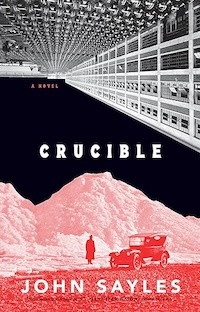

An Epic About Capitalism and Detroit

Detail from Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industrial Murals, Detroit Institute of Art. Photo: Jeffrey St. Clair.

John Sayles is a fantastic storyteller. Most people who share this viewpoint probably know Sayles from his films, which include Eight Men Out, Matewan and Return of the Secaucus 7. While those films certainly are among some of the best films in the last fifty years, it’s through his writing that I know Sayles best. I first read his story “At the Anarchists Convention” in the February 1979 issue of Atlantic Monthly. It was one of those afternoons when I was hanging out at the public library in downtown San Diego, California. Perusing the magazine shelves, I picked up that issue and glanced at the table of contents. Two things captured my interest: an article by Stephen Kinzer about the revolutionary forces in Nicaragua and a short story with the seeming contradiction of an anarchists’ convention. After finding a seat, I read the two submissions. Kinzer’s article didn’t exactly jibe with my understanding of the revolutionaries in Nicaragua, but it was decent stuff for a mainstream liberal magazine. John Sayles’ short story made me laugh, while his ability with words was a lesson in composition. I looked up his name in the card catalog and found that he had published two books—Pride of the Bimbos and Union Dues and in the weeks that followed read both.

Sayles made many more films in the next decade. His next novel Los Gusanos was published in 1991. Since then, he has published five more novels, all of them being what I would call epics, as in a long poem or narrative describing heroic deeds. To clarify, it’s not like Sayles novels are on par with ancient tales like Odysseus or even the Old Testament. However, the deeds of his protagonists inside these fictions of modern life can certainly be considered heroic within the context of the story being told. The most recent is titled Crucible and tells a story centered around the motorcar mogul and megalomaniac Henry Ford. The time period the tale takes place runs from the mid-1920s to the late 1930s. The characters portrayed include workers, company thugs, union organizers, their families and their women. The profit-driven fantasy of Ford’s that resulted in the construction of a village in the rubber-producing jungles of Brazil is but one location in the webs of power, corruption and capital woven by Henry Ford. So too, are his antisemitism, white supremacism, interest in Nazism and the paranoia and ego that informs it all.

In the Amazonian village constructed to produce rubber, there’s a young girl named Kerry whose father is assigned to manage the whole show. The girl’s natural curiosity and heightened intellect influence her interactions with the locals, even creating a teen romance for the times between her and an indigenous lad who is equally curious and  smart. The experiment in rubber cultivation ultimately fails, the economic crash being only one of the reasons. Meanwhile, back in Detroit union organizers are making headway amongst the workers. Unlike the failed jungle town, the economic crisis is the primary reason for this unforeseen (in the minds of management) transfer of loyalties among Ford company workers. Interwoven and splashed across the growing struggle between Ford’s capital and the United Autoworkers (UAW) organizing are the omnipresent curses of US history; curses manipulated by CEOs and anti-union forces even today—racism, sexism and anti-immigrant hatred. These phenomena appear discreetly in the conversations the author creates for his characters and violently in the actions of police, scabs and their protectors. They are not only present in the boardrooms and banquet halls of the owners; they are understood in their conversations and in the orders they send to the cops and private police fighting workers in the streets.

smart. The experiment in rubber cultivation ultimately fails, the economic crash being only one of the reasons. Meanwhile, back in Detroit union organizers are making headway amongst the workers. Unlike the failed jungle town, the economic crisis is the primary reason for this unforeseen (in the minds of management) transfer of loyalties among Ford company workers. Interwoven and splashed across the growing struggle between Ford’s capital and the United Autoworkers (UAW) organizing are the omnipresent curses of US history; curses manipulated by CEOs and anti-union forces even today—racism, sexism and anti-immigrant hatred. These phenomena appear discreetly in the conversations the author creates for his characters and violently in the actions of police, scabs and their protectors. They are not only present in the boardrooms and banquet halls of the owners; they are understood in their conversations and in the orders they send to the cops and private police fighting workers in the streets.

Certain protagonists imprint themselves in the reader’s mind, in part due to their relatability and in part because of Sayle’s mastery of the art of fiction. I found the communist labor organizer Rosa to be as genuine as the foreman in Brazil Jim Rogan’s daughter; the African-American autoworker Zeke as rounded a human being as the Polish worker called Kaz. The scenes inside the factories smell of steel, ring with industrial noise and rival the fear, anger and attitude of the men and women standing opposite well-armed cops of all kinds in the struggle for a union. Merriam-Webster suggests that the word crucible came from the “medieval Latin crucibulum, a noun for an earthen pot used to melt metals”. Over time, it has also acquired the definition which one undergoes a severe trial; a “place or situation in which concentrated forces interact to cause or influence change or development.” Considering all of these definitions in regards to this novel titled Crucible, it becomes clear that each description fits in its own way. The aforementioned Zeke works in a furnace room with most of the other African-American workers melting ore into steel. The international economic crisis and the onset of fascism and war provide a severe test at a time which results in changes unforeseen, as in the crucible of war and depression, death and repression. As the title of the novel, the word Crucible describes the work wholly and completely.

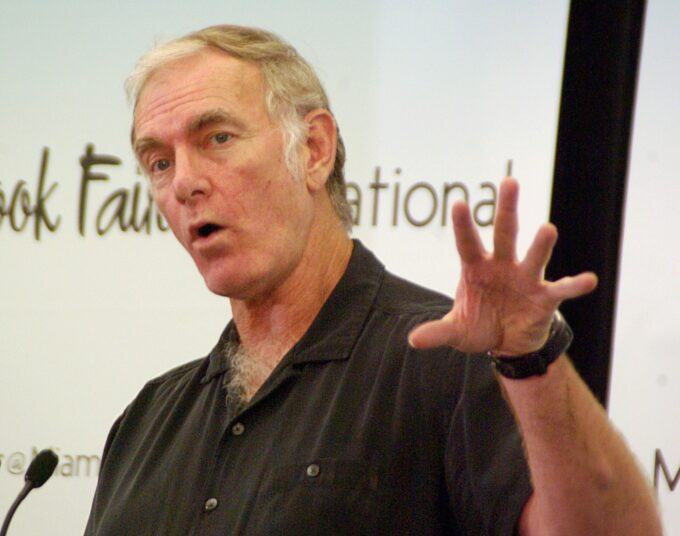

Nobody Starts With a Blank Slate: an Interview with John Sayles

February 13, 2026

John Sayles at the Miami International Book Fair. Photo: Rodrigo Fernández. CC BY-SA 3.0

The novels of John Sayles encompass a wide swath of American history. Since the wide swath of American history is replete with one injustice after another, those are front and center in Sayles’s fiction.

Crucible, his latest novel, is set in the tumultuous, violent Detroit of the 1920s to World War II. It is a mix of real figures—including Henry Ford, Diego Rivera, Joe Louis, and Ford’s ruthless majordomo/enforcer Harry Bennett—and a multi-ethnic array of fictional characters, drawn from the city’s struggling working class. To describe a book as a sprawling canvas is a cliché, but Crucible is just that—a sprawling canvas that, among other loci, looks at Henry Ford’s grandiose, ill-fated scheme to launch his own rubber-producing empire in the Brazilian Amazon. This new novel, like Sayles’s other work, manages to artfully weave together a host of themes and characters. His writing is a vital piece of the literary landscape.

RK: You’ve said: “History is great because someone has already worked out a plot and a timeline for you.” Is that your main impetus for writing historical fiction?

John Sayles: I got to go to college and I never took a history course. It was something I discovered later. The official story was usually pretty one-note: good guys and bad guys, depending on who wrote it. I realized that there was a better story–a more complex and interesting human story–if you dug a little bit.

One of the things that I read in college on my own was [Dee Brown’s] Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. Every chapter is a different confrontation between an Indian nation and the white people who are moving west. And I realized: Wait a minute. I’ve seen this movie! I’ve seen this movie—Charles Bronson or Jeff Chandler played the Indian! Not only had I seen the movie, but I realized that Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee was a better story. Why didn’t they tell this story in the movies? It’s much more two-sided–it’s at least two sides, maybe more than that and with more complexity in it. It’s a much more interesting story than the one that they told. That’s pretty much been my experience with historical stuff.

With Crucible, I knew some headline things about Detroit and about Henry Ford in this period, but then when I started looking into what happened in that world between 1927 and 1942, there were all these incidents that I had no idea about. I figured, Join the club! There are a lot of people who don’t know about this. And this is a really interesting, complex thing on all sides.

RK: The list of things I didn’t know goes on and on, including Ford’s Brazil project and the fact that there was the Klan in Detroit.

JS: And the [white supremacist] Black Legion. There’s a movie with Humphrey Bogart about a guy who gets sucked into this outfit. [Black Legion, 1937]

RK: Besides being a fount of anti-Semitism, Henry Ford comes across as really bizarre. He doesn’t fit the criteria of a straight-out robber baron; he’s a paternalistic crackpot.

JS: It’s an interesting thing to write about. Ford was iconic in his day. At one point he was known as “America’s favorite tycoon.” He was kind of a holdover in that by 1927 there weren’t that many guys who owned the company lock, stock, and barrel. There were no stockholders in the Ford Motor Company. He owned about 52 percent of the stock and his son Edsel was given 48 percent. And it was going to be handed over to Edsel. So he had that kind of power. If he said that he would close his factories if the workers unionized, he would and he could do it.

On the other hand, he didn’t care about money that much. He had this feeling that he had been touched by a higher power and he was a vessel to improve peoples’ lives. There was a lot of frustration: Why aren’t people following what I’m telling them? This is how they should live and everything would be fine. He rented an ocean liner during World War I, sailing to Europe with a bunch of peaceniks and antiwar people and said, “Here I am, Germany, France, Great Britain—come and talk to me and I’ll solve all your problems. You don’t have to be killing each other.” Nobody wanted to talk to him. He was startled and came back on the ocean liner with his tail between his legs.

There were some very good things about him. He decided he was going to pay his workers twice as much as everybody else so they could afford to buy a Model T. He said that if Black workers were doing the same work, he was going to pay them the same as white workers. Nobody else was doing that in Detroit or anywhere else. On the other hand, he was ignorant. He was a guy who grew up on a farm and he’d never met anyone Jewish in his life—and it’s not like he was alone, especially in Detroit, with Father Coughlin on the radio. Or in the United States as a whole, where Catholics were still considered suspicious. Ford had a lot of the prejudices of the day. He had never met any of these people and had all these crazy ideas about them. He’s a very complex character. And then the thing I really didn’t know about, which I got interested in, is this terrible, tragic relationship between him and his son. Everything you read said that people really liked Edsel. He was a good guy; he was actually pretty artistic. He was a good designer and was behind the designs of some of the nicer looking Ford cars. I’m sure he was rolling in his grave when they put out the Edsel car! The ugliest thing ever and they put his name on it! Henry Ford thought, My son is weak. He grew up as a rich kid. I’ve gotta toughen him up and treat him like hell.

else so they could afford to buy a Model T. He said that if Black workers were doing the same work, he was going to pay them the same as white workers. Nobody else was doing that in Detroit or anywhere else. On the other hand, he was ignorant. He was a guy who grew up on a farm and he’d never met anyone Jewish in his life—and it’s not like he was alone, especially in Detroit, with Father Coughlin on the radio. Or in the United States as a whole, where Catholics were still considered suspicious. Ford had a lot of the prejudices of the day. He had never met any of these people and had all these crazy ideas about them. He’s a very complex character. And then the thing I really didn’t know about, which I got interested in, is this terrible, tragic relationship between him and his son. Everything you read said that people really liked Edsel. He was a good guy; he was actually pretty artistic. He was a good designer and was behind the designs of some of the nicer looking Ford cars. I’m sure he was rolling in his grave when they put out the Edsel car! The ugliest thing ever and they put his name on it! Henry Ford thought, My son is weak. He grew up as a rich kid. I’ve gotta toughen him up and treat him like hell.

RK: There’s a lot of humor in the book, which is a difficult perch and very effective. Harry Bennett, for example, is funny. Bennett is a complete monster—but he’s funny. And I felt sort of guilty for thinking that. You’re obviously dealing with some very heavy topics, but there’s humor throughout.

JS: Bennett was a pretty good painter and he played several musical instruments. He was very charismatic in his way. He could sit down with labor union guys and mobsters and sports people. That’s part of why Ford hired him: This guy’s such a great storyteller and such a tough little guy—he’s exactly what I need at my factory to keep people in line. He doesn’t take a step backward. Ford met him while Harry Bennett was having a fistfight on the street with a couple sailors and he kind of held his own. Henry Ford took him for a drink and they got talking and he gave him a job and he was good at it. Ford kept moving him up and up and up and Harry Bennett just kept taking more and more and more. He was entertaining.

Humor is part of how Americans deal with a bad situation. Some of the funnier thirties movies were made in the depths of the Depression. There were some very funny movies made at that time. One thing to consider when you’re writing a character is: Does this character have a sense of humor? [The fictional character] Rosa Schimmel, who’s the young radical, really doesn’t—she’s a very serious Communist at first. But some of the scenes that’s she’s in are funny because of the situation.

RK: Reading Crucible, you can’t help notice the parallels between now and then. I’m wondering how conscious you were of that or how much you crafted the book to reflect that.

JS: I was aware generally. I wrote this about two years ago. Elon Musk was just making automobiles. He was just some guy people didn’t know much about and he was sort of a wonder boy who was making a new kind of car that sounded like, “Oh, that would be good for the environment. It won’t be burning gasoline.” He caught up to the book in a way.

Our history doesn’t start with a blank slate. Nobody starts with a blank slate. You’re born into the world, you’re a certain class, you’re a certain color, you’re a certain sex—that may change during your life! You’ve got a lot of history that you’re hauling and you’re not even conscious yet.

The Civil War’s not over. We thought, Finally they’re not flying the Stars and Bars anymore and we’ve taken those statues down and we’re starting to tell the real story. And then Trump gets in and says, Oh, hold it. We’re erasing what you just did. We’re putting it back to what it was around 1920. That’s the history that they want Americans to learn and to believe about themselves.

RK: Who have been some of your literary inspirations?

JS: I was reading kids’ books at the same times that I would pick up a paperback that my parents might have around. And I tried to figure out what was going on. Sometimes I would really like the story, especially if it had been made into a movie, because I could imagine the people in the movie in it.

I remember—really early on—reading [Herman Wouk’s] The Caine Mutiny. Nelson Algren was a guy that I discovered fairly early. I read Elmore Leonard before he got well-known. I read all his westerns—they were westerns and they were a little more interesting and had a little more going on with them. Chester Himes—I just picked up If He Hollers Let Him Go and it was—wow! Los Angeles during World War II! And I searched out his other books. A lot of Eudora Welty’s short stories. I eventually read a lot of Faulkner.

What I did instead of taking history courses or even going to classes when I was in high school, I would read three or four novels a week. I would go to the library and I started in the A’s. There had been all these American authors that I’d heard of, but these books had not been available to me. So luckily Mark Twain was under Clemens. And I think I got up to about M or N by the time I graduated. I did read some Philip Roth because he was very hot at the time. Kurt Vonnegut was very hot at that time. But really, it was catch-as-catch-can. In college, I took one English course, a freshman English course and I really didn’t like the way it was being taught. I wasn’t a literature or an English major; I was a psych major.

It’s only been in the last couple years that I’ve started to read classic French, Russian, and British literature; Dickens and people like that. Certainly for [his novel] Jamie MacGillivray I read some Dickens and Smollett and Fielding. I’m still catching up in a lot of ways.

RK: What’s next for you?

JS: I’ve written a novel called Gods of Gotham. It’s already done. It’s set in New York City between 1949 and 1951—a much shorter time period—and it’s a little bit of On the Waterfront and a little bit of West Side Story; the Puerto Ricans are starting to show up. It’s got a lot about corruption; the CCNY point-shaving scandal is one of the centerpieces of it. It’s also about the beginning of television becoming a factor in American life. Because at first not that many people had TV sets and there were four networks. And one of them—the DuMont network–their studio was a showroom at Wanamaker’s department store in New York.

And then the Kefauver Committee happened and everybody wanted to see mobsters on TV. We’d been hearing about these people and they’re bringing them in! And they’re bringing in big-city mayors and senators and stuff like that to ask them point-blank about corruption. In New York City, theaters closed; bars were full and it wasn’t the Friday night fights. All of a sudden, TV became not just an entertainment factor, but also a political factor. That’s woven into the book. Not quite as many characters as Crucible!

RK: How do you write socially conscious fiction in a really horrible time? I assume this implies there’s an element of hope.

JS: Nothing surprises me anymore. My poor father went through World War II and went Trump first got elected, he said, “I thought we were making progress.” And he was really depressed until Trump was out. He was very glad to see him defeated the second time, but then there was that attack on the Capitol. He was 96 by that point and he said, “I think I’m done. I’m disappointed in the American people.” And that was my feeling with the second election.

I think an important thing is the cultural conversation. Most of my friends don’t even read fiction, so it’s not like I think there’s a huge audience for what I’m doing, but it is a part of the conversation. And unless you keep that conversation going, it’s like democracy dies in darkness. The Washington Post is still putting that on their masthead, but they’re part of the problem now.

It’s almost a responsibility, in my way—while I can still do this and get something published—putting something into the world that makes people think about what’s going on around them.

No comments:

Post a Comment