A free Palestine is inevitable

Pawel Wargan

On October 7, the Palestinian people broke the nearly 20-year siege of Gaza — the world’s largest open-air prison. In response, the Israeli regime threatened them with extermination. “There will be no electricity, no food, no water, no fuel, everything is closed,” Israel’s Defense Minister said. “We are fighting human animals, and we will act accordingly.” Now, the siege has intensified to genocidal proportions. Hundreds of thousands were internally displaced within Gaza, which has a population of two million people with nowhere to go. The number of dead, likely underreported, rises by the hour. Entire housing blocks are being leveled as terrorized families cower in darkness, cut off from the outside world.

From Washington to Brussels, the leaders of the old colonial powers have been quick to cheer on the violence, while slandering the Palestinian resistance with increasingly-hysterical atrocity propaganda. But to insist, as they do, that the “violence is unprovoked” is to opt for amnesia. The violence — the original violence of the colonizer — has long been weaved into the very geography of colonized Palestine. Its serene landscapes are scarred by walls and mazes, checkpoints and guard towers, outposts and turrets. They sever farmers from farms, traders from trade routes, fishermen from the sea, brothers from sisters. Sometimes, they appear within homes. A group of settlers moved into the house of the el-Kurd family in Sheikh Jarrah, East Jerusalem, severing their garden, living room, and two bedrooms from the rest. The occupied parts of the home, like other zones of occupation across Palestine, are an image of neglect. Everywhere, settlers make the land unlivable to those who seek to return.

Sheikh Jarrah. Photo: Pawel Wargan

The silent war

When we visited Palestine in May as part of an international brigade organized by the Progressive International in collaboration with the International Peoples’ Assembly, we saw that violence unfold across the topography of the occupation. From the Old City of East Jerusalem, past the Al-Aqsa Mosque, we descended a steep hill. We passed the so-called City of David — a settler encroachment where, under the guise of archeological excavations for traces of ancient Judaic architecture that largely do not exist, the occupation forces uprooted Palestinian orchards and enclosed their land. We arrived in Silwan. The enclave is home to over 65,000 Palestinians. There, thousands of houses face demolition for not having the right permits — and many have already been turned to rubble. Families are sometimes given the opportunity to bail their homes out — to pay a ransom for them to remain standing. But, the bulldozers still come. Then, the evicted family receives a bill for the soldiers and dogs that forced them from their home — and for the machines that tore it down. Later, the settlers arrive, always flanked by armed guards. “In Gaza you see the bombs. In the West Bank, the martyrs. Here, there is a silent war,” Kutaybah Odeh, a local community organizer, told us.

Still, the people of Silwan organize to resist this silent war. When the bulldozers come, they rally to defend the families whose gruesome turn had come. The Al-Bustan Community Center that Odeh runs has become a thriving heart of the community. There, you find simple, defiant joys: trumpets and drums for the marching band; a large tatami mat and, outside, a performance stage and playground — signs of normality and resistance in a site of erasure. All around, the narrow alleys of the neighborhood are adorned with trees, tiles, and drawings. “The occupation authorities tell us that they will destroy our homes because they are unfit to live in,” Odeh said. “So we show them that we live in paradise.”

Silwan. Photo: Pawel Wargan

The occupation within the occupation

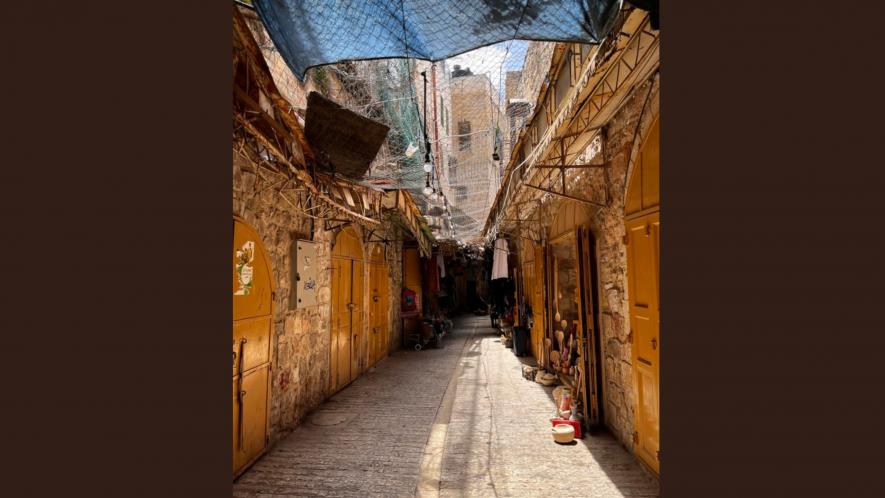

From the frontline of Odeh’s “silent war”, we traveled to Hebron, or its Indigenous name Al-Khalil, in the West Bank. We arrived at a bustling market where the aubergines come in five different sizes and the falafels are fried fresh. Hebron is the “occupation within the occupation.” Across the city center, heavily-fortified checkpoints — tangles of nets, barbed wire, gates and turnstiles — guard illegal Israeli settlements, where the old city center once stood. Above a frightful gate separating a desolate settlement from the city is a machine that some call the “smart shooter” — an automated rifle that can kill an approaching human being if the system deems them a risk. The face of nearly every Palestinian is imprinted in this system, which determines their fate before they can see a human face or hear a human voice. Soldiers can operate the rifle with a joystick — a macabre game of murder that the occupier mediates through a screen and the occupied feels in their flesh.

What is being guarded? A near-empty, lifeless street. A vending machine. A broken-down van. Signs with fabricated history seeking to recast the colonizer’s oppression as victimhood. Flags, lots of flags. Here, in a settlement that is home to some 400 settlers, Palestinians are not allowed to set foot. No trace remains of the bustling life that defiantly continues to exist outside this expanding barricade — life that the settlers grind away with daily volleys of rocks and urine and acid; life that the state actively erases. The Palestinian markets become cages — enclosed on all sides by gates and wire mesh to defend against the settlers’ attacks.

Shuttered shops in Hebron/Al-Khalil. Photo: Pawel Wargan

In Hebron, 1,350 Palestinian shops have been shut by Israeli occupying forces in 23 years, hollowing out the economic life of the city and sowing misery and desperation among its people. 365 children who attend schools near the settlement have to cross three militarized checkpoints twice each day to get to class and return home. In all, there are 28 military checkpoints in an area of under five square kilometers — one for every 25 settlers. As the settlements expand, the beating heart of the city gradually dims.

Right to remain

The geography of the Zionist occupation cannot be measured in straight lines. Jerusalem and Bethlehem are under 10 kilometers apart — a 30-minute drive. But for Palestinians living in Bethlehem, the distance is unassailable. A Palestinian in the West Bank, who still has the keys to his house in Jerusalem, is closer to São Paulo, Johannesburg, or Beijing than to his ancestral home. He cannot travel because the occupation has written the rules that govern his movement. In Jerusalem, residency is granted to those whose “central life” is in the city — an ill-defined legal concept often interpreted at the whims of the occupying authorities. Palestinians forced from their homes in East Jerusalem lose their “central life” in the city. In the process, they lose their right to remain. Losing residency implies total exclusion from social and economic life: you cannot rent a home, open a bank account, enroll at a university, or find work. Roughly 95% of Palestinian construction applications are rejected by Israeli authorities and it is exceedingly difficult for Palestinians to find new housing. And so, they are forced into neighborhoods or camps in the increasingly-populated West Bank, whose land continues to be cut and diced for Zionist settlement.

Since 1950, the Aida Refugee Camp in Bethlehem has been home to thousands of Palestinian families who escaped the Nakba — the campaign of ethnic cleansing that saw Zionist forces evict more than 750,000 Palestinians from their homes in 1948. They came from more than 27 different towns and villages, and more than 6,000 people continue to live there today — in makeshift brick and concrete high-rises that test the limits of structural integrity. The United Nations estimated that the camp’s population density is 77,464 inhabitants per square kilometer — one of the highest in the world. The eight-meter-high separation wall looms over them, casting a permanent shadow on the camp’s perimeter. M. took us up to the roof of a residential building along the wall’s edge. From the top, he inspected the wall and looked at the land it conceals from view: A taunting field of olive trees that stretches across the horizon. “That, in theory, is still within the borders they assigned us, but I’ve never been there,” he said.

In the camp’s claustrophobic alleys, the Zionist regime routinely rehearses its cruel technologies of violence. Every few months, Israeli military trucks spray the neighborhood with excrement, directing their hoses toward open windows. Sometimes, soldiers burst through the walls of homes with explosives, traumatizing children in the process. The stench of tear gas is pervasive; Aida Camp is the area most exposed to tear gas in the world. In the minutes after we arrived, we saw volleys of tear gas canisters erupt from the roof of an armored car — aimed at families who had gathered to pay respects to their deceased relatives at the cemetery. Since Palestinian children had learned to throw teargas canisters out of harm’s way, the United States developed a new grenade — locally dubbed “the butterfly” — that jumps around while it releases the toxic gas. We saw these, too. And, when our delegation visited the cemetery later that evening, the occupation forces threatened us at gunpoint.

The impunity that is allowable before international observers speaks to the horrors that take place in their absence. One night before we arrived at the Aida Camp, Israeli soldiers shot two young men with explosive bullets — munitions that are banned under international law. One lost a leg. The other’s intestines burst out from his abdomen. Both survived even though the Israeli troops left them to die at the side of the road.

The Nakba never ended

When the old colonial powers decry Palestine’s “unprovoked” violence, they whitewash the persistent and creeping violence of the colonial occupation that the Palestinian people have endured in every aspect of their lives for over three-quarters of a century. The Nakba never ended. Since 1948, the people of Palestine have lost over 85% of their land. The militarization of the Israeli state has confined them to a series of open-air prisons, where they are taunted, humiliated, and killed. The Zionists uproot their olive groves. They pour cement into their water wells. They evict their families with tear gas, set their crops alight, or poison their land with chemicals unknown. And that violence has only escalated, with the direct encouragement of Israel’s now openly-fascist government. In the first nine months of 2023, occupation forces killed more Palestinian people in the West Bank than in any year since the United Nations started to keep track.

One of the myths that was shattered by the Palestinian resistance this week is that of Zionism’s invincibility. In fact, this myth was already plainly paper-thin. Despite the routine humiliation and violence, all along the zigs and zags of the occupation we met men, women and children with raised chins, warm smiles, and patient eyes. They welcomed us into their homes and communities, and they told us their stories. The contrast with the occupation forces was inescapable. The further into the West Bank we traveled, the more terrified they appeared. Guns on their triggers, they seemed at all times prepared to unleash disproportionate violence on those around them. It is as if they sensed that the colonial regime could not be sustained at no cost to them — a reality that has now come into sharp focus.

That fragility has its roots in a simple truth: The Palestinian people have no choice. Their lands were invaded. Their families were dispossessed and massacred. Their sovereignty was erased and their riches stolen from under their feet. At every stage, their oppressors had a choice and chose violence. Zionism is bound by a million threads to imperialism and capitalism. In its early days, the Zionist movement received significant backing from the British Empire seeking to maintain its grip in the region after the First World War. Today, it is sustained by the United States and its subordinates as an outpost of empire in West Asia — a forward base designed to advance and cover for the West’s imperialist and ethno-nationalist ambitions in the region. Israel’s fragility, then, is also imperialism’s. The US’s overwhelming show of support for Israel today makes clear that the act of liberation anywhere is a threat to imperialism everywhere.

Zionism is a partner of imperialism

Imperial backing helps sustain a racially-segregationist capitalist economy within colonized Palestine. The early Zionist industrialists came with both machinery and labor. Palestine, in turn, was de-industrialized and its people excluded from employment. As Ghassan Kanafani has written, the very economic foundations of the Zionist state are found in the systematic dispossession and exclusion of the Palestinian people and the creation of a “whites-only” economy for the settlers:

“[Zionist] immigration was not only designed to ensure a concentration of European Jewish capital in Palestine, that was to dominate the process of industrialization, but also to provide this effort with a Jewish proletariat: The policy that raised the slogan of “Jewish labor only” was to have grave consequences, as it led to the rapid emergence of fascist patterns in the society of Jewish settlers.”

Today, the Israeli state is highly dependent on foreign investment. In 2022, its high-tech sector accounted for 48.3% of all exports, a system that is underpinned in part by exploited Palestinian labor — and 80% of venture investments in this sector are based on foreign funds. The Israeli regime is currently implementing a spate of judicial and social “reforms” that have found significant opposition among liberal Israelis, who tolerate the colonial regime insofar as the pretense of liberal democracy, with Jewish primacy, is preserved. As the pretense of liberal democracy withers away, and the colonial face of the Israeli state comes into sharper view, many believe that Israel risks a wave of capital flight that could challenge the very basis of its settler-colonial economy.

Now, “everything is on the table”. This moment has generated a profound and persistent internal crisis in Israeli society, reflected in lost investments at home, critique from partners abroad, and renewed global interest in disinvestment as an anti-apartheid strategy. As representatives of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement told us, “in order to remain supported by capitalism, Israel cannot afford to become extremist Orthodox. Even for capitalism, it must show a face of liberal democracy.” This was one of the factors that burst open the window of opportunity for the Palestinian resistance.

Here, the BDS’s core mission — to sever the arteries of state, institutional, and corporate complicity that power the Zionist project — come into sharp focus. The struggle to liberate Palestine is fundamentally a struggle against capitalism and imperialism. It demands that those living in the imperial countries take the fight to the financiers, corporations and institutions that sustain the occupation. It calls on scientists to refuse to make the gas that poisons Palestinian children, on factory workers to refuse to produce the munitions that crush families in Gaza, and on dockworkers to refuse to load them onto ships. And it calls on us to take seriously the struggle for socialism, because it is only by arresting imperialism’s cancerous spread that the auxiliary violence of Zionism’s colonial domination can be ended once and for all.

The Palestinian people will not give up their struggle for freedom

We cannot abandon the struggle because the Palestinian people have not. At Ramallah University, we saw red flags flying high. An exhibition featuring resistance fighters martyred in Jenin and Nablus saw hundreds of young communists descend on the campus. Young organizers gave us leaflets, announcing their candidacy in the upcoming student elections. They face tremendous headwinds. The attack on Palestinian political organizations is relentless. More than 5,000 Palestinians are held in Israeli jails — and others still are held in jails operated by the Palestinian Authority at Israel’s behest. But organized political power is on the rise. Across Palestine, doctors’ and teachers’ unions organized a historic strike aimed both at the Israeli occupation and the Palestinian Authority’s complicity. Now, as the Palestinian people beat back their occupation, anti-imperialist, socialist, communist, and other popular forces abroad must work to bruise its imperialist backers.

We know that this combined movement will succeed. As Fayez Sayegh wrote in his seminal text, Zionist Colonialism in Palestine, Zionism was anomalous because it “came to bloom precisely when colonialism was beginning to fade away” — a relic of the past that retarded the historical tendency towards liberation. But in the long arc of history, liberation from colonialism is inevitable. As the nations of the world proclaimed in the 1961 UN Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, “the process of liberation is irresistible and irreversible”. The promise of Palestine’s statehood will be realized — from the river to the sea. But until that moment comes, what terrible cost will the Zionist state impose on the Palestinian people for seeking their freedom? And what will we have done to stop it?

No comments:

Post a Comment