetry in place?

What if that’s how we came together? What if we made this time the time from which we can’t—we won’t—go back to the status quo? What if this time is the time that we finally decide enough is enough—that we won’t allow murderers to gas our kids as they leave school? That we simply will not participate anymore? That Friday can only be a beginning, not an end in and of itself?

I argue that Minneapolis, still home to the thick sense of community that made me fall in love with it in the first place, was made for this moment.

Despite the media industry and the country at large having had the audacity to dub everything that lies between Silicon Valley and the original colonies as “flyover country”—a hapless, barren land where nothing of significance takes place—nothing could be further from the truth. Minneapolis and the Midwest more broadly exist on long-occupied land that’s been home to a resistance of the injustices of the United States for practically as long as the country has existed.

The Lakota and their battle for He Sapa (otherwise known as so-called South Dakota’s Black Hills) started in the 1800s and continues to this day. Some 50 miles from where I grew up, the protests that rang out from the Standing Rock reservation and the encampments erected there were heard around the world. Minneapolis birthed the American Indian Movement that advocated for Indigenous self-determination and against police brutality back in the ‘70s and remains home to George Floyd Square. Land, and the occupation of it, is, and always has been, central to resistance.

For a yet-to-be-published piece, Nick Tilsen—a member of the Oglala Lakota Nation and a Grist 50 Fixer, Ashoka Fellow, multi–time Bush Fellow, Rockefeller Fellow, and founder and CEO of NDN Collective who is currently facing up to 26 years in prison because of trumped up charges via a trial set to start on the day that could be the day we refuse to return to what was before—told me this of the Standing Rock protests in which he participated in 2016: Despite NoDAPL being largely understood as an environmental issue, “the fight at Standing Rock was about Indigenous liberation. It was about human rights. It was about so much more because the Dakota Access Pipeline was just the latest colonizer in the long line of colonizers.”

ICE is just the latest oppressor in a long line of oppressors. Good is just the latest casualty in a long line of casualties we’ve suffered at the hands of the rouge state that is the United States. The injustice of her murder isn’t about ICE or Trump, it’s about the right to a truly free life that is the birthright of all life. It’s about our liberation from the oppression we’re forced to not only endure but propagate by way of merely living our lives in this system day in and day out.

That’s what needs to stop.

That’s why it’s time to occupy Minneapolis.

It’s time for us to address the systemic levels of power and oppression facing us and to understand that no one—no person, no institution, no politician, no government—is coming to save us and, therefore, that it’s up to us to save ourselves. As daunting as that may be, the first step towards our collective liberation is small and simple—it’s just stopping. Because the one thing we have that they don’t have, and can never have, is numbers.

We are the 99 percent.