Italy’s PM Mario Draghi suggests big consumers club together to limit how much is paid and raises idea of EU gas price cap

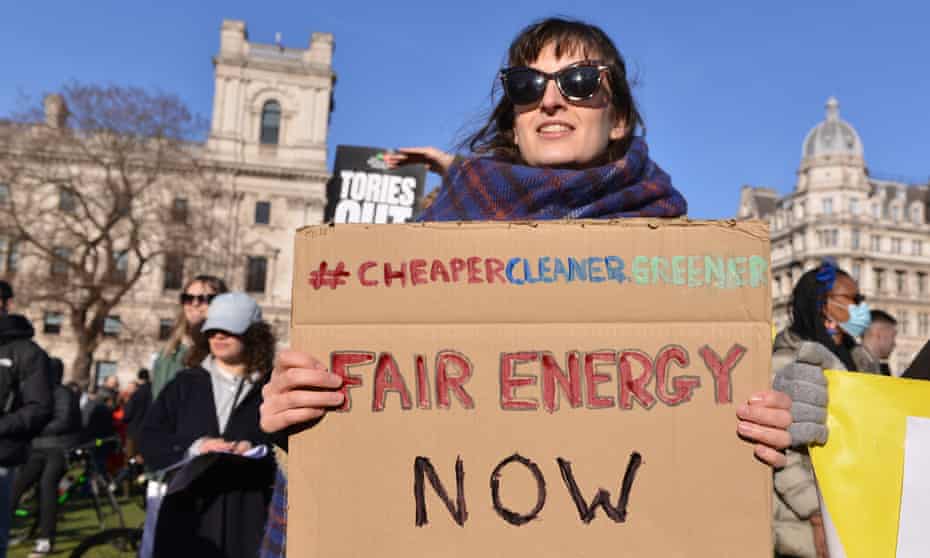

A protest against the rising cost of living in London. Draghi suggested the idea of creating a ‘cartel’ of oil consumers to counter rocketing energy prices.

Photograph: Thomas Krych/SOPA Images/Rex/Shutterstock

Jennifer Rankin in Brussels and Angela Giuffrida in Rome

Jennifer Rankin in Brussels and Angela Giuffrida in Rome

Mon 30 May 2022

Energy prices are skyrocketing as the world confronts the economic ramifications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, supply chain bottlenecks and the lingering effects of Covid-19 lockdowns. But Italy’s prime minister, Mario Draghi, has a plan.

The celebrated former European Central Bank president recently broached the idea of creating a “cartel” of oil consumers at a meeting with Joe Biden. Just as the biggest oil-producing nations club together through Opec to agree annual oil production quotas, Draghi has suggested big energy consumers join forces to increase their bargaining power.

He suggests two options: either “a cartel of buyers” working together to negotiate prices, or a “preferred path” of persuading Opec and other big producers to increase output.

Draghi and the US president also discussed implementing a cap on wholesale gas prices, an idea pushed by Italy within the EU for the past three months – although with little detail on how it would operate in practice – but opposed by Germany, the region’s biggest importer of Russian gas. In what the Italian press called “a small victory”, Draghi has managed to raise the topic for discussion at the European Council meeting taking place in Brussels on Monday and Tuesday.

Energy prices are skyrocketing as the world confronts the economic ramifications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, supply chain bottlenecks and the lingering effects of Covid-19 lockdowns. But Italy’s prime minister, Mario Draghi, has a plan.

The celebrated former European Central Bank president recently broached the idea of creating a “cartel” of oil consumers at a meeting with Joe Biden. Just as the biggest oil-producing nations club together through Opec to agree annual oil production quotas, Draghi has suggested big energy consumers join forces to increase their bargaining power.

He suggests two options: either “a cartel of buyers” working together to negotiate prices, or a “preferred path” of persuading Opec and other big producers to increase output.

Draghi and the US president also discussed implementing a cap on wholesale gas prices, an idea pushed by Italy within the EU for the past three months – although with little detail on how it would operate in practice – but opposed by Germany, the region’s biggest importer of Russian gas. In what the Italian press called “a small victory”, Draghi has managed to raise the topic for discussion at the European Council meeting taking place in Brussels on Monday and Tuesday.

European Council president Charles Michel, Italy’s prime minister Mario Draghi and France’s president Emmanuel Macron attend a summit of EU leaders on Russian oil sanctions, in Brussels.

Photograph: Johanna Geron/Reuters

“It will be discussed, and there is the possibility that the commission will then have the job of verifying the conditions of [such a scenario],” Paolo Gentiloni, European commissioner for the economy, told journalists in Rome on Monday. “But I don’t think a decision [on a gas price cap] will be made in these two days.”

Before the war 40% of EU gas and 25% of its oil came from Russia. Italy has made the cap a priority as it seeks alternative sources for its energy. The price of gas imported from Russia has leapt from €20 per megawatt-hour before the invasion of Ukraine to €120.

Since September 2021, the EU’s four largest economies – Germany, France, Italy and Spain – have each spent €20bn-€30bn to artificially lower gas and electricity bills, as well as gas and diesel prices, according to Brussels thinktank Bruegel. These subsidies undermine the EU’s support for Ukraine by helping to fund Moscow, as well as draining public finances and harming the environment.

The way to lower inflation is to directly address the issue of high gas prices, Francesco Giavazzi, Draghi’s economic adviser, said. “The point is that all forms of energy, whether from renewable sources or Russia, are currently priced in the same way,” he said. “What needs to be done is to separate the different prices as a function of the source of energy, and this is proving difficult.”

Russia uses a small fraction of its gas at home, and sends the bulk to Europe via pipelines. Once gas starts being poured from wells, you can slow the flow but not stop it. “So the position of the supplier, Russia, is relatively weak,” said Giavazzi. “They could burn the gas in the air but that would be very costly for them, like a big sanction.”

Italy has managed to get many EU states on board for a price cap, including France and Spain, but not the Netherlands or Germany. Roberto Cingolani, Italy’s minister for ecological transition, said: “Countries that oppose [the idea] defend the concept of a free market … this free market has allowed gas prices to increase five or six-fold without there being a real physical reason, for example a shortage, which has affected the cost of electricity. Citizens are unable to bear the costs, and businesses suffer the high energy costs of manufacturing.”

Yet the EU executive has rejected a cap. In a policy paper last week, the European Commission argued the proposal should only be a last resort for an emergency, such as Russia cutting off all gas to the EU. It appeared to have been swayed by analysts arguing that caps could imperil the EU’s climate goals, by blunting the signal for consumers to reduce energy demand.

Meanwhile, the proposed oil buyers’ cartel, more a priority for the US, is simply at the idea stage, but could become a mechanism to convince Opec to increase production should the EU decide to block imports of Russian energy.

Currently the EU is more focused on creating a gas-buyers’ cartel. EU leaders agreed in March to buy gas together to use the union’s heft to get better prices. “We have important leverage,” the European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, said. “So instead of outbidding each other and driving prices up, we should pull our common weight.”

The EU’s “platform for the common purchase of gas, LNG [liquified natural gas] and hydrogen” launched last month and will look at voluntary common purchase of gas, with the priority of ensuring the refilling of storage facilities. Last winter, EU gas storage fell to unusually low levels, a factor seen as exacerbating surging prices and higher bills. In the long run the group will also turn its attention to hydrogen and renewables, although details remain vague.

The EU consumes three-quarters of the world’s pipeline gas and 16% of ship-transported LNG. Inspired by the example of EU purchasing of Covid vaccines, supporters argue that EU procurement could ensure security of supply and ensure greater transparency about prices. Yet many details are yet to be worked out.

It remains unclear whether all 27 EU member states will sign up, or how easily they could exit existing gas contracts. And the EU still has to agree a law allowing it to buy energy together, which will also have to get round one of the EU’s raisons d’être: breaking up cartels.

Having the EU negotiate deals for private or public companies raises antitrust concerns, as it would put those companies dealing with the cartel in a privileged position vis-a-vis outsiders. “We have a strong antitrust authority in Europe,” says Simone Tagliapietra, a senior fellow at the Bruegel thinktank. “Now how can you create a cartel to buy gas? Probably the only way to do that is to ground the initiative on energy security measures.”

Meanwhile other plans to curb the price of crude are gaining ground. Germany’s economy minister, Robert Habeck, said last week that the commission and the US were working on a proposal to cap global prices.

Michael Bloss, a German Green MEP, says the EU should be creating an oil-consumers’ cartel with other developed countries including the EU, US, Japan and South Korea and the UK, which represent “a huge share of oil consumption” on the global market. “If they together say this is the price we are going to pay, but not more, the sellers, they will have to abide by it … This special time needs special action.”

“It will be discussed, and there is the possibility that the commission will then have the job of verifying the conditions of [such a scenario],” Paolo Gentiloni, European commissioner for the economy, told journalists in Rome on Monday. “But I don’t think a decision [on a gas price cap] will be made in these two days.”

Before the war 40% of EU gas and 25% of its oil came from Russia. Italy has made the cap a priority as it seeks alternative sources for its energy. The price of gas imported from Russia has leapt from €20 per megawatt-hour before the invasion of Ukraine to €120.

Since September 2021, the EU’s four largest economies – Germany, France, Italy and Spain – have each spent €20bn-€30bn to artificially lower gas and electricity bills, as well as gas and diesel prices, according to Brussels thinktank Bruegel. These subsidies undermine the EU’s support for Ukraine by helping to fund Moscow, as well as draining public finances and harming the environment.

The way to lower inflation is to directly address the issue of high gas prices, Francesco Giavazzi, Draghi’s economic adviser, said. “The point is that all forms of energy, whether from renewable sources or Russia, are currently priced in the same way,” he said. “What needs to be done is to separate the different prices as a function of the source of energy, and this is proving difficult.”

Russia uses a small fraction of its gas at home, and sends the bulk to Europe via pipelines. Once gas starts being poured from wells, you can slow the flow but not stop it. “So the position of the supplier, Russia, is relatively weak,” said Giavazzi. “They could burn the gas in the air but that would be very costly for them, like a big sanction.”

Italy has managed to get many EU states on board for a price cap, including France and Spain, but not the Netherlands or Germany. Roberto Cingolani, Italy’s minister for ecological transition, said: “Countries that oppose [the idea] defend the concept of a free market … this free market has allowed gas prices to increase five or six-fold without there being a real physical reason, for example a shortage, which has affected the cost of electricity. Citizens are unable to bear the costs, and businesses suffer the high energy costs of manufacturing.”

Yet the EU executive has rejected a cap. In a policy paper last week, the European Commission argued the proposal should only be a last resort for an emergency, such as Russia cutting off all gas to the EU. It appeared to have been swayed by analysts arguing that caps could imperil the EU’s climate goals, by blunting the signal for consumers to reduce energy demand.

Meanwhile, the proposed oil buyers’ cartel, more a priority for the US, is simply at the idea stage, but could become a mechanism to convince Opec to increase production should the EU decide to block imports of Russian energy.

Currently the EU is more focused on creating a gas-buyers’ cartel. EU leaders agreed in March to buy gas together to use the union’s heft to get better prices. “We have important leverage,” the European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, said. “So instead of outbidding each other and driving prices up, we should pull our common weight.”

The EU’s “platform for the common purchase of gas, LNG [liquified natural gas] and hydrogen” launched last month and will look at voluntary common purchase of gas, with the priority of ensuring the refilling of storage facilities. Last winter, EU gas storage fell to unusually low levels, a factor seen as exacerbating surging prices and higher bills. In the long run the group will also turn its attention to hydrogen and renewables, although details remain vague.

The EU consumes three-quarters of the world’s pipeline gas and 16% of ship-transported LNG. Inspired by the example of EU purchasing of Covid vaccines, supporters argue that EU procurement could ensure security of supply and ensure greater transparency about prices. Yet many details are yet to be worked out.

It remains unclear whether all 27 EU member states will sign up, or how easily they could exit existing gas contracts. And the EU still has to agree a law allowing it to buy energy together, which will also have to get round one of the EU’s raisons d’être: breaking up cartels.

Having the EU negotiate deals for private or public companies raises antitrust concerns, as it would put those companies dealing with the cartel in a privileged position vis-a-vis outsiders. “We have a strong antitrust authority in Europe,” says Simone Tagliapietra, a senior fellow at the Bruegel thinktank. “Now how can you create a cartel to buy gas? Probably the only way to do that is to ground the initiative on energy security measures.”

Meanwhile other plans to curb the price of crude are gaining ground. Germany’s economy minister, Robert Habeck, said last week that the commission and the US were working on a proposal to cap global prices.

Michael Bloss, a German Green MEP, says the EU should be creating an oil-consumers’ cartel with other developed countries including the EU, US, Japan and South Korea and the UK, which represent “a huge share of oil consumption” on the global market. “If they together say this is the price we are going to pay, but not more, the sellers, they will have to abide by it … This special time needs special action.”

No comments:

Post a Comment