Ishmael Reed

December 19, 2025

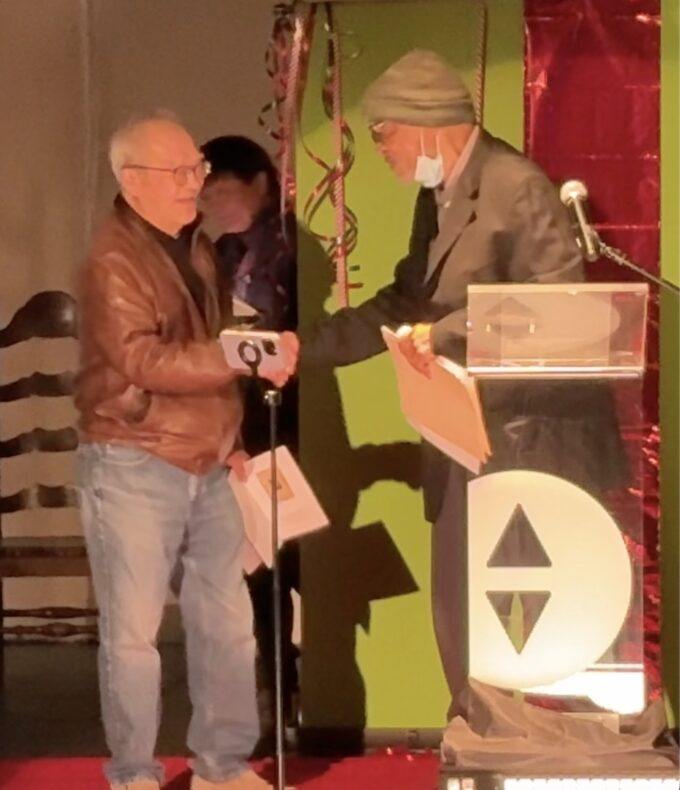

Ishmael Reed presenting William Gee Wong with the American Book Award for memoir. Photo: Tennessee Reed.

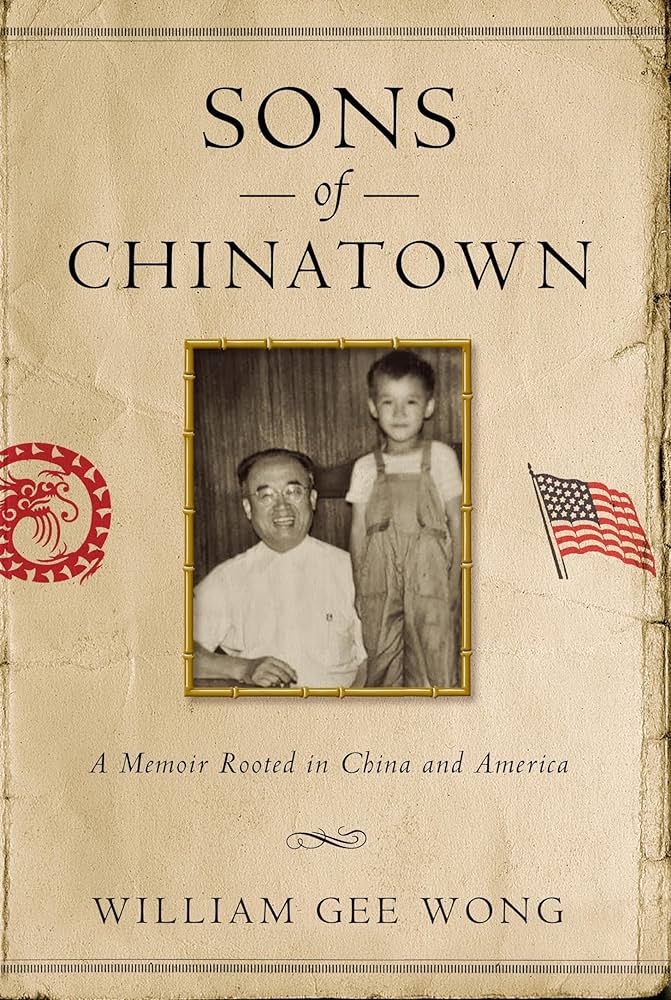

Reading William Gee Wong’s Sons of Chinatown: A Memoir Rooted in China and America (Temple University Press, 2024), one realizes how valuable the former Oakland Tribune publishers Robert and Nancy Maynard were to the Oakland community. However, the stress that accompanied their being overachievers killed them—the Jackie Robinson curse. Maynard, who’d worked at The Washington Post, had become the first Black publisher of a major metropolitan newspaper. One of those who thrived there was William Gee Wong. The newspaper received a Pulitzer Prize, and Wong got a spot on The McNeil-Lehrer Report, a plum for a minority journalist. While dwelling in the heights of journalism, Wong learned the different treatment accorded to white and minority journalists.

Plagiarist Mike Barnicle still has a job, a white male journalist who was suspended by The New York Times for sexual harassment, and Glenn Thrush still has a job at The Times. CNN commentator Jeffrey Toobin, who exposed himself to women on The New Yorker’s staff, a criminal offense, was also suspended. Briefly. He’s the one who said that the Black jury acquitted O.J. Simpson because Blacks can’t think rationally and “shouldn’t be patted on the head.” The jury wasn’t all Black, and the criminal’s gloves never did fit. Toobin still has a job at CNN. In late December 2017, Amber Athey reported about MSNBC’s Chris Matthews as having had a track record of sexual harassment toward female colleagues and guests, including one woman being given “a separation-related payment.” He retired, temporarily,but he’s back now.

Wong’s heady media moment came to an end when one of the good old boys of the kind who still control the media, the late C. David Burgin, became the newspaper’s editor after Robert Maynard’s death. Wong’s and Black journalist Brenda Payton’s roles were limited by the new owner, Burgin, who regularly insulted Maynard’s reign at the Tribune. Payton stayed on for a while, but Wong was fired. He was escorted from the building by a bouncer. So was Barbara Reynolds, who had a column at USA Today. She had a heart attack the night of her ouster.

With the current purge of minority journalists in the name of Woke and DEI, the Burgin types are in complete control of the mainstream media. Mainstream publications like The Washington Post and The Los Angeles Times have capitulated to Trump, and a pro-Trump family, the Ellisons, is about to buy Warner Bros., Netflix, and other media. Trump wants to control CNN through Ellison.

A media that lacks diversity attracts white readers by offering the usual stereotypes of communities that don’t have the media power to fight back. Though the corporate media believes its owners’ values are superior to those of social media platforms, social media offers a more multidimensional view of the communities we live in.

Fortunately, we still have ancient means to tell our stories: documentaries, theater, and books. Wong has chosen to write a book.

And so, deprived of the kind of space accorded to plagiarists like Barnicle, William Gee Wong has written Sons of Chinatown, and though this book is an account of Wong’s personal journey as a Chinese American and a husband with a biracial son, his story intersects with our stories. As Leonard Peltier says, the purpose of our faux Eurocentric education was to take the Indian out of the Indian. The purpose was also to take the Chinese out of the Chinese, the Hispanic out of the Hispanic, the Irish out of the Irish, and the Italian out of the Italian.

When Gay Talese, who bragged about marrying into the Anglo mainstream and denied the existence of Italian American literature, he was countered by Helen Barolini, author of The Dream Book, which documented a history of Italian American writing in the United States.

Wong felt this “weird insider-outsider phenomenon and ultimately came away knowing that I am an American by nationality and this indefinable cultural mix of Chinatown and American. Yet at the same time, I wasn’t sure—and in some ways, still am not—whether my broad cohort (Chinese Americans and Asian Americans), and I truly belong here in America or in our ancestral lands—or in truth, neither place, as though we are in a yellow purgatory. It is indeed an underlying weird feeling of belonging and yet not belonging.” All of us who have commuted between the worlds of our forefathers and mothers and the Anglo world have felt that way.

Wong found himself out of place in China, the country of his ancestors’ origin. Similarly, when Africans began visiting Africa in the 1960s, they discovered that the Africans considered them to be white. Wong feels uneasy about the hi-tech Chinese immigrants who speak Mandarin and look down upon the traditional Chinese Americans who speak Cantonese, who are slighted in the film “Crazy Rich Asians.” Without this book, most of us would have missed this slight just as I would have missed how Asian groups are pitted against each other in the Bruce Lee films if novelist Shawn Wong hadn’t alerted me. Traditional Black Americans complain about their treatment by African immigrants, especially the Nigerians, the most educated among immigrants. Joy Reid says her Guyanese mother and Congolese father made disparaging remarks about Black Americans. Blacks are also beset by high-tech Indian types who are even more eager to pick fights with Blacks to please white nationalists. They wouldn’t be the first immigrants to audition for white acceptance by craping on Blacks.

Vivek Ramaswamy,when a Republican presidential candidate, expressed sympathy for a White man who killed three Black people at a Jacksonville, Florida, Dollar General store. He didn’t think a mistaken belief in White supremacy was to blame, since he doesn’t think it exists, even though the killer had written a manifesto and had a swastika on his AR-15. Another Indian American who sought to gain the spotlight by kowtowing to white prejudices was Rina Shah, who justified Trump’s National Guard occupation of Washington, D.C., because of Black dysfunctional households. By doing so, she neglected dysfunction in her own community, including South Asian domestic violence, from a study: South Asian Women at Greater Risk for Injury From Intimate Partner Violence by Anita Raj, and Jay G Silverman.

“Intimate partner violence and intimate partner violence–related homicide disproportionately affect immigrant women.1–6 South Asian women residing in the United States appear to be at particularly high risk for intimate partner violence, with 40% reporting intimate partner violence in their current relationship in a recent study.” Ain’t no money or attention in Ms Raj.examining dysfunction in her community?

What Shah and Ramaswamy have in common with minority writers is that we are told that to be successful, we must attract a white audience because only whites buy cultural products. I’m sure that President Obama scolded Blacks with stern love lectures to convince white voters that he wouldn’t be a Black nationalist president. Wong writes about some deranged Black people who answered President Trump’s “Chinese Virus” smear by attacking Asian American citizens. Yes, like members of other ethnic groups, Blacks can be stupid. But an Asian American drug gang that sought to take over our neighborhood was repelled by a Black felon who’d been released from Pelican Bay. The police were of no help. In fact, at the Crime Council meetings where we met with the police, elderly Black residents wondered why the police were so chummy with drug dealers. Whites commit most of the violence against Asian Americans. Still, the media low-balls their participation because they don’t want to risk embarrassing those whom their advertisers see as their best customers. Don Lemon told me that at CNN, he was told to lighten up on Trump voters because MAGAs buy products too.

Wong writes: “Did my racial identity and/or my frequent writing about Chinese America and Asian America help or hurt my career? That question is knotty, convoluted, and difficult to grasp logically and rationally. I don’t really know. What I do know is that I have absolutely no regrets that I spent part of my journalism life writing about an aspect of American life—Yellow America—that few, if any, other mainstream journalists bothered to examine at the time I was doing it.” While many mediocre white journalists dominate the opinion industry highly qualified journalists William Gee Wong and Emil Guillermo were losttheir positions as commentators by PBS and NPR. (NPR fired me for my commentary about how the Willie Horton campaign would backfire on President Bush and Lee Atwater.)

Both Wong and Guillermo ascended to the heights of American journalism only to be cut down. But without their sacrifice and those of others, there would not have been a Yellow Renaissance in literature, because when members of the younger generation saw them use writing as an expression, they began writing themselves. Despite the setbacks Wong has encountered,he is still hopeful.

Wong writes: “America is no longer a place where only straight white Christian men are all-powerful and preeminent. Make no mistake: Many still are, but an increasing number of ‘others’ are making their marks, too—yes, including some of us yellow people. America’s challenge now and into the foreseeable future is to find ways to fit its many disparate identities into a more cohesive whole (i.e., a More Perfect Union).”

Like Baldwin, Wong writes about a corner of the American experience that exists in the shadows and about which Baldwin’s “Chorus of Innocents” is ignorant. William Gee Wong does the same with Sons of Chinatown, with equal eloquence. He is the Yellow Baldwin.

Reed’s latest play is “The Amanuensis.”

No comments:

Post a Comment