Frederick Douglass on ‘Regarding Slavery as the Basis of Wealth’

He found that Black workers in the North lived better than most slaveholders he’d seen in the South

Groundhog Notes

Jul 11,2022

Dear Readers:

In The UnPopulist’s Fourth of July offering, the inimitable Deirdre McCloskey, bard of the liberal market economy, probed history and economics to demonstrate that but for slavery, America would have been even richer today. That horrible institution was not the true engine of the United States’ extraordinary economic growth, contrary to the belief in progressive circles. In particular, she discussed the sudden and dramatic increase in personal wealth that occurred not with the spread of slavery, but with the rise of liberalism’s signature belief that all men are created equal and endowed with certain inalienable rights. These rights included, as McCloskey put it, the “equal liberty of ordinary people to have a go” at a livelihood without the permission of lords and kings. This freedom was antithetical to slavery.

McCloskey’s piece quickly became one of TU’s most popular commentaries. Moreover, it sent our resident Groundhog burrowing through TU’s library, excitedly reminding us that a great American had chronicled the striking difference between slavery and a more liberal marketplace over 160 years ago.

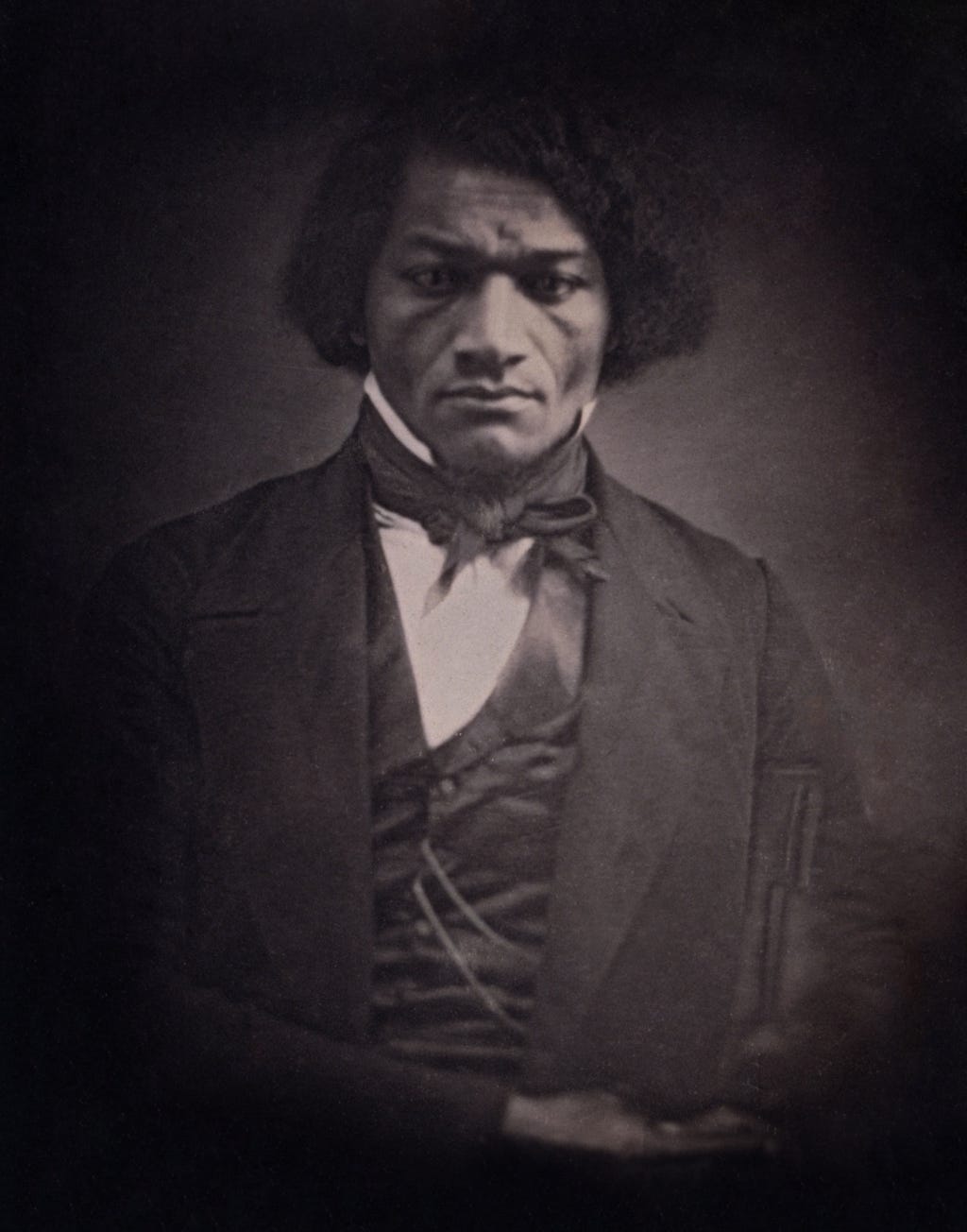

Hence we offer the following excerpt from My Bondage and My Freedom, the second autobiography of Frederick Douglass, an ex-slave whose penetrating speeches and writings rendered him the liberal conscience of 19th century America. This passage describes Douglass’ impressions upon arriving at the port of New Bedford, Massachusetts, just weeks after his escape from slavery in Maryland in 1838. New Bedford residents often discriminated against Black people, as Douglass observed elsewhere in the book, but the contrast with slavery was unmistakable. “I was now living in a new world,” he wrote, “and was wide awake to its advantages.”

These advantages prompted Douglass to reflect on their source. His conclusions anticipate McCloskey’s thesis about the revolutionary right to choose one’s trade and keep one’s earnings—and they do so in the forceful, straightforward style that established his fame. You’ll want to read on.

Tom Shull

Editor-at-Large

Twitter: @thomasashull

retouched by Scewing: Wikimedia Commons

The reader will be amused at my ignorance, when I tell the notions I had of the state of northern wealth, enterprise, and civilization. Of wealth and refinement, I supposed the north had none. …

The impressions I had received were all wide of the truth. New Bedford, especially, took me by surprise, in the solid wealth and grandeur there exhibited.

I had formed my notions respecting the social condition of the free states, by what I had seen and known of free, white, non-slaveholding people in the slave states. Regarding slavery as the basis of wealth, I fancied that no people could become very wealthy without slavery. A free white man, holding no slaves, in the country, I had known to be the most ignorant and poverty-stricken of men, and the laughing stock even of slaves themselves—called generally by them, in derision, “poor white trash.” Like the non-slaveholders at the south, in holding no slaves, I suppose the northern people like them, also, in poverty and degradation.

Judge, then, of my amazement and joy, when I found—as I did find—the very laboring population of New Bedford living in better houses, more elegantly furnished—surrounded by more comfort and refinement—than a majority of the slaveholders on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. There was my friend, Mr. Johnson, himself a colored man, (who at the south would have been regarded as a proper marketable commodity), who lived in a better house—dined at a richer board—was the owner of more books—the reader of more newspapers—was more conversant with the political and social condition of this nation and the world—than nine-tenths of all the slaveholders of Talbot county, Maryland. Yet Mr. Johnson was a working man, and his hands were hardened by honest toil.

Here, then, was something for observation and study. Whence the difference? The explanation was soon furnished, in the superiority of mind over simple brute force. Many pages might be given to the contrast, and in explanation of its causes. But an incident or two will suffice to show the reader as to how the mystery gradually vanished before me.

My first afternoon, on reaching New Bedford, was spent in visiting the wharves and viewing the shipping. The sight of the broad brim and the plain, Quaker dress, which met me at every turn, greatly increased my sense of freedom and security. “I am among the Quakers,” thought I, “and am safe.” Lying at the wharves and riding in the stream, were full-rigged ships of finest model, ready to start on whaling voyages. Upon the right and the left, I was walled in by large granite-fronted warehouses, crowded with the good things of this world. On the wharves, I saw industry without bustle, labor without noise, and heavy toil without the whip. There was no loud singing, as in southern ports, where ships are loading or unloading—no loud cursing or swearing—but everything went on as smoothly as the works of a well adjusted machine.

How different was all this from the noisily fierce and clumsily absurd manner of labor-life in Baltimore and St. Michael’s [Maryland]! One of the first incidents which illustrated the superior mental character of northern labor over that of the south, was the manner of unloading a ship’s cargo of oil. In a southern port, twenty or thirty hands would have been employed to do what five or six did here, with the aid of a single ox attached to the end of a fall. Main strength, unassisted by skill, is slavery’s method of labor. An old ox, worth eighty dollars, was doing, in New Bedford, what would have required fifteen thousand dollars’ worth of human bones and muscles to have performed in a southern port.

I found that everything was done here with a scrupulous regard to economy, both in regard to men and things, time and strength. The maid servant, instead of spending at least a tenth part of her time in bringing and carrying water, as in Baltimore, had the pump at her elbow. The wood was dry, and snugly piled away for winter. Woodhouses, in-door pumps, sinks, drains, self-shutting gates, washing machines, pounding barrels, were all new things, and told me that I was among a thoughtful and sensible people. To the ship-repairing dock I went, and saw the same wise prudence. The carpenters struck where they aimed, and the calkers wasted no blows in idle flourishes of the mallet. I learned that men went from New Bedford to Baltimore, and bought old ships, and brought them here to repair, and made them better and more valuable than they ever were before. Men talked here of going whaling on a four years’ voyage with more coolness than sailors where I came from talked of going a four months’ voyage.

I now find that I could have landed in no part of the United States, where I should have found a more striking and gratifying contrast to the condition of the free people of color in Baltimore, than I found here in New Bedford. No colored man is really free in a slaveholding state. He wears the badge of bondage while nominally free, and is often subjected to hardships to which the slave is a stranger; but here in New Bedford, it was my good fortune to see a pretty near approach to freedom on the part of the colored people. I was taken all aback when Mr. Johnson—who lost no time in making me acquainted with the fact—told me that there was nothing in the constitution of Massachusetts to prevent a colored man from holding any office in the state. There, in New Bedford, the black man’s children—although anti-slavery was then far from popular—went to school side by side with the white children, and apparently without objection from any quarter.

To make me at home, Mr. Johnson assured me that no slaveholder could take a slave from New Bedford; that there were men there who would lay down their lives, before such an outrage could be perpetrated. The colored people themselves were of the best metal, and would fight for liberty to the death.

This text was taken from Chapter 22 of Frederick Douglass’ autobiography My Bondage and My Freedom, available at the website Lit2Go.

The reader will be amused at my ignorance, when I tell the notions I had of the state of northern wealth, enterprise, and civilization. Of wealth and refinement, I supposed the north had none. …

The impressions I had received were all wide of the truth. New Bedford, especially, took me by surprise, in the solid wealth and grandeur there exhibited.

I had formed my notions respecting the social condition of the free states, by what I had seen and known of free, white, non-slaveholding people in the slave states. Regarding slavery as the basis of wealth, I fancied that no people could become very wealthy without slavery. A free white man, holding no slaves, in the country, I had known to be the most ignorant and poverty-stricken of men, and the laughing stock even of slaves themselves—called generally by them, in derision, “poor white trash.” Like the non-slaveholders at the south, in holding no slaves, I suppose the northern people like them, also, in poverty and degradation.

Judge, then, of my amazement and joy, when I found—as I did find—the very laboring population of New Bedford living in better houses, more elegantly furnished—surrounded by more comfort and refinement—than a majority of the slaveholders on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. There was my friend, Mr. Johnson, himself a colored man, (who at the south would have been regarded as a proper marketable commodity), who lived in a better house—dined at a richer board—was the owner of more books—the reader of more newspapers—was more conversant with the political and social condition of this nation and the world—than nine-tenths of all the slaveholders of Talbot county, Maryland. Yet Mr. Johnson was a working man, and his hands were hardened by honest toil.

Here, then, was something for observation and study. Whence the difference? The explanation was soon furnished, in the superiority of mind over simple brute force. Many pages might be given to the contrast, and in explanation of its causes. But an incident or two will suffice to show the reader as to how the mystery gradually vanished before me.

My first afternoon, on reaching New Bedford, was spent in visiting the wharves and viewing the shipping. The sight of the broad brim and the plain, Quaker dress, which met me at every turn, greatly increased my sense of freedom and security. “I am among the Quakers,” thought I, “and am safe.” Lying at the wharves and riding in the stream, were full-rigged ships of finest model, ready to start on whaling voyages. Upon the right and the left, I was walled in by large granite-fronted warehouses, crowded with the good things of this world. On the wharves, I saw industry without bustle, labor without noise, and heavy toil without the whip. There was no loud singing, as in southern ports, where ships are loading or unloading—no loud cursing or swearing—but everything went on as smoothly as the works of a well adjusted machine.

How different was all this from the noisily fierce and clumsily absurd manner of labor-life in Baltimore and St. Michael’s [Maryland]! One of the first incidents which illustrated the superior mental character of northern labor over that of the south, was the manner of unloading a ship’s cargo of oil. In a southern port, twenty or thirty hands would have been employed to do what five or six did here, with the aid of a single ox attached to the end of a fall. Main strength, unassisted by skill, is slavery’s method of labor. An old ox, worth eighty dollars, was doing, in New Bedford, what would have required fifteen thousand dollars’ worth of human bones and muscles to have performed in a southern port.

I found that everything was done here with a scrupulous regard to economy, both in regard to men and things, time and strength. The maid servant, instead of spending at least a tenth part of her time in bringing and carrying water, as in Baltimore, had the pump at her elbow. The wood was dry, and snugly piled away for winter. Woodhouses, in-door pumps, sinks, drains, self-shutting gates, washing machines, pounding barrels, were all new things, and told me that I was among a thoughtful and sensible people. To the ship-repairing dock I went, and saw the same wise prudence. The carpenters struck where they aimed, and the calkers wasted no blows in idle flourishes of the mallet. I learned that men went from New Bedford to Baltimore, and bought old ships, and brought them here to repair, and made them better and more valuable than they ever were before. Men talked here of going whaling on a four years’ voyage with more coolness than sailors where I came from talked of going a four months’ voyage.

I now find that I could have landed in no part of the United States, where I should have found a more striking and gratifying contrast to the condition of the free people of color in Baltimore, than I found here in New Bedford. No colored man is really free in a slaveholding state. He wears the badge of bondage while nominally free, and is often subjected to hardships to which the slave is a stranger; but here in New Bedford, it was my good fortune to see a pretty near approach to freedom on the part of the colored people. I was taken all aback when Mr. Johnson—who lost no time in making me acquainted with the fact—told me that there was nothing in the constitution of Massachusetts to prevent a colored man from holding any office in the state. There, in New Bedford, the black man’s children—although anti-slavery was then far from popular—went to school side by side with the white children, and apparently without objection from any quarter.

To make me at home, Mr. Johnson assured me that no slaveholder could take a slave from New Bedford; that there were men there who would lay down their lives, before such an outrage could be perpetrated. The colored people themselves were of the best metal, and would fight for liberty to the death.

This text was taken from Chapter 22 of Frederick Douglass’ autobiography My Bondage and My Freedom, available at the website Lit2Go.

No comments:

Post a Comment