Governing Crisis—Sanctions, Austerity and Social Unrest in Iran

On December 28, 2025, protests erupted across multiple cities in Iran in response to currency collapse and spiraling living costs. As the exchange rate grew more volatile, sections of Tehran’s Grand Bazaar and commercial centers shuttered. Rapidly shifting prices made imports, pricing and trade impossible.

The state moved quickly to implement an emergency measure embedded in its 2025–2026 fiscal-year budget package: It removed preferential foreign exchange rates for essential goods and key production inputs. Officials presented the move as anti-corruption reform and promised direct compensation through cash transfers and targeted support. In practice, the change accelerated an already rapid rise in prices and further eroded purchasing power, shifting the burden onto households. Official inflation in December was reported to be around 42 percent, but the cost of basic groceries rose much faster at 72 percent compared to a year earlier, pushing staples such as bread and dairy out of reach for large segments of the working class. By early January, the removal of preferential foreign exchange rates had only deepened the squeeze on everyday consumption, and protests escalated into mass demonstrations across the country that lasted for weeks.

It was not the first time Iranian officials have provoked unrest by introducing regressive measures in the name of reform. Over the past decade, successive governments have framed price liberalization and currency adjustments as necessary steps to stabilize markets and curb insider profiteering and corruption. In practice, these policies have functioned as austerity measures, transforming service-based welfare programs into cash-based handouts that quickly lose value amid chronic inflation.

The 2010, and later 2019, fuel price hikes are notable earlier examples of this shock politics, with the latter fomenting a mass uprising against deteriorating economic conditions. Both protests were put down with lethal repression. The current moment has followed the same arc at a higher intensity. This time, the masked austerity measures were implemented amid an economic protest. By mid-January the government was estimated to have killed thousands and had placed the country under an indefinite communication blackout (internet and phone) in one of the deadliest episodes in the Islamic Republic’s history since the purges of political dissent in the 1980s.

On December 28, 2025, protests erupted across multiple cities in Iran in response to currency collapse and spiraling living costs. As the exchange rate grew more volatile, sections of Tehran’s Grand Bazaar and commercial centers shuttered. Rapidly shifting prices made imports, pricing and trade impossible.

The state moved quickly to implement an emergency measure embedded in its 2025–2026 fiscal-year budget package: It removed preferential foreign exchange rates for essential goods and key production inputs. Officials presented the move as anti-corruption reform and promised direct compensation through cash transfers and targeted support. In practice, the change accelerated an already rapid rise in prices and further eroded purchasing power, shifting the burden onto households. Official inflation in December was reported to be around 42 percent, but the cost of basic groceries rose much faster at 72 percent compared to a year earlier, pushing staples such as bread and dairy out of reach for large segments of the working class. By early January, the removal of preferential foreign exchange rates had only deepened the squeeze on everyday consumption, and protests escalated into mass demonstrations across the country that lasted for weeks.

It was not the first time Iranian officials have provoked unrest by introducing regressive measures in the name of reform. Over the past decade, successive governments have framed price liberalization and currency adjustments as necessary steps to stabilize markets and curb insider profiteering and corruption. In practice, these policies have functioned as austerity measures, transforming service-based welfare programs into cash-based handouts that quickly lose value amid chronic inflation.

The 2010, and later 2019, fuel price hikes are notable earlier examples of this shock politics, with the latter fomenting a mass uprising against deteriorating economic conditions. Both protests were put down with lethal repression. The current moment has followed the same arc at a higher intensity. This time, the masked austerity measures were implemented amid an economic protest. By mid-January the government was estimated to have killed thousands and had placed the country under an indefinite communication blackout (internet and phone) in one of the deadliest episodes in the Islamic Republic’s history since the purges of political dissent in the 1980s.

The Political Economy of Sanctions

Most commentary on political crisis in Iran oscillates between two convenient, reductive narratives. The problem is either corruption and mismanagement, as if Iran’s economy operates in a vacuum untouched by global capitalism, or, echoing the state’s own narrative, sanctions and imperialist hostility are treated as the singular root of the country’s problems. Both stories flatten a complicated reality. The more useful question is how sanctions have been absorbed into Iran’s political economy in ways that serve the interests of the ruling class. Sanctions have not suspended market-oriented restructuring in Iran. They have reshaped it by widening the state’s discretionary power over who gets access to dollars, permits and contracts, and by generating new opportunities for insider profiteering under the guise of reform. Any serious account of Iran’s crisis must confront both the external sanctions regime and the internal machinery that manages crisis through austerity and repression.

Any serious account of Iran’s crisis must confront both the external sanctions regime and the internal machinery that manages crisis through austerity and repression.

Sanctions have shaped Iran’s political economy since 1979, with sharp escalations in 2012 targeting oil and finance, in 2018 after the US withdrawal from the nuclear agreement (when sanctions were reimposed) and again in late 2025 with the reinstatement of UN and EU-level “snapback” sanctions. Over the past 15 years, these punitive measures have translated into chronic inflation, collapsing real wages and a deepening crisis of social reproduction. Since late 2017, livelihood struggles have repeatedly spilled into open contention, from the 2017–2018 uprising to the 2019 fuel protests to recurring, decentralized mobilizations across workplaces and communities. A decade-long wave of organized labor protest has also persisted with teachers, pensioners and contract oil and petrochemical workers mobilizing over contracts, wages, pensions and basic living costs.

Sanctions did not contribute to the crisis simply by reducing resources. They have also reshaped who gains and how. By creating hard-currency shortages and blocking routine cross-border payments, they pushed trade into opaque channels, weakened the currency and made basic pricing increasingly unstable. One outcome is what many inside Iran call the “trustee economy,” referring to the expansion of intermediaries that keep exports moving, especially oil, by routing payments around banking and SWIFT restrictions. These brokers—often linked to state or quasi-state networks—profit through fees, exchange-rate markups and control over when payments are released, including by delaying or withholding export revenues that are supposed to be brought back into the country. Since 2018, official statements have repeatedly claimed that a significant share of export foreign currency has not been repatriated, with some estimates as high as 30 percent, amounting to tens of billions of dollars.

A related but distinct mechanism operates within the domestic economy. The state has attempted to manage volatility through multiple exchange rates, preferential foreign exchange and discretionary import permissions, turning political access into profit. When hard currency is scarce, the state’s allocation regime channels subsidized dollars and import license through institutional gatekeeping that predictively favors politically connected firms, creating lucrative opportunities for those positioned closest to these bottlenecks.

The Debsh Tea company scandal offers one glaring example. Between 2019 and 2022, Debsh Tea, a privately owned importer and producer, received billions of dollars in preferential foreign exchange earmarked for essential imports. In late 2023, Iranian oversight bodies and judiciary-linked reporting alleged that a significant portion of this subsidized currency was not used for the declared imports and was instead diverted into open-market transactions—turning access to cheap dollars into a quick profit by capturing the gap between the preferential and market exchange rates. The sums reported—upwards of $3 billion—was large enough to cover years of national tea demand or finance major public investment.

Not every case becomes a national headline, but the mechanism is familiar. Similar audit controversies have surfaced before, involving preferential access to foreign currency that did not match verified import records or any documented return of the money. One widely cited instance is the Supreme Audit Court dispute over $4.8 billion in preferential foreign exchange reportedly disbursed to importers with no corresponding imports documented.

When the resulting legitimacy crisis becomes intolerable, the state rolls out corrective packages presented as anti-corruption reforms. In practice, these policies entrench austerity and deliver sudden price shocks. Health policy offers a clear example. The Daroyar reform—a 2022 overhaul of drug subsidies—ended preferential foreign exchange for medicine and shifted the subsidy to an insurance-based reimbursement system. In theory, patients would pay less at the pharmacy while insurers and the state covered the difference. In practice, the financing chain never stabilized: Delayed reimbursements and liquidity shortages increased out-of-pocket costs and produced persistent gaps in access for patients and pharmacies alike. Meanwhile, the government captured fiscal gains from changes in the exchange rate, banks benefited as suppliers and importers relied more heavily on high-cost borrowing. Fuel policy has followed a similar pattern. Price hikes were justified as a way to fund targeted redistribution through cash transfers, but transfers quickly lagged behind high inflation, leaving households to absorb the widening gap between what they received and the real cost of fuel.

The broader state response to the sanctions driven fiscal crisis follows a familiar path. Rather than meeting its obligations through stable public funding, it has leaned on privatization, debt-for-asset swaps and “productive use” (Movaledsazi) schemes that transfer public assets into private hands. A notable example is the pension system. Instead of paying down its debt to Social Security in cash, the government has increasingly transferred shares in state-owned firms, effectively forcing the pension system to finance benefits through dividends, asset sales and investment returns. This policy shifts risk onto retirees by tying their livelihoods to market performance and inflation rather than stable entitlements.

The result is a sanctioned political economy in which austerity becomes a governing tool, and scarcity generates profit for those with privileged access. Instead of protecting households through social provision, so-called anti-corruption reforms shift the costs and risks downward through devaluation and subsidy removal while preserving the allocation systems that advantage well-connected elites. This pattern is widely noted in sanctions-era analyses of inequality and distribution. Recent official estimates put poverty at roughly a third of the population; similarly, the World Bank estimates that close to 10 million people fell into poverty over the past decade.

The result is a sanctioned political economy in which austerity becomes a governing tool, and scarcity generates profit for those with privileged access.

The downward redistribution is visible in how quickly economic shocks travel outward from the commercial core to outlying towns and provinces and in the forms of anger they produce. In western Iran’s long marginalized regions, in towns like Abdanan, the crisis has hit earlier and harder than in many central provinces, leaving deep underinvestment, high unemployment and entrenched poverty. During the recent protest wave, demonstrators stormed a supermarket and tore open bags of rice, scattering the grain across the floor and into the street rather than carrying it away. By late December, a 10kg bag of rice was selling for around several million toman, roughly equivalent to a month of minimum wage income. The gesture was not theft so much as refusal and a public rejection of a system that turns a basic staple into a luxury while demanding that people accept humiliation as everyday submission.

When crisis is managed through shock transfer rather than redistribution, policy becomes part of the problem, producing a vicious cycle. As economic instability intensifies, the state responds with new rounds of austerity framed as reform. Households do not experience these measures as repair; they experience them as a cost shift that deepens the crisis of everyday survival. The usual channels for complaint and mediation lose credibility. People can petition officials and institutions, but those same institutions are either implementing the damaging reforms or lack the power to reverse them. As that legitimacy erodes, pressure accumulates until a trigger can diffuse economic hardship into a national protest moment. Once dissent spills outside institutional channels, the state increasingly treats it as disorder. With fewer credible mechanisms of incorporation left, repression becomes routine because it is the only tool remaining to retain control.

Most commentary on political crisis in Iran oscillates between two convenient, reductive narratives. The problem is either corruption and mismanagement, as if Iran’s economy operates in a vacuum untouched by global capitalism, or, echoing the state’s own narrative, sanctions and imperialist hostility are treated as the singular root of the country’s problems. Both stories flatten a complicated reality. The more useful question is how sanctions have been absorbed into Iran’s political economy in ways that serve the interests of the ruling class. Sanctions have not suspended market-oriented restructuring in Iran. They have reshaped it by widening the state’s discretionary power over who gets access to dollars, permits and contracts, and by generating new opportunities for insider profiteering under the guise of reform. Any serious account of Iran’s crisis must confront both the external sanctions regime and the internal machinery that manages crisis through austerity and repression.

Any serious account of Iran’s crisis must confront both the external sanctions regime and the internal machinery that manages crisis through austerity and repression.

Sanctions have shaped Iran’s political economy since 1979, with sharp escalations in 2012 targeting oil and finance, in 2018 after the US withdrawal from the nuclear agreement (when sanctions were reimposed) and again in late 2025 with the reinstatement of UN and EU-level “snapback” sanctions. Over the past 15 years, these punitive measures have translated into chronic inflation, collapsing real wages and a deepening crisis of social reproduction. Since late 2017, livelihood struggles have repeatedly spilled into open contention, from the 2017–2018 uprising to the 2019 fuel protests to recurring, decentralized mobilizations across workplaces and communities. A decade-long wave of organized labor protest has also persisted with teachers, pensioners and contract oil and petrochemical workers mobilizing over contracts, wages, pensions and basic living costs.

Sanctions did not contribute to the crisis simply by reducing resources. They have also reshaped who gains and how. By creating hard-currency shortages and blocking routine cross-border payments, they pushed trade into opaque channels, weakened the currency and made basic pricing increasingly unstable. One outcome is what many inside Iran call the “trustee economy,” referring to the expansion of intermediaries that keep exports moving, especially oil, by routing payments around banking and SWIFT restrictions. These brokers—often linked to state or quasi-state networks—profit through fees, exchange-rate markups and control over when payments are released, including by delaying or withholding export revenues that are supposed to be brought back into the country. Since 2018, official statements have repeatedly claimed that a significant share of export foreign currency has not been repatriated, with some estimates as high as 30 percent, amounting to tens of billions of dollars.

A related but distinct mechanism operates within the domestic economy. The state has attempted to manage volatility through multiple exchange rates, preferential foreign exchange and discretionary import permissions, turning political access into profit. When hard currency is scarce, the state’s allocation regime channels subsidized dollars and import license through institutional gatekeeping that predictively favors politically connected firms, creating lucrative opportunities for those positioned closest to these bottlenecks.

The Debsh Tea company scandal offers one glaring example. Between 2019 and 2022, Debsh Tea, a privately owned importer and producer, received billions of dollars in preferential foreign exchange earmarked for essential imports. In late 2023, Iranian oversight bodies and judiciary-linked reporting alleged that a significant portion of this subsidized currency was not used for the declared imports and was instead diverted into open-market transactions—turning access to cheap dollars into a quick profit by capturing the gap between the preferential and market exchange rates. The sums reported—upwards of $3 billion—was large enough to cover years of national tea demand or finance major public investment.

Not every case becomes a national headline, but the mechanism is familiar. Similar audit controversies have surfaced before, involving preferential access to foreign currency that did not match verified import records or any documented return of the money. One widely cited instance is the Supreme Audit Court dispute over $4.8 billion in preferential foreign exchange reportedly disbursed to importers with no corresponding imports documented.

When the resulting legitimacy crisis becomes intolerable, the state rolls out corrective packages presented as anti-corruption reforms. In practice, these policies entrench austerity and deliver sudden price shocks. Health policy offers a clear example. The Daroyar reform—a 2022 overhaul of drug subsidies—ended preferential foreign exchange for medicine and shifted the subsidy to an insurance-based reimbursement system. In theory, patients would pay less at the pharmacy while insurers and the state covered the difference. In practice, the financing chain never stabilized: Delayed reimbursements and liquidity shortages increased out-of-pocket costs and produced persistent gaps in access for patients and pharmacies alike. Meanwhile, the government captured fiscal gains from changes in the exchange rate, banks benefited as suppliers and importers relied more heavily on high-cost borrowing. Fuel policy has followed a similar pattern. Price hikes were justified as a way to fund targeted redistribution through cash transfers, but transfers quickly lagged behind high inflation, leaving households to absorb the widening gap between what they received and the real cost of fuel.

The broader state response to the sanctions driven fiscal crisis follows a familiar path. Rather than meeting its obligations through stable public funding, it has leaned on privatization, debt-for-asset swaps and “productive use” (Movaledsazi) schemes that transfer public assets into private hands. A notable example is the pension system. Instead of paying down its debt to Social Security in cash, the government has increasingly transferred shares in state-owned firms, effectively forcing the pension system to finance benefits through dividends, asset sales and investment returns. This policy shifts risk onto retirees by tying their livelihoods to market performance and inflation rather than stable entitlements.

The result is a sanctioned political economy in which austerity becomes a governing tool, and scarcity generates profit for those with privileged access. Instead of protecting households through social provision, so-called anti-corruption reforms shift the costs and risks downward through devaluation and subsidy removal while preserving the allocation systems that advantage well-connected elites. This pattern is widely noted in sanctions-era analyses of inequality and distribution. Recent official estimates put poverty at roughly a third of the population; similarly, the World Bank estimates that close to 10 million people fell into poverty over the past decade.

The result is a sanctioned political economy in which austerity becomes a governing tool, and scarcity generates profit for those with privileged access.

The downward redistribution is visible in how quickly economic shocks travel outward from the commercial core to outlying towns and provinces and in the forms of anger they produce. In western Iran’s long marginalized regions, in towns like Abdanan, the crisis has hit earlier and harder than in many central provinces, leaving deep underinvestment, high unemployment and entrenched poverty. During the recent protest wave, demonstrators stormed a supermarket and tore open bags of rice, scattering the grain across the floor and into the street rather than carrying it away. By late December, a 10kg bag of rice was selling for around several million toman, roughly equivalent to a month of minimum wage income. The gesture was not theft so much as refusal and a public rejection of a system that turns a basic staple into a luxury while demanding that people accept humiliation as everyday submission.

When crisis is managed through shock transfer rather than redistribution, policy becomes part of the problem, producing a vicious cycle. As economic instability intensifies, the state responds with new rounds of austerity framed as reform. Households do not experience these measures as repair; they experience them as a cost shift that deepens the crisis of everyday survival. The usual channels for complaint and mediation lose credibility. People can petition officials and institutions, but those same institutions are either implementing the damaging reforms or lack the power to reverse them. As that legitimacy erodes, pressure accumulates until a trigger can diffuse economic hardship into a national protest moment. Once dissent spills outside institutional channels, the state increasingly treats it as disorder. With fewer credible mechanisms of incorporation left, repression becomes routine because it is the only tool remaining to retain control.

External Signaling, Internal Escalation

When US and Israeli officials cast the protests as a theater of war and regime change, the state can more easily reframe mass dissent as a security threat and respond with counterinsurgency-style repression.

What has made this round of uprisings deadlier is the interplay between external and internal escalation. Iranians did not need outside encouragement to come to the streets: The currency collapse, unmatched wages to inflation and erosion of everyday survival were sufficient conditions for revolt. Rather, external escalation has raised the cost of dissent in a different way—less through material support than through narrative and signaling. When US and Israeli officials cast the protests as a theater of war and regime change, the state can more easily reframe mass dissent as a security threat and respond with counterinsurgency-style repression.

Exiled opposition figures, most prominently the wannabe king, Reza Pahlavi (son of Iran’s deposed Shah in the 1979 revolution) have tried to cast the uprising as a transition movement and have urged escalation, including repeated calls for foreign intervention to facilitate Pahlavi’s return as the national leader. At the same time, US and Israeli officials have publicly gestured at their own involvement, boasting of assets on the ground, speaking casually of arming protestors and promising “help is on the way.” Their posturing only serves to strengthen the state’s claim that dissent is a foreign operation. Iranian officials have in turn framed the protests as an extension of the 12-day war with Israel in June 2025.

The result is a two-sided narrative that benefits everyone except ordinary Iranians. On one side, external signaling transforms real popular dissent into a proxy battlefield where death becomes collateral damage on the road to regime change. On the other, the Islamic Republic treats all regime change rhetoric as proof that protestors are terrorists, spies and enemy assets rather than citizens with legitimate grievances. In this sense, the response of the Iranian state and the politics of external powers share a core feature: both treat Iranian lives as expendable for the needs of power and profit.

The protests may be suppressed for now, but the conditions that generated them remain unchanged. There is little evidence that the state is able or willing to undertake the structural and welfare reforms needed to fundamentally address the crisis of everyday survival. While it cannot directly lift sanctions, it has shown little interest in reducing household exposure to inflation, curbing precarious living conditions or rebuilding the minimum credibility of welfare and representation. Currency instability and price volatility are increasingly governed as normal conditions, not emergencies to be solved. With each turn of the cycle from austerity to protest, the crisis deepens and heavier force becomes the default method of control. What comes next is uncertain, but the direction is not. As long as crisis is managed through austerity and bullets, and as long as external powers treat Iranian lives as instruments of pressure and regime change, the costs will keep rising and more will die.

Ida Nikou holds a PhD in sociology from Stony Brook University.

Editor’s note: Due to the ongoing internet shutdown in Iran, some Iran-based websites were inaccessible at the time of publication. Links are nonetheless included for reference.

The Biggest Threats the Iranian People Face Are America and Israel

January 30, 2026

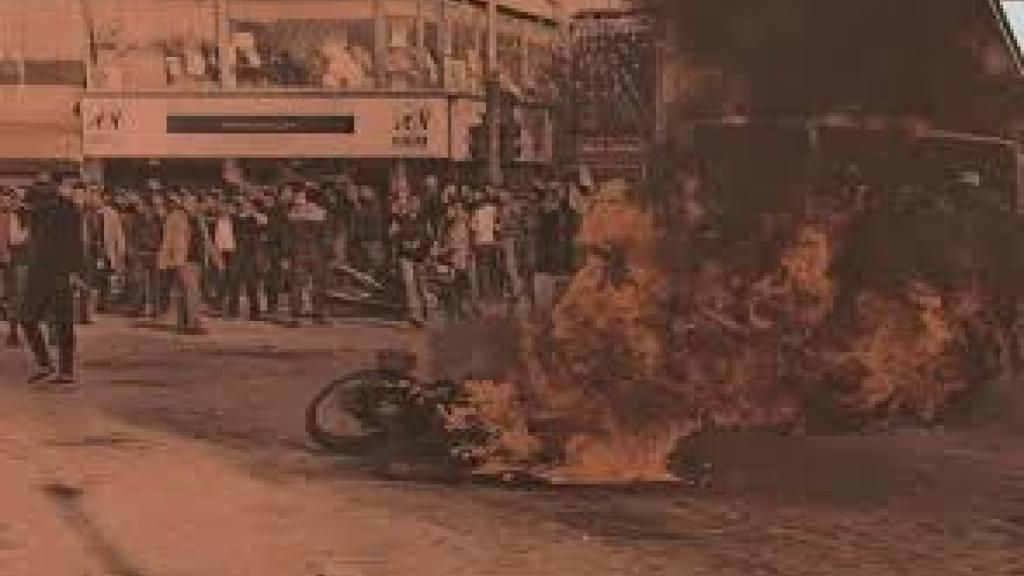

Demonstrator silhouetted against a street fire waving the Lion and Sun flag, 9 January 2026 – CC0

Israel’s longstanding campaign to lure Washington into war with Iran seems to have fizzled once again—for now, anyway. But in their attempt to invent a casus belli, their spy agencies employ tactics—disinformation, infiltration, and incitement of rioting—that help sustain the patently false impression that Tehran, not Tel Aviv, is home to the Middle East’s cruelest regime.

“We Are with You in the Field”

In late December, people in several cities across Iran took to the streets in nonviolent protest over the crushing economic conditions spawned by US attacks on Iran’s currency and the further intensification of US sanctions. Police were deployed, but the protests were peaceful, so they stayed on the sidelines.

Then, suddenly on January 8, shocking violence broke out across Iran, and most of the peaceable protesters vanished from the streets. They’d been displaced by young toughs, many of them armed.

Video (released by both government and anti-government forces) showed arsonists setting fire to businesses, mosques, a fire station (killing the firefighters inside), and other buildings, as well as public buses. Roving gangs, reportedly armed by Israeli agents, gunned down hundreds of people.

Max Blumenthal at The Grayzone reported,

“In Kermanshah, where anti-government rioters shot and killed 3 year-old Melina Asadi, groups of militants were filmed firing automatic weapons at police. In cities from Hamedan to Lorestan, rioters have filmed themselves beating unarmed security guards to death for attempting to impede their rampages.”

Suspecting foreign incitement, officials in Tehran shut off all internet connections beyond Iran’s borders. Sure enough, the violence ended as suddenly as it had started two days earlier.

There soon emerged more evidence that the riots had been orchestrated from abroad. Israel’s spy agency Mossad, which has many agents and collaborators on the ground in Iran, had put out the following message through its Farsi-language X account: “Go out together into the streets. (See especially Justin Podur’s Jan. 27 analysis, “The Iran Insurgency: A review of the available evidence”) The time has come. We are with you. Not only from a distance and verbally. We are with you in the field.” In an interview, Yoav Gallant, a former Israeli defense minister, was quite clear: “The regime in Iran must fall . . . At this moment, when what matters most is the mass action on the ground, we need to stay in the background and steer things with an invisible hand.“ Even former US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo got in on the action, posting, “Happy New Year to every Iranian in the streets … also, to every Mossad agent walking beside them.”

US sanctions had ruined Iran’s economy, bringing people into the streets in protest. Israel took it from there, using the nonviolent demonstrations over economic issues as cover for whipping up deadly riots against the government.

On January 20, speaking at the Davos World Economic Forum, US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent pulled back the curtain a bit more, boasting that the sanctions and currency manipulation inflicted on Iran had been highly successful, because “their economy collapsed,” so “people took to the streets” and now “things are moving in a very positive way.”

(Helena Cobban, president of the non-profit Just World Educational, has pointed out that Bessent was saying, in effect, that the Iran sanctions “were intended to inflict such harsh pain and misery on entire populations of civilians that those civilians take action to change their government.” And, she added, that fits the definition of state-sponsored terrorism. Israel’s role in converting peaceful protest into armed uprising was a further terrorist act.)

As the violence in Iran was peaking, Reza Pahlavi, son the last Shah of Iran, tweeted support for the riots from his place of exile in the Washington, DC suburbs: “Our goal is no longer merely to come to the streets; the goal is to prepare for seizing the centers of cities and holding them.” Pahlavi has longed to retake the throne in Iran ever since his father, a brutal tyrant, was overthrown in the revolution of 1979.

Image: Priti Gulati Cox.

Corporate media coverage of events in Iran has been abysmal—light on facts and heavy with Israeli propaganda. Social media were hijacked, too. Data analysis by the staff of Al Jazeera showed how a #FreeThePersianPeople hashtag that went viral during the riots

“…appears to be a politicized information operation constructed outside Iran and led by networks linked to Israel and its allies. The campaign successfully hijacked legitimate economic grievances, reframing them within a broader political project that links the ‘liberation of Iran’ to the return of the monarchy and foreign military intervention.”

Sina Toosi of the Center for International Policy wrote for The Nation that given Washington’s seemingly unlimited tolerance for the Israeli regime’s genocide in Gaza,

“What animates US and Israeli policy is not outrage at repression but hostility toward an adversarial state that resists their regional dominance … The claim that the United States has suddenly discovered a principled concern for Iranian lives is not merely implausible. It is an insult to the intelligence of anyone paying attention.”

Much of the American public does have sincere concern for the safety and wellbeing of the Iranian people. But the best way to help them is to demand that Washington end the sanctions on Iran, not instigate societal conflict and collapse.

Israel: The Bully’s Little Sidekick

The US and Israel have been trying and failing to topple Iran’s government for decades. But now, the Zionist regime is more tightly focused on Iran than ever. Its fraudulent “ceasefire” with the Palestinians, and its colonial “Board of Peace,” will simply be the final phase of the genocide, ending (in their fantasies, at least) with expulsion of all Palestinians from Gaza and the West Bank.

This last phase is to be quieter, more bureaucratic, than what came before—and managed by the US and some of its  other client regimes. The butchers in Tel Aviv hope they can then devote more of their own effort toward asserting dominance over the entire region. And that means taking down the government in Iran.

other client regimes. The butchers in Tel Aviv hope they can then devote more of their own effort toward asserting dominance over the entire region. And that means taking down the government in Iran.

Afraid to launch an all-out war against such a large, militarily powerful state, Washington and Tel Aviv have long bombarded the people of Iran with sanctions, financial attacks, propaganda, and psychological warfare, hoping to impose enough misery to spur a mass uprising capable of overturning the government. As Middle East Eye put it, they have sought “regime collapse without the costs of a direct military intervention”—with just a little exchange of bombs and missiles from time to time.

As recent events have shown, that was wishful thinking. Authentic protests in Iran remained nonviolent, and no one called for installation of the much-hated, much-ridiculed Reza Pahlavi as Iran’s leader. Clearly, external stoking of violence and chaos was required to convince the world that Iran is imploding, and that’s what we’ve now seen.

Israel and the US may be feeling their oats right now, but they have made themselves pariah nations with their genocide of the Palestinian people and their aggression against any society on any continent that refuses to comply with their neocolonial ambitions.

Polls show that the numbers of people around the world who hold negative views of Israel have risen dramatically. Last year, Pew found the regime to be 33 points underwater on that question, with 62% of responses unfavorable and 29% favorable. Pew also found a dramatic increase in unfavorable views of the United States, largely related to our economic, military, diplomatic, and media sponsorship of the genocide in Gaza.

For the past two years, Israel has ranked dead last among the world’s countries in the Nation Brands Index, a national-reputation score. Furthermore, institutions around the world are divesting from billions of dollars in Israel Bonds, which are essential to sustaining its economy. The global Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement against Israel is snowballing.

And crucially, writes Mohamad Elmasry, a professor at the Doha Institute for Graduate Studies,

“Gone, at least for now, are the days when Saudi Arabia viewed Iran as its foremost enemy, when Qatar saw Saudi Arabia as its principal threat, or when Egypt treated Qatar as the chief source of regional instability. Increasingly, Arab regimes, with perhaps the exception of the UAE, now view Israel as the region’s most destabilizing force.”

The loathing that most of the world has for Israel is richly earned. For many, the genocide—not only the raw death toll but also the sadistic relish with which the Zionist regime has tortured an entire society for the past 28 months—was the last straw.

The one element of the state that once drew the most respect, its much-vaunted military, has proven once and for all to be a pathetic fraud. The Israeli Occupation Forces are cowards. Against Iran, Syria, Yemen, Lebanon, Gaza, everyone, they attack mostly or entirely from afar, with shelling and bombing and drones and cyberattacks and, yes, beepers. They rely heavily on clean, safe, white-collar warfare: espionage, propaganda, and sabotage. But they’re picking fights they can’t finish.

When they have dared to engage in battle on the ground, as in Lebanon, they’ve been routed. Their troops’ attempts to invade, capture, and hold ground in Gaza also have been totally hapless failures, except during “ceasefires”, when only the Palestinian resistance ceases and only the IOF fires.

Then, whenever Israeli forces gin up the “courage” to bomb the elephant in the region, Iran, they usually act like a bully’s little sidekick: picking fights, then running and hiding behind Washington’s skirts, crying, “Save us, please!”

We Americans must accept that our government and its client Israel are rogue states. Together, they will continue posing a threat to the rest of the world until we force our own government to stop funding and start sanctioning Israel—and to end our own attacks, both military and economic, on other nations.

When US and Israeli officials cast the protests as a theater of war and regime change, the state can more easily reframe mass dissent as a security threat and respond with counterinsurgency-style repression.

What has made this round of uprisings deadlier is the interplay between external and internal escalation. Iranians did not need outside encouragement to come to the streets: The currency collapse, unmatched wages to inflation and erosion of everyday survival were sufficient conditions for revolt. Rather, external escalation has raised the cost of dissent in a different way—less through material support than through narrative and signaling. When US and Israeli officials cast the protests as a theater of war and regime change, the state can more easily reframe mass dissent as a security threat and respond with counterinsurgency-style repression.

Exiled opposition figures, most prominently the wannabe king, Reza Pahlavi (son of Iran’s deposed Shah in the 1979 revolution) have tried to cast the uprising as a transition movement and have urged escalation, including repeated calls for foreign intervention to facilitate Pahlavi’s return as the national leader. At the same time, US and Israeli officials have publicly gestured at their own involvement, boasting of assets on the ground, speaking casually of arming protestors and promising “help is on the way.” Their posturing only serves to strengthen the state’s claim that dissent is a foreign operation. Iranian officials have in turn framed the protests as an extension of the 12-day war with Israel in June 2025.

The result is a two-sided narrative that benefits everyone except ordinary Iranians. On one side, external signaling transforms real popular dissent into a proxy battlefield where death becomes collateral damage on the road to regime change. On the other, the Islamic Republic treats all regime change rhetoric as proof that protestors are terrorists, spies and enemy assets rather than citizens with legitimate grievances. In this sense, the response of the Iranian state and the politics of external powers share a core feature: both treat Iranian lives as expendable for the needs of power and profit.

The protests may be suppressed for now, but the conditions that generated them remain unchanged. There is little evidence that the state is able or willing to undertake the structural and welfare reforms needed to fundamentally address the crisis of everyday survival. While it cannot directly lift sanctions, it has shown little interest in reducing household exposure to inflation, curbing precarious living conditions or rebuilding the minimum credibility of welfare and representation. Currency instability and price volatility are increasingly governed as normal conditions, not emergencies to be solved. With each turn of the cycle from austerity to protest, the crisis deepens and heavier force becomes the default method of control. What comes next is uncertain, but the direction is not. As long as crisis is managed through austerity and bullets, and as long as external powers treat Iranian lives as instruments of pressure and regime change, the costs will keep rising and more will die.

Ida Nikou holds a PhD in sociology from Stony Brook University.

Editor’s note: Due to the ongoing internet shutdown in Iran, some Iran-based websites were inaccessible at the time of publication. Links are nonetheless included for reference.

Demonstrator silhouetted against a street fire waving the Lion and Sun flag, 9 January 2026 – CC0

Israel’s longstanding campaign to lure Washington into war with Iran seems to have fizzled once again—for now, anyway. But in their attempt to invent a casus belli, their spy agencies employ tactics—disinformation, infiltration, and incitement of rioting—that help sustain the patently false impression that Tehran, not Tel Aviv, is home to the Middle East’s cruelest regime.

“We Are with You in the Field”

In late December, people in several cities across Iran took to the streets in nonviolent protest over the crushing economic conditions spawned by US attacks on Iran’s currency and the further intensification of US sanctions. Police were deployed, but the protests were peaceful, so they stayed on the sidelines.

Then, suddenly on January 8, shocking violence broke out across Iran, and most of the peaceable protesters vanished from the streets. They’d been displaced by young toughs, many of them armed.

Video (released by both government and anti-government forces) showed arsonists setting fire to businesses, mosques, a fire station (killing the firefighters inside), and other buildings, as well as public buses. Roving gangs, reportedly armed by Israeli agents, gunned down hundreds of people.

Max Blumenthal at The Grayzone reported,

“In Kermanshah, where anti-government rioters shot and killed 3 year-old Melina Asadi, groups of militants were filmed firing automatic weapons at police. In cities from Hamedan to Lorestan, rioters have filmed themselves beating unarmed security guards to death for attempting to impede their rampages.”

Suspecting foreign incitement, officials in Tehran shut off all internet connections beyond Iran’s borders. Sure enough, the violence ended as suddenly as it had started two days earlier.

There soon emerged more evidence that the riots had been orchestrated from abroad. Israel’s spy agency Mossad, which has many agents and collaborators on the ground in Iran, had put out the following message through its Farsi-language X account: “Go out together into the streets. (See especially Justin Podur’s Jan. 27 analysis, “The Iran Insurgency: A review of the available evidence”) The time has come. We are with you. Not only from a distance and verbally. We are with you in the field.” In an interview, Yoav Gallant, a former Israeli defense minister, was quite clear: “The regime in Iran must fall . . . At this moment, when what matters most is the mass action on the ground, we need to stay in the background and steer things with an invisible hand.“ Even former US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo got in on the action, posting, “Happy New Year to every Iranian in the streets … also, to every Mossad agent walking beside them.”

US sanctions had ruined Iran’s economy, bringing people into the streets in protest. Israel took it from there, using the nonviolent demonstrations over economic issues as cover for whipping up deadly riots against the government.

On January 20, speaking at the Davos World Economic Forum, US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent pulled back the curtain a bit more, boasting that the sanctions and currency manipulation inflicted on Iran had been highly successful, because “their economy collapsed,” so “people took to the streets” and now “things are moving in a very positive way.”

(Helena Cobban, president of the non-profit Just World Educational, has pointed out that Bessent was saying, in effect, that the Iran sanctions “were intended to inflict such harsh pain and misery on entire populations of civilians that those civilians take action to change their government.” And, she added, that fits the definition of state-sponsored terrorism. Israel’s role in converting peaceful protest into armed uprising was a further terrorist act.)

As the violence in Iran was peaking, Reza Pahlavi, son the last Shah of Iran, tweeted support for the riots from his place of exile in the Washington, DC suburbs: “Our goal is no longer merely to come to the streets; the goal is to prepare for seizing the centers of cities and holding them.” Pahlavi has longed to retake the throne in Iran ever since his father, a brutal tyrant, was overthrown in the revolution of 1979.

Image: Priti Gulati Cox.

Corporate media coverage of events in Iran has been abysmal—light on facts and heavy with Israeli propaganda. Social media were hijacked, too. Data analysis by the staff of Al Jazeera showed how a #FreeThePersianPeople hashtag that went viral during the riots

“…appears to be a politicized information operation constructed outside Iran and led by networks linked to Israel and its allies. The campaign successfully hijacked legitimate economic grievances, reframing them within a broader political project that links the ‘liberation of Iran’ to the return of the monarchy and foreign military intervention.”

Sina Toosi of the Center for International Policy wrote for The Nation that given Washington’s seemingly unlimited tolerance for the Israeli regime’s genocide in Gaza,

“What animates US and Israeli policy is not outrage at repression but hostility toward an adversarial state that resists their regional dominance … The claim that the United States has suddenly discovered a principled concern for Iranian lives is not merely implausible. It is an insult to the intelligence of anyone paying attention.”

Much of the American public does have sincere concern for the safety and wellbeing of the Iranian people. But the best way to help them is to demand that Washington end the sanctions on Iran, not instigate societal conflict and collapse.

Israel: The Bully’s Little Sidekick

The US and Israel have been trying and failing to topple Iran’s government for decades. But now, the Zionist regime is more tightly focused on Iran than ever. Its fraudulent “ceasefire” with the Palestinians, and its colonial “Board of Peace,” will simply be the final phase of the genocide, ending (in their fantasies, at least) with expulsion of all Palestinians from Gaza and the West Bank.

This last phase is to be quieter, more bureaucratic, than what came before—and managed by the US and some of its  other client regimes. The butchers in Tel Aviv hope they can then devote more of their own effort toward asserting dominance over the entire region. And that means taking down the government in Iran.

other client regimes. The butchers in Tel Aviv hope they can then devote more of their own effort toward asserting dominance over the entire region. And that means taking down the government in Iran.

Afraid to launch an all-out war against such a large, militarily powerful state, Washington and Tel Aviv have long bombarded the people of Iran with sanctions, financial attacks, propaganda, and psychological warfare, hoping to impose enough misery to spur a mass uprising capable of overturning the government. As Middle East Eye put it, they have sought “regime collapse without the costs of a direct military intervention”—with just a little exchange of bombs and missiles from time to time.

As recent events have shown, that was wishful thinking. Authentic protests in Iran remained nonviolent, and no one called for installation of the much-hated, much-ridiculed Reza Pahlavi as Iran’s leader. Clearly, external stoking of violence and chaos was required to convince the world that Iran is imploding, and that’s what we’ve now seen.

Israel and the US may be feeling their oats right now, but they have made themselves pariah nations with their genocide of the Palestinian people and their aggression against any society on any continent that refuses to comply with their neocolonial ambitions.

Polls show that the numbers of people around the world who hold negative views of Israel have risen dramatically. Last year, Pew found the regime to be 33 points underwater on that question, with 62% of responses unfavorable and 29% favorable. Pew also found a dramatic increase in unfavorable views of the United States, largely related to our economic, military, diplomatic, and media sponsorship of the genocide in Gaza.

For the past two years, Israel has ranked dead last among the world’s countries in the Nation Brands Index, a national-reputation score. Furthermore, institutions around the world are divesting from billions of dollars in Israel Bonds, which are essential to sustaining its economy. The global Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement against Israel is snowballing.

And crucially, writes Mohamad Elmasry, a professor at the Doha Institute for Graduate Studies,

“Gone, at least for now, are the days when Saudi Arabia viewed Iran as its foremost enemy, when Qatar saw Saudi Arabia as its principal threat, or when Egypt treated Qatar as the chief source of regional instability. Increasingly, Arab regimes, with perhaps the exception of the UAE, now view Israel as the region’s most destabilizing force.”

The loathing that most of the world has for Israel is richly earned. For many, the genocide—not only the raw death toll but also the sadistic relish with which the Zionist regime has tortured an entire society for the past 28 months—was the last straw.

The one element of the state that once drew the most respect, its much-vaunted military, has proven once and for all to be a pathetic fraud. The Israeli Occupation Forces are cowards. Against Iran, Syria, Yemen, Lebanon, Gaza, everyone, they attack mostly or entirely from afar, with shelling and bombing and drones and cyberattacks and, yes, beepers. They rely heavily on clean, safe, white-collar warfare: espionage, propaganda, and sabotage. But they’re picking fights they can’t finish.

When they have dared to engage in battle on the ground, as in Lebanon, they’ve been routed. Their troops’ attempts to invade, capture, and hold ground in Gaza also have been totally hapless failures, except during “ceasefires”, when only the Palestinian resistance ceases and only the IOF fires.

Then, whenever Israeli forces gin up the “courage” to bomb the elephant in the region, Iran, they usually act like a bully’s little sidekick: picking fights, then running and hiding behind Washington’s skirts, crying, “Save us, please!”

We Americans must accept that our government and its client Israel are rogue states. Together, they will continue posing a threat to the rest of the world until we force our own government to stop funding and start sanctioning Israel—and to end our own attacks, both military and economic, on other nations.

MARINS: An American naval showdown with Iran will not go well for the US

In 2025, according to analyses from Kpler, Vortexa, and TankerTrackers, Venezuela, Iran and Russia supplied 35-40% of China's oil demand. In Russia’s case, it also met a third of China's natural gas demand.

As they are sanctioned countries, they operate with intermediaries, ship-to-ship transfers, and other opaque means to evade sanctions, which means in reality these countries probably meet 50% of China's demand.

All this oil is sold to the Chinese with discounts ranging from 10% to 20% and in special cases can reach 30%. That’s good business.

These purchases have helped boost the competitiveness of various Chinese sectors, mainly petrochemicals, producing naphtha and derivatives like ethene, propene, plastics (PE, PP), resins, solvents, and basic chemicals at highly competitive prices, with China dominating 40-50% of global petrochemical capacity, exporting plastics and chemicals at unbeatable prices, gaining market share in global markets (Asia, Africa, Latin America).

The cheap oil also directly impacts the costs of Chinese infrastructure and fuel refining, which gains billions of dollars.

In a world where the West has increasingly expensive energy, the Chinese government showed skill and made great deals, which further boosted Chinese competitiveness, something that the West now wants to end by force.

The hawks in Washington, after taking Venezuela off the board, authorized this week that Caracas sell oil to the Chinese, but they will set the price. This evidences one of the objectives until now little discussed by political and military analysts. The Maduro Operation to decapitate the Venezuela had less to do with promoting values of boosting democracy, but simply levelling the commercial playing field of competing US products in a market where China had won itself an unbeatable competitive price advantage.

With Venezuela out of the game, Washington is now turning its attention to Iran.

If the Persians have a similar end to the Venezuelans, this will impact the competitiveness of the Chinese industry, which will then depend exclusively on cheaper Russian oil and thus have greater difficulties in getting discounts. The Chinese also have a 10,400-kilometre railway creating a corridor directly linking China and Iran that became operational in mid-2025, traversing Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan to connect Xi’an with Tehran. The advantage of the rail link is it is impervious to pressure by the US navy.

The relationship between the Chinese and Iran involves military, energy, and many mineral issues, since Persian lands house something between 7-10% of the planet's mineral reserves.

The contradictory thing is that these discounts only exist because the West imposed sanctions on these countries and only now realized that with this it was favouring its biggest rival: China. Many critics argue that the West no longer has the power of decades ago to decide the shine or ostracism of a nation through the sanctions mechanism in an increasingly multipolar world.

Although American hawks are targeting the cheap supply to the Chinese, militarily any action against Iran will be a great challenge.

Although Iran has an irrelevant air force, war at sea deeply favours them. Iranian anti-ship missiles like the Qadr-474 have a range of up to 2,000 km, which is 8x the average of European missiles and 30% greater than the maritime version of the Tomahawk. In terms of developing naval anti-ship munitions, the US has been asleep at the wheel. This without mentioning thousands of UAV drones, USVs, and UVVs for which Iran is one of the world leaders. The US has been napping on the development of drone technology too.

A direct attack on Iran could close the Strait of Hormuz, where one-third of the world’s seaborne oil trade, and almost one-fourth of its LNG passes. That would throw oil prices sky high, widely favouring the Russians.

And if Iran decides to close the strait, this will be something long thought over, done with the stock of 5,000 sea mines and 20-23 mini submarines equipped with special torpedoes and submerged-launched Jask-2 anti-ship missiles, besides long range cruise anti-ship missiles that equip other 6-7 larger submarines. Iran even has three Kilo-class Russian-made submarines with a stealth range of 300km during which they are virtually undetectable.

With a fleet that even counts the destroyer Sahand and other 25-30 frigates, corvettes, and patrol boats, all equipped with missiles, the Iranian navy can impose a combat of many months in the strait.

Another great peril posed by this navy is its mosquito fleet of catamarans and fast boats equipped with missiles and some even with anti-air defence systems. Just in 2020, Iran commissioned 100 of these vessels.

A second strike group is being sent to the region, with the intent to reinforce the American fleet, which already has about 1,000 Vertical Launch System (VLS), but still below the 1,600-2,000 launchers present in the Iranian navy. Again, I emphasize that a battle at sea favours the Iranians, while the massive use of planes greatly favours the Americans. It will be a battle mainly of two different doctrines: large ships composing a navy to project power, facing a navy focused on low cost, in the Mosquito strategy.

Iran is a nation of 90mn people and one of the top 5 in drone and missile technology. And the Americans will have a challenge ahead, which is to break through the Iranian naval defences at a time when Tehran is in survival mode and will probably fight with everything it has.

Iran ‘Unlikely To Capitulate’ To Trump’s Demands For A Deal To Avoid Military Action

January 30, 2026

RFE RL

By Kian Sharifi

Even as US President Donald Trump threatens to strike Iran, he has repeatedly called on Tehran to “make a deal.”

Trump’s demands for an agreement are clear: Iran must end its nuclear program, limit its ballistic missile capabilities, and sever ties with armed proxies in the Middle East. In return, the United States will not attack Iran and remove crippling sanctions.

If the Islamic republic does not accept those terms, Trump has warned that the country will suffer consequences “far worse” than last year, when the United States joined Israel in bombing Iran’s nuclear sites.

Experts say it is unlikely that Iran will accept Trump’s maximalist demands, which would mark a reversal of decades of policy and amount to capitulation in the eyes of Tehran.

‘Before It’s Too Late’

In written comments sent to RFE/RL, a White House official said Trump “hopes that no action will be necessary” against Iran but urged Tehran to make a deal “before it is too late.”

Trump has “demonstrated with Operation Midnight Hammer and Operation Absolute Resolve that he means what he says,” said the official, referring to the June 2025 strikes on Iran’s nuclear sites and the US operation that ousted Venezuelan leader Nicolas Maduro on January 3.

“The President has a wide array of options at his disposal to address the situation in Iran,” added the White House official.

The United States has deployed key military assets, including an air carrier and additional bombers, to the Middle East in recent days.

Trump has also ratcheted up economic pressure on Tehran by announcing a 25 percent tariff on any country doing business with Iran and imposing new sanctions.

The US president has threatened to carry out a military strike on Iran since nationwide protests erupted in late December 2025 and the authorities launched a violent crackdown that killed thousands of demonstrators.

US Military Action Is ‘Likely’

Trump on January 28 said he wanted a “fair and equitable deal” that ensured Iran will have “no nuclear weapons.” Tehran has long claimed that its nuclear program is peaceful.

But the nuclear file is only one of several US demands. Trump, according to reports, has also insisted that Iran must accept caps on its ballistic missile program and end its support for pro-Iranian armed groups in Lebanon, Iraq, Yemen, and the Palestinian territories.

Tehran possesses short-range missiles that threaten US military bases and commercial interests in the Persian Gulf and advanced medium-range missiles that can reach Israel, a key US ally.

Experts say Trump is seeking to exploit the unprecedented weakness of Iran’s clerical establishment to force Tehran into making wide-ranging concessions.

Iran’s rulers have been weakened by a worsening economic crisis and weeks of nationwide protests that posed the biggest threat to their power in years. Israel has also degraded the military capabilities of Tehran’s allies, including Lebanon’s Hezbollah, Yemen’s Huthi rebels, and US-designated Palestinian terrorist group Hamas.

“Some US officials see this moment as an opportunity to pressure Tehran into concessions on nuclear limits, regional behavior, and missile capabilities,” said Alex Vatanka, Iran program director at the Washington-based Middle East Institute.

‘Collapse Of The Islamic Republic’

Iranian officials, including Foreign Minister Abbas Araqchi and parliament speaker Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, have said Tehran is open to talks but alleged Washington is not interested in a fair agreement.

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei would be “very skeptical and resistant to accept” Trump’s demands “as he would perceive acceding to them as paving the way for the collapse of the Islamic republic,” said Jason Brodsky, policy director at the Washington-based United Against Nuclear Iran.

In the absence of a deal, Trump is “very likely” to authorize military action against Iran, said Brodsky, pointing to the president’s rhetoric and the US military buildup in the region.

“This is a very similar pattern of statements and actions that resulted in the 12-day war in June and the US seizure of Nicolas Maduro in Venezuela,” he said. “President Trump alternates between confrontational and conciliatory statements to throw the Iranian regime off.”

Brodsky said the objectives of military action would be to hold Iran accountable for its bloody crackdown on protesters, deter its behavior in the region, and erode its military capabilities.

He added Trump could view “further military action as the prelude to an eventual deal down the line.”

Vatanka offered a more cautious assessment, arguing there are “still reasons for the United States to think twice.”

He emphasized that “the Pentagon knows any strike could trigger a regional chain reaction” involving Iran’s allied armed groups and proxies.

The US military buildup in the Middle East, he suggested, could be “mostly defensive or aimed to pressure Tehran on the diplomatic track, rather than [bring about] regime change.”

The Iranian Protests Explained – OpEd

January 30, 2026

By Daniel Falcone

In this interview, international relations scholar Stephen Zunes and Middle East historian Lawrence Davidson help to unpack the Iranian protests and explain their relevance within the context of U.S. and Israeli national interests.

Daniel Falcone: Jeffrey St. Clair of CounterPunch, recently cited filmmaker Jafar Panahi’s insistence that change in Iran must come from the will of the people, not from outside intervention. As U.S. and Israeli involvement tends to strengthen hardliners, how do you explain the balance between international solidarity and the risk of external actors undermining Iran’s sovereignty and social movement?

Lawrence Davidson: One has to ask what these terms, international solidarity, and risk from external actors, mean in today’s international environment. If international solidarity means, for instance, the solidarity of reactionary countries that have somehow made an alliance to change the internal behavior of a third nation, that is obviously problematic. In this case, international solidarity is the manifestation of just these external actors. If the United States intervenes in Iran at this time, it would not be to the benefit of the Iranian people, it would be for the suppression of anti-Zionist sentiment in the country through the introduction of the Shah’s adult son. This would probably lead to something like a civil war in Iran. If, however, international solidarity means the sentiment of people rather than governments, this has not proved very effective, as we can see in the case of Gaza.

The Arab and Muslim peoples have either chosen not to or could not in any practical way act to support the Palestinians. I’m afraid that the conclusion here is that in the present circumstances, there is no balance between international solidarity and external actors. The power of institutionalized external actors overwhelms practical terms, the power of popular solidarity.

Stephen Zunes: While the United States and Israel have tried to take advantage of the unrest, the protests this round, as well as previously, have been homegrown and not the result of imperialist machinations. Iran has had a long history of widespread civil resistance going back to the late nineteenth century with the tobacco strike against imperialist economic domination, through the Constitutional Revolution the following decade, through the revolution in the late 1970s that brought down the U.S.-backed Shah. The outspoken support for the protests by the U.S. and Israeli governments have probably been counter-productive, feeding the regime’s false narrative that they are a result of foreign backing. Israel and the United States have a lot of power in terms of blowing things up and killing people.

They do not have the power to get hundreds of thousands of angry Iranians into the streets or even to steer the direction of their protests. The people who have given their lives on the streets were fighting for their freedom, not for foreign powers. Threats of military action by the United States and Israel have also likely strengthened the regime, since people tend to rally around the flag in case of outside threats and most Iranians across the political spectrum do not trust either country.

Given the U.S. support for even more repressive regimes in the Middle East, don’t think the Trump administration cares about the Iranian people. Bombing Iran to ostensibly support the uprising would be a tragedy. People would certainly be reluctant to go out onto the streets while they are being bombed. Most of those calling for U.S. military intervention appear to have been from the Iranian diaspora, not those on the streets. Although some Iranians within the country may have been desperate enough to want to risk it as well, let’s remember that it was not the eleven weeks of NATO bombing that brought down Milosevic in Serbia. It was the massive nonviolent resistance of the Serbian people that took place more than a year later.

It is possible that the United States and Israel might prefer the current reactionary, autocratic Iranian regime to a democratic one, which would still be anti-hegemonic and anti-Zionist but have a lot more credibility. A democratic Iran would still be nationalistic and sympathetic to the Palestinian cause, but less likely to engage in the kinds of repression and provocative foreign policies that would give the United States and Israel an excuse for some of their militarism. Solidarity from global civil society, by contrast, is important and appropriate. Despite claims by some to the contrary, many prominent pro-Palestinian voices from Bernie Sanders to Peter Beinart to Greta Thunberg have been outspoken in their support for the Iranian popular struggle as well. People will certainly tend to protest more when their own governments are actively supporting repression and mass killing, as with Israeli violence in Gaza and the West Bank, than when their governments are opposing the repression and mass killing.

Same as during the Cold War—it is quite natural for Americans to be less involved in protesting Communist repression we could do little about than repressive rightwing governments backed by Washington, where we might have more impact. As a result, this line about “where are all the protests on U.S. campuses?” has been unfair (particularly since most were still on winter break). And although some sectarian leftists really have become apologists for the reactionary Iranian regime or have exaggerated the Israeli role in the uprising, they are fortunately a small minority.

Ultimately, international solidarity is important, but it must be from sources that genuinely support the principles for which a popular movement is struggling. The movement in Iran, as with similar movements against autocratic regimes elsewhere, is fighting for freedom, democracy, and social and economic justice. Since neither the U.S. nor the Israeli government supports those principles, the Iranian regime—quite accurately in this case—can observe that U.S. and Israeli backing of the resistance is about advancing U.S. and Israeli strategic objectives, since these right-wing governments support regimes with even worse human rights records and they themselves are undermining democratic principles in their own countries. Indeed, some statements of support have played right into the regime’s hands.

Daniel Falcone: It seems that the participation of bazaaris and the poor and working class makes these protests distinct from earlier movements dominated by students and the middle class. How does this class composition alter legitimacy and the political stakes for the regime?

Lawrence Davidson: Their participation reflects the economic circumstances now. Those circumstances are, in turn, the product of externally imposed economic sanctions and incompetent internal management. Certainly, the participation of the bazaar keepers and the poor and working class in the protests is significant. No matter who comes out on top here, you’re going to see some sort of reform take place. The probability that it is the government that comes out on top is a function of the remaining loyalty of various contingents of the military. And a lot of this has to do with the economic stake of the Revolutionary Guard Corps in the status quo. As long as the military components of the regime stay loyal, the addition of bazaar keepers and the lower classes in the demonstrations cannot change the government.

Stephen Zunes: I find it rather significant that the bazaaris, traditionally a backbone of support for the regime, have been in the leadership of the resistance, as is the fact that there has been significant poor and working-class participation in the protests, unlike some previous movements, which have been disproportionately students and those from the educated middle class. The Iranian military, like the military in Egypt and some other autocratic systems, has their fingers in all sorts of economic enterprises at the expense of the common people. As a result, their brutal response to the protests was not just ideological, but from a desire to protect their vested interests.

It is also striking how quickly the protests went beyond economic issues. Most Iranians want at minimum much greater democratization/accountability within the current system and an increasing number clearly want regime change, not just because of economic hardship, but because they are simply tired of the repression.

Daniel Falcone: Although U.S. led sanctions have crippled Iran, there are also problems of systemic corruption and mismanagement by the Iranian state. Protesters increasingly reject both. Do you see this moment as one in which economic grievances lead to demands for democratization?

Lawrence Davidson: The economic problems come from both factors you mention. The Iranian theologians did not understand the intricacies of modern economic institutions or the importance of international trade. Thus, they could not manage a national economy, particularly one under outside stress. At the same time, American sanctions were designed to destroy that economy and impoverish the Iranian people. The two factors, working simultaneously, opened the way for corruption. And then there is the Revolutionary Guard capturing control of important parts of the economy. It is a mess. Democracy? I think we are a long way from that. We are probably closer to a military coup with the mullahs kept as front men.

Stephen Zunes: U.S.-led sanctions are unjustifiable (since Iran was honoring the nuclear agreement when Trump reimposed them) and they are hurting the economy. But my sense is that both the regime and Washington, for different reasons, are exaggerating the importance of the sanctions in sparking the rebellion. It is the regime’s corruption, mismanagement, and lack of accountability that are the bigger problems. The sanctions have provided the government with an excuse to deflect attention from their lousy economic policies, but that justification is now wearing thin. The economic problems are systemic, so changes at the Central Bank and minor adjustments in fiscal policies will not satisfy most protesters. The regime’s crony capitalism is being seen increasingly as beyond repair under the current system.

Daniel Falcone: UBC Professor Jaleh Mansoor eloquently defended the circulation of protest images as a form of democratic solidarity, while also warning about reactionary diaspora fantasies that reduce Iran’s future to either the Islamic Republic or a restored monarchy. How do you see media circulation distorting an understanding of the protests?

Lawrence Davidson: I do believe that the images should be shown as widely as possible, just as should the ones from Gaza. However, the problem is that they are often shown with either few or misleading explanations. Western commentators do not understand much of the context of happenings in Iran, much less the history. This is the price of a corporate press. The ignorance and biases of editors, if not reporters, are shown over and over. In our lifetime the best example is during Vietnam.

Unless one is motivated to go to an alternate, more accurate source one will get a distorted picture. It is a curse that has always been with us. The wealthy Iranians in California can be as delusional as they wish but there will be no restored monarchy short of an American invasion and occupation of Iran. That is not going to happen. Thus, the Shah’s son will stay in LA.

Stephen Zunes: The greater the circulation of imagery of the people’s resistance and the regime’s repression the better. Care should be given as to how they are presented, however. Like protest coverage elsewhere, the media tends to disproportionately show dramatic photos of vandalism and arson even though overall the protests have been overwhelmingly nonviolent. Indeed, violence is used by the regime to increase its already horrific repression even more.

Similarly, the monarchists are certainly a small minority of the protesters, though both the regime and the Western media (for different reasons) like to highlight them. Although there is something of a nostalgia among better-off Iranians from the pre-revolutionary days—like there is by some Russians for the Soviet era—it is more of a sign of how bad things are now than how good things were then. The Shah was one of the most repressive dictators in the world, and the inequality and corruption under his rule was terrible. Despite some protesters with signs or chants calling for a return of the Shah, the reality is that most Iranians on the streets in recent weeks have been fighting for democracy. In addition to the small number of monarchists, there have also been communists, moderate Islamists, secular liberals, and lots of other folks. People are fed up. Based on my time in Iran a few years ago and my following the situation in that country for decades, I can say with confidence that most of the Iranian people are both anti-regime and anti-monarchist.

Daniel Falcone: Masoud Pezeshkian has taken a conciliatory tone. Are hardliners likely to prevail if the protests intensify? And do you see any viable path for change within the current system?

Lawrence Davidson: There is a story going around that some government people went to the University of Tehran. They asked the protesting students what they wanted. The answer was “we want you to leave.” This was a mistake on the part of the protesters. They gave those with more power than themselves, no way to retreat. I see no path to meaningful change. I do think that once the government retakes the streets, there will be minor positive alterations in their behavior.

Stephen Zunes: Pezeshkian is a relative moderate, but he is not nearly as powerful as the mullahs or the military. Iran’s authoritarian system is a series of complex overlapping loci of power which represent varying interests, unlike some authoritarian regimes centered around a single autocrat, whose social base is thinner. As a result, I am not surprised, though quite disappointed, that the regime appears to have successfully and violently suppressed another round of protests.

Another problem is that the Iranian regime is the first government to face a massive civil insurrection that initially came to power themselves through a massive civil insurrection. Just as regimes that have come to power through guerrilla warfare are better at engaging in counterinsurgency, the Islamic Republic has unfortunately developed better mechanisms than did the Shah (or Mubarak, Ben Ali, Milosevic, Marcos, Suharto, etc.) to suppress civil resistance. I do believe the regime’s days are numbered, however. I just can’t say when or predict what will replace it.

Daniel Falcone

Daniel Falcone is a historian, teacher and journalist. In addition to Foreign Policy in Focus, he has written for The Journal of Contemporary Iraq & the Arab World, The Nation, Jacobin, Truthout, CounterPunch, and Scalawag. He resides in New York City and is a member of The Democratic Socialists of America.

January 30, 2026

By John P. Ruehl

The plunge of Iran’s rial has resulted in nationwide protests exposing deep economic and social grievances. Exile groups and foreign powers are quietly testing Tehran’s strength amid its weakest point since the 1979 revolution.

In early January, several currency trackers briefly displayed the Iranian rial’s value as “$0.00,” unable to process the speed and scale of the depreciation, making it unexchangeable on important international trading platforms. The fallout quickly translated into a protest in Teheran’s bazaar district and eventually led to a mass unrest.