Coronavirus layoffs disproportionately hurt black and Latino workers: 'It’s almost like doomsday is coming'

Deborah Barfield Berry USA TODAY 3/24/2020

WASHINGTON – Opal Foster went to work last Wednesday at a small printing company in Rockville, Maryland. By lunchtime, the graphic designer had been laid off.

The company’s main customers – private schools, entertainment venues and national museums – had closed because of the coronavirus outbreak, so business had nearly come to a halt.

The single mother, who has a son with Down syndrome, will rely on some freelancing to help make ends meet and turn to family and area food banks to help fill her cupboards.

“For the short-term, that’s the Band-Aid on the wound,” said Foster, 45, who is African American. “But that doesn’t pay my car note. That doesn’t pay my rent.”

Foster is among thousands of employees at small businesses, restaurants, hotels, bars and manufacturing companies who lost their jobs in recent days because of the pandemic. Civil rights groups worry those workers, many of whom are people of color, will be sent in a downward spiral, scraping to pay bills and feed their families.

“We know that when the economy goes into decline, people of color always bear the brunt,’’ said Teresa Candori, communications director for the National Urban League. “We will be fighting to make sure the most vulnerable communities are not an afterthought.”

Get daily COVID-19 updates in your inbox:Sign up for Coronavirus Watch now

It's unclear if Washington's recovery plans will go far enough to get these workers through the hardship. National lawmakers are at odds over what to include in Congress' latest stimulus bill aimed at providing relief for workers and businesses hit hard by the outbreak. Republicans and Democrats differ over some key provisions, including the length of time for unemployment benefits and issues like funding for food stamps.

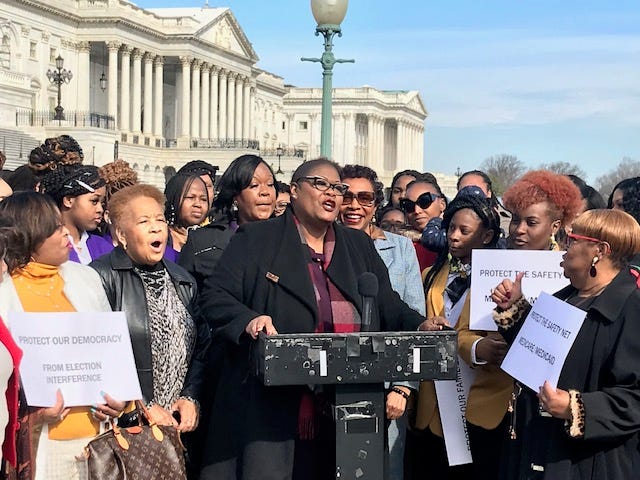

National civil rights leaders have called for a meeting with congressional leaders to push for more help for low-income workers, who are disproportionately brown and black people. Those groups historically have been overlooked or left behind by the federal government during major crises, said Melanie Campbell, president of the National Coalition on Black Civic Participation.

She called the coronavirus “an equal-opportunity pandemic.’’

“If you think about (Hurricane) Katrina, if you think about other catastrophes, a lot of times bailouts ended up taking care of the top and then it trickles down to the people,’’ Campbell said. “Our federal government has to be bold about responses as this is an ever-evolving pandemic that can become a real catastrophe for people's daily lives.”

Many blacks, Latinos, Native Americans and other communities of color saw their household wealth decline during the 2008 Great Recession and have yet to fully recover, raising questions about whether the latest financial downturn will set them back even further. The median wealth of middle-class black people dropped to $33,600 in 2013, down 47% from before the recession. For Hispanics, median wealth fell to $38,900, a 55% decline since 2007. White families saw their median wealth decline by 31% to $131,900, according to the Pew Research Center.

Census 2020:Coronavirus could make it harder to count Americans

Graphic explainer:Congress' $2 trillion coronavirus stimulus package

'It’s almost like doomsday is coming'

For some small business owners, the pandemic has meant shutting down because of local restrictions, or losing customers afraid of going about their normal routine.

On a recent afternoon, the smell of spices welcomed visitors as they walked into The Spice Suite, a quaint shop in Washington, D.C. Small glass bottles of spices lined the shelves. Olive oils in silver dispensers were stacked along one wall. Customers Janel Jackson and Kashmiere Apollon, both regulars, sniffed spices and lined them up at the cash register

A Costco-size bottle of Germ-X rested on the edge of a table at the front of the store. Apollon pressed down on the pump, squirting the sanitizer int her hands. She had heard the store would temporarily close that day.

“It’s going to be terrible,’’ she said. “So many people frequent this place.”

Angel Gregorio, the boutique's owner, had made the tough decision the night before to close for at least two months. Gregorio opened the store five years ago and won a $50,000 grant from the city last year to renovate. That work had recently been completed.

Gregorio, who is black, said uncertainly and fear of the spread of coronavirus has kept many of her customers away.

“What we’ve noticed is that folks are just not sure, just generally, about whether to leave'' their homes, Gregorio said. “And then coming to get spices, it’s like ‘I used to come out specifically for the Spice Suite but since I’m in the grocery store and been in this line for two hours, I may as well just get these big-box brands while I’m here.’"

Still, she’s grateful for loyal customers who came to shop in recent days. “It’s almost like doomsday is coming, and everyone just wants to get what they can until we get further notice about how to proceed,” she said.

Gregorio said small businesses like hers will need financial aid from federal, state and local governments to help recover and make “our employees whole.”

Closing the store has a ripple effect.

Lynette Jefferies, owner of My Desserts Diva, sells her baked goods, including peach pound cake and sweet potato tarts, out of Spice Suites. She’s among the 20 black women who sell their goods at the shop.

Jefferies said this would probably be her last time sellingdesserts in person for a while. She plans to focus on online sales and take advantage of the time shut indoors to work on an e-cookbook.

“It hurts a lot,’’ she said. “This is my livelihood. This is how I pay my bills.’’

Unemployment:US weekly jobless claims jump amid coronavirus layoffs

More:Unemployment claims, a gauge of layoffs, may hit record 2.5M this week

'I'm heartbroken'

Other small-business owners weren't sure whether they should close their doors and start letting workers go.

Kookie Park spent the weekend weighing whether to open her cafe in downtown Washington, D.C., this week. With many of her regulars working from home because of the coronavirus, the number of customers coming to buy fried chicken wings, fried fish and other popular items off the hot buffet has dropped from about 600 a day to barely 100 by the end of last week.

“Day by day, and I'm losing more people because now people are not coming to work,’’ said Park, who along with her husband, Dae Kim, owns the Cornerstone Cafe.

There was much less food to prepare, so only half of Park’s eight workers were called into work. With nearby hotels expected to shut down, she expects ever fewer customers.

We'll help you manage your finances like a pro during the coronavirus crisis:Sign up for The Daily Money now

Park plans to pay her workers, all of whom are Latinos, for at least the next two weeks. After that, she’s not sure.

“I'm heartbroken,’’ said Park, who is Korean American. “I mean, I have to pay rent myself, too, so I'm worried about that, too. But as a boss, I want to take care of them because they've been working with me such a long time and I want to go through this hard time together. ... They have their own families, so it's kind of hard for them, too.''

Park is hoping the city will help small businesses like hers and Congress will step up with aid. The last time the cafe suffered was when the federal government shutdown in 2018. That was a long 35 days, but it wasn’t like this.

“This time, I'm not sure,’’ she said. “I don't know because nobody knows.”

Many people can't work from home

Experts said it’s unclear how many jobs will be lost because of the outbreak. But many who have already lost their jobs and who could lose their jobs soon include service workers and other jobs that are disproportionately done by people of color, they said.

The number of people filing for unemployment benefits increased last week by 70,000 to 281,000, according to a Labor Department report. It attributed the initial jump to COVID-19 and cited layoffs in various fields, including hotel and restaurants.

Many people of color are in jobs that don’t have the option of working at home, said Danyelle Solomon, vice president of Race and Ethnicity Policy at Center for American Progress.

“You can't really work from home if you're waiting tables, cooking, taking care of folks as a home aide, or the health care workers who are in the hospitals right now,’’ said Solomon, co-author of a report released last week on the pandemic and its impact on the racial wealth gap.

According to the CAP report, 16% of Latino workers and 20% of black workers are able to work from home, compared with 30% of white workers.

The report also found that black, Asians and Latinos are overrepresented in typically low-paying jobs in the restaurant and hotel fields. Nearly 14% of workers in the accommodation and food services fields are Vlack and 27% are Latino, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor statistics.

A case for increasing current jobless benefits:We helped jobless workers survive the Great Recession. Here's what to do on coronavirus.

Those jobs often don’t offer comprehensive health care and other benefits, such as 401(k) and paid sick leave, Solomon said.

“People of color were not sitting in the best economic situation to begin with and this pandemic is only going to exacerbate that problem,’’ she said.

She said those workers can't respond to "economic shocks," whether it's dealing with a flat tire or losing a job because of a pandemic.

"It's much harder for you to weather that storm if you don't have those extra resources that folks with wealth have," she said.

Communities of color were particularly hard-hit during the 2008 recession, and some are still struggling from that, said Shaomeng Jia, an economics professor at Alabama State University.

People at an economic disadvantage are “already not doing so great in a good day, let alone in a rainy day,’’ he said.

Jose Ricardo is already bracing to dip into his savings to pay next month’s bills for his mobile home in Chula Vista, California. Ricardo, a waiter at a Japanese restaurant in San Diego, is working only 16 hours a week, down from the usual 32 hours two weeks ago.

“I’m really nervous,’’ said Ricardo, 61. “We are used to working hard.”

With new restrictions on restaurants to serve takeout only, Richardo no longer has the extra income from tips. He makes $12 an hour.

“People pay tips because they get a service. We’re taking care of them,’’ he said. “Now, with takeout, they pick it up and bye-bye.”

Ricardo, who lives with his wife, mother-in-law and two children, said he’s anxiously waiting to see how lawmakers will help him and other workers. But he’s worried about his co-workers, who are undocumented and won’t get that help.

Still, he’s holding out hope. “We will recover for sure,” he said.

In Native American lands, the economic pains of the coronavirus has been felt as fewer tourists visit, forcing the closures of some restaurants, museums, cultural centers and gaming operations, said Kevin Allis, head of the National Congress of American Indians.

“Not only do the businesses shut down, no longer providing income for tribal governments to run its programs, almost all the employees are tribal members,’’ said Allis of the Forest County Potawatomi community in Wisconsin. “So when these places shut down, not only now does the government have no more money coming to it, it experiences an enormous unemployment rate that further cripples and has a catastrophic effect on these particular communities.”

'You can only find jobs if they're there'

Foster, who was recently laid off from the small printing company, plans to post her resume online but is sure that because of the outbreak, many companies won’t be conducting in-person interviews until at least May. That’s if they’re hiring at all.

“You can only find jobs if they are there,” said Foster, who lives in Silver Spring, Maryland. “I’ll keep trying.”

Though her now former boss promised to put her and others back to work when the economy starts up again, Foster said she needs a salary now.

A day after being laid off, she hurried to get her root canal – two of them – before her benefits run out at the end of the month.

Meanwhile, she’s putting on hold plans to take her son, Jeremiah, to Legoland in Florida this summer. It would have been their first “true’’ vacation, she said. The amusement park might not even be open by then – plus, she said, she has to stretch the little savings she has.

“We didn’t have a whole lot extra, but we were making it,’’ she said. “Ironically, we were just kind of getting on track when the rug was pulled out from under us.”

Contributing: Nichelle Smith

No comments:

Post a Comment