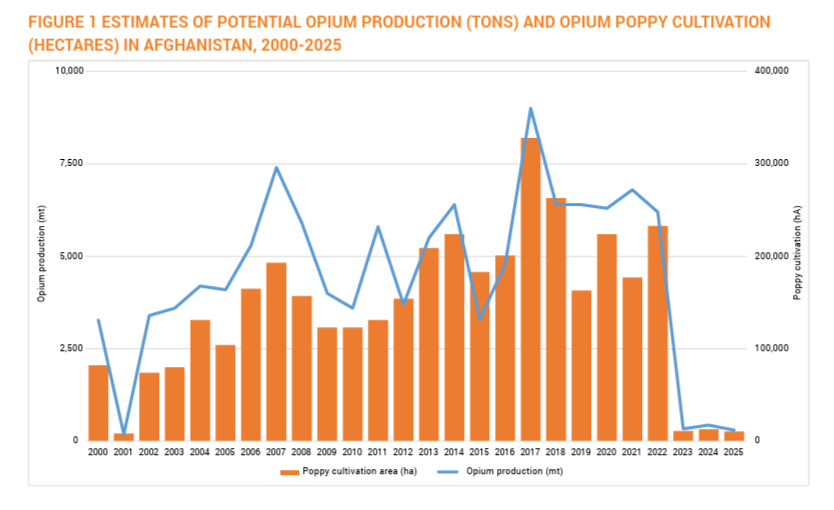

Opium production in Afghanistan boomed during the two decades in which largely US forces propped up a Washington-approved government – but it has collapsed since the Taliban retook power in the country in August 2021.

The stark decline in both poppy cultivation and opium output is explored in the Aghanistan Opium Survey 2025, released by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

It shows that sustained enforcement of a ban on growing opium poppy crops, combined with drought conditions that caused crop failures, have driven down output, especially in Badakhshan, a northeastern province of Afghanistan bordering Tajikistan, China and Pakistan that is the country’s main opium poppy producing province.

The survey says that last year in Afghanistan there was an estimated potential production of 296 tonnes of opium that could be converted into approximately 22-34 tonnes of export-quality heroin. That compares to an estimated 32-50 tonnes in 2023 and an estimated 350-580 tonnes in 2022.

Credit: Afghanistan Opium Survey, UNDOC.

The report notes that in “the 2025 season, most farmers continued to adhere to the ban on opium poppy cultivation, which is in its third year of enforcement.

“The total area under opium poppy cultivation in 2025 was estimated at 10,200 hectares, 20% lower than in 2024 (12,800 hectares) and a fraction of the pre-ban levels recorded in 2022, when an estimated 232,000 hectares were cultivated nationwide.”

The UNODC – which refers to the Taliban administration as the De facto Authorities, or DfA, of Afghanistan, given their lack of international recognition beyond that lately granted by Russia – said that the DfA reported that over 4,000 hectares of opium poppy were eradicated in the country in 2025, “although UNODC could not technically verify this number”.

While lower than the 16,000 hectares reported by the Taliban – ideologically opposed to all illicit narcotics – as eradicated in 2024, “this still corresponds to about 40% of the estimated cultivation area”, the UNODC report says.

It adds: “Eradication efforts occasionally sparked violent resistance, particularly in the northeast, where protests led to unrest and casualties.”

The report also assesses that given falling production and falling prices, Afghan farmers’ income from opium sales to traders dropped by 48% from $260mn in 2024 to $134mn in 2025. This decline resulted from falling production and falling prices.

A truck carrying thousands of pounds of processed wheat rolls goes by in Helmland province. Persuading farmers to swtich to legal crops is tough when the profits available from poppy cultivation are so much higher (Credit: Cpl. Marco Mancha, USMC, cc, ID 110719-M-PE262-373).

Afghan farmers’ income from opium sales remained at historic lows last year, observes the report, stating: “In 2025, opium prices declined from the previous year but remained well above pre-ban levels. Although opium is traded at elevated prices, relative to the pre-ban period, the amounts produced in the most recent year have been some of the lowest in decades.

“In 2024, the average seasonal price for a kilogram of dry opium was US$780 at the trader level; in 2025, the average seasonal price was at US$570, a year-on-year decline of about 26%, but still more than five times higher than the long-running pre-ban average below US$100 a kilogram.”

Credit: Afghanistan Opium Survey, UNDOC.

“In 2025, declining opium prices and smaller yields meant that a hectare of opium generated about US$17,000 in Helmand (a 43% decline from the previous year) and around US$12,000 in Badakhshan (35% less than in 2024).

“Despite this drop, opium remained far more profitable than most licit crops. For comparison, staple crops such as wheat yielded only about US$800 per hectare, while a key cash crop like cotton provided roughly US$1,600 per hectare to farmers.”

The sustained high opium crop prices might have triggered opium poppy cultivation in countries in the immediate region around Afghanistan, the report warns.

“For instance, [providing an indication of this] eradication of opium poppy in two countries near Afghanistan increased from 5,868 hectares in 2022 to 13,200 in 2023 (latest official data available),” says the report.

It adds: “Market indicators suggest supply from elsewhere, too, as opiates seizures and opium prices fell despite reduced opium production from Afghanistan and the fairly steady nature of demand for opiates.

“Such a shift could be an example of the so-called balloon effect, where enforcement in one country leads to the displacement of illegal activities to another – a phenomenon that has been observed elsewhere.”

Looking at another consequence of the ban on opium poppies in Afghanistan, the report says: “Trafficking in synthetic drugs, especially methamphetamine, seems to have increased since the ban, with seizure events in and around Afghanistan higher than before, indicating a growing risk of synthetic drug substitution as opiate production falls.

“Prices for methamphetamine in Afghanistan and neighbouring countries have also decreased in line with higher seizure volumes. UNODC’s systematic monitoring of methamphetamine prices in Afghanistan began in late 2022, and monthly kilogram prices initially fluctuated between US$600 and US$850.

“Beginning in late 2024, methamphetamine prices fell sharply, dropping below US$600 per kilogram. The price decline together with increasing seizures can reflect an increase in production capacity or greater availability stemming from inflows from other countries; at present, neither dynamic has been conclusively verified, and both remain plausible contributors to the observed shift.”

No comments:

Post a Comment