Initial results amid record low turnout suggest that the grievances that drove people to the streets in 2019 are unlikely to be addressed.

Iraq's Shia groups have dominated governments and government formation since the US-led invasion of 2003 that toppled Sunni leader Saddam Hussein

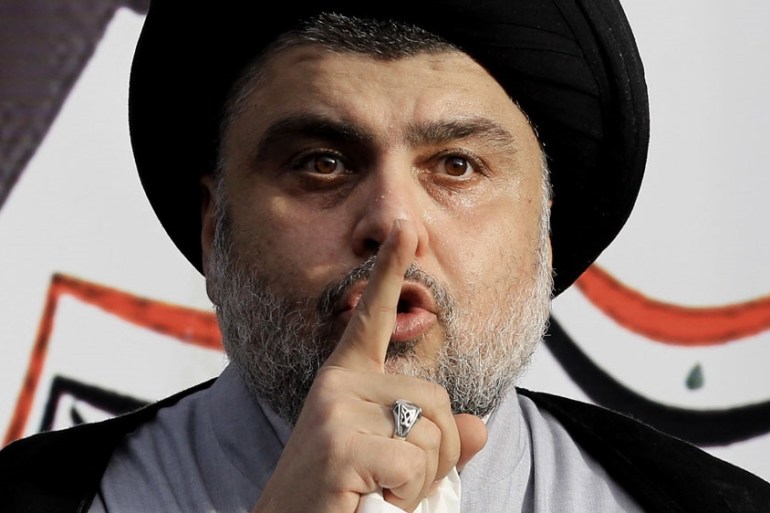

[File: Karim Kadim/AP]

11 Oct 2021

Shia Muslim religious leader Muqtada al-Sadr’s party is set to be the biggest winner in Iraq’s parliamentary election, increasing the number of seats he holds, according to initial results, officials and a spokesperson for the Sadrist Movement.

Former prime minister Nouri al-Maliki looked set to have the next largest win among Shia parties, the initial results showed on Monday.

Iraq’s Shia groups have dominated governments and government formation since the US-led invasion of 2003 that toppled Sunni leader Saddam Hussein and catapulted the Shia majority and the Kurds to power.

Sunday’s election was held several months early, in response to mass protests in 2019 that toppled a government and showed widespread anger against political leaders whom many Iraqis said have enriched themselves at the expense of the country.

But a record low turnout of 41 percent suggested that an election billed as an opportunity to wrest control from the ruling elite would do little to dislodge sectarian religious parties in power since 2003.

A count based on initial results from several Iraqi provinces plus the capital Baghdad, verified by local government officials, suggested al-Sadr had won more than 70 seats, which if confirmed could give him considerable influence in forming a government.

A spokesperson for al-Sadr’s office said the number was 73 seats. Local news outlets published the same figure.

An official at Iraq’s electoral commission said al-Sadr had come first but did not immediately confirm how many seats his party had won.

The initial results also showed that pro-reform candidates who emerged from the 2019 protests had gained several seats in the 329-member parliament.

Iran-backed parties with links to militias accused of killing some of the nearly 600 people who died in the protests took a blow, winning fewer seats than in the last election in 2018, according to the initial results and local officials.

Al-Sadr has increased his power over Iraq since coming first in the 2018 election where his coalition won 54 seats.

The unpredictable populist religious leader has been a dominant figure and often kingmaker in Iraqi politics since the US invasion.

He has opposed all foreign interference in Iraq, whether by the United States, against which he fought an armed uprising after 2003, or by neighbouring Iran, which he has criticised for its close involvement in Iraqi politics.

Al-Sadr, however, is regularly in Iran, according to officials close to him, and has called for the withdrawal of US troops from Iraq, where Washington maintains a force of about 2,500 in a continuing fight against ISIL (IS

Speaking from Baghdad, Iraq analyst Ali Anbori said that al-Sadr’s victory was not a surprise.

“Muqtada has been working a great deal to win a lead in the election. They [the Sadrists] have a good election machine, and they use all kinds of means to achieve their goals,” Anbori told Al Jazeera.

“Also, Muqtada isn’t so far away from Iran himself. Eventually, all groups will sit together and form a government under the umbrella of the Iranian regime,” he added.

“Muqtada has been the main political player in Iraq since 2005,” said Anbori, explaining that no Iraqi prime minister has taken that position without the tacit consent of al-Sadr.

Anbori said however that with “al-Sadr and his group being influential players accused of corruption,” he did not expect al-Sadr to address people’s grievances that took them the streets during the 2019 protest movement.

New law, same big parties

Elections in Iraq since 2003 have been followed by protracted negotiations that can last months and serve to distribute government posts among the dominant parties.

The result on Monday is not expected to dramatically alter the balance of power in Iraq or in the wider region.

Sunday’s vote was held under a new law billed by Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi as a way to loosen the grip of established political parties and pave the way for independent, pro-reform candidates. Voting districts were made smaller, and the practice of awarding seats to lists of candidates sponsored by parties was abandoned.

But many Iraqis did not believe the system could be changed and chose not to vote.

The official turnout figure of just 41 percent suggested the vote had failed to capture the imagination of the public, especially younger Iraqis who demonstrated in huge crowds two years ago.

“I did not vote. It’s not worth it,” Hussein Sabah, 20, told the Reuters news agency in Iraq’s southern port Basra. “There is nothing that would benefit me or others. I see youth that have degrees with no jobs. Before the elections, [politicians] all came to them. After the elections, who knows?”

Al-Kadhimi’s predecessor Adel Abdul Mahdi resigned after security forces and gunmen killed hundreds of protesters in 2019 in a crackdown on demonstrations. The new prime minister called the vote months early to show that the government was responding to demands for more accountability.

In practice, powerful parties proved best able to mobilise supporters and candidates effectively, even under the new rules.

Iraq has held five parliamentary elections since the fall of Saddam. Rampant sectarian violence unleashed during the US occupation has abated, and ISIL fighters who seized a third of the country in 2014 were defeated in 2017.

But many Iraqis say their lives have yet to improve. Infrastructure lies in disrepair and healthcare, education and electricity are inadequate.

11 Oct 2021

Shia Muslim religious leader Muqtada al-Sadr’s party is set to be the biggest winner in Iraq’s parliamentary election, increasing the number of seats he holds, according to initial results, officials and a spokesperson for the Sadrist Movement.

Former prime minister Nouri al-Maliki looked set to have the next largest win among Shia parties, the initial results showed on Monday.

Iraq’s Shia groups have dominated governments and government formation since the US-led invasion of 2003 that toppled Sunni leader Saddam Hussein and catapulted the Shia majority and the Kurds to power.

Sunday’s election was held several months early, in response to mass protests in 2019 that toppled a government and showed widespread anger against political leaders whom many Iraqis said have enriched themselves at the expense of the country.

But a record low turnout of 41 percent suggested that an election billed as an opportunity to wrest control from the ruling elite would do little to dislodge sectarian religious parties in power since 2003.

A count based on initial results from several Iraqi provinces plus the capital Baghdad, verified by local government officials, suggested al-Sadr had won more than 70 seats, which if confirmed could give him considerable influence in forming a government.

A spokesperson for al-Sadr’s office said the number was 73 seats. Local news outlets published the same figure.

An official at Iraq’s electoral commission said al-Sadr had come first but did not immediately confirm how many seats his party had won.

The initial results also showed that pro-reform candidates who emerged from the 2019 protests had gained several seats in the 329-member parliament.

Iran-backed parties with links to militias accused of killing some of the nearly 600 people who died in the protests took a blow, winning fewer seats than in the last election in 2018, according to the initial results and local officials.

Al-Sadr has increased his power over Iraq since coming first in the 2018 election where his coalition won 54 seats.

The unpredictable populist religious leader has been a dominant figure and often kingmaker in Iraqi politics since the US invasion.

He has opposed all foreign interference in Iraq, whether by the United States, against which he fought an armed uprising after 2003, or by neighbouring Iran, which he has criticised for its close involvement in Iraqi politics.

Al-Sadr, however, is regularly in Iran, according to officials close to him, and has called for the withdrawal of US troops from Iraq, where Washington maintains a force of about 2,500 in a continuing fight against ISIL (IS

Speaking from Baghdad, Iraq analyst Ali Anbori said that al-Sadr’s victory was not a surprise.

“Muqtada has been working a great deal to win a lead in the election. They [the Sadrists] have a good election machine, and they use all kinds of means to achieve their goals,” Anbori told Al Jazeera.

“Also, Muqtada isn’t so far away from Iran himself. Eventually, all groups will sit together and form a government under the umbrella of the Iranian regime,” he added.

“Muqtada has been the main political player in Iraq since 2005,” said Anbori, explaining that no Iraqi prime minister has taken that position without the tacit consent of al-Sadr.

Anbori said however that with “al-Sadr and his group being influential players accused of corruption,” he did not expect al-Sadr to address people’s grievances that took them the streets during the 2019 protest movement.

New law, same big parties

Elections in Iraq since 2003 have been followed by protracted negotiations that can last months and serve to distribute government posts among the dominant parties.

The result on Monday is not expected to dramatically alter the balance of power in Iraq or in the wider region.

Sunday’s vote was held under a new law billed by Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi as a way to loosen the grip of established political parties and pave the way for independent, pro-reform candidates. Voting districts were made smaller, and the practice of awarding seats to lists of candidates sponsored by parties was abandoned.

But many Iraqis did not believe the system could be changed and chose not to vote.

The official turnout figure of just 41 percent suggested the vote had failed to capture the imagination of the public, especially younger Iraqis who demonstrated in huge crowds two years ago.

“I did not vote. It’s not worth it,” Hussein Sabah, 20, told the Reuters news agency in Iraq’s southern port Basra. “There is nothing that would benefit me or others. I see youth that have degrees with no jobs. Before the elections, [politicians] all came to them. After the elections, who knows?”

Al-Kadhimi’s predecessor Adel Abdul Mahdi resigned after security forces and gunmen killed hundreds of protesters in 2019 in a crackdown on demonstrations. The new prime minister called the vote months early to show that the government was responding to demands for more accountability.

In practice, powerful parties proved best able to mobilise supporters and candidates effectively, even under the new rules.

Iraq has held five parliamentary elections since the fall of Saddam. Rampant sectarian violence unleashed during the US occupation has abated, and ISIL fighters who seized a third of the country in 2014 were defeated in 2017.

But many Iraqis say their lives have yet to improve. Infrastructure lies in disrepair and healthcare, education and electricity are inadequate.

No comments:

Post a Comment