December 16, 2021

In October, the UK government released two different strategies on how to achieve its net zero emissions target by 2050 – the net zero strategy and the heat and buildings strategy. Although both look at how to decarbonise the UK’s economy, they also both overlook an important feature of the future of energy consumption – the demand for cooling.

The most recent report from the UN’s intergovernmental panel on climate change shows how experiencing extreme heat will become more common as the world warms, with maximum temperatures in parts of England set to increase by more than 0.4℃ per decade. This means that the need to cool buildings is a critical issue.

This cooling also needs to be done efficiently. For example, increasing insulation can reduce overheating in well-designed buildings, but it can increase overheating in others without a good ventilation system – resulting in health problems caused by pollution building up in the air. Unfortunately, the UK’s strategies haven’t properly addressed this.

Currently, the UK’s cooling energy demand is approximately 15.5 terawatt hours per year. This is energy which is mainly used in offices and shops.

Read news coverage based on evidence, not alarm.Get newsletter

The figure is only going to rise. In a worst case global warming scenario, where the planet’s surface warms by around 4℃, demand for cooling will quadruple by 2100 in the UK.

It’s also projected that 75% to 85% of UK households will install air conditioning in response to rising temperatures by the end of the century. This could increase the UK’s current monthly electricity consumption by up to 15% during the summer season.

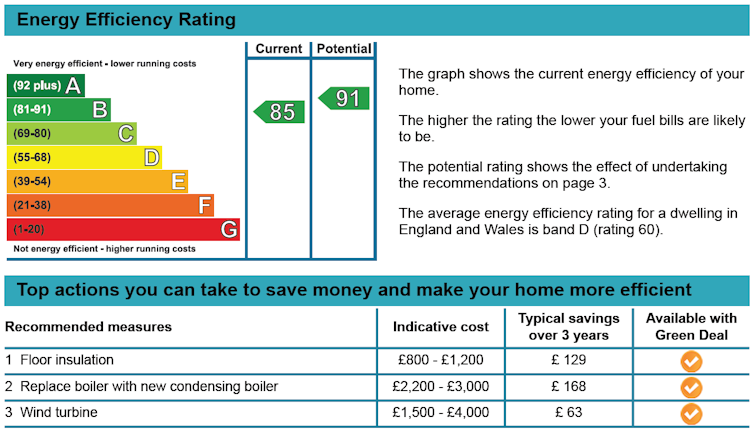

Currently, the government’s decarbonisation strategy focuses on increasing the use of energy performance certificates. These certificates – which you can now find on most buildings – provide a formal rating of how energy efficient a building is, based on things like its design and whether its energy comes from renewable or non-renewable sources. The government’s target is for all houses to achieve band C and offices to achieve band B on the scale by 2035.

Energy performance certificates help show how much energy a building uses. Naturewise/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

While these targets provide a good starting point, they’re limited in how much they can achieve. Environmental standards permitted by band C fall woefully short of those permitted by band A, allowing three times band A’s non-renewable energy consumption. And ratings are based on average climate conditions, not potential future temperatures.

Changing cooling

At the moment, reducing cooling energy demand is not explicitly part of energy policies for buildings in the UK. There need to be specific regulations making buildings comfortable to live and work in without needing extra cooling devices installed.

While these targets provide a good starting point, they’re limited in how much they can achieve. Environmental standards permitted by band C fall woefully short of those permitted by band A, allowing three times band A’s non-renewable energy consumption. And ratings are based on average climate conditions, not potential future temperatures.

Changing cooling

At the moment, reducing cooling energy demand is not explicitly part of energy policies for buildings in the UK. There need to be specific regulations making buildings comfortable to live and work in without needing extra cooling devices installed.

Older buildings can be updated to increase their sustainability. Kolforn/Wikimedia

These could include adding sun protection to windows and reflective materials to the outside of buildings to stop heat accumulating inside, or creating efficient ventilation systems that allow wind to naturally flow through buildings, removing extra heat and pollutants.

It’s not hard to make buildings significantly cooler with comparatively little effort. In one example, just adding ceiling fans to a building with air conditioning installed allowed air conditioning to comfortably be dialed back 3℃, reducing that building’s energy consumption by more than 21%. If some people are still warm, they could use devices like cooling chairs.

Once the need for cooling has been reduced as much as possible, actual cooling should be achieved with the most efficient technologies. Since cooling systems (like fans) usually run on electricity – unlike current heating systems, which are mainly based on gas – there is a huge opportunity to make cooling sustainable by fuelling it with renewable energy.

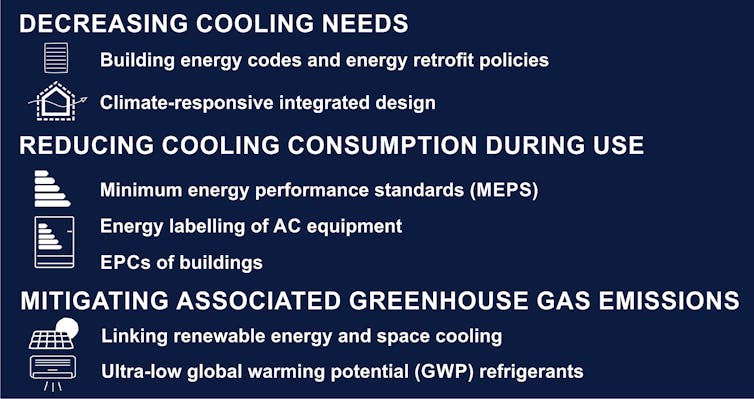

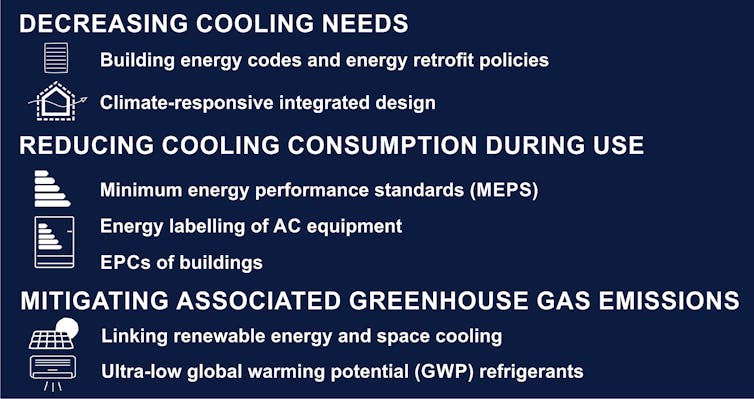

We’ve identified three main ways to reduce the environmental impact of UK cooling demand.

We’ve identified three main ways to reduce the environmental impact of UK cooling demand.

This could either be done by making energy on site, like by using roof-mounted solar panels, or by making sure that energy used to cool buildings is being sourced as sustainably as possible. Buildings can be synced up with peaks in local renewable generation – when electricity demand is low and renewable power availability high – to make cooling even greener.

Finally, fluorinated gases (F-gases) in air-conditioning units should not just be reduced or limited, as is proposed in the heat and buildings strategy, but phased out and highly penalised to force the transition to alternative clean gases.

F-gases can leak from units and quickly exacerbate global warming up to 22,800 times more than the same amount of carbon dioxide in the short term. Net zero units that use sustainable natural refrigerant gases, such as those based on propane, ammonia or isobutane, should take centre stage in the cooling market.

We have a limited window to address the future of cooling before rising temperatures push up our cooling emissions and hamper progress towards net zero targets. The future of cooling must become a present-day priority.

These could include adding sun protection to windows and reflective materials to the outside of buildings to stop heat accumulating inside, or creating efficient ventilation systems that allow wind to naturally flow through buildings, removing extra heat and pollutants.

It’s not hard to make buildings significantly cooler with comparatively little effort. In one example, just adding ceiling fans to a building with air conditioning installed allowed air conditioning to comfortably be dialed back 3℃, reducing that building’s energy consumption by more than 21%. If some people are still warm, they could use devices like cooling chairs.

Once the need for cooling has been reduced as much as possible, actual cooling should be achieved with the most efficient technologies. Since cooling systems (like fans) usually run on electricity – unlike current heating systems, which are mainly based on gas – there is a huge opportunity to make cooling sustainable by fuelling it with renewable energy.

We’ve identified three main ways to reduce the environmental impact of UK cooling demand.

We’ve identified three main ways to reduce the environmental impact of UK cooling demand.This could either be done by making energy on site, like by using roof-mounted solar panels, or by making sure that energy used to cool buildings is being sourced as sustainably as possible. Buildings can be synced up with peaks in local renewable generation – when electricity demand is low and renewable power availability high – to make cooling even greener.

Finally, fluorinated gases (F-gases) in air-conditioning units should not just be reduced or limited, as is proposed in the heat and buildings strategy, but phased out and highly penalised to force the transition to alternative clean gases.

F-gases can leak from units and quickly exacerbate global warming up to 22,800 times more than the same amount of carbon dioxide in the short term. Net zero units that use sustainable natural refrigerant gases, such as those based on propane, ammonia or isobutane, should take centre stage in the cooling market.

We have a limited window to address the future of cooling before rising temperatures push up our cooling emissions and hamper progress towards net zero targets. The future of cooling must become a present-day priority.

Radhika Khosla

Associate Professor of Sustainable Development, University of Oxford

Associate Professor of Sustainable Development, University of Oxford

Jesus Lizana

Fellow in Energy and Power, University of Oxford

Fellow in Energy and Power, University of Oxford

Disclosure statement

Jesus Lizana does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article. His research receives funding from European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme. He has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Radhika Khosla does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

No comments:

Post a Comment