Christ Church at 50: How Doug Wilson pushed Christian nationalism to the center

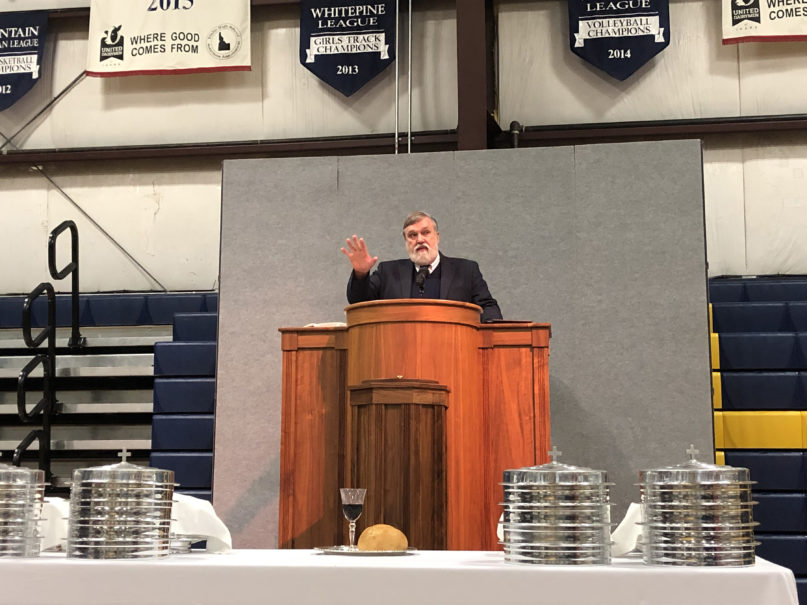

Pastor Doug Wilson leads a service as Christ Church meets in the Logos School gymnasium on Oct. 13, 2019, in Moscow, Idaho. (Photo by Tracy Simmons, File)

Tracy SimmonsDecember 10, 2025RNS

MOSCOW, Idaho (RNS) — In 1977, Doug Wilson stepped behind the pulpit of a small Pullman, Washington, church for the first time. The 24-year-old Navy veteran, now armed with a guitar, had been leading worship at the 2-year-old congregation when the church’s lead preacher left unexpectedly. Wilson had no grand vision of building a movement, or that Christ Church, as it came to be called, would one day be the most scrutinized congregation in America.

“There’s no real objective explanation for it,” Wilson, now 72, said of his church’s moment in the national spotlight in a recent interview. “I think it’s the hand of God.”

But critics say that Christ Church’s renown has less to do with the Almighty than with Wilson’s dedication to Christian nationalism and his ties to like-minded officials in the Trump administration and among its allies. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth has attended a Christ Church-affiliated congregation in Tennessee and has amplified Wilson’s most controversial views, including his argument that women should not be allowed to vote. In the space of a month in April 2024, Wilson was interviewed by Tucker Carlson and Charlie Kirk on their respective podcasts.

Christ Church has also had a powerful effect on its own community, drawing approximately 3,000 of Moscow’s population of 25,000, as well as on the conservative Christian world, through a network of affiliated churches, schools and media platforms spanning the globe.

“What’s happening here is we’re punching way above our weight class,” Wilson said. “And so if you looked at everything on paper, none of this should be happening.”

When Wilson began pastoring in 1977, he embraced the theological framework of his Jesus People roots — conservative evangelical Baptist theology with an emphasis on personal conversion and contemporary worship. That changed in 1988, when he encountered what he considered a dangerous theological drift in the congregation.

Doug Wilson in his office in Moscow, Idaho. (Photo by Tracy Simmons)

“Someone in the community started teaching what’s called openness of God theology,” Wilson recalled, referring to a view that God doesn’t fully know the future. “That appalled me.”

His search for a theological response led him to Reformed theology and John Calvin’s teachings on God’s sovereignty. “I started reading … went down the wormhole and became a Calvinist in ’88,” Wilson said. The congregation followed his shift.

By 1993, Wilson had also embraced paedobaptism — baptizing infants — and Presbyterian church governance. In 1998, he formalized relationships with two sister congregations in Washington state to create what became the Communion of Reformed Evangelical Churches, which has grown to approximately 170 congregations as far away as Eastern Europe, the Philippines and Japan.

Wilson extended his influence through the Logos School, founded in 1981, launching what became the nationwide classical Christian education movement. The Association of Classical Christian Schools, which emerged from that effort, now represents hundreds of schools across the country. In the 1990s, Wilson established Canon Press, a publishing house; New St. Andrews College, a Reformed Christian liberal arts institution; and Greyfriars Hall, a ministerial training program.

Wilson came to national attention in 2003, when he organized a conference at the University of Idaho at Moscow about revolutions throughout U.S. history. Some in the community picked up on a booklet titled “Southern Slavery, As It Was” that Wilson had co-authored some years earlier arguing that slavery, besides being allowed for in the Bible, was not as harsh in the antebellum South as is commonly portrayed. Soon the campus and downtown Moscow were plastered with flyers referring to Wilson’s university event as a “slavery conference.”

The national media picked up the story, sparking protests, but Wilson showed an unwillingness to back down from controversy, and in the decades since he has established a pattern of provocative statements on race, gender and sexuality.

People are arrested during a “psalm sing” event promoted by Christ Church

during the COVID-19 pandemic in October 2020, in Moscow, Idaho. (Video screen grab)

He made national news again during the COVID-19 pandemic, when he and other church members gathered maskless at Moscow City Hall in what Wilson termed “civil disobedience” against public health orders. His blog readership expanded dramatically, and his views on politics, culture and theology became more widely known.

“It was COVID that sort of kicked us into the mainstream across topics,” Wilson said.

Christ Church’s profile in the national debate is at odds with its relationship with its neighbors. The church has steadily acquired properties along Moscow’s Main Street, drawing protests from residents. Church members, meanwhile, own restaurants, coffee shops, a brewery and other establishments.

In May, library board candidates who espoused Christ Church values lost decisively. In November, three candidates backed by Liberty PAC — a political action committee funded primarily by Christ Church elder Andrew Crapuchettes’ company, 3100 Capital LLC — were defeated in races for mayor and City Council.

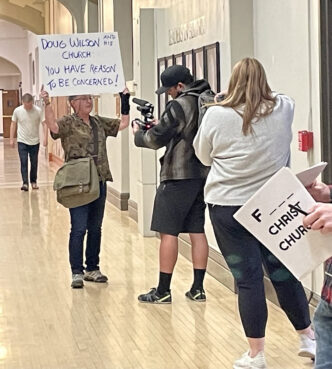

Keely Emerine-Mix, left, protests before a town hall meeting with Christ Church on April 11, 2024, in Moscow, Idaho. (Photo by Tracy Simmons/FāVS News, File)

One council candidate, John Slagboom, who attends All Souls Christian Church, took offense at suggestions he was tied to Christ Church. “What Liberty PAC did was totally out of my control,” Slagboom said.

Wilson said, “Basically, anybody who’s even mildly conservative and a Christian is going to be tagged as a kirker, whether they are or not,” using the local term for a member of the church.

Moscow’s resistance may reflect an inherent weakness in Wilson’s strategy, said Kate Bitz, a senior organizer at the Western States Center, a civil rights organization that tracks organized bigotry in the Pacific and Inland Northwest. Wilson’s Christian nationalism, said Bitz, “is an inherently anti-democracy movement that does not care for religious freedom, and that, in fact, would like every church in town to bend to their exact interpretation of the Bible.”

The Western States Center has tracked organized bigotry in the region since the 1980s — from Aryan Nations compounds to paramilitary movements to today’s Christian nationalist organizing. Wilson fits within that continuum, Bitz said, pointing to his history of defending aspects of chattel slavery and his statements about LGBTQ+ people and gender roles.

Wilson’s rhetoric about “bringing faith into the public square” or “defending religious freedom” may obscure authoritarian aims, she said, but once voters understand that ultimate goal, the message loses appeal, even in conservative areas.

But Wilson explains his strategy through a concept he’s promoted for years: “assuming the center” — “acting with authority before you actually have any,” he explained. It’s a move that capitalizes on what Wilson sees as a vacuum created by faltering mainstream institutions.

Pastor Doug Wilson addresses the National Conservatism Conference,

Sept. 4, 2025, in Washington. (RNS photo/Jack Jenkins)

Never has the strategy seemed to pay off more than now. “If Kamala (Harris) had been elected, there would have been virtually no evangelical Christians in the administration,” Wilson said. “With (Donald) Trump in the White House, the administration is crawling with them.”

To maximize his footprint in Washington, Wilson planted a church there this year, introducing what Wilson critic Kevin DeYoung called “the Moscow mood” — cultural engagement “with a spirit of … having fun while you’re doing it.”

Wilson maintains that he is focused more on changing the culture of the capital, rather than partisan campaigning. “We have a political agenda, but not a partisan, right-this-minute agenda,” he said. “We believe the church is inescapably political, but we also believe it ought not to be partisan in a ‘vote for Murphy’ kind of way.”

Rabbi Daniel Fink, retired from Boise’s Congregation Ahavath Beth Israel, said Wilson’s national influence represents a troubling trend. “For many years, I hoped that Idaho would moderate to grow more like the rest of America,” Fink wrote in a recent column in the Idaho Statesman. “Instead, America is becoming more like Idaho.”

Pastor Douglas Wilson speaks before Communion during a

Christ Church service in the Logos School gymnasium on Oct. 13, 2019

, in Moscow, Idaho. (Photo by Tracy Simmons, File)

Fink, who has lived in Idaho for 32 years, sees Wilson as a leading figure in a movement to “replace democratic governance with fundamentalist rule.” He pointed to Idaho’s abortion ban, attacks on LGBTQ+ rights and efforts to funnel taxpayer dollars to religious institutions.

“I’ve seen what this agenda has done to Idaho,” Fink said in an interview with RNS. “It should serve as a warning for all Americans.”

After nearly 50 years, Wilson shows no signs of slowing down. He preaches regularly, writes prolifically on his “Blog & Mablog” and travels to speak at affiliated churches. But with a tentative plan calling for Wilson to step aside as senior minister at 75, transition plans have begun to take shape. His son, N.D. Wilson, who is an elder in the church, won’t take over. “He’s more of a prophet than I am,” Wilson said. “His gifts would be — he needs to be doing what he’s doing.”

Instead, the next senior minister will likely come from within the community’s “deep bench” of capable leaders, Wilson said. He expects to share preaching duties for a time and rotate through different church plants in the area. ”I want to preach until I die, or as long as I’m able,” he said.

No comments:

Post a Comment