2022/4/26

© Agence France-Presse

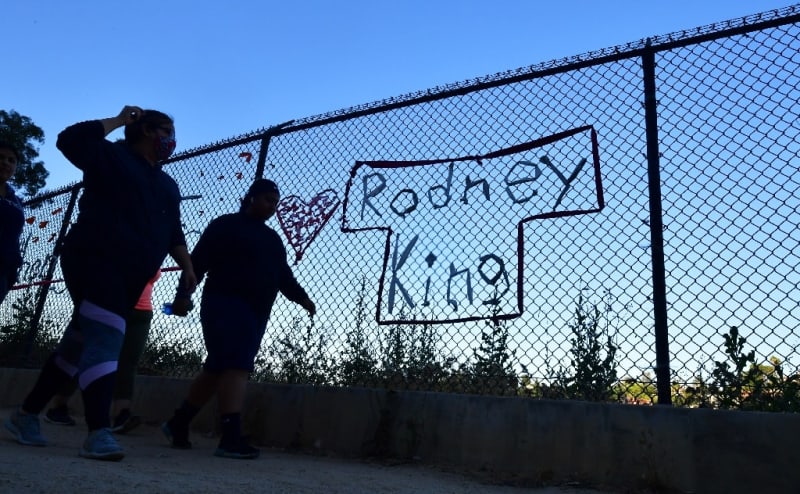

Thirty years ago, Los Angeles erupted in deadly violence after four police officers were acquitted of the savage beating of Rodney King, despite graphic video footage of the attack

Los Angeles (AFP) - A multi-ethnic group of Los Angeles community leaders will gather on Friday, marking 30 years since their city was engulfed in a wave of violence following the acquittal of white police officers for the beating of Rodney King, a Black man.

The deadly 1992 Los Angeles riots inflamed deep-seated tensions across America's second largest city, as fury in the Black community at racial injustice boiled over and Korean-American and other immigrant shopkeepers bore the brunt of the carnage.

"There's nothing romantic, nothing enticing, nothing beautiful about celebrating what happened for those six days," said "J" Edgar Boyd, pastor at First AME, the city's oldest African-American church.

"But what we have agreed to do, is to take the ugliness and the disparities of those things that happened then, and own them for being reality."

Sprawling Los Angeles has long prided itself on being one of the most culturally and ethnically diverse cities on Earth.

But racial groups have often clustered in divided communities, from wealthy white Bel-Air to Black Baldwin Hills and Latino East Los Angeles -- all just a few miles apart.

On April 29, 1992, despite graphic video footage of the beating of King, the closely-watched trial of the four cops ended with verdicts of "not guilty."

That night, violence first broke out in then-predominantly Black South Los Angeles, where many mom-and-pop stores were run by Korean immigrants.

Looting gangs brought violence and arson to Koreatown itself, where gun-wielding Korean vigilantes took to shop roofs to defend their properties, in images beamed around the world.

By the end of the anarchy, around 60 people were dead, 2,000 injured and approximately $1 billion in damages had been wrought -- almost half suffered by Korean-American owners.

The violence was "America's first multi-ethnic riots," said Edward Chang, professor of ethnic studies at University of California, Riverside.

'Poor fighting the poor'

Walking through Koreatown today -- a trendy, sprawling neighborhood whose name belies the fact it is now majority Latino -- it is hard to imagine those apocalyptic scenes 30 years ago.

But in 1992, racial tensions were already simmering because of the fatal shootings of two Black customers by Korean store owners in separate incidents months earlier.

Neither of the killers of Lee Arthur Mitchell and 15-year-old Latasha Harlins spent a day in prison, broiling resentment between communities riven by stark economic and cultural divides.

"It was not necessarily an intent to go after Korean American businesses... the intent was to respond to the lack of justice that was continually perpetuated upon the Black community," said Boyd.

But for many protesters, the perception -- accurate or not -- of Koreans as "absentee shop owners" with no interest in "pouring back into the community part of what they took out" made them easy targets, said Boyd.

According to David Ryu, a teen at the time of the riots who became Los Angeles' first Korean-American councilmember, the violence was less a "Korean-Black conflict" and more "the poor fighting the poor."

Back in the 1990s, Korean-Americans were just the latest group to set up in inner-city Los Angeles, following earlier Jewish, Italian and Eastern European store owners.

Ryu's parents had sold their toy store not long before the building was torched by looters.

"Because they couldn't get mad at white America, or the powers-that-be, they got mad at the person in front of them," said Ryu, drawing a link to the city's Watts Riots of 1965.

This time, "anger was displaced on the Korean-Americans," he said.

'Their American Dream'

According to Chang, viewing US race relations as an "anti-Blackness" or "Black-versus-white" issue is an "East Coast bias" that ignores Los Angeles' complex tapestry.

In 1992, Los Angeles police "decided not to protect and serve the community they were supposed to -- Koreatown was abandoned," recalled Chang.

"Korean immigrants had no choice but to defend their stores. That was their livelihood, that was their American Dream."

For some, there are parallels with recent attacks on Asian-Americans, which have risen during the Covid-19 pandemic.

According to the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, hate crimes against Asian-Americans rose over 300 percent last year.

This Friday, Los Angeles leaders will gather to highlight ties between their communities, including a First AME community service held in a building financed by a Korean bank.

"That's a great milestone. They did it when we could not get other (banks) -- Black or otherwise -- to do it," said Boyd.

"What we're going to do on the 29th is to show the world, and Los Angeles, that we intend to be big enough to mitigate the breaches that took place on that infamous day."

Los Angeles (AFP) - A multi-ethnic group of Los Angeles community leaders will gather on Friday, marking 30 years since their city was engulfed in a wave of violence following the acquittal of white police officers for the beating of Rodney King, a Black man.

The deadly 1992 Los Angeles riots inflamed deep-seated tensions across America's second largest city, as fury in the Black community at racial injustice boiled over and Korean-American and other immigrant shopkeepers bore the brunt of the carnage.

"There's nothing romantic, nothing enticing, nothing beautiful about celebrating what happened for those six days," said "J" Edgar Boyd, pastor at First AME, the city's oldest African-American church.

"But what we have agreed to do, is to take the ugliness and the disparities of those things that happened then, and own them for being reality."

Sprawling Los Angeles has long prided itself on being one of the most culturally and ethnically diverse cities on Earth.

But racial groups have often clustered in divided communities, from wealthy white Bel-Air to Black Baldwin Hills and Latino East Los Angeles -- all just a few miles apart.

On April 29, 1992, despite graphic video footage of the beating of King, the closely-watched trial of the four cops ended with verdicts of "not guilty."

That night, violence first broke out in then-predominantly Black South Los Angeles, where many mom-and-pop stores were run by Korean immigrants.

Looting gangs brought violence and arson to Koreatown itself, where gun-wielding Korean vigilantes took to shop roofs to defend their properties, in images beamed around the world.

By the end of the anarchy, around 60 people were dead, 2,000 injured and approximately $1 billion in damages had been wrought -- almost half suffered by Korean-American owners.

The violence was "America's first multi-ethnic riots," said Edward Chang, professor of ethnic studies at University of California, Riverside.

'Poor fighting the poor'

Walking through Koreatown today -- a trendy, sprawling neighborhood whose name belies the fact it is now majority Latino -- it is hard to imagine those apocalyptic scenes 30 years ago.

But in 1992, racial tensions were already simmering because of the fatal shootings of two Black customers by Korean store owners in separate incidents months earlier.

Neither of the killers of Lee Arthur Mitchell and 15-year-old Latasha Harlins spent a day in prison, broiling resentment between communities riven by stark economic and cultural divides.

"It was not necessarily an intent to go after Korean American businesses... the intent was to respond to the lack of justice that was continually perpetuated upon the Black community," said Boyd.

But for many protesters, the perception -- accurate or not -- of Koreans as "absentee shop owners" with no interest in "pouring back into the community part of what they took out" made them easy targets, said Boyd.

According to David Ryu, a teen at the time of the riots who became Los Angeles' first Korean-American councilmember, the violence was less a "Korean-Black conflict" and more "the poor fighting the poor."

Back in the 1990s, Korean-Americans were just the latest group to set up in inner-city Los Angeles, following earlier Jewish, Italian and Eastern European store owners.

Ryu's parents had sold their toy store not long before the building was torched by looters.

"Because they couldn't get mad at white America, or the powers-that-be, they got mad at the person in front of them," said Ryu, drawing a link to the city's Watts Riots of 1965.

This time, "anger was displaced on the Korean-Americans," he said.

'Their American Dream'

According to Chang, viewing US race relations as an "anti-Blackness" or "Black-versus-white" issue is an "East Coast bias" that ignores Los Angeles' complex tapestry.

In 1992, Los Angeles police "decided not to protect and serve the community they were supposed to -- Koreatown was abandoned," recalled Chang.

"Korean immigrants had no choice but to defend their stores. That was their livelihood, that was their American Dream."

For some, there are parallels with recent attacks on Asian-Americans, which have risen during the Covid-19 pandemic.

According to the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, hate crimes against Asian-Americans rose over 300 percent last year.

This Friday, Los Angeles leaders will gather to highlight ties between their communities, including a First AME community service held in a building financed by a Korean bank.

"That's a great milestone. They did it when we could not get other (banks) -- Black or otherwise -- to do it," said Boyd.

"What we're going to do on the 29th is to show the world, and Los Angeles, that we intend to be big enough to mitigate the breaches that took place on that infamous day."

THE PEASANTS RIOTED AGAINST THE DUTCH , JEWISH, GERMAN, ETC SHOP KEEPERS IN THE MIDDLE AGES, OFTEN SUPPORTED IN THESE POGROMS BY THE LOCAL AUTHORITIES; SUCH AS VLAD TEPES OF TRANSLVANIA (HE IMPALED DUTCH SHOP KEEPERS FOR TAX AVOIDANCE)

No comments:

Post a Comment