Is Zohran Mamdani a ‘Crazed Socialist?’ — A Closer Look

Since democratic socialist Zohran Mamdani won a decisive victory over Andrew Cuomo in New York City’s June 24th Democratic mayoral primary, leading establishment personalities in the political and economic sphere have attacked him with a combination of Islamophobia, anti-immigrant racism, smears of anti-semitism and predictions of economic apocalypse should Mamdani win the mayoral general election in November. New York’s billionaire businessmen have had meetings strategizing about ways to derail Mamdani’s seemingly likely election victory in November. These business elites are frightened by Mamdani’s proposals to significantly raise NYC’s minimum wage, open government run grocery stores, and raise taxes on millionaires and businesses in order to find free childcare, social housing, free bus service and free tuition at the city’s public colleges.

The red baiting has been particularly heavy. Fox Business Network journalist Charles Gasparino, writing in the New York Post, called Mamdani a “crazed socialist.” President Trump called him a “100 percent Communist lunatic. In a hysterical June 30th Wall Street Journal Op-Ed, billionaire NYC supermarket mogul John Catsimatidis compared Mamdani to Fidel Castro and Hugo Chavez, predicting that were he to be elected and implement his proposal for government run supermarkets in the city, the result would be “poverty, rationing and hunger…[it] would collapse our food supply, kill private industry, and drag us down a path toward the bread lines of the old Soviet Union.”

Other establishment commentators have been somewhat calmer but offered no less dire predictions about the consequences of a potential Mamdani mayoralty. For example, Lucy Biggers, social media editor at The Free Press, wrote a June 30th column, criticizing Trump’s crude red-baiting of Mamdani as too harsh; she nonetheless argued that his democratic socialist policies would “literally ruin civilization.” Larry Summers, former treasury secretary under Bill Clinton, asserted that Mamdani’s democratic socialism ideology has “a history of perpetuating poverty and poor social service”; he predicted Mamdani’s election would cause a massive capital flight–entrepreneurial talent as well as money–out of the city toward the Republican states of Florida and Texas. Similarly New York’s business friendly Democratic governor Kathy Hochul attacked Mamdani’s proposals for increasing taxes on NYCs’ wealthy and businesses as likely to cause significant capital flight.

Are any of the commentators quoted above correct? Is Mamdani a “crazed socialist?” Will the inevitable result of the implementation of his policies be: “perpetuating poverty and poor social service?”

My answer to each of these questions is: no. I will point out that Mamdani’s policies are not particularly extreme and are actually in line with historical and contemporary models showing that, under the right conditions, they have the potential to significantly strengthen a population’s overall well being and can even contribute to strengthening a capitalist economy. However, the policies do require at least the toleration of the capitalist class: in some countries historically, various cultural factors–including the power of organized labor and established social democratic parties–have compelled the capitalist class to accept economic policies similar to Mamdani’s. However, in a country like the United States–where capital is more dominant over labor than almost anywhere else in the western world–the capitalist class is in a relatively easy position to sabotage the implementation of Mamdani’s agenda were he to become mayor.

Government Run Grocery Stores

Take the Mamdani’s proposal for municipally owned grocery stores, one that seems to have rankled his right wing critics more than any of his other proposals. To dispose of this idea, Biggers wrote in her Free Press column: “just spend time at the DMV and tell me if you want a government run grocery store, as Mamdani is proposing”, implying that such a grocery store would have long lines and poor customer service.

In a commentary for MSNBC’s website, democratic socialist publicist Ben Burgis pointed out that Mamdanis’s proposal for government run grocery stores matches the principles behind government run commissaries on military bases and state government run liquor stores –not the DMV. There are 17 states in the country with public monopolies on liquor sales. Burgis notes that New Hampshire’s public liquor stores are renowned throughout New England for their plentiful and cheap supply of many brands of beer and spirits.

To be clear, as Burgis points out, Mamdani’s idea for a government run grocery store is actually not that extreme. All he has called for is a pilot project whereby one municipally owned grocery store is opened in each of NYC’s five boroughs. This pilot project is designed to address a market failure: the existence of food deserts in some of the city’s neighborhoods: because of lack of profitability, grocery stores have neglected to open–or opened only to a limited extent–in some of the city’s poorer, predominantly black and brown communities, depriving residents of access to fresh meats and produce. In poorer NYC neighborhoods, 30 percent of residents have been classified as “food insecure,” meaning they have limited or uncertain access to nutritious food.

In recent years, similar food deserts in rural areas, deep in the heart of MAGA country, caused the municipalities of Erie, Kansas and Baldwin Florida to open publicly run grocery stores. In the past year, after multiple years in operation and the accumulation of financial difficulties, the Erie store was leased to a private company and the Baldwin store was closed entirely (leaving Baldwin as a food desert). Perhaps the most successful example of a municipally owned grocery store is in the tiny town of St. Paul, Kansas, which the Wall Street Journal reported in 2023 had been run successfully for 16 years, and, according to one report, secured a 3 percent annual profit margin, better than average for rural grocery stores.

Housing

In a TikTok video, the above mentioned right wing commentator Lucy Biggers suggested that the average young Mamdani voter is drawn to what are, in her telling, his promises of “free food, free college, free apartments,” because they have immature brain structure (their “frontal lobe is not fully developed.”). In contrast, I believe the real answer for Mamdani’s support is embodied in a recent Wall Street Journal headline: “New York’s Housing Crisis Is So Bad That a Socialist is Poised to Become Mayor.” The Journal reported that the average monthly rent for a 2 bedroom apartment in the city was $5,560, up 17.5 percent over the previous year. In October 2023, the Community Service Society of New York reported that more than a third of NYC renters were paying half their income on rent.

Mamdani’s program revolves around a rent freeze for NYC apartments subjected to rent stabilization regulations (about half of the city’s total apartments) along with significantly increased spending on public housing, reform of zoning laws and the borrowing of $70 billion to subsidize affordable housing and social housing construction. Critics have suggested that his plans may be at least partially sabotaged by the fact that his housing spending plans exceed New York City’s debit limit by $30 billion; that debt limit, under the New York state constitution, is enforced by the New York state government against NYC and all other state municipalities. The chance seems faint that governor Hochul would approve of any significant increases to the NYC debt limit–she has also expressed hostility towards Mamdani’s call for tax increases in NYC which she is legally empowered to veto if she wishes.

Nonetheless it is undeniable that democratic socialist housing models around the world show that if Mamdani can somehow, under very difficult circumstances, cobble together the right amount of revenue and right mix of regulations, he can succeed in providing widespread affordable housing for NYC residents. There are prominent examples around the world of governments providing plentiful, affordable, safe, clean, architecturally attractive and environmentally sustainable housing for working and middle class people. Finland and Norway are just two examples of successful public housing provision around the world; Vienna, the capital of Austria, is perhaps the prominent example in the world of successful public housing provision. In 2024, The Economist named Vienna as the world’s most liveable city. 43 percent of its housing units are public housing: half of these are owned by the local government and the other half are social housing owned by limited profit organizations and heavily regulated by that government. Mamdani has cited the Vienna model as an inspiration to his own housing plan.

In the United States, public housing has the stereotype of being crime infested hellholes. In fact, as The Atlantic reported in 2015, cities like Austin, Texas; Portland, Oregon; and St. Paul Minnesota have developed successful government run housing models. In NYC, the most successful examples of public housing are rooted in the Mitchell-Lama Act passed by the New York state legislature in 1955. Mitchell-Lama measures created a form of social housing in NYC: substantial government subsidies for building mortgages as well as for residents’ apartment down payments and monthly rents or maintenance fees in apartment buildings and co-ops. The result was the creation of safe, affordable, relatively efficiently operated apartments for a small number of working and middle class New Yorkers. Jonathan Tarleton–editor of the NYC newspaper The Indypendent–in his 2025 book Homes for Living: The Fight for Social Housing and a New American Commons–describes the historical success of social housing in NYC.

Mamdani’s Precedents

There are precedents for successful free market economies following policy along lines posed by Mamdani, in some cases engaging in government economic intervention far more extensive that what he is proposing. There are many worldwide examples of successful government programs that have strengthened the human capital of capitalist economies and produced better quality of life indicators than that achieved in the arch-capitalist United States. This essay does not have the space to list them all but–like the Vienna housing model cited above–here are a few more examples cited below.

In his 2023 book Crack-Up Capitalism, Quinn Slobodian references the 1978 meeting of the worldwide association of pro-free market academics and business persons, the Mont Pelerin Society (MPS), in Hong Kong. As they met, leading MPS member Milton Friedman also filmed the first episode of his PBS series Free to Choose in Hong Kong, celebrating the city (then a British colony) as a prime example of free market success with worldwide status as a financial and manufacturing powerhouse. However, Slobodian notes, MPS members discovered something disconcerting while they met in the city: a third of its residents resided in public housing; there was even rent control, something particularly anathema to them. Public housing in the city was significantly expanded after riots among the city’s poor and working class in 1967–the city’s ruling class sought to ensure greater social stability by granting ordinary people concessions.

In the same region of Hong Kong sits Singapore, a paternalistic right wing dictatorship that has been, over the decades, a world leader, in terms of finance and manufacturing, featuring extensive governmental intervention in its economic life. Slobodian notes that Friedman in 1980 blustered that Singapore had become an economic powerhouse “despite extensive interventions of government.” However, Slobodian writes, the reality is that government economic intervention was decisive in Singapore’s economic success:

“…The government built industrial estates and added hundreds of acres of new land to its coastline through massive land reclamation projects. Many of its biggest companies were owned by the state, and huge sovereign wealth funds invested Singaporean savings domestically and globally.”

In addition, nearly 80 percent of Singaporean citizens today live in government run housing–the situation is different for the third of Singapore’s residents who are foreign migrant workers and thus are not entitled to government housing, much less any legal or citizenship rights.

Then there are examples of government economic intervention in ways that strengthen a country’s national economic development as well as strengthen its human capital through government controlled health care.

Take some of the most successful economies in the world: the Nordic countries (Finland, Sweden and Norway). The economic interventions by governments of these three countries make Zohran Mamdani’s proposal to launch a pilot project of a few government run grocery stores in NYC look very puny in comparison. All three Nordic countries have dozens of state owned enterprises operating successfully at the heart of their economies. There are other worldwide examples, like CODELCO, the largest copper company in the world, a state owned enterprise based in Chile (where copper is the largest export), a country which has often been cited by neoliberals as a successful third world model of free market economic development. CODELCO was created under the Pinochet dictatorship in 1976 after the government which Pinochet overthrew, that of Salvador Allende, nationalized Chilean copper resources in 1971.

As for health care, that is where Canada and almost every nation in Western Europe outperforms the US. Of course, Mamdani as a candidate for NYC mayor only marginally addresses health care in his platform and would have no real power as mayor to implement any substantial health care measure. However, Mamdani is a strong supporter of Medicare for All and the latter is usually included as a major part of democratic socialist policy agendas, those which Larry Summers alleged to be guilty of “perpetuating poverty and poor social service.” It is also worth citing something that Dr. Mehmet Oz stated in May in an interview with Fox Business host Maria Bartiromo:

“We spend twice as much as any other developed country per person on health care–twice as much! And yet the quality of the care we’re getting continues to decline. When I was in medical school, I saw a life expectancy of Americans pretty much equal to Europeans; now we’re five years behind. The number three cause of death in America is a medical error and yet, we’re paying a lot of money to experience results that don’t match that kind of investment.”

Capital Flight

There will be innumerable hindrances facing Mamdani should he win in November. Among them are the seeming unlikeliness of the business friendly governor Hochul approving either his plans for raising NYC’s debt limit or to raise taxes on city businesses and millionaires. Most importantly there is the risk of capital flight: the risk the city’s tax base will be wrecked as investors and businessmen move their money out of the city if Mamdani wins and attempts to pursue his mildly democratic socialist agenda. In order to rein in Mamdani, right wing libertarian Washington Post columnist Megan McCardle, posted on X a call for both Hochul to block Mamdani’s proposed expansionary fiscal policies and for NYC bond holders to conduct a sell-off of the city’s bonds. In order to govern NYC, Mamdani will have to gain the cooperation of NYC’s business elites, convincing them that his policies will be business friendly enough for them to remain in the city.

It is unclear at this point how much capital flight will occur if Mamdani wins election–or how far he will go to accommodate the establishment. One step in that accommodation was his decision to hire Jeffrey Lerner, former political director at the Democratic National Committee, as his communications director. Another is his reportedly frequent friendly conversations with ex-mayor Bill de Blasio, who has advised him about staffing his administration. De Blasio, whom Mamdani has pronounced as his most favorite of all recent NYC mayors, largely hewed to the neoliberal status quo while in office.

Mamdani is a serious person and it would be a shame if his mayorship turned into a resemblance to the mayorship of London, England by Ken Livingstone from 2000 to 2008. Livingstone, known as “Red Ken,” a left wing social democratic firebrand in the 1980s, substantially accommodated his policies to the city’s powerful financial and real estate interests–while also engaging in anti-imperialist rhetoric, including criticism of Israel.

It will be very interesting to see what happens. Grassroots movements will have to relentlessly hold Mamdani’s feet to the fire.

The Socialist Movement Led Zohran Mamdani to Victory

The two best analyses of Zohran Mamdani’s recent victory are this one, by Michael Thomas Carter, and this conversation that Daniel Denvir, the Terry Gross of the Left, hosted with two organizers in New York City. Both analyses focus on the elephant in the room.

Virtually all of the commentariat have emphasized Mamdani’s videos, his undeniable charisma and political fluency, and Andrew Cuomo’s weaknesses. The latter were oddly invisible to most commentators up until the very night that Cuomo conceded; then it became obvious that he was a weak candidate and was always going to lose; there’s a lesson there about power, which people always treat as static, when it’s not.

But easily the most important factor in Zohran’s victory is the movement that Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) have built in New York City since the Bernie Sanders campaign in 2016. Carter and the two organizers Denvir talks to — Gustavo Gordillo and Grace Mauser — provide both historical perspective and immediate nuts and bolts commentary. Make sure you read and listen to them.

I want to stress two elements in what I heard.

First, DSA has seen a lot of failures along the way. Failure is always a hard thing for social movements to deal with, particularly in the United States, where failure is the ultimate sin. But as Eve Weinbaum pointed out years ago in her excellent book To Move a Mountain, which I highly recommend, every movement meets failure. The only question is how it deals with failure, and Weinbaum has a rich and reflective analysis of just that question. DSA has figured out not only how to deal with failure but also how to grow from it. We saw the fruits of their labor on election night.

Second, yesterday, my wife and I went to a massive outdoor DSA party celebrating Zohran’s victory. What struck me most about the celebration was that it showed how much DSA has built a movement culture. You could see it in the way everyone was talking to everyone. Usually, at most New York gatherings, everyone is looking over each other’s shoulders to see who is not talking to them, whom they want to be talking to but can’t, who is more important than the person in front of them. Here, as I said, I saw everyone talking to everyone, wanting to reach out to each other, to the person next to them, to bring people in to the conversation. There were all kinds of sign-ups everywhere: runners for DSA, trans people for DSA, parents for DSA, city workers for DSA, and so on. The diversity, in terms of race and age, was impressive. This was a group of people — many, many hundreds, way out in Queens — that wanted to be with each other and wanted more people to be with them.

In his unpublished Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts, Karl Marx actually made a point of this exact moment in the development of the workers’ movement in France, which he witnessed firsthand while in Paris. The moment when the immediate and more instrumental political needs of collective action take off into something more generative:

When communist workmen gather together, their immediate aim is instruction, propaganda, etc. But at the same time they acquire a new need — the need for society — and what appears as a means becomes an end. This practical development can be most strikingly observed in the gatherings of French socialist workers. Smoking, eating and drinking, etc., are no longer means of creating links between people. Company, association, conversation, which in its turn has society as its goal, is enough for them.

There’s always a danger, of course, in any movement, that that need for company and association becomes narrow and clique-ish. But when movements are on the rise, when they’re robust, they tend to be just the opposite. That’s what I saw yesterday. And hope to see more of in the future.

To the Field First, Comrades!

To the New York Times, Zohran Mamdani’s insurgent mayoral campaign was “built from nothing in a matter of months.” For the Washington Post, he was “a political upstart with fresh ideas coming out of nowhere.” Even MSNBC’s Chris Hayes, who has covered left-wing movements more than most, told Ezra Klein that Mamdani “genuinely came out of nowhere.”

What makes these declarations of spontaneous inception so remarkable is not merely that they are wrong, but that they get it entirely backwards. While Mamdani’s ascent may have bypassed the traditional Democratic Party machinery, his campaign didn’t achieve this through individual genius, but through a decade of methodical collective effort.

A close look at the rise of Mamdani and the movement behind him yields both good news and bad news for a restless Democratic base looking to copy his success. The bad news is that there is no shortcut available: Mamdani’s rise was only made possible by a ten-year-long, door-to-door slog in the political trenches. The good news is that there’s no secret to it: It can be done; it just takes doing.

Mamdani’s success, according to mainstream narratives and prominent pundits, is due to a mixture of individual political acumen, social media savvy, a talented video production team, and his appealing message of a more affordable city for all New Yorkers. All of this helped, but the fact that Mamdani secured the most total votes in a primary in New York City’s history marks the culmination of a grassroots political project that began at least back in 2015, when the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) announced a “New Strategy for a New Era,” energized by the early days of Bernie Sanders’s first presidential run

Over the past nine years, NYC-DSA has built a field organizing machine that is arguably the strongest electoral operation in municipal politics nationwide. Through wins and losses in local, state, and federal elections, NYC-DSA has learned strategic lessons, developed significant logistical capacity, created a volunteer base for canvassing and outreach, and nurtured a cadre of experienced electoral campaign workers who work on endorsed campaigns.

NYC-DSA’s grassroots strategy began in the heart of what NYC political analyst Michael Lange calls “the commie corridor,” outer-borough neighborhoods stretching from Astoria, Queens to Sunset Park, Brooklyn. These areas are increasingly populated by younger leftists. NYC-DSA first organized Bushwick to help tenant organizer Debbie Medina’s State Senate campaign., Coming on the heels of Bernie Sanders’s 2016 primary campaign, Medina’s campaign received 40 percent of the vote in the Democratic primary, despite a tragic family scandal that forced the candidate to stop campaigning months before the primary. The extremely real estate friendly incumbent, Martin Dilan, remained a target for NYC-DSA, but would survive one more term before his eventual defeat by DSA-member Julia Salazar in 2018.

Next, NYC-DSA set its sights on the City Council, with the 2017 campaigns of then-teacher Jabari Brisport in Central Brooklyn and Palestinian Christian pastor Khader El-Yateem in South Brooklyn. Notably, El-Yateem’s campaign was the first NYC-DSA campaign that Zohran Mamdani supported by working as El-Yateem’s paid canvassing manager. This primary was an early expression of the alliance between Muslim immigrant communities and radical politics that contributed heavily to Mamdani’s primary win.

This coalition between democratic socialists and immigrant communities was not yet powerful enough to upend the existing South Brooklyn political scene. El-Yateem won 31% of the vote, but lost by eight points to the Working Families Party (WFP) candidate, current City Council Member Justin Brannan. NYC-DSA was then still an untested force—seen as too radical and impractical to be trusted by the institutional left of the WFP.

Meanwhile, up in Central Brooklyn, Jabari Brisport’s campaign continued to focus on opposing the designs of the real estate industry, hinging largely on his opposition to the controversial Bedford-Union Armory redevelopment project, which activists and many residents considered a giveaway of public land to a Trump-supporting developers for pennies on the dollar. Despite running as a Green in heavily-Democratic New York, Brisport secured 30% of the vote in the general election compared to 62% for the Democratic incumbent. Still, second place doesn’t get you a seat on the City Council, and the Bedford Union Armory project went through, with many of the promised community benefits never materializing.

What Works in New York: Primary The Democrats

Since then, NYC-DSA has exclusively run our candidates in Democratic primaries for several reasons.

First, many reliable New York voters are still loyal to Democratic party brand and can only be persuaded to vote for a candidate if they are nominally a Democrat. In New York, most of the “triple-prime” voters who vote in every primary are conditioned to see the Democratic primary as the only election that matters. In most cases, it is. Likewise, in most neighborhoods, most debates, policy conversations, and controversies happen in the runup to June, not November.

Second, running as a Democrat allows the campaign to compete for endorsements from advocacy organizations, labor unions, and elected officials who would otherwise rule out supporting an insurgent candidate. While Jabari was able to get endorsements from smaller organizations and a small labor union local, even ideologically aligned big players would rarely endorse a non-Democrat.

Third, primaries in New York have notoriously low turnout. Even last week’s high-profile mayoral primary garnered around 30% of eligible Democratic voters. While democratic socialists benefit from expanding the electorate, it’s easier to meaningfully expand an electorate of 1 million people rather than an electorate of 3 million people, especially through field organizing.

The successful campaigns of New York Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and New York State Senator Julia Salazar would demonstrate proofs of concept for these premises, creating a playbook for future grassroots campaigns including Mamdani’s.

In February 2018, I was brought on as the second staffer for the longshot congressional candidate Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. One of the organizations that formed in the aftermath of Bernie’s failed Presidential bid was Brand New Congress, which sought to run hundreds of candidates who had signed on to Sanders’ platform in both Republican and Democratic primaries. This organization eventually folded into the Justice Democrats. In 2018, they had recruited 12 candidates, including Ocasio-Cortez, and endorsed 79 others.

At that point, NYC-DSA had not yet endorsed Ocasio-Cortez, and there was some hesitation from the Justice Democrats about the baggage that comes along with the “democratic socialist” label.

Ocasio-Cortez, nonetheless, had been regularly attending meetings of both the Queens and Bronx/Upper Manhattan branch in hopes of gaining the NYC-DSA endorsement. Some DSA members were suspicious of whether her primary allegiance was to the more ideologically conventional Justice Democrats and wondered about her commitment to democratic socialism. Also, unlike the Justice Democrats, we weren’t supporting a large stable of endorsed candidates and would have to live with the consequences of our probable failure against one of the most powerful men in New York State politics. While they had races all around the country they were supporting, for us, this was a significant political risk: a low-probability but high-impact long shot. If we came at the king and missed, Crowley could easily bankroll our opponents in future electoral cycles, pressure influential organizations to blacklist our candidates, or even try to derail our tenant organizing and labor organizing efforts through his local political connections.

Despite these ideological and practical differences, there was also considerable ideological overlap between both groups, and the only two full-time staffers on the ground (Vigie Ramos-Rios and myself) were DSA members. Since we are a democratic organization, our endorsement process took some time. Ocasio-Cortez filled out policy questionnaires provided by DSA; attended endorsement forums where members asked her questions; and by April, she won the endorsement vote from both branches, unlocking NYC-DSA’s citywide network of volunteers, donors, and supporters.

In that race, we applied an early version of our “field-first” playbook using a volunteer force made up of NYC-DSA members, Justice Democrats, and local residents inspired by our message, especially immigrant communities. NYC-DSA’s Queens branch alone knocked more than 13,000 doors (while the Bronx/Upper Manhattan branch also did their part, their separated door count is sadly lost to time). We also hired two separate paid canvassing operations that contributed to extensive door-knocking operations across two boroughs, one of which was led by Rob Akleh, who went on to lead the paid canvassing effort of the Zohran Mamdani campaign. We won, precisely hitting our “win number” of 15,000 votes (57% of the vote). It greatly helped that we caught the Queens machine napping, with more than $1 million left in Crowley’s campaign account. As with Zohran, our coalition was much broader than just NYC-DSA, but it’s notable that among the 12 candidates recruited by Justice Democrats in 2018, she was both the only DSA-endorsed candidate and the only victor among them.

Over in Bushwick, our chapter had not forgotten about Martin Dilan and his coziness with the Real Estate Board of New York. At that time, congressional primaries were in June and state primaries were in September, so we had several months to take advantage of this momentum. We were already running DSA tenant activist Julia Salazar for the seat using this field-first approach, with campaign manager and DSA member Tascha Van Auken at the helm. Van Auken, who has bounced back and forth between politics and working in production for the Blue Man Group, is currently Zohran Mamdani’s field director and is probably the most well-respected field operative in NYC-DSA.

Salazar’s successful race is a telling case study of the power of a strong field operation, even in the face of scandal in the press (full disclosure, I was Senator Salazar’s Communications Director during her first term). While Ocasio-Cortez’s stealth victory was barely covered by the press , after she won and endorsed Salazar, the media grew much more interested in investigating democratic socialist candidates for office . Both mainstream and right-wing press hammered Salazar with a series of scandals. The mainstream publications uncovered inconsistencies with Salazar’s personal narrative, while The Daily Caller callously outed her as the victim of sexual assault.

Despite this steady drumbeat of negative media attention, NYC-DSA displayed a ruthless pragmatism and stuck by our candidate, determined to defeat the real estate-backed incumbent. We had chosen our candidate; we believed in her commitment to the cause; we knew that she would fight to protect our communities from further gentrification-driven displacement. The rest was noise. She won with 58 percent of the vote, underscoring the power of field organizing over the media narratives that obsess establishment politicians.

When asked by The Nation about how they had overcome these scandals, Van Auken pointed to NYC-DSA’s field operation, saying: “In all, 1,883 volunteers signed up for 4,663 canvassing shifts. Over the course of the campaign, supporters knocked on over 120,000 doors and had conversations with over 10,000 voters. That was a huge increase from the El-Yateem and Brisport campaigns, during which NYC-DSA knocked on about 20,000 doors for each.” By talking with neighbors anxious about their rent, canvassers foregrounded Salazar’s commitment to fighting for tenants, and NYC-DSA was able to neutralize the media narratives focused on discrediting Salazar as an individual. The movement was broader than any one person, so the media’s attempts to discredit her were ineffective. Our faith was rewarded the next year when Salazar was a key socialist voice in Albany during the intense struggle to pass 2019’s “Housing Stability and Tenant Support Act,” which finally made rent stabilization permanent in New York City and allowed upstate cities to institute rent stabilization. The New York Times called the legislation “a seismic shift…in the relationship between tenants and landlords.”

This result points toward one of the biggest tensions present within NYC-DSA. While it’s true that our chapter includes newcomers to the city—as shaped by decades of gentrification, and reinforced by NYC’s current political leadership—our electoral operation and legislative strategy consistently prioritizes fighting for longtime residents against further gentrification and the displacement pushed by the landlord lobby. While this coalition of transplants and longtime residents is not always comfortable, it has represented the foundation of our electoral and policy success, despite the bad-faith smears of establishment politicians whose decisions led to the gentrification they decry.

Organizing Toward the Mayoral Seat

Meanwhile, there was a broader struggle developing. The Independent Democratic Conference (IDC) was an organization of eight ostensibly Democratic lawmakers who caucused with Republicans in Albany. Despite public denials, it was an open secret that Andrew Cuomo created and sustained this conference, both to cement his near-absolute power in Albany and to allow him to blame the Republican-led Senate for the relatively conservative policies he supported. Cynthia Nixon was running for governor against Cuomo alongside a slate of challengers to the IDC backed by the Working Families Party. After an advisory vote of the membership, NYC-DSA’s Citywide Central Leadership Committee (CLC) voted to endorse Nixon for governor and Jumaane Williams for Public Advocate. This was somewhat controversial: some members felt that a millionaire celebrity without a strong attachment to NYC-DSA would not serve as an authentic representative of our politics. Nixon lost, but six out of eight of the IDC challengers she supported (as well as Julia Salazar) all won.

During this cycle, Mamdani was working on yet another South Brooklyn DSA member’s campaign. He worked first as the field director and then the campaign manager for writer and novelist Ross Barkan. Unlike the other campaigns featured in this article, however, Barkan did not obtain NYC-DSA’s endorsement, falling short of the internal vote threshold required to win endorsement. This was most likely due to concerns about capacity, as NYC-DSA was going all-out for Julia Salazar and had never before run two candidates for the same election date. Barkan is a self-described “Israel-skeptic Jew,” and was running in a district with both large numbers of Muslim voters and Orthodox Jewish communities. Barkan fell short, putting Mamdani at zero for two, but in both races he had shown an impressive organizing and managing capacity that marked him as a rising talent.

Mamdani’s two experiences running campaigns in relatively conservative South Brooklyn likely honed his ability to bridge the divide between Jewish and Muslim New Yorkers, which was exemplified by his successful alliance with Brad Lander in the June primary and his success among significant numbers of Jewish primary voters. The intensifying genocide in Gaza likely cemented this alliance as growing numbers of Jewish voters have become disillusioned with Netanyahu’s increasingly brutal government and even the Zionist project itself.

In every cycle after 2018’s watershed success, we have made steady progress iterating on this playbook, running several candidates for state or local offices while successfully defending our existing elected officials. In addition to those already mentioned, our victors include State Senators Kristen Gonzalez and Jabari Brisport State Assembly Members Phara Souffrant Forrest, Marcela Mitaynes, Emily Gallagher, Claire Valdez, and Zohran Mamdani; and City Council Members Tiffany Cabán and Alexa Avilés. All of these elected officials are what we used to call “open” socialists, as our membership does not usually endorse those who refuse to identify as such. The state-level electeds in this group are organized into a “Socialists in Office” committee (SIO) that coordinates our independent state legislative strategy.

We have also lost our fair share of races, but even the losses have built our capacity, created volunteer networks in new neighborhoods, trained new staff, and spread our ideals from the Bronx to Bay Ridge. We have developed an internally democratic endorsement process and political culture that ensures close organizational alignment between our membership and our candidates, especially what we call “cadre” candidates like Zohran, meaning candidates who have become politically active through their engagement with NYC-DSA.

To date, NYC-DSA has not only elected the first socialist State Senator in a century, but also can now claim a nationally famous congress member. Naturally, most DSA members became more concerned with ensuring that our elected officials authentically represent our movement. Joining the campaigns of inauthentic candidates who opportunistically seek endorsement to get a modicum of power became even less attractive to the membership, as we had shown the ability to elect candidates who consistently identified as democratic socialists. As a result, after 2018, our chapter moved away from endorsing candidates who primarily identify as progressives. While in this recent cycle, Mamdani’s alliance with Lander and the WFP slate speaks to our chapter’s willingness to strategically ally with other groups, the days when NYC-DSA would endorse a liberal candidate like David Dinkins as a junior coalition partner are now over.

Trust the Process, Trust the People: DSA’s Support Is Conditional

In our internal process, candidates submit questionnaires on their policy positions to the Electoral Working Group, then attend forums with the membership of the geographic branches they hope to represent in government. In these forums, rank-and-file members ask candidates questions. After this, the membership has an internal discussion (without the candidate present) to debate issues of organizational capacity, alignment with our principles, and any issues members might have with their questionnaires or answers.

One of the unique reasons our field operation is effective is that we don’t do “paper” endorsements, meaning that our endorsement is a commitment to an all-out field organizing effort aimed at winning the election. In these discussions, one of the perennial questions is whether we have members who are willing to regularly volunteer or become a canvassing lead. This means that we largely avoid the problem wherein a candidate receives an endorsement from an organization but the rank and file don’t fully and materially support the effort. This also means that connected insiders aren’t able to game the process easily because of individual personal relationships and obtain endorsements without being largely accountable to our membership.

These organizational structures have been built by our now nearly 10,000 citywide members. By incorporating the lessons from each cycle, we continue to expand our ambitions to the scale of our abilities. This organizational culture and structure is the incubator from which the Mamdani campaign grew. Mamdani filled out his questionnaires, spoke at a citywide town hall at the Church in the Village, and we voted to endorse him last October. He won endorsement with around 80% of the vote, with a turnout of around 6,000 people. As the campaign’s often-mentioned 50,000 volunteers started to sign up, a ready-made, citywide network of experienced field organizers were ready to help train them, dispatch them, and manage the logistics that made them so effective. It’s notable that, in Mamdani’s questionnaire, he said that he would not run at all if he did not receive our endorsement. While the coalition that coalesced around his campaign was much broader than NYC-DSA, in this very direct sense our organization is responsible for his mayoral run.

In making this commitment, Mamdani’s organizational discipline points toward one of the most important parts of this organizing machine: the big, scary “S” word, socialism. A membership-run democratic organizing machine works best because all of us are accountable to a specific approach to politics, a specific ideology of democratic socialism, and an ongoing historical tradition much broader than any individual. Our members insist that our candidates identify as democratic socialists not as a purity test, but as an accountability test. We largely avoid the issue of a charismatic person with vague positions and ideals hijacking our organizational power and betraying us, because they must remain accountable to our membership’s collective understanding of what democratic socialism means and how it should be practiced.

Because we stand for specific principles, we can mobilize members to act en masse for those principles. Our volunteers aren’t told to come out: they want to come out because they believe in our collective political project and they participated in the process that led to the candidate’s endorsement. Our collective wisdom has decided that while certain compromises need to happen in government, the candidate will fight hard for us and our movement while communicating the reasoning behind their decisions.

Notably, the issue that has come closest to requiring a complete break with DSA elected officials has historically been their commitment (or lack thereof) to Palestinian liberation and anti-Zionist politics. In 2021, after nationally endorsed Jamaal Bowman went to Israel with J Street, met with former Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennet, and voted for the Iron Dome, the National Political Committee debated expelling him from the organization altogether, ultimately deciding to allow him to remain but not to re-endorse him until he demonstrated solidarity with Palestine. However, in 2024, once Bowman was facing AIPAC-backed primary challenger George Latimer, he successfully made amends with NYC-DSA, though not National DSA, obtaining a last-minute endorsement around a month before the primary. This was partially because he reversed his position and agreed to support B.D.S. This was controversial because of the rushed nature of the endorsement and his past positions on the issue. Unlike Salazar, Brisport, and Mamdani, Bowman’s primary political home wasn’t DSA, but Justice Democrats. Bowman lost.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez faced a similar controversy in 2024 after she voted for a House resolution that labeled the “denial of Israel’s right to exist” as antisemitism and hosted a panel with Amy Spitalnick, CEO of the Jewish Council for Public Affairs, an organization that lobbies for a definition of antisemitism that includes anti-Zionism. The national press covered the fracas with AOC as an un-endorsement by DSA, but that wasn’t entirely accurate. After intense debate, DSA’s National Political Committee had decided to issue her an endorsement with strict conditions: opposition to all funding for Israel, support for the “Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions” movement, votes against all bills that conflate anti-semitism and anti-Zionism, and participation in a federal Socialists in Office committee.

By that point, Ocasio-Cortez had already won her primary in a landslide, and NYC-DSA’s leadership withdrew their request to national for endorsement, as these conditions had not been previously discussed with the candidate or the chapter. Some, moreover, felt that she would not abide by them, setting up an awkward conflict. The National Political Committee’s subsequent statement was widely covered as DSA’s wholesale rejection of Ocasio-Cortez, but NYC-DSA continues to have a relationship with her office and has not withdrawn our local endorsement. (DSA endorses at a both national and local level.) Some members still felt that she should have been censured or lost our local endorsement, and the next time she is up for reelection, they will no doubt voice their concerns.

Both of these incidents show a deep, and often justified, fear on the left that our candidates will accept our support only to betray us in office. DSA’s electoral political experiment is still young by historical standards. One day, one of our elected officials will stray so far from our principles that our membership will choose to actively oppose them. In that case, they may find themselves facing off against the very electoral field organizing machine that brought them to power in the first place.

Bowman, who did not come from our ranks and flip-flopped on whether he remained a member after the controversy, came to us seeking endorsement when he was in danger of losing his primary. If Bowman had been a more consistent and reliable member of the movement, he wouldn’t have needed to come to us last-minute, and he would have enjoyed the consistent and early support provided to candidates like Mamdani. While we endorsed Bowman as a tactical decision against a common enemy, the level of enthusiasm and support our members showed for his candidacy was limited by his own political history and decisions in office. Given the headwinds Bowman faced (particularly a much less favorably drawn district), it’s unlikely that deeper alignment between him and NYC-DSA would have put him over the top. However, his inconsistency certainly didn’t win him any friends in the Zionist lobby, and it’s hard to say that stronger support from NYC-DSA wouldn’t have helped his campaign.

NYC-DSA has created an organizing machine that does not just provide material support to our elected officials, but also places them into a political community that encourages accountability to our shared values. Candidates like Mamdani don’t just assume the democratic socialist label to get our endorsement: they practice democratic socialism as members of a broader organizational culture, making it a core feature of political life. Over the past nine years, we have worked together to radically change our city’s politics, bringing socialist ideals to the beating heart of U.S. capitalism and challenging the U.S. empire in the Empire State.

We also know that, even as a campaign ends, the fight is never over. The Democratic establishment is showing no signs of rolling over in the general election, which will require everything NYC-DSA has to give and then some. If, and when, Mamdani moves into Gracie Mansion, he’ll have a powerful array of forces lined up against him in the city, Albany, and the White House. Will it be enough to have the people with him? We intend to find out.

Zohran Mamdani’s last name reflects centuries of intercontinental trade, migration and cultural exchange

(The Conversation) — When Zohran Mamdani announced his candidacy for mayor of New York City, political observers noted his progressive platform and legislative record. But understanding the Democratic candidate’s background requires examining the rich cultural tapestry woven into his very surname: Mamdani.

He takes the name from his father, Mahmood Mamdani, a prominent academic who was raised in Uganda and whose work focuses on postcolonial Uganda. I studied the history of the Khoja community for my doctoral work and have helped develop Khoja studies as an academic discipline. The Mamdani surname tells a story of migration, resilience and community-building that spans centuries and continents.

The Khoja history

Mamdanis in Uganda belong to the Khoja community, a South Asian Muslim merchant caste, that shaped economic development across the western Indian Ocean for centuries.

The name originates from greater Sindh, a region in South Asia that today includes southeastern Pakistan and Kachchh in western India.

Its etymology is twofold. Mām is an honorific title in Kachchhi and Gujarati languages, meaning kindness, courage and pride. Māmadō is a local version of the name Muhammad that often appeared in surnames in Hindu castes that converted to Islam, such as the Memons.

The Khoja were categorized by the British in the early 19th century as “Hindoo Mussalman” because their traditions spanned both religions.

Over time, the Khoja came to be identified only as Muslim and then primarily as Shiite Muslim. Today, the majority of Khoja are Ismaili: a branch of Shiite Islam that follows the Aga Khan as their living imam.

The Mamdani family, however, is part of the Twelver community of Khoja, whose Twelfth Imam is believed to be hidden from the world and only emerges in times of crisis. Twelvers believe he will help usher in an age of peace during end times.

Around the late 18th century, the Khoja helped export textiles, manufactured goods, spices and gems from the Indian subcontinent to Arabia and East Africa. Through this Western Indian Ocean trading network, they imported timber, ivory, minerals and cloves, among other goods.

Khoja family firms were built on kinship networks and trust. They built networks of shops, communal housing and warehouses, and extended credit for thousands of miles, from Zanzibar in Tanzania to Bombay – now Mumbai – on the western coast of India.

Cousins and brothers would send money and goods across the ocean with only a letter. The precarious nature of trade in this period meant that families also served as insurance for each other. In times of wealth, it was shared; in times of disaster, help was available.

Khoja contributions in Africa

The Khoja became instrumental in building the commercial infrastructure of eastern, central and southern Africa. But the Khoja contribution to the development of Africa extended far beyond trade.

In the absence of colonial investment in public infrastructure, they helped build institutions that formed the foundation of the modern nation-states that emerged after colonization. The institutions both facilitated trade and established permanent communities.

For example, the first dispensary and public school in Zanzibar were constructed by a Khoja magnate, Tharia Topan, who made his wealth through the ivory and clove trades. Topan eventually became so prominent that he was knighted by Queen Victoria in 1890 for his service to the British Empire in helping to end slavery in East Africa.

The Khoja community continues to invest in East Africa. The most famous example is the Aga Khan Development Network, whose hospitals and schools operate in 30 countries. In places such as Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania, they are considered the best.

Khoja in Uganda

Like in other parts of Africa, the Khoja settled in Uganda as a liaison business community to develop a market to serve both African and European needs. The linguistic and cultural knowledge, developed over centuries, helped facilitate business despite the challenges of colonization.

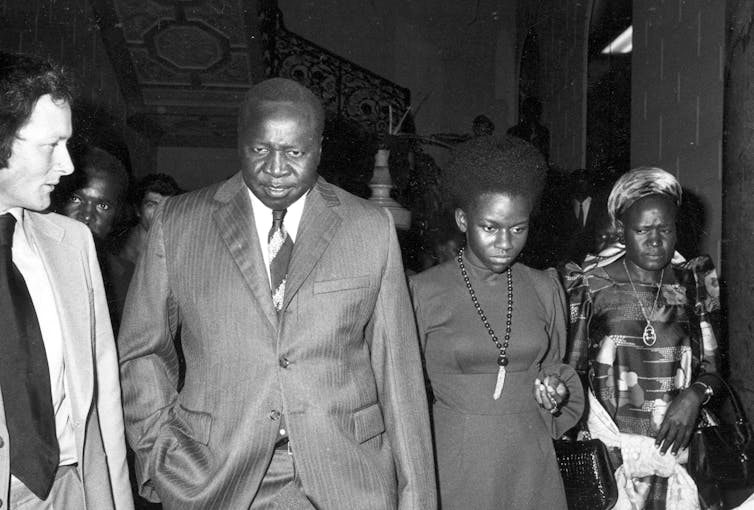

Ugandan President Idi Amin and his wife, Sarah, in Rome on Sept. 10, 1975.

AP Photo

However, in 1972, Ugandan dictator Idi Amin expelled all Asians – approximately 80,000 – forcing families like the Mamdanis into exile. These included indentured laborers, who were brought in to help build the railroad and farm during the British colonial period, and free traders, like the Mamdani family.

Amin saw them all as the same and famously said: “Asians came to Uganda to build the railway. The railway is finished. They must leave now.”

The experience was a bitter one. Families lost everything, and many left with only the clothes on their backs.

Mahmood Mamdani, who came from a Khoja merchant family, was 26 when he was exiled. Yet, unlike most Ugandan Asians, he chose to go back. At Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda’s capital, Mamdani set up the Institute for Social Research, which helped to provide rigorous social science training to Ugandan researchers trying to improve their society.

While the earlier generations of the Khoja tended to choose business or adjacent professions, such as accounting, the subsequent generations – particularly those educated in the West – embraced the knowledge economy as professionals, academics and nonprofit leaders.

Several of Mahmood Mamdani’s generation of Khoja academics conducted path-breaking work on Afro-Asian solidarity – a way of thinking about the world beyond colonial categories, such as the category of religion as a separate domain from the secular. These scholars, such as Tanzania’s Issa Shivji and Abdul Sheriff, worked on creating solidarity among the newly independent states of the Global South.

Mahmood Mamdani is known for his influential post-9/11 academic work, “Good Muslim, Bad Muslim,” which examined how Muslim identities are stereotyped. He argued that these identities are complex and varied, shaped by accumulated history and present experiences.

Interfaith identity

The Khoja community – known globally as the Khoja Shia Ithnasheri Muslim Community – has developed strong transnational connections. Today, they are concentrated in the United Kingdom, Canada, United States and France. However, Khoja can be found in almost any country in the world. In 2013, I met members of the community in Hong Kong.

The Khoja community plays an important role in interfaith dialogue and global development initiatives. A prominent Ismaili Khoja, Eboo Patel, the founder of Interfaith America, has dedicated his life to pluralism and mutual understanding through building up civil society.

Zohran Mamdani’s mother, acclaimed filmmaker Mira Nair, is Hindu by birth. This interfaith marriage exemplifies the flexibility, diversity and tolerance of Khoja Islam, which has historically navigated between Hindu and Islamic traditions.

Whether Mamdani’s policies prove practical remains to be seen, but his background offers something valuable: a deep understanding of how communities build resilience across generations and geographies.

(Iqbal Akhtar, Associate Professor of Religious Studies, Florida International University. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

![]()

No comments:

Post a Comment