‘This Storm Has Broken People’: After Beryl, Some Consider Leaving

J. David Goodman

Tue, 16 July 2024

Michael McCormack, who works remotely in tech sales and, had a tree crash through his rental house during a storm in May, in Houston on July 15, 2024. (Meridith Kohut/The New York Times)

HOUSTON — Houston is no stranger to natural disasters, but living through two crippling power outages in two months has driven some in the city to consider what may be the ultimate evacuation plan: moving out.

The more powerful of the storms, Hurricane Beryl, devastated the power infrastructure over nearly the entire city. When it hit, thousands of people were already living in shelters and hotels, according to state officials, because they had been displaced by an earlier weather event, the spring thunderstorms that caused wind damage and flooding.

Driving around Houston, it can be hard to tell which of the storms that crashed through the city had mangled the highway billboards, torn out the fences or knocked down the trees still strewn along roadsides.

Everyone knows how long it took to get their power back from the first big storm — and when they lost it again. A second round of spoiled food. Of sweltering temperatures. Of emergency plans. In many cases, of repairs to homes that were damaged in the major May storm had yet to be finished when Beryl arrived as a Category 1 hurricane.

For some, it was too much.

“I’m just done, “ said Stephanie Fuqua, 52, who moved to Houston in 2015 and plans to leave in the fall.

Fuqua’s home had flooded during Hurricane Harvey in 2017. She shivered under blankets for three days when the state’s electrical grid failed during the winter of 2021. Then came the most recent storms, which left her sweltering without power.

“I’m tired of the trauma,” she said. When her lease is up in November, she said, she plans to move to a place where she has family, possibly Arkansas, Mississippi or South Carolina. “I love Houston. If it weren’t for the hurricanes and CenterPoint, I would stay here,” she said.

More than 2.2 million customers of the local utility, CenterPoint Energy, were without power at the peak of the outages last week. As of late Monday, around 135,000 were still in the dark.

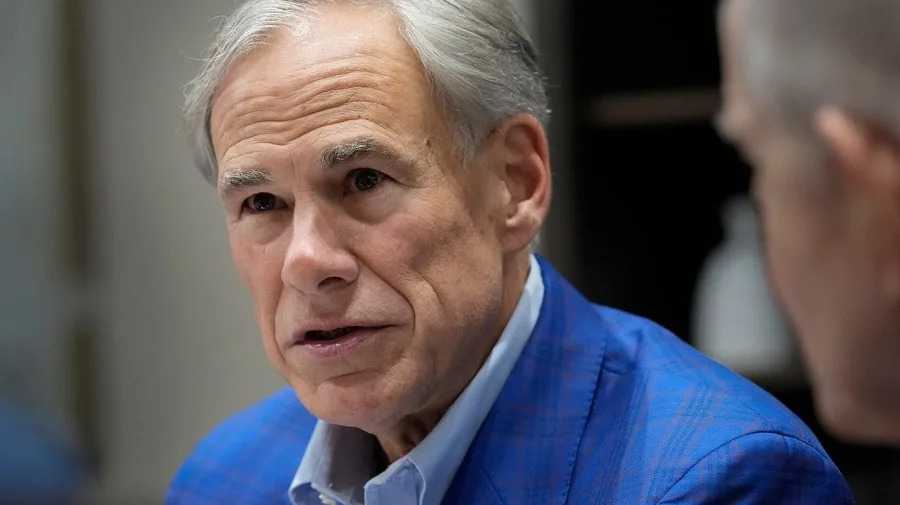

Gov. Greg Abbott, who was on an economic development mission in Asia for most of last week, blamed the utility for the widespread power failures, saying on Monday that it had “dropped the ball.” He threatened to take action himself if the company did not provide clear plans for improvement.

The back-to-back blows left Houston, which prides itself on its resilience and optimism, unusually shaken and unsure of the future. Those who could afford them scrambled for generators, fearing what a storm even more powerful than Beryl, rated as a Category 1 when it made landfall, might do.

“Beryl was the weakest a hurricane could be. Why does it feel like Houston isn’t the same?” The Houston Chronicle asked in a headline.

“I think this storm has broken people,” said Lawrence Febo, 47, who works in the energy sector and was without power for six days in the hurricane after being in the dark for four days in the May storm. “It’s the energy capital of the world and we cannot electrify a couple of million people?”

Then there was the matter of trees falling onto houses during the two storms.

“It came through my kitchen, took out half my house,” said Michael McCormack, 32, describing the large pine tree that crashed down during the May thunderstorms.

McCormack, a remote worker in software sales, had moved to Houston a little more than a year earlier from Seattle, drawn by the “cost of living, friendly people and better weather.” He was out of power for eight days — one of around 1 million customers who lost power during that storm.

With his lights still out, he looked to move farther inland to Fort Worth, or even back to the Pacific Northwest. But the logistics were complicated, so he and his 3-year-old dog, Chevy, moved to another rental house in Houston, not far away.

Then Hurricane Beryl hit and he lost power again. For days.

“I had water streaming in through my attic. I’m like, not again,” he said. “When my lease is up here, I have to make a judgment call.”

Leslie Schover, 71, a psychologist, said she had been thinking about moving, but there was the matter of a destination. “I just think, ‘Where would I go?’” she said. “There are climate-change weather dangers everywhere. And if I tried to live closer to my son in New York, it’s very expensive.”

Climate migration is a global phenomenon, but Houston may be particularly vulnerable. The city has long attracted transplants from other parts of the country seeking job opportunities and lower living costs.

Those who have recently arrived may have less of what is sometimes called “place attachment” — essentially, the kind of connection people have to the area where they live — making them perhaps more open to departing after a natural disaster, experts in disaster response said.

A 2020 study of disasters in the United States going back nearly 100 years found that “severe disasters increase out-migration rates” in the years after.

“Areas that fail to protect local quality of life in the face of extreme events will suffer a ‘brain drain’ as people and jobs will migrate to relatively safer areas,” one of the authors of the study, Matthew Kahn, an economics professor at the University of Southern California, said in an email.

Even before the storms, Harris County, which includes Houston, had been experiencing net negative migration from other parts of the country: Since 2016, according to U.S. census data, more people have left Harris County for other counties than have moved in from elsewhere. That trend continued after 2017 when Hurricane Harvey flooded large areas of the city.

In 2023, for the first time, pollsters from the University of Houston’s Hobby School of Public Affairs asked about whether city residents had considered leaving. More than half of those surveyed said yes, with about one-fourth saying it was because of the weather.

“By far, Gen Z and millennials were the most concerned about weather,” said Renée Cross, the researcher and senior executive director of the Hobby School. (Those who identified themselves as Republicans were more likely to say crime was their major issue, she said.)

At the same time, the population of the counties around Houston has been growing. The situation has been largely mirrored in other parts of Texas. In Dallas, for example, the county that includes the city has seen more people leaving for other states than coming in from them. But the surrounding, suburban counties are booming.

How much of that is a result of how cities manage weather emergencies is unknown. Certainly, not everyone is ready to throw in their towels.

Jim McIngvale, a furniture store owner known as Mattress Mack who is perhaps Houston’s biggest and most ubiquitous booster, conceded that the image of the city had “taken a hit,” but he said it could be turned around.

“You stay the course,” McIngvale said, sitting in one of his furniture showrooms, an Astros hat on his head. A carved wood statue proclaiming “Houston Strong” stood nearby. “The people have a lot of fight in them,” he said.

Katie Mears, who leads U.S. response work for Episcopal Relief and Development, a nonprofit, said one important aspect of climate migration was the disparity in who can afford to engage in it.

“The narrative of overcoming is appealing, but some people do leave,” they said. “In these migration patterns, it’s usually the rich people who go first,” they said, as well as those who are younger and more highly educated.

At a cooling center and food distribution site in north Houston on Monday, no one talked about leaving town as they idled in a long line of cars waiting for water and some food to take home.

One woman, Nancy Evans, 96, said she could not imagine moving from her house in the Acres Homes neighborhood.

Perry Murry, 60, who grew up in Houston and has used a wheelchair since he was shot as a teenager, said he took refuge in his Toyota Camry during the recent outages, relying on its air-conditioning to stay cool. He did the same in the 2021 winter freeze, blasting the car’s heat. He said he would never leave.

“I’ve got Texans on my hat, Texans on my shirt, Texans on my feet,” he added, pointing to his apparel, emblazoned with the Houston Texans football logo. “This is my city.”

c.2024 The New York Times Company

Anger over Houston power outages after Beryl has repair crews facing threats from some residents

J. David Goodman

Tue, 16 July 2024

Michael McCormack, who works remotely in tech sales and, had a tree crash through his rental house during a storm in May, in Houston on July 15, 2024. (Meridith Kohut/The New York Times)

HOUSTON — Houston is no stranger to natural disasters, but living through two crippling power outages in two months has driven some in the city to consider what may be the ultimate evacuation plan: moving out.

The more powerful of the storms, Hurricane Beryl, devastated the power infrastructure over nearly the entire city. When it hit, thousands of people were already living in shelters and hotels, according to state officials, because they had been displaced by an earlier weather event, the spring thunderstorms that caused wind damage and flooding.

Driving around Houston, it can be hard to tell which of the storms that crashed through the city had mangled the highway billboards, torn out the fences or knocked down the trees still strewn along roadsides.

Everyone knows how long it took to get their power back from the first big storm — and when they lost it again. A second round of spoiled food. Of sweltering temperatures. Of emergency plans. In many cases, of repairs to homes that were damaged in the major May storm had yet to be finished when Beryl arrived as a Category 1 hurricane.

For some, it was too much.

“I’m just done, “ said Stephanie Fuqua, 52, who moved to Houston in 2015 and plans to leave in the fall.

Fuqua’s home had flooded during Hurricane Harvey in 2017. She shivered under blankets for three days when the state’s electrical grid failed during the winter of 2021. Then came the most recent storms, which left her sweltering without power.

“I’m tired of the trauma,” she said. When her lease is up in November, she said, she plans to move to a place where she has family, possibly Arkansas, Mississippi or South Carolina. “I love Houston. If it weren’t for the hurricanes and CenterPoint, I would stay here,” she said.

More than 2.2 million customers of the local utility, CenterPoint Energy, were without power at the peak of the outages last week. As of late Monday, around 135,000 were still in the dark.

Gov. Greg Abbott, who was on an economic development mission in Asia for most of last week, blamed the utility for the widespread power failures, saying on Monday that it had “dropped the ball.” He threatened to take action himself if the company did not provide clear plans for improvement.

The back-to-back blows left Houston, which prides itself on its resilience and optimism, unusually shaken and unsure of the future. Those who could afford them scrambled for generators, fearing what a storm even more powerful than Beryl, rated as a Category 1 when it made landfall, might do.

“Beryl was the weakest a hurricane could be. Why does it feel like Houston isn’t the same?” The Houston Chronicle asked in a headline.

“I think this storm has broken people,” said Lawrence Febo, 47, who works in the energy sector and was without power for six days in the hurricane after being in the dark for four days in the May storm. “It’s the energy capital of the world and we cannot electrify a couple of million people?”

Then there was the matter of trees falling onto houses during the two storms.

“It came through my kitchen, took out half my house,” said Michael McCormack, 32, describing the large pine tree that crashed down during the May thunderstorms.

McCormack, a remote worker in software sales, had moved to Houston a little more than a year earlier from Seattle, drawn by the “cost of living, friendly people and better weather.” He was out of power for eight days — one of around 1 million customers who lost power during that storm.

With his lights still out, he looked to move farther inland to Fort Worth, or even back to the Pacific Northwest. But the logistics were complicated, so he and his 3-year-old dog, Chevy, moved to another rental house in Houston, not far away.

Then Hurricane Beryl hit and he lost power again. For days.

“I had water streaming in through my attic. I’m like, not again,” he said. “When my lease is up here, I have to make a judgment call.”

Leslie Schover, 71, a psychologist, said she had been thinking about moving, but there was the matter of a destination. “I just think, ‘Where would I go?’” she said. “There are climate-change weather dangers everywhere. And if I tried to live closer to my son in New York, it’s very expensive.”

Climate migration is a global phenomenon, but Houston may be particularly vulnerable. The city has long attracted transplants from other parts of the country seeking job opportunities and lower living costs.

Those who have recently arrived may have less of what is sometimes called “place attachment” — essentially, the kind of connection people have to the area where they live — making them perhaps more open to departing after a natural disaster, experts in disaster response said.

A 2020 study of disasters in the United States going back nearly 100 years found that “severe disasters increase out-migration rates” in the years after.

“Areas that fail to protect local quality of life in the face of extreme events will suffer a ‘brain drain’ as people and jobs will migrate to relatively safer areas,” one of the authors of the study, Matthew Kahn, an economics professor at the University of Southern California, said in an email.

Even before the storms, Harris County, which includes Houston, had been experiencing net negative migration from other parts of the country: Since 2016, according to U.S. census data, more people have left Harris County for other counties than have moved in from elsewhere. That trend continued after 2017 when Hurricane Harvey flooded large areas of the city.

In 2023, for the first time, pollsters from the University of Houston’s Hobby School of Public Affairs asked about whether city residents had considered leaving. More than half of those surveyed said yes, with about one-fourth saying it was because of the weather.

“By far, Gen Z and millennials were the most concerned about weather,” said Renée Cross, the researcher and senior executive director of the Hobby School. (Those who identified themselves as Republicans were more likely to say crime was their major issue, she said.)

At the same time, the population of the counties around Houston has been growing. The situation has been largely mirrored in other parts of Texas. In Dallas, for example, the county that includes the city has seen more people leaving for other states than coming in from them. But the surrounding, suburban counties are booming.

How much of that is a result of how cities manage weather emergencies is unknown. Certainly, not everyone is ready to throw in their towels.

Jim McIngvale, a furniture store owner known as Mattress Mack who is perhaps Houston’s biggest and most ubiquitous booster, conceded that the image of the city had “taken a hit,” but he said it could be turned around.

“You stay the course,” McIngvale said, sitting in one of his furniture showrooms, an Astros hat on his head. A carved wood statue proclaiming “Houston Strong” stood nearby. “The people have a lot of fight in them,” he said.

Katie Mears, who leads U.S. response work for Episcopal Relief and Development, a nonprofit, said one important aspect of climate migration was the disparity in who can afford to engage in it.

“The narrative of overcoming is appealing, but some people do leave,” they said. “In these migration patterns, it’s usually the rich people who go first,” they said, as well as those who are younger and more highly educated.

At a cooling center and food distribution site in north Houston on Monday, no one talked about leaving town as they idled in a long line of cars waiting for water and some food to take home.

One woman, Nancy Evans, 96, said she could not imagine moving from her house in the Acres Homes neighborhood.

Perry Murry, 60, who grew up in Houston and has used a wheelchair since he was shot as a teenager, said he took refuge in his Toyota Camry during the recent outages, relying on its air-conditioning to stay cool. He did the same in the 2021 winter freeze, blasting the car’s heat. He said he would never leave.

“I’ve got Texans on my hat, Texans on my shirt, Texans on my feet,” he added, pointing to his apparel, emblazoned with the Houston Texans football logo. “This is my city.”

c.2024 The New York Times Company

Anger over Houston power outages after Beryl has repair crews facing threats from some residents

JUAN A. LOZANO

Tue, 16 July 2024

FILE - Utility crews work to restore electricity in Houston, Thursday, July 11, 2024. Houston’s prolonged outages following Hurricane Beryl has some fed-up and frustrated residents taking out their anger on repair workers who are trying to restore power across the city. (AP Photo/Lekan Oyekanmi, File)

HOUSTON (AP) — Drawn guns. Thrown rocks. Threatening messages. Houston’s prolonged outages following Hurricane Beryl has some fed-up and frustrated residents taking out their anger on repair workers who are trying to restore power across the city.

The threats and confrontations have prompted police escorts, charges in at least two cases, and pleas from authorities and local officials to leave the linemen alone so they can work.

Beryl knocked out power to nearly 3 million people in Texas — with most of those in the Houston area — after making landfall July 8. The Category 1 storm unleashed heavy rain and winds that uprooted trees and damaged homes and businesses along the Texas Coast and parts of Southeast Texas. State authorities have reported 18 deaths from Beryl. In the Houston area, some have been due to heat exposure following the loss of power, according to the medical examiner’s office in Harris County.

As of Tuesday, crews were still working to restore power to some residents.

“Linemen are our friends and are doing their job. Do not threaten them. I understand you’re angry and mad and frustrated, but let’s get through this together,” Mayor John Whitmire said during a news conference on Monday.

Houston police have investigated at least five cases involving threats made to workers and other employees, whether in person or online.

In one of these cases, police arrested Anthony Leonard, 38, charging him with aggravated assault with a deadly weapon. Authorities allege Leonard on Saturday threw rocks and pointed a gun at a group of CenterPoint Energy workers who were at a staging area.

Leonard remained jailed Tuesday. His attorney did not immediately return a call seeking comment.

CenterPoint CEO Jason Wells said over 100 line workers had to be evacuated from the staging area on Saturday. He said such threats are counterproductive as crews have to be moved to safer areas, delaying their work.

“So many of our fellow Houstonians have addressed this situation with patience and grace. And I want to thank them. But unfortunately, there have been instances where either acts of violence have been threatened or actually committed against our crews that are working this vital restoration. This is unacceptable. The safety of our crews is paramount,” Wells said.

KPRC reported that a charge of making a terroristic threat has been filed against a woman from the Houston suburb of Baytown. The Texas Department of Public Safety alleges the woman made multiple online threats of murder, assault and deadly conduct against employees, including Wells, at CenterPoint’s headquarters in downtown Houston. The woman has not been arrested.

Chief Deputy Mike Lee with the Harris County Sheriff’s Office said his agency has investigated a break-in of a CenterPoint vehicle and three cases where residents refused to let linemen enter their properties.

Ed Allen, business manager for the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local Union No. 66, which represents workers at CenterPoint, said in 42 years in this industry, he’s never seen a response like this where workers are being threatened.

Allen said he spoke to one crew that said while they were working in a suburban Houston neighborhood, several men stood across the street from them and held an assault type rifle in a menacing way.

“It is very disheartening to see the community that I’ve worked in and that I’ve dedicated my life to provide electricity to act the way they have during this event,” Allen said.

Crews on Tuesday told Allen they haven’t received any new threats.

“I hope it’s gotten better out there. Part of that I think has a lot to do with the fact that regardless of what anybody thinks, the restoration effort has gone really well,” Allen said.

As of late Tuesday afternoon, CenterPoint reported that less than 82,000 customers remained without power.

On Tuesday, Gov. Greg Abbott sent a letter to CenterPoint demanding information from the company, including what actions it will take to reduce or eliminate power outages during future storms and how it will improve communication with its customers before, during and after a weather event.

“Texans must be able to rely on their energy providers to keep the power flowing, even during hurricane season. It is your responsibility to properly prepare for these foreseen incidents and work tirelessly to restore power as quickly as possible when it is lost. Anything less is unacceptable,” Abbott wrote.

In a statement, CenterPoint said it's addressing Abbott's request and that its work with officials and community leaders to increase the resiliency of the electric grid is essential in "creating and sustaining an environment in Texas where people want to live and build their businesses.”

Harris County Commissioner Adrian Garcia said the threats to CenterPoint workers and out-of-town crews only makes “it harder and longer to get your lights back on.”

“These folks are just here trying to help. Let them do their work and help us and tomorrow will be a better day,” Garcia said.

___

Follow Juan A. Lozano on Twitter: https://twitter.com/juanlozano70

Thousands in Houston still without power amid brutal heatwave after Beryl

Erum Salam

Mon, 15 July 2024

THE GUARDIAN

A family sits on their front porch as they get some air while their home is without power in Houston, Texas, on 12 July 2024.Photograph: Brandon Bell/Getty Images

Power outages persist in Houston, Texas, after Hurricane Beryl tore through the area last week leavings hundreds of thousands of residents without electricity in the middle of a brutal heatwave.

Nearly 300,000 customers have now gone almost a week without electricity and air conditioning during excessive heat where temperatures are reaching 94F (34C).

CenterPoint Energy, the region’s primary utility company, has been slammed by residents, as well as city and state officials, for what many have called poor communication about a timeline for power restoration and a lack of proper planning.

Initially, more than 2.2 million Houstonians had found themselves without power in the immediate aftermath of Beryl, igniting a crisis in the city that led to at least three heat-related deaths, hospitalizations and the forced displacement of people from their homes to find cooler locations.

CenterPoint said on Monday it restored power to more than 2 million customers and expects to approximately 98% restoration by the end of Wednesday, as lineman crews work “around-the-clock and in difficult conditions” to turn the lights and a/c back on.

The company blamed fallen trees and branches from the severe weather for damaging infrastructure and customer-owned equipment, which delivers power to much of the city and surrounding areas.

But the Texas governor, Greg Abbott, said in a statement that CenterPoint has “repeatedly failed to deliver power to its customers” and has given the energy company until the end of the month to provide “specific actions to address power outages and reduce the possibility that power will be lost during a severe weather event”.

CenterPoint did not respond to a request for comment.

Abbott, who was in Asia on an economic development trip during the crisis in his state, has also directed the Public Utility Commission of Texas (PUC) conduct an investigation into the situation.

“It is unacceptable that millions of Texans in the Greater Houston area have been (or were) left without electricity for multiple days. It is imperative we investigate how and why some Texas utilities were unable to restore power for days following a Category 1 Hurricane,” Abbott wrote in a letter on Sunday to PUC chairman Thomas Gleeson.

Cassandra Hollingsworth, who lives in the Spring area of northern Houston and is disabled, told the Guardian that CenterPoint has been “wholly unprepared, which is unacceptable as the largest energy provider in the Houston area”.

“Many elderly and disabled people are suffering and unable to care for themselves in these extreme temperatures, and as far as I’m concerned, anyone who perishes due to the prolonged outages is on CenterPoint,” Hollingsworth, 42, said. “There has to be a stronger system and/or a more urgent response, particularly when most summer days in Houston either are, or feel like, triple digit temperatures.

4 things to know about the Houston power crisis

A family sits on their front porch as they get some air while their home is without power in Houston, Texas, on 12 July 2024.Photograph: Brandon Bell/Getty Images

Power outages persist in Houston, Texas, after Hurricane Beryl tore through the area last week leavings hundreds of thousands of residents without electricity in the middle of a brutal heatwave.

Nearly 300,000 customers have now gone almost a week without electricity and air conditioning during excessive heat where temperatures are reaching 94F (34C).

CenterPoint Energy, the region’s primary utility company, has been slammed by residents, as well as city and state officials, for what many have called poor communication about a timeline for power restoration and a lack of proper planning.

Initially, more than 2.2 million Houstonians had found themselves without power in the immediate aftermath of Beryl, igniting a crisis in the city that led to at least three heat-related deaths, hospitalizations and the forced displacement of people from their homes to find cooler locations.

CenterPoint said on Monday it restored power to more than 2 million customers and expects to approximately 98% restoration by the end of Wednesday, as lineman crews work “around-the-clock and in difficult conditions” to turn the lights and a/c back on.

The company blamed fallen trees and branches from the severe weather for damaging infrastructure and customer-owned equipment, which delivers power to much of the city and surrounding areas.

But the Texas governor, Greg Abbott, said in a statement that CenterPoint has “repeatedly failed to deliver power to its customers” and has given the energy company until the end of the month to provide “specific actions to address power outages and reduce the possibility that power will be lost during a severe weather event”.

CenterPoint did not respond to a request for comment.

Abbott, who was in Asia on an economic development trip during the crisis in his state, has also directed the Public Utility Commission of Texas (PUC) conduct an investigation into the situation.

“It is unacceptable that millions of Texans in the Greater Houston area have been (or were) left without electricity for multiple days. It is imperative we investigate how and why some Texas utilities were unable to restore power for days following a Category 1 Hurricane,” Abbott wrote in a letter on Sunday to PUC chairman Thomas Gleeson.

Cassandra Hollingsworth, who lives in the Spring area of northern Houston and is disabled, told the Guardian that CenterPoint has been “wholly unprepared, which is unacceptable as the largest energy provider in the Houston area”.

“Many elderly and disabled people are suffering and unable to care for themselves in these extreme temperatures, and as far as I’m concerned, anyone who perishes due to the prolonged outages is on CenterPoint,” Hollingsworth, 42, said. “There has to be a stronger system and/or a more urgent response, particularly when most summer days in Houston either are, or feel like, triple digit temperatures.

4 things to know about the Houston power crisis

Saul Elbein

Tue, 16 July 2024

More than a quarter million people in and around Houston remained without power as of Monday after Hurricane Beryl hit the city last week — a crisis that has sparked political pressure from both sides of the aisle and drawn new attention to Texas’s troubled grid.

Gov. Greg Abbott (R) is demanding answers from the state’s biggest power utility about what went wrong in the storm, which led to blackouts for nearly 3 million people across Southeast Texas for days. He has given CenterPoint until the end of the month to offer an explanation amid a broad lack of response from the utility.

“The communications component of CenterPoint is unacceptable,” Abbott told reporters Sunday. “Corrections are coming, whether they like it or not.”

Democratic lawmakers have called for scrutiny of the utility as well. Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee (D-Texas), sent a letter to the Department of Justice on Friday asking for a federal investigation of CenterPoint, which she argued has left hundreds of thousands of Houstonians in the dark after several weather disasters this year.

The outages in Beryl’s wake — and the political response — also represented something bigger: the return of the Texas grid as a political live wire, as climate change driven by the burning of fossil fuels turns the weather increasingly dangerous.

Here’s what you need to know about the outages, their political fallout and why Houston is at the forefront of America’s climate crisis.

How bad is the situation in Houston?

It has been a grim illustration of the tendency of crises to compound.

Houston’s brutal summer saw heat indexes — the metric of how hot it feels in the shade — reach above 104 on Monday, with the penetrating Texas sun pushing that subjective temperature up by an additional 10-15 degrees.

That heat is bearing down on a population with a high degree of chronic medical problems, medical debt and food insecurity; limited worker protections; and — for hundreds of thousands — still no electricity.

While about 90 percent of Harris County residents who lost power since last Monday have since had their power switched back on, a little under a quarter million households remain without power, according to CenterPoint — or, in human terms, the equivalent of the entire city of Sacramento, Calif.

Lack of electricity means no air conditioning, which is the chief technical innovation that drove Houston’s late-20th century boom and that makes the city habitable for residents who live there now.

Without air conditioning, residents slept in cars or drove around the region trying to find a hotel with vacancies — provided that they could afford a hotel, or had a car. About 7 percent of Harris County residents, or 334,000 people, don’t have access to an automobile.

That means emergency rooms are seeing twice as many hospital admissions as usual this year, and three times as many people as would typically be suffering from heat-related illness, according to The Associated Press.

Then there is food: No power also means no refrigeration, and — for those with electric appliances, or even many gas ones — no way to cook.

What caused the outages?

In the immediate sense, the reason millions of Southeast Texas residents went days without power is that Hurricane Beryl slammed into the Houston area last week, maintaining Category I strength for most of its passage over the city and doing at least $2.5 billion in damage from its winds alone.

With gusts of more than 80 mph, Beryl — which later weakened to a tropical storm — knocked down 10 major transmission lines into Houston, as well as an untold number of utility poles.

“Beryl was mostly a wires issue,” Tom Overbye of Texas A&M University’s Smart Grid Center told Community Impact. “What I suspect happened is you have trees falling on distribution lines, and you also have higher wind knocking over some transmission towers and distribution towers as well.”

To make matters worse, Beryl arrived with an element of surprise: Projections showed landfall much farther south, but the storm took a hard right turn last Monday and ran up the coast before slamming its more powerful “dirty side” into Houston — a city already reeling from major storms in May and June, each of which left hundreds of thousands without power.

For its part, CenterPoint has pointed to the storm’s surprising and protracted strength. “This hurricane moved over the entirety of our system, it didn’t brush by a portion of it,” CEO Jason Wells told The Houston Chronicle.

“We had contributing factors, weak trees over the past growing seasons. So it doesn’t really matter the distinction from a Category 1 or a Category 2. This was a hurricane that hit all of the greater Houston area, and we had to respond to that.”

In other messaging, CenterPoint noted that downed power lines aren’t the only reason for failures: The storm also damaged many households’ “weatherheads,” the port where electric lines enter the house, the company has observed.

But for many Houston residents, outside experts and state officials, pointing at the ferocity of Beryl itself — or the cumulative damage of the summer’s storms in general — provides only a partial answer.

“A cat 1 hurricane shouldn’t knock out your power system,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology hurricane researcher Kerry Emanuel told InsideClimate News. “I think you’ve got a problem with the power company, frankly.”

Why are residents, lawmakers criticizing CenterPoint?

In his interview with the Chronicle, Wells said he was “proud” of CenterPoint’s investments before the storm, and its quick work after.

The company’s investments in high-tension lines “operated as designed. We built our transmission structures to withstand extreme winds, and we had minimal damage to the transmission system,” he said.

Bringing back power to more than 1 million people “within effectively 48 hours of the storm’s passing is faster than what many of our peers have seen in the past 10 named storms,” he added.

But a number of area residents and Texas lawmakers have criticized CenterPoint’s management of power lines prior to the storm, and the utility’s communication strategy in its aftermath.

Immediately after the storm, the Houston Chronicle’s editorial board published a blistering editorial criticizing the company’s short- and long-term preparation. One key issue raised by the board was the utility’s lack of transparency in whether it had proactively cleared trees — which in storms can become lethal to local power supplies — from power easements, maintenance activity some Houstonians told KHOU they had never seen.

Measuring by dollars per customer, CenterPoint’s spending on clearing up trees was second-to-last among the four major Houston-area utilities, according to KHOU. The company contends that its spending on tree trimming went up nearly a third between 2022 and 2023.

While the tree issue is complex, the Chronicle board argued, other failures were less forgivable — like the fact that the utility’s outage tracker had been down since the May thunderstorms, or that the company did not call in out-of-state linemen needed for repair until after the storm had passed, rather than bringing them in proactively.

“By now, Houstonians have set a pretty low bar for CenterPoint Energy,” the board wrote. “What we do expect from our power utility is transparency. Preparation. Resiliency.”

“It appears that CenterPoint failed on all counts.”

Residents waiting for their power to get turned on have reported long hold times or an inability to get in touch with CenterPoint representatives, who have announced plans to get the number of outages down to about 45,000 households by the end of the day Wednesday.

Many who have gotten a response haven’t liked what they heard. Houston residents posted to the social platform X apparent screen grabs of CenterPoint messages saying they would be without power until this Friday, July 19.

Much of the anger residents directed toward CenterPoint in the storm’s wake was rooted in Houstonians’ past experiences with the utility as well — in particular Hurricane Ike in 2008, when more than 2 million spent nearly two weeks without power.

“I remember driving around to charge a flip phone and hearing Mayor White on [Houston Public Radio] essentially begging CenterPoint to hurry,” Allyn West of the Environmental Defense Fund wrote on X. “How has nothing changed in 16 years?”

In a later post, looking at two other trends since Ike — the inflation-driven one-third drop in the value of the dollar, and the 20 percent rise in days over 90 degrees — West concluded things, in fact, had changed in Houston: “They’ve gotten worse and more expensive.”

In a comment to The Hill, CenterPoint’s media relations team said the company was was “committed to working together with state and local government, regulators, and community leaders both to help the Greater Houston area recover from Hurricane Beryl and to improve for the future.”

“We are also committed to doing a thorough review of our response, supporting any external inquiries, and continuing to serve our customers and our communities, especially when they need us most.”

Other CenterPoint messaging has garnered further criticism. On-hold messages encouraged callers to buy generators from a partner company.

In her letter to the Department of Justice, Jackson Lee, a former Houston mayoral candidate, offered a list of company failures reported in local media, including the generator hold message, reports of workers “sitting idly in fully equipped trucks and not responding to calls” and pervasive “inconsistencies and inaccuracies” faced by customers seeking updates of when their power would be back on. “This is simply inexcusable for a company that has a fiduciary duty to its customers.”

She asked federal officials to investigate the company’s “inability to appropriately and effectively provide life-saving utility services its customers rely on.”

Jackson Lee warned that “without urgent action, and the threat of additional storms ahead, Texas could be on the verge of … deadly and costly mass casualties” driven by the combination of power failures and extreme heat.

Abbott and Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick (R), who have broadly opposed federal oversight, called on the state’s own Public Utilities Commission (PUC) to look into whether CenterPoint was “penny-pinching and cutting corners.”

In an meeting of the PUC, Chair Thomas Gleeson (R) suggested CenterPoint’s great failure had been its outreach.

“The infrastructure is gonna break; things are gonna happen,” Gleeson told CenterPoint officials. “But if people feel they’re being effectively communicated with, it makes it a lot easier to go through it. And so I’d say, get out in the community and go talk to your customers.”

For his part, Patrick had a harder series of questions. Over the weekend, he announced plans for the state Senate, which he presides over, to grill CenterPoint officials beginning in August. When that happens, Patrick wrote on X, officials would have to answer questions such as “Did they cut corners before the storm?”, “Are they cutting corners now?” and “are Houston and surrounding areas still IMPORTANT to CenterPoint?”

While Texans understand the unusual impacts of Beryl, Patrick wrote, “people have a right to be extremely frustrated with CenterPoint.”

Across Southeast Texas, he added, “people are suffering through terribly oppressive heat, a lack of food and gasoline availability, debris everywhere, and much more. The poor and most vulnerable are suffering the most.”

What are experts and officials proposing to keep this from happening again?

Abbott is demanding CenterPoint tell him what it can do to prevent future crises by the end of the month — and he has said if the utility doesn’t come up with good answers, he will do so himself. One solution he has floated is breaking the company up.

“It’s time to reevaluate whether or not CenterPoint should have such a large territory,” he said.

Some experts, meanwhile, are calling for infrastructure reform. Local meteorologists at Space City Weather urged the state and city to consider the sort of solutions they say “should have” been implemented after Ike: “concrete poles, underground lines, microgrids, and other ideas.”

These options are common in Northern cities that deal with snowstorms, such as Buffalo, as KHOU reported. But they are more logistically difficult in Houston, where the ground is swampy and increasingly flood-prone — and spiderwebbed with an often-uncharted mix of legacy gas pipes and fiber optic cables.

As The Texas Monthly reported last year, in 2021, PG&E proposed burying its overhead transmission lines, which had sparked the deadly Camp Fire — at a cost of $2.5 million per mile.

Scale that over the CenterPoint network, and the cost would amount to $132 billion — more than 20 times the company’s 2023 annual profits. A more modest proposal reviewed by the Chronicle would have cost $29 billion in 2009, or about $50 billion today.

Burying cables is expensive because they have to be carefully insulated to keep power from surging through the ground — which isn’t a risk for airborne cables. “The earth is a conductor, and you can’t have the electricity going into the earth,” Texas A&M electrical engineering professor B. Don Russell told Click2Houston.

The cost of burying main transmission lines would be “exponentially” higher than doing so with the smaller-capacity neighborhood lines that supply homes, Russell added — costs he said the utility would likely pass on to consumers.

A sense of urgency hovers over the debate. Beryl was a stunningly early major storm in a season forecasters expect to be at or near-record levels — and it was only a Category 1 storm, though one uniquely placed to do maximum damage.

As Houstonia magazine reported, in a Category 2 storm, like Ike, the power might be off for a couple of weeks; a Category 3 storm, like 1983’s Alicia, could leave residents in the dark even longer. A Category 4 like the fearsome 1900 storm that wrecked Galveston, then Texas’s biggest city, would lead to “power outages [that] are expected to be complete and [that] could take months to restore.”

And climate change, driven largely by burning the products whose manufacture built Houston — fossil fuels — means those storms are only getting worse, and more frequent, in tandem with development advancing over the prairies and wetlands that would otherwise absorb their water and blunt their winds.

Beginning to reverse the process of neighborhood construction that has filled the floodplain with houses, University of Chicago historian Jonathan Levy wrote after 2017’s Hurricane Harvey, would cost an estimated $27 billion and require the city to appropriate and clear 10,000 structures currently in the 100-year floodplain.

A Houston native who grew up in one of the neighborhoods that would be cleared for flood-absorbing green space under such a plan, Levy argued that Houston was emerging as the capital of a broader American climate paradox: The city, he observed, is both made by, and being unmade by, the impacts of fossil fuels.

Finding the politics necessary to solve these problems “would seem impossible,” Levy wrote. “But on the planetary scale, much more dramatic and improbable efforts than this will likely be required.”

“If you have no politics for what to do with Houston, that is, then you have no politics for what to do about global warming,” he added.

No comments:

Post a Comment