Despite global ambitions, Elon Musk’s Starlink struggles to reach users outside North America and Europe.

Nina Lyashonok/Ukrinform/Future Publishing/Getty Images

By MEAGHAN TOBIN

28 APRIL 2022

Last year, Sarfaraz Hassan, the chief technology officer at an adventure tourism startup in India’s northeastern Assam state, signed up to receive a Starlink unit from SpaceX. Hassan thought Elon Musk’s satellite internet service could help his company, Encamp, entice digital nomads to work from the rugged foothills of the eastern Himalayas, where fewer than 40% of people have access to broadband. Then, in early January, Starlink announced that preorders in India were being refunded until the company received license to operate in the country. After months of waiting, Hassan recently got his $99 deposit (about 7,500 rupees) back.

Hassan is one of the half a million people worldwide who have signed up to receive Elon Musk’s Starlink service but are still waiting for access. In India, where Starlink was supposed to arrive this month, SpaceX had planned to deploy 200,000 dishes across the country by the end of this year. Instead, the company has had to refund its waiting list at the direction of the Indian government, leaving thousands waiting for connectivity. (The Indian telecomms regulator had warned the public late last year not to pay for equipment before the company had a license.)

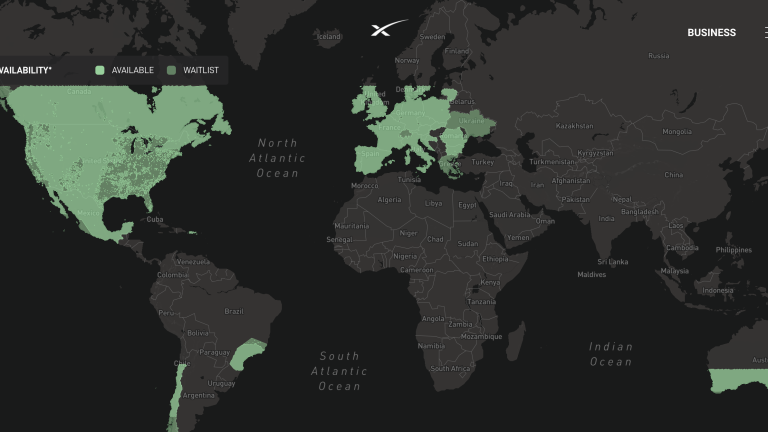

In June 2021, Elon Musk claimed that Starlink would span the globe within months. But nearly a year later, the service has, with a few exceptions, been exclusively made available in North America, Europe, and Australia. The issue of refunds to the waiting list in India is the latest in a series of stumbling blocks that have prevented Starlink from bringing the internet to the hardest-to-reach places on Earth.

SpaceX has pushed back rollouts in massive markets like South Africa, where, at the end of last year, the expected date for Starlink service to become available was delayed from 2022 to 2023, with no explanation. Last month, Starlink surpassed 250,000 subscribers across 25 countries. But according to Cloudflare and self-reported statistics on Reddit, nearly 80% of users to date are located in North America, with another 18% in Australia, New Zealand, and Europe. Just 2% of Starlink users live in the rest of the world. Although many of the delays come down to regulatory challenges, it’s also unclear whether the service is prioritizing existing markets or growing new ones.

Starlink’s current coverage area.https://www.starlink.com/map

Although Starlink had a notably successful deployment in Ukraine in late February, the service was already being set up in the country at the time of the Russian invasion, and the effort was carried off with millions of dollars in support from the U.S. government. In Ukraine, SpaceX issued an update to enable mobile roaming, giving users the ability to access the internet from the road, even from a moving vehicle. While this update helps users living in a war zone, it also entrenches Starlink’s appeal among one of its main user bases in the West: digital nomads who want to use the service to work remotely and stream Netflix from campers, RVs, and boats.

Korath Mathew, a Delhi-based independent consultant who has worked on government smart city projects across India and Kenya, told Rest of World that he hoped that the March mobility update was a positive indicator that Starlink service might soon expand services. “I was thinking that it’s suddenly going to come in [to India], because so many people had signed up,” Mathew told Rest of World. “Even portability is available now. You can travel across the whole U.S., while moving. This gave us a hope that access could be implemented [here] in rural areas.” But the update did not make service available in India. SpaceX did not respond to Rest of World’s request for comment.

Mathew says he doesn’t understand why the government hasn’t granted Starlink license to operate in India. “You have satellite phones in India, you have geosatellite communication,” said Mathew, referring to traditional satellites. “It just doesn’t make any sense not to broaden it out to low earth orbit satellites like Starlink.”

Encamp founder Ratan Kumar said his startup had planned to use its Starlink equipment to connect neighboring communities and schoolchildren. “We were very excited when we heard Starlink is coming into India,” Kumar told Rest of World. “We were like, we’re going to have one dish in every location where we operate. Obviously, that didn’t work out.”

Mike Puchol, who runs the website starlink.sx, which maps the global availability of Starlink service based on open-source data, had a similar vision for how Starlink could be used to distribute connectivity in Kenya, where he also runs an internet service startup called Poa! internet. If Starlink were available in Kenya, said Puchol, it could function as backhaul for the country’s minimal fiber infrastructure. Puchol said that given current prices and internet speeds available in much of Kenya, as many as 100 people could conceivably use a terminal at once, at a cost as low as a dollar a month per person.

When the island nation Tonga was cut off from the internet following the eruption of a massive underwater volcano earlier this year, Starlink sent 50 terminals to the country. By the time they arrived, the main internet cable had been reconnected, so the Starlink equipment was sent to support outer islands, where international aid groups had already coordinated to send Broadband Global Area Network (BGAN) terminals and satellite phones. The head of state-backed Tonga Cable Ltd., Samisi Panuve, told Rest of World that while a few terminals had been sent to “outer island government departments and communities and some public areas,” his company hadn’t found a use for its Starlink equipment.

“We were like, we’re going to have one dish in every location where we operate. Obviously, that didn’t work out.”

Part of the reason Starlink has failed to expand outside the West has been regulatory challenges. While Starlink has been welcomed by regulators in places like Chile, in other countries, regulators face pushback from powerful domestic telecommunications lobbies. In India, Puchol pointed out that Bharti, which operates local broadband provider Airtel, has a stake in one of Starlink’s direct competitors, OneWeb. In addition, many regulators aren’t used to moving at the speed of Silicon Valley, added Puchol. “I think Starlink there went too fast and then got the door slammed in their face.”

Gaining regulatory approval to access new markets is Starlink’s biggest global challenge, said Jose Del Rosario, a Manila-based consultant at satellite industry firm Northern Sky Research. But mobile roaming will greatly increase its commercial appeal. “A few thousand aircrafts and hundreds of cruise ships can close the business case,” said Del Rosario.

A private yacht captain based in the Caribbean told Rest of World that he started using Starlink last year because the price was so much lower than the up to $6,000 per month he had paid for commercial internet on the open sea. “If [Musk] starts selling it to commercial airlines, boats, trucks, and buses, he is going to make a lot of money,” the captain told Rest of World. “His plans are likely much bigger than helping Ukraine and people in remote locations.”

Meanwhile, Starlink service has continued to expand in some markets. In January, Starlink reported 145,000 users, and subscriptions nearly doubled that number just two months later. And while SpaceX has launched dozens of satellites to build out its constellation, it has also inked a deal to offer in-flight Wi-Fi on American air carrier Hawaii Airlines.

For his part, Kumar is still hopeful that Starlink will become available in India soon. He credits Musk as an entrepreneurial inspiration “to keep the same grit and determination in whatever small thing we are trying to achieve in our own career.” But if one of Starlink’s competitors, like Amazon’s Project Kuiper or Softbank-backed OneWeb, succeeds in getting satellite service to his area first, he won’t hold out for Musk. “We expect Starlink to come over, but if that doesn’t happen, we’ll do it with an Indian network, whatever is possible,” Kumar said. “The Indian market is a tough nut to crack for an organization which is coming from outside. There are hurdles, but the market size cannot be ignored.”

Although Starlink had a notably successful deployment in Ukraine in late February, the service was already being set up in the country at the time of the Russian invasion, and the effort was carried off with millions of dollars in support from the U.S. government. In Ukraine, SpaceX issued an update to enable mobile roaming, giving users the ability to access the internet from the road, even from a moving vehicle. While this update helps users living in a war zone, it also entrenches Starlink’s appeal among one of its main user bases in the West: digital nomads who want to use the service to work remotely and stream Netflix from campers, RVs, and boats.

Korath Mathew, a Delhi-based independent consultant who has worked on government smart city projects across India and Kenya, told Rest of World that he hoped that the March mobility update was a positive indicator that Starlink service might soon expand services. “I was thinking that it’s suddenly going to come in [to India], because so many people had signed up,” Mathew told Rest of World. “Even portability is available now. You can travel across the whole U.S., while moving. This gave us a hope that access could be implemented [here] in rural areas.” But the update did not make service available in India. SpaceX did not respond to Rest of World’s request for comment.

Mathew says he doesn’t understand why the government hasn’t granted Starlink license to operate in India. “You have satellite phones in India, you have geosatellite communication,” said Mathew, referring to traditional satellites. “It just doesn’t make any sense not to broaden it out to low earth orbit satellites like Starlink.”

Encamp founder Ratan Kumar said his startup had planned to use its Starlink equipment to connect neighboring communities and schoolchildren. “We were very excited when we heard Starlink is coming into India,” Kumar told Rest of World. “We were like, we’re going to have one dish in every location where we operate. Obviously, that didn’t work out.”

Mike Puchol, who runs the website starlink.sx, which maps the global availability of Starlink service based on open-source data, had a similar vision for how Starlink could be used to distribute connectivity in Kenya, where he also runs an internet service startup called Poa! internet. If Starlink were available in Kenya, said Puchol, it could function as backhaul for the country’s minimal fiber infrastructure. Puchol said that given current prices and internet speeds available in much of Kenya, as many as 100 people could conceivably use a terminal at once, at a cost as low as a dollar a month per person.

When the island nation Tonga was cut off from the internet following the eruption of a massive underwater volcano earlier this year, Starlink sent 50 terminals to the country. By the time they arrived, the main internet cable had been reconnected, so the Starlink equipment was sent to support outer islands, where international aid groups had already coordinated to send Broadband Global Area Network (BGAN) terminals and satellite phones. The head of state-backed Tonga Cable Ltd., Samisi Panuve, told Rest of World that while a few terminals had been sent to “outer island government departments and communities and some public areas,” his company hadn’t found a use for its Starlink equipment.

“We were like, we’re going to have one dish in every location where we operate. Obviously, that didn’t work out.”

Part of the reason Starlink has failed to expand outside the West has been regulatory challenges. While Starlink has been welcomed by regulators in places like Chile, in other countries, regulators face pushback from powerful domestic telecommunications lobbies. In India, Puchol pointed out that Bharti, which operates local broadband provider Airtel, has a stake in one of Starlink’s direct competitors, OneWeb. In addition, many regulators aren’t used to moving at the speed of Silicon Valley, added Puchol. “I think Starlink there went too fast and then got the door slammed in their face.”

Gaining regulatory approval to access new markets is Starlink’s biggest global challenge, said Jose Del Rosario, a Manila-based consultant at satellite industry firm Northern Sky Research. But mobile roaming will greatly increase its commercial appeal. “A few thousand aircrafts and hundreds of cruise ships can close the business case,” said Del Rosario.

A private yacht captain based in the Caribbean told Rest of World that he started using Starlink last year because the price was so much lower than the up to $6,000 per month he had paid for commercial internet on the open sea. “If [Musk] starts selling it to commercial airlines, boats, trucks, and buses, he is going to make a lot of money,” the captain told Rest of World. “His plans are likely much bigger than helping Ukraine and people in remote locations.”

Meanwhile, Starlink service has continued to expand in some markets. In January, Starlink reported 145,000 users, and subscriptions nearly doubled that number just two months later. And while SpaceX has launched dozens of satellites to build out its constellation, it has also inked a deal to offer in-flight Wi-Fi on American air carrier Hawaii Airlines.

For his part, Kumar is still hopeful that Starlink will become available in India soon. He credits Musk as an entrepreneurial inspiration “to keep the same grit and determination in whatever small thing we are trying to achieve in our own career.” But if one of Starlink’s competitors, like Amazon’s Project Kuiper or Softbank-backed OneWeb, succeeds in getting satellite service to his area first, he won’t hold out for Musk. “We expect Starlink to come over, but if that doesn’t happen, we’ll do it with an Indian network, whatever is possible,” Kumar said. “The Indian market is a tough nut to crack for an organization which is coming from outside. There are hurdles, but the market size cannot be ignored.”

Meaghan Tobin is a reporter at Rest of World.

Masha Borak contributed reporting to this story.

No comments:

Post a Comment