Dennis Mersereau

Thu, November 16, 2023

Heartaches are buried in the sands beneath the Great Lakes.

Countless vessels have sailed into the steely embrace of a long November night only to never return. Records of these ill-fated journeys stretch as long as the lakes are deep.

Many of the voyages slipped beneath the dark waters and dragged every soul with them, leaving behind hardly a trace for survivors to find comfort or seek closure.

And the majority of those sunken vessels met their fate in the heart of autumn, felled at the hands of the “witches of November.”

DON’T MISS: The major storm behind Gordon Lightfoot's 'The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald'

Great Lakes host a perfect storm for ill-fated voyages

Superior, Huron, Michigan, Erie, and Ontario all rank among the world’s largest lakes, and combined they hold nearly one-quarter of Earth’s total supply of freshwater.

Sailing through the middle of any of these lakes allows the surrounding land to slip below the horizon, making it feel as if you’re in the middle of the ocean—and, for all anyone knows, you pretty much are. The centre of each lake is dozens of kilometres from the nearest shore, essentially stranding anyone who needs help until help can slowly come to them.

These lakes are the picture of serenity during the warm months, and they’re quiet fields of ice in the heart of winter. But during the peak of autumn, as winter’s chill violently sweeps away summer’s heat, the Great Lakes are ground zero for some of the continent’s roughest conditions.

MUST SEE: Nuclear snow? Seven strange ways humans can change fall weather

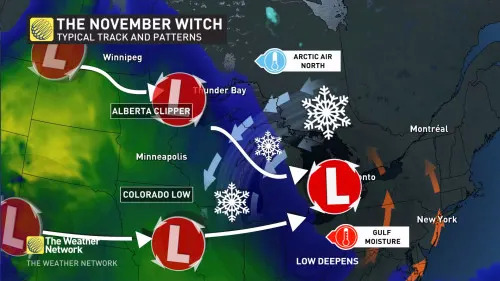

Powerful fall storms trekking across the U.S. and Canada often find their way over the Great Lakes. These low-pressure systems are fuelled by a jet stream that thrives on the changing seasons. Frigid air from the Arctic rushes south behind the storm, colliding with stout winds blowing in warm air from the south.

For as rough as conditions are on land when these storms take hold, the atmospheric blender roaring over the open water is magnitudes worse.

Gale-force winds frequently blow during these rollicking fall storms as air rushes over the Great Lakes without the friction of trees or soil to slow them down. Wind gusts of 100+ km/h are common over the open waters, whipping up waves that can tower above the deck of a cargo ship.

WATCH: The SS Edmund Fitzgerald was the largest freighter to sink in the Great Lakes

Centuries of shipwrecks lie beneath the Great Lakes

Relentless winds, billowing waves, and near-zero visibility are a recipe for disaster when a ship is lurching about and hours away from safe harbour.

Mariners have long called these ferocious storms the witches of November. Plenty of theories swirl around the etymology of the phrase itself. It could be a leftover from the recently departed Halloween season, or a reference to the “witch’s brew” of rough weather these awful storms bring.

READ MORE: The science behind Canada's 'classic' fall storms

The phrase could also find its roots in superstitious sailors who feared setting out into the November horizon.

It’s a fear with merit.

Legendary Canadian musician Gordon Lightfoot immortalized one particular witch of November in The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald. His ballad recounts the loss of the SS Edmund Fitzgerald and its crew in a terrible storm on Lake Superior on November 10, 1975.

A surface analysis of the Armistice Day Blizzard on November 11, 1940. (NOAA)

While it’s the region’s most well-known shipwreck, it was one in a long list of vessels lost beneath the waves.

A fierce storm that swept the Great Lakes in November 1905 claimed nearly 30 vessels throughout the region, including the SS Mataafa, killing dozens of sailors. Another powerful November gale hit in 1913, reportedly killing hundreds of mariners.

RELATED: How Colorado lows and Texas lows affect our weather in Canada

Before the storm that claimed the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, the Armistice Day Blizzard of 1940 served as a prime example—and historical warning—of the witches of November. This classic Colorado low erupted over the central United States, hitting the Great Lakes on November 11 with record-low air pressure readings across the U.S. Upper Midwest.

The historic blizzard in 1940 swept the Lakes with 100+ km/h winds and whiteout conditions, leading to snow drifts towering more than 6 metres high in spots. The storm reportedly claimed dozens of mariners after the wind and waves proved too much for their vessels to stand.

Hundreds of sunken ships lie at the bottom of those treasured lakes. The peaceful sands of their frigid depths give rest to crews who tried to battle the witches of November until their last moments.

WATCH: Film crew discover 128-year-old shipwreck in Lake Huron during shoot

Header image: Dale Matthies/Submitted Header image courtesy of NOAA.

No comments:

Post a Comment