December 28, 2025

By rasia Review

Gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) are among the most powerful explosions in the Universe, second only to the Big Bang. The majority of these bursts are observed to flash and fade within a few seconds to minutes. But on 2 July 2025, astronomers were alerted to a GRB source that was exhibiting repeating bursts and would end up lasting over seven hours. This event, dubbed GRB 250702B, is the longest gamma-ray burst humans have ever witnessed.

GRB 250702B was first identified by NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope (Fermi). Shortly after space-based telescopes detected the initial bursts in gamma-rays and pinpointed its on-sky location in X-rays, astronomers around the world launched campaigns to observe the event in additional wavelengths of light.

One of the first revelations about this event came when infrared observations acquired by ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) established that the source of GRB 250702B is located in a galaxy outside of ours, which until then had remained a question.

Following this, a team of astronomers led by Jonathan Carney, graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, set out to capture the event’s evolving afterglow, or the fading light emissions that follow the initial, extremely bright flash of gamma-rays. The properties of these emissions can provide clues about the type of event that caused the GRB.

To better understand the nature of this record-breaking event, the team used three of the world’s most powerful ground-based telescopes: the NSF Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope and the twin 8.1-meter International Gemini Observatory telescopes. This trio observed GRB 250702B starting roughly 15 hours after the first detection until about 18 days later. The team presents their findings in a paper published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The Blanco telescope is located in Chile at NSF Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO), a Program of NSF NOIRLab. The International Gemini Observatory consists of the Gemini North telescope in Hawai‘i and the Gemini South telescope in Chile. It is partly funded by the NSF and operated by NSF NOIRLab.

“The ability to rapidly point the Blanco and Gemini telescopes on short notice is crucial to capturing transient events such as gamma-ray bursts,” says Carney. “Without this ability, we would be limited in our understanding of distant events in the dynamic night sky.”

The team used a suite of instruments for their investigation: the NEWFIRM wide-field infrared imager and the 570-megapixel DOE-fabricated Dark Energy Camera (DECam), both mounted on the Blanco telescope, and the Gemini Multi-Object Spectrographs (GMOS) mounted on Gemini North and Gemini South.

Analysis of the observations revealed that GRB 250702B could not be seen in visible light, partly due to interstellar dust in our own Milky Way Galaxy, but more so due to dust in the GRB’s host galaxy. In fact, Gemini North, which provided the only close-to-visible-wavelength detection of the host galaxy, required nearly two hours of observations to capture the faint signal from beneath the swaths of dust.

Carney and his team then combined these data with new observations taken with the Keck I Telescope at the W. M. Keck Observatory, as well as publicly available data from VLT, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope (HST), and X-ray and radio observatories. They then compared this robust dataset with theoretical models, which are frameworks that explain the behavior of astronomical phenomena. Models can be used to make predictions that can then be tested against observational data to refine scientists’ understanding.

The team’s analysis established that the initial gamma-ray signal likely came from a narrow, high-speed jet of material crashing into the surrounding material, known as a relativistic jet. The analysis also helped characterize the environment around the GRB and the host galaxy overall. They found that there is a large amount of dust surrounding the location of the burst, and that the host galaxy is extremely massive compared to most GRB hosts. The data support a picture in which the GRB source resides in a dense, dusty environment, possibly a thick lane of dust present in the host galaxy along the line-of-sight between Earth and the GRB source. These details about the environment of GRB 250702B provide important constraints on the system that produced the initial outburst of gamma-rays.

Of the roughly 15,000 GRBs observed since the phenomenon was first recognized in 1973, only a half dozen come close to the length of GRB 250702B. Their proposed origins range from the collapse of a blue supergiant star, a tidal disruption event, or a newborn magnetar. GRB 250702B, however, doesn’t fit neatly into any known category.

From the data obtained so far, scientists have a few ideas of possible origin scenarios: (1) a black hole falling into a star that’s been stripped of its hydrogen and is now almost purely helium, (2) a star (or sub-stellar object such as a planet or brown dwarf) being disrupted during a close encounter with a stellar compact object, such as a stellar black hole or a neutron star, in what is known as a micro-tidal disruption event, (3) a star being torn apart as it falls into an intermediate-mass black hole — a type of black hole with a mass ranging from one hundred to one hundred thousand times the mass of our Sun that is believed to exist in abundance, but has so far been very difficult to find. If it is the latter scenario, this would be the first time in history that humans have witnessed a relativistic jet from an intermediate mass black hole in the act of consuming a star.

While more observations are needed to conclusively determine the cause of GRB 250702B, the data acquired so far remain consistent with these novel explanations.

“This work presents a fascinating cosmic archaeology problem in which we’re reconstructing the details of an event that occurred billions of light-years away,” says Carney. “The uncovering of these cosmic mysteries demonstrates how much we are still learning about the Universe’s most extreme events and reminds us to keep imagining what might be happening out there.”

It marks latest launch in growing Iran-Russia space cooperation amid Western criticism

Syed Zafar Mehdi |28.12.2025 - TRT/AA

TEHRAN, Iran

Iran on Sunday successfully launched three new satellites into space aboard a Russian Soyuz rocket in Russia’s Far East.

The satellites – Kowsar 1.5, Paya, and Zafar-2 – represent the latest chapter in a series of Iranian satellite launches in recent years, many of which have been carried out with Russian cooperation.

The Soyuz carrier also carried payloads from other countries, including Kuwait and Belarus.

The Kowsar 1.5 satellite is an upgraded version of Iran’s previous remote-sensing platform, designed for high-resolution imaging with a focus on agricultural applications, according to Iranian officials.

It was developed by a local knowledge-based company in collaboration with the Iranian Space Agency, highlighting growing cooperation between the public and private sectors.

Zafar, another upgraded satellite, is an advanced Earth-observation platform designed and built by Iran University of Science and Technology.

Weighing approximately 100 to 135 kilograms, it is intended to transmit high-resolution images for monitoring and managing natural resources, according to reports.

Paya, the heaviest of the three satellites, was produced by Iran Electronics Industries in collaboration with the Iranian Space Agency. Weighing about 150 kilograms, it is a remote sensing satellite and considered one of the most advanced domestically built imaging satellites.

The launch was widely followed in Iran with a live telecast by the state broadcaster.

There has been no reaction so far from the US or its European allies on the latest launch. They have often expressed concerns over Iran’s space launches, claiming they violate UN Security Council resolutions. Iran has, however, rejected these claims.

In a statement released ahead of Sunday’s launch, Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi emphasized that Iran’s satellite program is civilian and scientific in nature and expressed the ministry’s full support for the Iranian Space Agency.

“Iran’s activities in nuclear science, defense industries, nanotechnology, and satellite development are entirely peaceful and intended for peaceful purposes,” he said.

While many of Iran’s satellite launches in recent years have faced technical difficulties, this latest launch further strengthens cooperation between Iran and Russia in space technology.

Kazem Jalali, Iran’s ambassador to Russia, speaking ahead of the launch on Sunday, said that Tehran-Moscow collaboration in the space sector is extensive.

He noted Russia’s leading role in space affairs, including satellite technology, launch vehicles, and satellite deployment, saying the latest launch marks the seventh Iranian satellite to be carried into space by Russia.

New race to the moon: could a German be first this time?

Copyright Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

By Sonja Issel

Published on 28/12/2025 - EURONEWS

Man is returning to the moon - and with him old rivalries and new ambitions. Europe wants to have its say; Germany wants to be at the forefront. A historic opportunity beckons for Berlin.

Humans are due to land on the moon again in 2027—a return that comes at a time of growing geopolitical tensions reminiscent of the Cold War in many respects: rearmament, new power blocs, and increasing tensions between East and West.

As in the past, space has once again become a stage for strategic competition. A new landing on the moon stands for far more than scientific progress: it is seen as an expression of technological leadership and geopolitical power in the new space race. A permanent presence on the moon promises influence on future space standards, questions of resource utilisation and international cooperation.

The ambitions are correspondingly high. In addition to the USA and Europe, Russia and China in particular are currently pushing ahead with their own programmes. In this context, the European Union is increasingly coming into focus. Not only as a partner of the USA, but increasingly as an independent player in space.

This raises a new question: could this race end with a German on the moon for the first time?

US lunar programme with a European signature

The return of humans to the moon is part of the NASA-led Artemis programme. The United States is leading the way, while international partners—above all the European Space Agency (ESA)—are playing a central role.

A manned orbit of the moon is planned for the first half of 2026 with Artemis 2. One year later, Artemis 3 will see astronauts land on the lunar surface for the first time since 1972. In the long term, the programme also envisages the construction of the Gateway lunar station.

Europe is involved not only politically but also technologically. A key component of the missions is the European service module of the Orion spacecraft, which is being developed by ESA on behalf of NASA and largely built in Germany.

This role could now even be honoured with a priority on the moon: The head of the ESA, Josef Aschbacher, explained that he had decided that the first Europeans on a future moon mission should be astronauts of German, French, and Italian nationality. Germany should make the start.

Gerst as the Gagarin of the 21st century?

Four Germans are currently hoping for a ticket to the moon. As things stand today, Alexander Gerst and Matthias Maurer are considered the most promising candidates.

Gerst, a geophysicist and volcanologist, and Maurer, a materials researcher, have already been on the International Space Station (ISS) and are members of the European Space Agency's (ESA) active astronaut team.

Experience is particularly crucial for the selection process: according to current criteria, only astronauts who have already been in space can be considered for a mission to the moon. The two German reserve astronauts, Amelie Schoenenwald, a biochemist, and Nicola Winter, do not yet fulfil this requirement.

However, as it could still be a few years before an actual moon mission is scheduled, it cannot be ruled out that they will also have space experience by then, and therefore also have a chance.

Gerst is already open to a mission to the moon. When asked whether he could imagine a flight to the moon, he replied, "Of course."

For him, these missions have numerous benefits. Those who play an active role in the lunar programme will also remain at the forefront of key future technologies in space travel—for example, in earth observation, climate research, and Europe's technological autonomy.

Whether a German astronaut will actually be among those who set foot on the Moon cannot be determined at this stage, Gerst said. In his view, this would in any case require a significantly stronger involvement of the European Space Agency in providing key components for the missions.

Europe's striving for independence

However, a European on the moon also has great symbolic significance for Europe. Despite its close co-operation with NASA, Europe remains dependent on the USA in many areas of space travel. At the same time, the European Union is pursuing the goal of becoming more technologically independent.

This strategy is receiving a boost from a record budget for the European Space Agency (ESA). The member states are providing almost 22.1 billion euros for the years 2026 to 2028. One focus is on Europe's independent access to space.

Germany wants to define its role within this framework—as Europe's strongest economic power, preferably at the forefront. Research Minister Dorothee Bär (CSU) speaks of space travel "Made in Germany."

It seems to be no coincidence that her department has officially included the term "space" in its name since the start of the new legislative period.

With 5.1 billion euros, Germany is the largest contributor to the ESA. According to Bär, investment in space travel is necessary despite tight budgets—not only as an investment in the future, but also as a contribution to European sovereignty and security.

Competition in space

Other major powers also have ambitions beyond Earth. In Russia, for example, the state space agency Roskosmos is planning to spend billions and wants to involve private investors to a much greater extent than before.

Among other things, it plans to set up its own satellite internet service modelled on Starlink, which, according to Roskosmos CEO Dmitry Bakanov, is due to launch in 2027.

However, Russia's prospects in the new race to the moon are currently considered limited. Experts are expecting delays due to logistical and financial problems. The Luna-26 moon mission has already been postponed to 2028.

China, on the other hand, is much more dynamic. The People's Republic is pushing ahead with its space programme at a rapid pace and is increasingly positioning itself as a strategic competitor to the USA. The official goal is to launch a manned mission to the moon by 2030, even if Beijing has so far revealed little about specific timetables.

A symbolic first step towards the moon

As far as Germany is concerned, the journey to the moon could begin as early as 2026—but not directly with a German astronaut for the time being. The Italian designer Giulia Bona, who lives in Berlin, has created a mascot that could fly into space on NASA's Artemis 2 mission.

The design shows a small astronaut on the shoulder of a giant called Orion, named after the mission's space capsule and also an allusion to the mythology in which Orion is associated with the goddess Artemis. Such so-called zero-G indicators have a long tradition: Yuri Gagarin is said to have taken a small lucky charm with him into space in 1961.

Bona said she took part in the competition spontaneously. The fact that her design made it to the final round was an "unexpected joy" for her.

She now hopes to see her mascot floating between the astronauts in the live stream when Artemis 2 is launched, which would at least be a symbolic first step for Germany towards the moon.

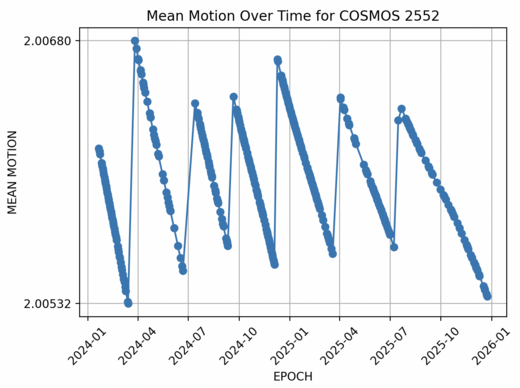

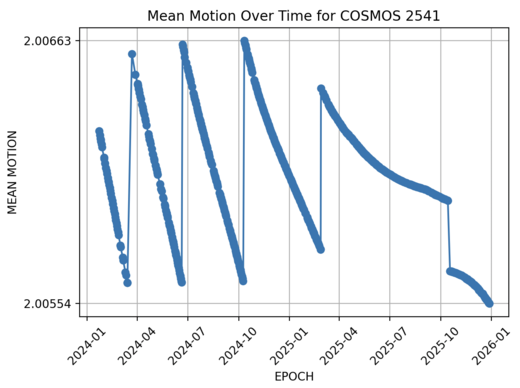

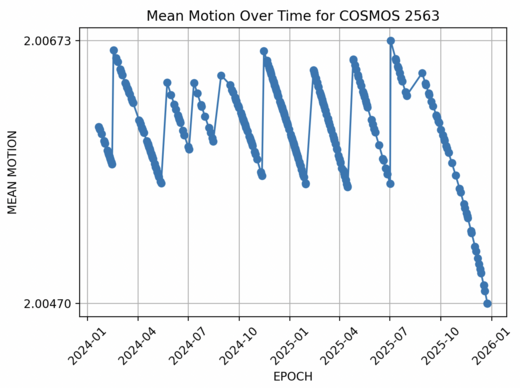

Orbital data suggest that as of the end of 2025 Russia may have only one functioning early-warning satellite of the Tundra type. This is a significant decline from the situation in March 2025, when three satellites of the constellation - Cosmos-2541 (launched in September 2019), Cosmos-2552 (November 2021), and Cosmos-2563 (November 2022) - appeared to be operational.

Orbital data suggest that as of the end of 2025 Russia may have only one functioning early-warning satellite of the Tundra type. This is a significant decline from the situation in March 2025, when three satellites of the constellation - Cosmos-2541 (launched in September 2019), Cosmos-2552 (November 2021), and Cosmos-2563 (November 2022) - appeared to be operational.

Now it appears that for Cosmos-2541, the orbit correction maneuver successfully conducted in March 2025 was the last one. Another satellite of those three, Cosmos-2563, appears to have failed at some point after the last successful maneuver in July 2025. Images below show the changes in mean motion that testify to the failures.

The only satellite that doesn't show clear signs of failure is Cosmos-2552, launched in November 2021. However, based on recent patterns, it should have performed an orbit correction sometime in November 2025 (see the main image in the post). But it is too early to say that Cosmos-2552 has ended its operations.

I should note again that the apparent loss of early-warning satellites is not necessarily a cause for alarm. Russia does not rely on the space-based segment of its early-warning system to the extent the United States does. For a discussion, see this 2015 post or my Science & Global Security article.

No comments:

Post a Comment