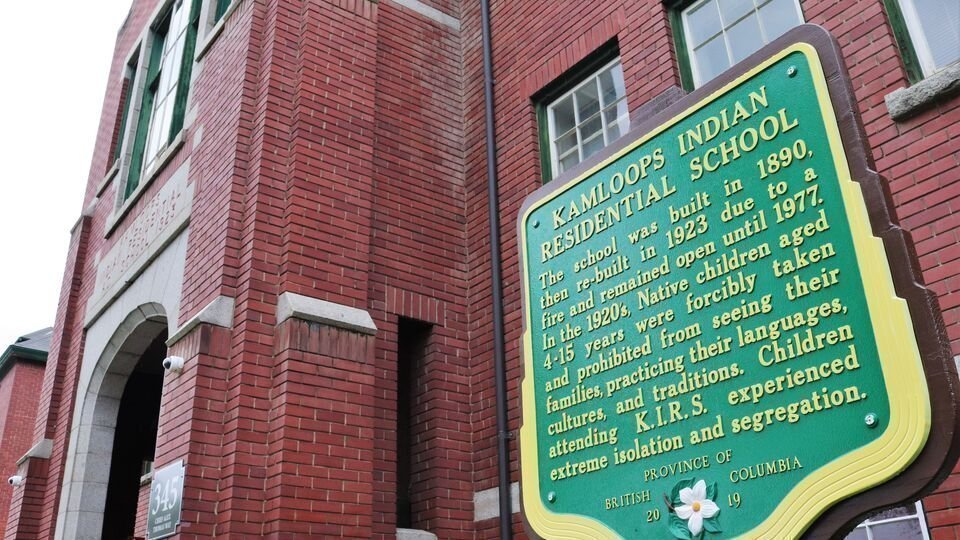

Kamploops Indian Boarding School (Photo: Change.Org)

BY LEVI RICKERT MAY 27, 2022

Opinion. A year ago, as we headed into Memorial Day weekend, news broke from British Columbia of the discovery of 215 remains of innocent school children at the Kamloops Industrial Residential School.

For those of us in Indian Country, the disclosure was a reminder of what most of us already knew for decades about Indian boarding schools, as they were known in the United States.

We knew for decades about the stories of the physical, emotional and sexual abuse suffered by many of the children who attended these schools. We knew that these children were beaten if they tried to speak their tribal languages. We knew that Native students died at these boarding schools. We knew that hundreds of graves, some unmarked, existed at these Indian boarding schools.

We knew that the children who attended Indian boarding schools were part of a federal policy that sought to assimilate Native American children under the mantra “Kill the Indian, save the man.”

Even though we knew of these gross atrocities committed against our ancestors and boarding school survivors, most non-Natives had very little or no knowledge of this federal policy up until late last May.

Kamloops woke up the world to the atrocities committed against Native children.

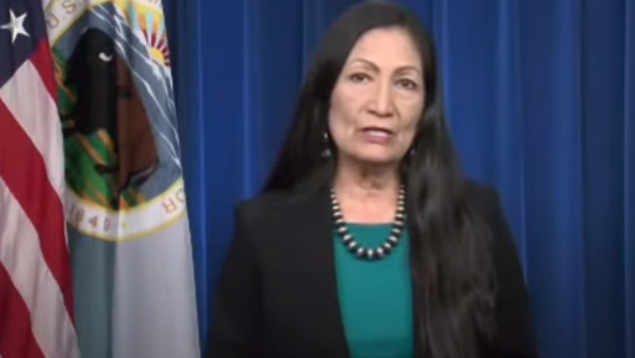

Within three weeks of the Kamloops’ announcement, U.S. Department of the Interior Secretary Deb Haaland established the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative to investigate and shed light on this dark era of cultural genocide.

Kamloops caught the attention of the national and international media. On an ongoing basis, there is so much news to be covered that large media outlets tend to take a “shiny object” approach to news. They cover stories for a short duration of time, then move on to the next new thing. The story of the children’s deaths at Kamloops became a shiny object for much of the mainstream media.

Our editorial team at Native News Online decided that as a leading national Native American publication, we would continue to cover Indian boarding schools when the subject was no longer the shiny object to the non-Native media.

We knew we had to cover various aspects of Indian boarding schools from the Native perspective. We decided we would write the articles that needed to be told about boarding schools. The scenario played out over the past year, culminating with the release of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report on May 11, 2022.

Since the Kamloops’ story broke, Native News Online has published nearly 100 articles about Indian boarding schools. In addition, we hosted several live streams to examine the topic in depth.

In a year of coverage, two stories stick out in my mind. The first article is Surviving Kuper Island Residential School: ‘I Hear Little Children Screaming in My Head’, written by Andrew Kennard, an Drake University intern. The article is about Eddie Charlie who provided vivid recollections of his time attending the Kuper Island Residential school that was located near Chemainus, British Columbia.

Charlie told of the physical beatings and even starvation. He recounted how children disappeared. Years later, he would learn over 200 children were buried at the Kuper Island Residential School. Charlie’s experiences at Kuper Island led him to attempt suicide. His recollections led our editorial staff to issue a warning to our readers due to its content.

The second article, entitled The Remains of 10 Children at the Carlisle Indian Boarding School are Returning Home, written by our senior reporter Jenna Kunze, tells the story of the repatriation of 10 children who died at the well-known boarding school located in Pennsylvania.

The story describes the long rigorous process involved having the bodies of the students exhumed and returned to their tribal communities.

As we commemorate the first year since Kamloops’ announcement, Kunze, who has been reporting from the Rosebud Indian Reservation this past week, recounts how covering the Indian boarding schools has impacted her.

“Listening to the stories of survivors, reading federal documents, and visiting Carlisle Industrial School in Pennsylvania and the former St. Francis Mission in South Dakota has changed the core of my entire understanding of reporting on Indian Country: that Indian Boarding School impacted its survivors on a genetic level, and they passed that trauma down to their children. But along with trauma, survivors also passed down resilience,” Kunze told me.

Kamloops certainly woke up the world to the subject of Indian boarding schools. The announcement provided a new spotlight on what many of us already knew, but often didn’t talk about. Now, the conversation has started and is growing louder and more insistent. More and more Native people are talking about the intergenerational impact of boarding schools on their families and their communities. And, for the first time, many non-Natives are learning about this dark period in our nation’s history.

After a year of closely covering Indian boarding schools, we are not stopping. Native News Online remains committed to providing coverage of this important issue in a way that informs, inspires and uplifts. We hope you'll join us

About The Author

Levi Rickert (Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation) is the founder, publisher and editor of Native News Online. Rickert was awarded Best Column 2021 Native Media Award for the print/online category by the Native American Journalists Association. He serves on the advisory board of the Multicultural Media Correspondents Association. He can be reached at levi@nativenewsonline.net.

INDIAN BOARDING SCHOOLS: After Kamloops, a Year of Reckoning and Initial Steps Toward Reconciliation

- BY JENNA KUNZE

WARNING: This story has details about boarding schools, assimilation and trauma. If you are feeling triggered or unsafe, here is a list of resources for trauma responses from the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

It's been a year since the news first broke about an unmarked gravesite holding the bodies of more than 200 Indigenous children who had attended a former residential school in Canada. The discovery at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia made international headlines, shining a spotlight on a dark era of forced assimilation of Indigenous children by the federal governments of Canada and the United States, with help from several Christian denominations and churches.

As communities around the world processed the news about Kamloops, many non-Indigenous leaders — including the Canadian Prime Minister and Pope Francis — expressed their shock. For most Indigenous people throughout North America, the overriding feelings were sadness and anger, but not shock.

“Absolutely not shock,” one Native leader told us. “We’ve known about this."

The assimilation and, some would say, genoicide of Native children at boarding schools may not have been a secret to Indigenous families, but it also wasn’t something that was openly discussed in many Native homes. That changed in a matter of days after the Kamloops story rocketed around the globe.

Beginning last May, Native News Online has committed its newsroom to covering Indian boarding schools and their intergenerational impacts on Native families and communities. Over the past year, we’ve produced nearly 100 stories about Indian boarding schools, traveled to former boarding school locations, and interviewed survivors and their descendants, as well as tribal leaders, boarding school researchers and government officials studying this dark period of assimilating Native children.

Since the news of Kamloops first broke, we’ve seen and reported on the remains of Indigenous children buried at former boarding schools being returned to their ancestral homes. We’ve written about the discovery of additional gravesites at other boarding schools. We witnessed Pope Francis attempting to apologize to Indigenous people for the Catholic Church’s role in the boarding school era. We tracked legislative efforts to create a Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding Schools. And we’ve watched the U.S. government take a remarkable step forward as it produced an investigative report on Indian boarding school history and admitted, for the first time, its twin-policy goal of assimilating Native youth while dispossessing their families of their land.

Native News has compiled a timeline of events below to recognize the progress and momentum Native peoples have spearheaded to truth telling, and to highlight the healing work that remains in the wake of a centuries old policy built on the words of Henry Pratt, who infamously said the goal of Indian Boarding Schools was to “kill the Indian, save the man.

May 2021

On May 27, 2021, the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation in British Columbia’s southern interior announced it had found unmarked gravesites holding the remains of at least 215 children — some as young as three-years old — on the former property of the Kamloops Indian Residential School. The tribe hired a specialist in ground-penetrating radar to find the gravesite during a site survey on its property.

While non-Natives across the world expressed shock and horror, Indigenous peoples said the findings confirmed what they’d long known.

“We had a knowing in our community that we were able to verify,” Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Chief Rosanne Casimir said at the time. “To our knowledge, these missing children are undocumented deaths.”

In both Canada and the United States, Native people demanded accountability even as they mourned, holding memorials and marches to bring visibility to the legacy of boarding schools on both sides of the border.

June 2021

Less than a month later, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo), the first-ever Native American to lead a cabinet department within the United States government, announced the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative.The initiative’s work was, in part, to investigate the work of Haaland’s predecessors at the Interior Department, which had been tasked with assimilating and eradicating Native peoples, beginning in the mid 1800s.

“For more than a century, the Interior Department was responsible for operating the Indian boarding schools across the United States and its territories,” Haaland said in an address during the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) 2021 Mid Year Conference. “We are therefore uniquely positioned to assist in the effort to recover the dark history of these institutions that have haunted our families for too long.”

The new initiative, prompted by Kamloops, directed Interior Assistant Secretary Bryan Newland and his team to comb through government records with a goal of identifying how many boarding school facilities the federal government ran or paid for, how many potential burial sites exist near the schools, and the identity of the children who were taken to the schools.

On June 5, after a meeting with two Canadian Cardinals the day before, Pope Francis spoke to a congregation in his typical Sunday morning address at Saint Peter’s Square in Vatican City. The Pope expressed “sorrow” “about the shocking discovery,” according to a translation of his prepared statement, though he offered no official apology for the role the Catholic Church played in the displacement of an estimated 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children.

Fawn Sharp, president of the National Congress of American Indians, said that, in order to apologize for something, you must first know what you’re being held accountable for.

“While we seek an apology for this instance, until we do a complete fact finding of every instance, every life that was murdered, an apology is going to be incomplete,” Sharp told Native News Online.

The same month, the Cowessess First Nation announced the discovery of as many as 751 unmarked graves at the former Marieval Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan.

July 2021

In July, the United States Army—which inherited and controls the grounds of the country’s first off-reservation Indian boarding school, called Carlisle Indian Industrial School—completed the exhumation of several Native children buried at Carlisle. These Native children died there and were never returned home to their families.

The Army, compelled by one tribal member's insistence in 2017, exhumed and returned the remains of nine Rosebud Lakota Oyate youth to their next of kin, more than 140 years after they left home.

During Carlisle’s four-decade history, roughly 7,800 Native children from nearly every tribal nation across the country were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to the Pennsylvania boarding school as part of the U.S. government’s assimilationist agenda, according to records from the Cumberland Valley Historical Society.

Today, 173 children still remain buried in the school’s former cemetery—the majority of which have records with their names and tribal affiliations. Following the return to Rosebud Lakota Oyate last year, the Army announced it would attempt to return each of the remaining children to their homelands, including those with headstones marked ‘unknown.’

Meanwhile, in Canada another 182 unmarked graves were discovered by the Lower Kootenay Band of the Ktunaxa Nation, which used ground-penetrating radar near the former St. Eugene’s Mission School in Cranbrook, British Columbia.

August 2021

Seattle’s city council passed a resolution in support of the U.S. Department of the Interior's Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative and the Truth and Healing Commission.

September 2021

The city of Albuquerque announced it will become the first U.S. city to use ground-penetrating radar to search for remains of Native American children buried in unmarked gravesites over a century ago.

Later that month on the National Day of Remembrance for U.S. Indian Boarding Schools, September 20, U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and the Co-Chairs of the Congressional Native American Caucus — U.S. Reps Sharice Davids (D-Kan.) of the Ho Chunk Nation and Tom Cole (R-Okla.) of Chickasaw Nation — reintroduced The Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies in the United States Act.

The bill, originally introduced in 2020 by then-Congresswoman Haaland, seeks healing for stolen Native children and their communities.

Specifically, the legislation would establish a formal commission to investigate, document, and acknowledge past injustices of the federal government's Indian Boarding School Policies with a wider scope than is included in the DOI’s federal initiative. The commission would also develop recommendations for Congress to aid in healing of the historical and intergenerational trauma, and provide a forum for survivors to share their boarding school stories.

December 2021

In the first public move of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, the DOI entered into an Memorandum of Understanding with the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS).

Christine Diindiisi McCleave (Citizen of the Turtle Mountain Ojibwe Nation), the CEO of NABS at the time, agreed to exclusively license Interior to use their historical research “without restriction.” NABS is the only organization with a count on how many Indian Boarding Schools were and continue to be in operation.

Additionally in December, Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak (D) apologized for the state’s role in the government’s forced assimilation of Native youth into Indian Boarding Schools.

January 2022

An increasing number of Catholic organizations join in the discussion about Indian boarding schools. Native News Online spoke with tribal leaders on what role they have to play in the pursuit of truth and healing, and who their participation is serving.

In a related story, Canada tentatively agreed to a $31 billion (U.S.) settlement to right its discriminatory child-welfare system that disproportionately separated Indigenous youth from their families over the past three decades, then chronically underfunded the welfare programs meant to serve them.

April 2022

For the first time in history, the leader of the Catholic Church acknowledged the role of the church in perpetrating harm on the more than 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children sent to residential schools in Canada.

In the nine months since Kamloops discovery, the remains of more than 1,400 Indigenous children were located at the sites of former residential schools where kids often died of disease, neglect, and abuse. The Catholic Church was responsible for running nearly three-quarters of the 130 residential schools operated across Canada.

“It's chilling to think of determined effort to instill a sense of inferiority to rob people of their cultural identity, to sever their roots, and to consider all the personal and social efforts that this continues to entail: Unresolved traumas that have become intergenerational trauma,” Pope Francis said, addressing a delegation of nearly 100 Indigenous leaders who Canadian traveled to Italy to ask for an apology this week. “All this made me feel two things very strongly: indignation and shame,” the Pope said.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland and Assistant Secretary Bryan Newland at a press conference on the Indian Boarding School Report (Courtesy NABS)

May 2022

After a two-week forum at the United Nations headquarters in New York City, the UN’s United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues adopted its final report on Friday, May 6.

Included in the report was the Forum’s decision to create a working group dedicated to truth, reconciliation, and transitional justice, including in post-conflict areas, for lasting peace that respects the rights of Indigenous Peoples and promotes their full and effective inclusion, including Indigenous women.

The U.S. Department of the Interior on May 11 released its initial findings after a nine-month investigation into the fraught legacy of Indian Boarding Schools that the U.S. government ran or supported for a century and a half.

The 106-page report—penned by Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs Bryan Newland—details for the first time that the federal government operated or supported 408 boarding schools across 37 states, including Alaska and Hawai’i, between 1819 and 1969.

About half of the boarding schools were staffed or paid for by a religious institution. The investigation identified at least 500 children in marked and unmarked burial sites at 53 of those schools, though the DOI expects to find the number of children buried at boarding schools across the nation to be in the “thousands or tens of thousands,” as the investigation continues.

“This report, as I see it, is only a first step to acknowledge the experiences of Federal Indian boarding school children,” Newland wrote. He recommended a second report that specifically focuses on investigative findings of locations of marked or unmarked burial sites associated with the Federal Indian boarding school system; names, ages, and tribal affiliations of children interred at such locations; and an estimation of federal dollars spent supporting the Federal Indian boarding school system as well as Native land held in trust by the United States used to support the Federal Indian boarding school system.

Simultaneously, Haaland announced her year-long Road To Healing tour that will take her across the country to connect with and listen to boarding school survivors’ stories.

“Recognizing the impacts of the federal Indian boarding school system cannot just be a historical reckoning,” Haaland said. “We must also chart a path forward to deal with these legacy issues.”

While many across Indian Country rejoice over the past year’s progress in shedding light on the history of Indian boarding schools, they say we’re still at the very beginning of a long road.

“It is good news to hear that federal Indian boarding schools are being investigated at such a high level,” American Indian Movement Grand Governing Council Co-Chair Lisa Bellanger told Native News Online. “There is an intense amount of work that needs to happen to bring our children home.”

Access our collection of Native News Online coverage of Indian Boarding Schools since May 2021.

About The Author

Jenna Kunze

Staff Writer

Jenna Kunze is a reporter for Native News Online and Tribal Business News. Her bylines have appeared in The Arctic Sounder, High Country News, Indian Country Today, Smithsonian Magazine and Anchorage Daily News. In 2020, she was one of 16 U.S. journalists selected by the Pulitzer Center to report on the effects of climate change in the Alaskan Arctic region. Prior to that, she served as lead reporter at the Chilkat Valley News in Haines, Alaska. Kunze is based in New York.

No comments:

Post a Comment