FULL STORY

Moon (stock image).

Credit: © taffpixture / stock.adobe.com

NASA's Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) has confirmed, for the first time, water on the sunlit surface of the Moon. This discovery indicates that water may be distributed across the lunar surface, and not limited to cold, shadowed places.

SOFIA has detected water molecules (H2O) in Clavius Crater, one of the largest craters visible from Earth, located in the Moon's southern hemisphere. Previous observations of the Moon's surface detected some form of hydrogen, but were unable to distinguish between water and its close chemical relative, hydroxyl (OH). Data from this location reveal water in concentrations of 100 to 412 parts per million -- roughly equivalent to a 12-ounce bottle of water -- trapped in a cubic meter of soil spread across the lunar surface. The results are published in the latest issue of Nature Astronomy.

"We had indications that H2O -- the familiar water we know -- might be present on the sunlit side of the Moon," said Paul Hertz, director of the Astrophysics Division in the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. "Now we know it is there. This discovery challenges our understanding of the lunar surface and raises intriguing questions about resources relevant for deep space exploration."

As a comparison, the Sahara desert has 100 times the amount of water than what SOFIA detected in the lunar soil. Despite the small amounts, the discovery raises new questions about how water is created and how it persists on the harsh, airless lunar surface.

Water is a precious resource in deep space and a key ingredient of life as we know it. Whether the water SOFIA found is easily accessible for use as a resource remains to be determined. Under NASA's Artemis program, the agency is eager to learn all it can about the presence of water on the Moon in advance of sending the first woman and next man to the lunar surface in 2024 and establishing a sustainable human presence there by the end of the decade.

SOFIA's results build on years of previous research examining the presence of water on the Moon. When the Apollo astronauts first returned from the Moon in 1969, it was thought to be completely dry. Orbital and impactor missions over the past 20 years, such as NASA's Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite, confirmed ice in permanently shadowed craters around the Moon's poles. Meanwhile, several spacecraft -- including the Cassini mission and Deep Impact comet mission, as well as the Indian Space Research Organization's Chandrayaan-1 mission -- and NASA's ground-based Infrared Telescope Facility, looked broadly across the lunar surface and found evidence of hydration in sunnier regions. Yet those missions were unable to definitively distinguish the form in which it was present -- either H2O or OH.

"Prior to the SOFIA observations, we knew there was some kind of hydration," said Casey Honniball, the lead author who published the results from her graduate thesis work at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa in Honolulu. "But we didn't know how much, if any, was actually water molecules -- like we drink every day -- or something more like drain cleaner."

SOFIA offered a new means of looking at the Moon. Flying at altitudes of up to 45,000 feet, this modified Boeing 747SP jetliner with a 106-inch diameter telescope reaches above 99% of the water vapor in Earth's atmosphere to get a clearer view of the infrared universe. Using its Faint Object infraRed CAmera for the SOFIA Telescope (FORCAST), SOFIA was able to pick up the specific wavelength unique to water molecules, at 6.1 microns, and discovered a relatively surprising concentration in sunny Clavius Crater.

"Without a thick atmosphere, water on the sunlit lunar surface should just be lost to space," said Honniball, who is now a postdoctoral fellow at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. "Yet somehow we're seeing it. Something is generating the water, and something must be trapping it there."

Several forces could be at play in the delivery or creation of this water. Micrometeorites raining down on the lunar surface, carrying small amounts of water, could deposit the water on the lunar surface upon impact. Another possibility is there could be a two-step process whereby the Sun's solar wind delivers hydrogen to the lunar surface and causes a chemical reaction with oxygen-bearing minerals in the soil to create hydroxyl. Meanwhile, radiation from the bombardment of micrometeorites could be transforming that hydroxyl into water.

How the water then gets stored -- making it possible to accumulate -- also raises some intriguing questions. The water could be trapped into tiny beadlike structures in the soil that form out of the high heat created by micrometeorite impacts. Another possibility is that the water could be hidden between grains of lunar soil and sheltered from the sunlight -- potentially making it a bit more accessible than water trapped in beadlike structures.

For a mission designed to look at distant, dim objects such as black holes, star clusters, and galaxies, SOFIA's spotlight on Earth's nearest and brightest neighbor was a departure from business as usual. The telescope operators typically use a guide camera to track stars, keeping the telescope locked steadily on its observing target. But the Moon is so close and bright that it fills the guide camera's entire field of view. With no stars visible, it was unclear if the telescope could reliably track the Moon. To determine this, in August 2018, the operators decided to try a test observation.

"It was, in fact, the first time SOFIA has looked at the Moon, and we weren't even completely sure if we would get reliable data, but questions about the Moon's water compelled us to try," said Naseem Rangwala, SOFIA's project scientist at NASA's Ames Research Center in California's Silicon Valley. "It's incredible that this discovery came out of what was essentially a test, and now that we know we can do this, we're planning more flights to do more observations."

SOFIA's follow-up flights will look for water in additional sunlit locations and during different lunar phases to learn more about how the water is produced, stored, and moved across the Moon. The data will add to the work of future Moon missions, such as NASA's Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER), to create the first water resource maps of the Moon for future human space exploration.

In the same issue of Nature Astronomy, scientists have published a paper using theoretical models and NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter data, pointing out that water could be trapped in small shadows, where temperatures stay below freezing, across more of the Moon than currently expected. The results can be found here.

"Water is a valuable resource, for both scientific purposes and for use by our explorers," said Jacob Bleacher, chief exploration scientist for NASA's Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate. "If we can use the resources at the Moon, then we can carry less water and more equipment to help enable new scientific discoveries."

SOFIA is a joint project of NASA and the German Aerospace Center. Ames manages the SOFIA program, science, and mission operations in cooperation with the Universities Space Research Association, headquartered in Columbia, Maryland, and the German SOFIA Institute at the University of Stuttgart. The aircraft is maintained and operated by NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center Building 703, in Palmdale, California.

Learn more about SOFIA at: https://www.nasa.gov/sofia

Related Multimedia:

YouTube video: SOFIA Discovers Water on a Sunlit Surface of the Moon

Journal Reference:

C. I. Honniball, P. G. Lucey, S. Li, S. Shenoy, T. M. Orlando, C. A. Hibbitts, D. M. Hurley, W. M. Farrell. Molecular water detected on the sunlit Moon by SOFIA. Nature Astronomy, Oct. 26, 2020; DOI: 10.1038/s41550-020-01222-x

Did Arthur C. Clarke call it right? Water spotted in Moon's sunlit Clavius crater by NASA telescope

Fly me to the Moon, let me swim among the stars

Water molecules have been detected in soil in one of the Moon's largest sunlit craters, NASA announced on Monday, which means permanent bases on the natural satellite may be potentially a lot easier to support.

The discovery was made using a telescope onboard NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) – a modified Boeing 747 capable of flying 45,000 feet above our planet. The airborne 'scope spied what may well be water in the Clavius crater, which is visible from Earth, located in the southern hemisphere, and, coincidentally, the site of mankind's first Moon base in Arthur C. Clarke's classic science fiction novel 2001.

“We had indications that H2O – the familiar water we know – might be present on the sunlit side of the Moon,” said Paul Hertz, director of NASA’s Astrophysics Division in the Science Mission Directorate.

“Now we know it is there. This discovery challenges our understanding of the lunar surface and raises intriguing questions about resources relevant for deep space exploration.”

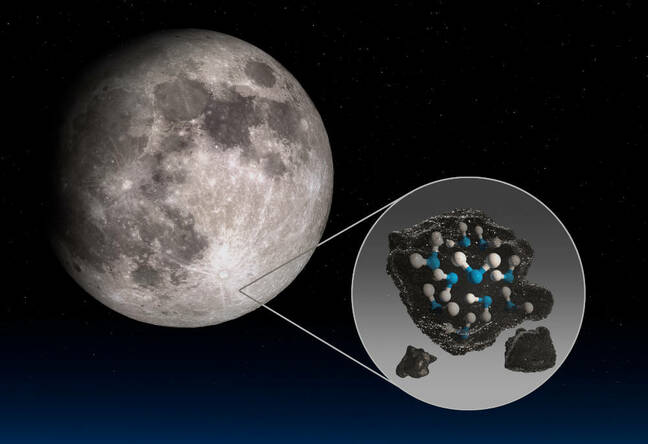

An illustration of water molecules in lunar beads and the location of the crater in the southern hemisphere of the Moon ... Source: NASA/Daniel Rutter

NASA doesn’t know exactly how much water in total is present in the crater. Initial readings, published in Nature Astronomy, show the Clavius regolith contains about 100 to 412 parts per million of water – that’s roughly a 12-ounce bottle of water, or about 355 ml of the liquid, per cubic metre of lunar soil.

In other words, the Moon is still pretty dry. The Sahara desert, for instance, contains 100 times more water than the amount found in the Clavius crater.

The water molecules are spread so thinly that they do not form liquid water or solid ice, said Casey Honniball, a postdoctoral fellow at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, during a press conference today. Instead, they are trapped within tiny beads, each one measuring about the size of a pencil tip. She believes the water is formed from solar wind and micrometeorite impacts.

Radiation from the Sun frees hydroxy (OH) from chemical compounds in the lunar soil, and tiny meteorite impacts provide the heat needed to merge two hydroxy particles to ultimately form water. This energy also melts surrounding material to form the glass beads that act as a protective casing to allow the water molecules to survive and persist despite the Moon’s lack of atmosphere.

Everything's falling apart. The Moon is slowly rusting up – and it's probably Earth's fault

READ MOREScientists know that some water is tucked away as icy deposits, known as cold traps, in the Moon's polar regions that are permanently covered in shadow. This is the first time water has been found in sunlit areas.

"Water is critical for deep space exploration,” Jacob Bleacher, chief exploration scientist at NASA’s Advanced Exploration Systems Division, told reporters during the press briefing. “It can be turned into oxygen to breathe, water to drink, or be used for fuel supply.”

The American space agency hopes to land the first woman and next man on the Moon by 2024, and wants to eventually set up a lunar base [PDF]. If water can be extracted from the surface, it’ll make living on the natural satellite much easier, and provide a way for future generations of astronauts to restock and refuel on their way to more distant locations, such as Mars.

But the idea is purely speculative at the moment. Bleacher said scientists don’t yet know how accessible the water is, though finding it in sunlit areas is good news for upcoming lunar missions.

Naseem Rangwala, SOFIA’s project scientist at NASA's Ames Research Center, said the data was recorded when its 747 flew over Nevada in 2018. It was the first time the airborne telescope had been directed at the Moon. The results are only now being released after months of analysis.

The team is planning more observations using SOFIA next year. In order to work out if the water is accessible, NASA will need to send spacecraft to collect and study samples of the lunar surface. Its next Moon rover, the Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER), is designed to hunt for water at the Moon's south pole and is expected to launch in 2023.

Interestingly, in a separate study also published on Monday, a group of researchers at the University of Colorado predicted that the total area of cold traps on the Moon is some 15,000 square miles, double the amount in previous estimates. ®

Water is present in more places but won't be equally accessible.

JOHN TIMMER - 10/26/2020, 2:39 PM

Enlarge / The instrument used to detect the water flies on a 747.

NASA/Jim Ross

Despite its proximity to a very blue planet, the Earth's Moon appeared to be completely dry, with samples returned by the Apollo missions being nearly devoid of water. But in recent years, a number of studies have turned up what appears to be water in some locations on the Moon, although the evidence wasn't always decisive.

Today, NASA is announcing that it has used an airborne observatory to spot clear indications of water in unexpected places. But the water may be in a form that makes accessing it much harder. Separately, an analysis of spots where water could be easier to reach indicates that there's more potential reservoirs than we'd previously suspected.

Up in the air

With no atmosphere and low gravity, the Moon can't hang on to water on its surface. The first time that sunlight heats lunar water up, it will form a vapor and eventually escape into space. But there are regions on the Moon, primarily near the poles, that are permanently shadowed. There, temperatures remain perpetually low, and ice can survive indefinitely. And, to test this possibility, NASA crashed some hardware into a shady area near the Moon's south pole and found water vapor amidst the debris.

In fact, water liberated from elsewhere on the Moon can condense there before it escapes into space, potentially creating a growing pile of ice. Since water is going to be delivered by impacts with asteroids and cometary material, it's likely that this is an ongoing process.

But we wouldn't expect this to be happening in any areas exposed to sunlight. There, any water should be heated enough to drive it into the atmosphere, which would explain why samples returned from the Apollo missions show little water.

But there was a certain ambiguity in the data. Studies had indicated that some water-like material was present but couldn't differentiate between water and a hydroxyl group (OH), which could exist in some minerals. So, we weren't really sure what we were seeing there.

To figure this out, NASA turned to an infrared observatory that it's stuck in the back-end of a 747 with a hole cut out of the side. Known as the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy or SOFIA, the 747 brings the hardware up above much of the atmosphere. From there, there are far fewer molecules that would happily absorb some of the infrared light that the telescopes on SOFIA are designed to observe.

One of SOFIA's instruments is sensitive to wavelengths in the area of six micrometers (the Faint Object infraRed CAmera for the SOFIA Telescope, or FORCAST). And that's critical because, while water can absorb and emit at this wavelength, hydroxyl groups cannot. So, anything detected here is definitively water.

Where’s the water?

The researchers looked at two regions of the Moon, one equatorial and one near a pole. This allowed them to use the equatorial site, which gets more sunlight and is therefore less likely to have water, as a control. The polar region, more likely to contain water, was the experimental. And it had a clear, strong signal corresponding to water. Nearly all of the areas imaged saw the water signal with a significance of anywhere from two sigma, and 20 percent of them exceeded four sigma. (For the Moon, the instrument could resolve patches of surface that are 1.5 x 5km.)

The authors of the new paper estimate the abundance of water as ranging from 100 to 400 micrograms per gram of lunar material. In a press conference, however, NASA decided to give an approachable value by mixing units: it's the equivalent of each cubic meter of Moon material having a 12 ounce bottle of water in it, on average.

And this is weird. The sunlight the area sees should be enough to cause any water to be cooked off rapidly. How is the water still there?

The authors' proposal—and it's just a hypothesis at this point—is that the water has been encased in glass. Rather than envisioning a literal 12 ounce glass bottle, you should be thinking of the disordered material that's formed by impacts. Some of the impacts on the Moon will come from water-containing materials, and that water will be vaporized by the impact. As will some of the rock and other materials, although they'll condense back to liquid quickly. As that rocky liquid cools off to form a disordered, glassy solid, it'll trap some of the water vapor.

Once trapped inside some glassy rock, the water will be impervious to the heating and cooling cycles that would normally drive the water back off the Moon's surface, which is why it's persisting at a sunny site on the lunar surface.

It also means that getting at the water will be a lot harder. Plenty of ideas about future lunar activities involve gathering water on the surface. But, if getting the water involves grinding down tiny pellets of glass, it may be significantly more trouble.

In the shade

But again, the focus on lunar water hasn't been in the sunny regions. Instead, the focus has been on the sites where shade might allow water to condense and form ice. And that's where the second paper comes in; it basically makes a catalog of all the potential sites on the Moon that are cold enough for ice to remain stable. And we mean all, even going down to considering rough surfaces that may create shady regions as small as one centimeter.

ARS VIDEO

US Navy Gets an Italian Accent

The researchers figure out the location of large sites by looking through the images of the lunar surface and creating a 3D model that gets them the areas that would be shaded under all circumstances. For lower-volume areas, they examine images of the Moon's surface and figure out what percentage of that surface would end up shaded. They then model the diffusion of heat from the Sun-exposed sections and figure out which areas will remain cool enough to retain ice in the vacuum.

And, well, there's no shortage of potential places where water could exist without being encased in glass. The northern polar region has lots of regions with cold traps ranging from a meter up to 10 kilometers. But the southern polar region has far more that are over 10km in size. All told, this adds up to about 40,000 square kilometers of the Moon's surface that could hold water ice.

This doesn't mean that all that water is there. Some of it clearly is, based on NASA's earlier probe-crashing "experiment" that liberated some water vapor from the Moon's surface. But how much remains completely unclear. And whether it's in large, easily accessible ice deposits will remain an unknown until we get hardware to one of the locations we expect to host a large deposit.

Nature Astronomy, 2020. DOI: 10.1038/s41550-020-01222-x, 10.1038/s41550-020-1198-9x (About DOIs).

No comments:

Post a Comment