From the Battle of Okinawa to the New Cold War

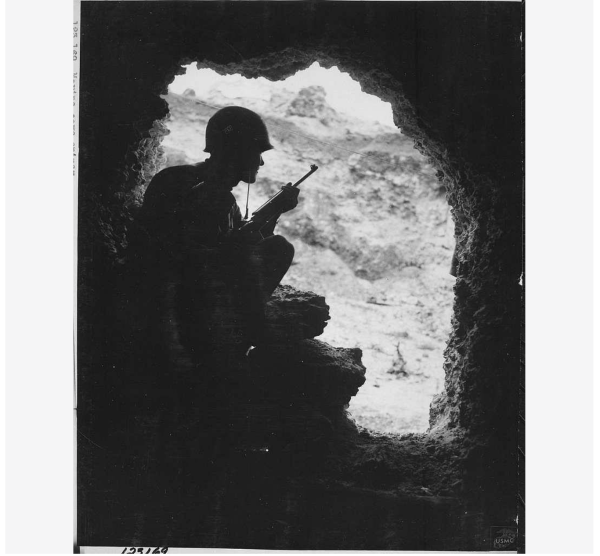

We descended into Chibichibi Cave in southern Okinawa with the heavy feeling that this was not a site of distant history, but a warning. The cave is low enough that you have to bend forward as you walk. The air is damp, the light disappears quickly, and the air becomes suffocatingly warm. In April 1945, as US forces landed on the island, 140 Okinawan civilians—mostly elders, women, and children—hid here. Eighty-five of them would die by their own hands. Parents killed their children first, then themselves.

This was not an act of collective madness, nor a cultural predisposition to suicide. What happened here was manufactured. It was the consequence of disinformation used as a weapon of war.

At Chibichibi, Okinawan civilians had been told by the Japanese Imperial Army that US soldiers were “red devils” who would rape and torture them. They were taught that capture was shameful, that as subjects of the emperor they must never surrender. Terrified, trapped, and cut off from reliable information, families acted on lies that proved fatal. In a neighbouring cave, everyone survived—because two people had lived in Hawaii, and some had first-hand knowledge of the United States that contradicted Japanese education, and had the means to communicate with US soldiers.

Takamatsu Gushiken, known locally as the “bone digger,” guided us through the cave. He is also one of the core members of the local activist group, No More Battle of Okinawa. For decades, he has helped recover the remains of hundreds of people killed during the Battle of Okinawa. Before entering, he asked a simple question: Why are we going into this cave? His answer was equally simple—because we do not want this to happen again. Not in Okinawa, not in Asia, not anywhere.

Okinawa makes up just 0.6 percent of Japan’s landmass, yet it hosts roughly 70 percent of all US military facilities in Japan, one of the most militarised colonies of the US. Seeing it firsthand, one quickly realises that this is not a matter of isolated bases; it is an overwhelming military encirclement. Fences cut off coastlines, fighter jets thunder overhead, and entire communities are hemmed in by infrastructure built for war. Calling these installations “bases” is misleading—they function more like a permanent occupation embedded into everyday life.

Today, in the heightened New Cold War that the US is imposing on China, this infrastructure is expanding. The same island that was sacrificed as a battlefield in 1945 is being prepared for sacrifice again.

At Henoko, a once-pristine coastal area known locally as a “hope spot,” a new military base is being constructed on reclaimed land, despite repeated local opposition documented by the Okinawa Prefectural Government and international observers. For nearly three decades, Okinawans have resisted this project through elections, referenda, court cases, and daily acts of civil disobedience. All have been ignored. Since 2014, elderly protesters—many in their seventies and eighties—have gathered every single day at the gates of Camp Schwab, sustaining a daily resistance for more than a decade. They sit on folding chairs, block trucks carrying landfill material, and are forcibly removed by security guards and police. As they are dragged away—by their own community members, men the age of the protesters’ sons, grandsons, students, and neighbours—they sing: “No to war.” “Protect nature.” “Don’t give away our children’s future.”

Hundreds of trucks pass through daily, carrying sand and stone to fill the sea. Some of that soil comes from areas where the remains of those killed in the Battle of Okinawa are still being recovered. “This is like killing the dead a second time,” Gushiken tells us.

To understand why Okinawa bears this burden, we have to look beyond the present moment. The Ryukyu Kingdom, which once governed these islands, maintained diplomatic and trade relations across East and Southeast Asia for centuries. It was forcibly annexed by Japan in 1879 and subjected to systematic cultural suppression. Okinawan languages were banned in schools, economic development was deliberately stunted, and discrimination was institutionalised. During the Battle of Okinawa in 1945, approximately one quarter of the civilian population was killed, a figure established in postwar historical research and official Okinawan memorial records. Japanese troops used civilians as human shields and coerced mass suicides, particularly in Okinawa—a pattern not seen on the Japanese mainland.

After Japan’s defeat, Okinawa remained under direct US military rule until 1972. Even after its “reversion” to Japan, the bases stayed. Land seizures, environmental contamination, and crimes committed by US personnel—often shielded from local justice—became enduring features of life on the island.

Today, Okinawa is being transformed once again, this time into a frontline staging ground in an increasingly militarised regional order, as outlined in US strategic planning documents and war-game assessments that explicitly depend on bases in Okinawa. New missile deployments, base expansions, and joint military exercises are carried out in the name of “security,” while local democratic opposition is overridden as an inconvenience. Every available channel—elections, referenda, lawsuits—has been exhausted. When Okinawan votes conflict with military priorities, they are simply ignored.

Yet the resistance of Okinawan has been continuous and deeply rooted. Women’s organisations have documented decades of sexual violence linked to the military presence, most notably Okinawa Women Act Against Military Violence, which has maintained detailed case records since the mid-1990s. Teachers’ unions, farmers, artists, and religious groups have all played roles in the anti-base movement. Sculptor Kinjo Minoru spent ten years creating works that trace life before, during, and after the war, insisting that memory itself is a form of resistance. Artists, musicians, and educators continue to insist that peace education is not optional—it is a matter of survival.

One guide told us that for thirty years after the war, families from the same village did not speak to each other about what happened in the caves. The trauma was too deep. Only later did people begin to ask the hardest question of all: Why did this happen here? The answer leads back, again and again, to colonial domination, militarised education, and information controlled by those preparing for war.

Chibichiri Cave is a warning from the past, reminding us that those who died there were not irrational, but were tragic victims of fear-mongering. Rather than being incidental to the war, disinformation was part of its logistics. In an era of escalating hyperimperialist military aggression of the United States—from Okinawa to Gaza, from Iran to Venezuela—disinformation once again plays a central role in shaping public consent for war.

Okinawa reminds us that war does not begin with bombs. It begins with stories—about enemies, about threats, about inevitability. And it reminds us that resisting war requires more than slogans, and contesting the disinformation campaigns in the New Cold War requires solidarity based on communication, exchange of reliable information, and a refusal to accept narratives of dehumanisation.

As we left the cave, Gushiken’s question came up again: Why do we go inside? We go because to remember is to take on responsibility. Okinawa is small, as a local saying goes, but you cannot swallow a needle. Despite decades of occupation and sacrifice imposed by others, Okinawans continue to resist being used as a battlefield, from World War II to the New Cold War. Remembering Okinawa is not about the past; it is about refusing to be prepared for war in the present.

As Gushiken put it plainly before we left the cave: “The problems we see today in Okinawa with the US and Japan are the result of the unresolved problems of 1945, and the Battle of Okinawa.” This insistence—that the war never truly ended here—is the political and moral core of the demand and the movement he is part of: No More Battle of Okinawa.

Tings Chak and Atul Chandra are the Asia co-coordinators of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

No comments:

Post a Comment