THE HAGFISH

Researchers sequence the first genome of myxini, the only vertebrate lineage that had no reference genome

Such finding, published in ‘Nature Ecology & Evolution’, is the work of an international consortium of more than 30 institutions from 7 countries around the world

VIDEO:

AN INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC TEAM MADE UP OF MORE THAN 40 AUTHORS FROM SEVEN DIFFERENT COUNTRIES, LED BY THE RESEARCHER AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MALAGA JUAN PASCUAL ANAYA, HAS MANAGED TO SEQUENCE THE FIRST GENOME OF THE MYXINI –ALSO KNOWN AS ‘HAGFISH’–, THE ONLY LARGE GROUP OF VERTEBRATES FOR WHICH THERE WAS NO REFERENCE GENOME OF ANY OF ITS SPECIES YET.

view moreCREDIT: UNIVERSITY OF MALAGA

An international scientific team made up of more than 40 authors from seven different countries, led by the researcher at the University of Malaga Juan Pascual Anaya, has managed to sequence the first genome of the myxini –also known as ‘hagfish’–, the only large group of vertebrates for which there was no reference genome of any of its species yet.

This finding, published in the scientific journal ‘Nature Ecology & Evolution’, has allowed deciphering the evolutionary history of genome duplications –number of times a genome is completely duplicated– that occurred in the ancestors of vertebrates, a group that comprises the human beings.

“This study has important implications in the evolutionary and molecular field, as it helps us understand the changes in the genome that accompanied the origin of vertebrates and their most unique structures, such as the complex brain, the jaw and the limbs”, explains the scientist of the Department of Animal Biology of the UMA Pascual Anaya, who has coordinated the research.

Thus, this study, which has taken almost a decade, has been carried out by an international consortium that includes more than 30 institutions from Spain, United Kingdom, Japan, China, Italy, Norway and the United States, including the University of Tokyo, the Japan research institute RIKEN, the Chinese Academy of Science and the Centre for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona, among others.

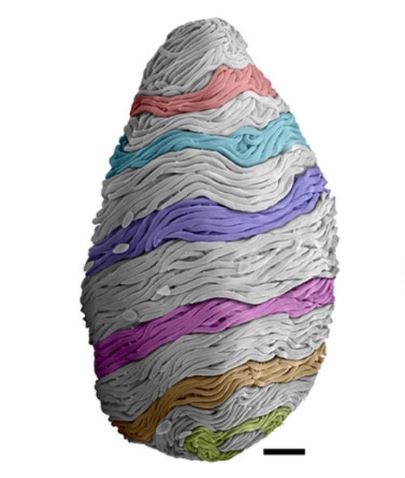

Ecological link

The myxini or ‘hagfish’ are a group of animals that inhabit deep ocean areas. Known for the amount of mucosa they release when they feel threatened –a focus of research of cosmetic companies– and, also, for their role as an ecological link in the seabed –since they are scavengers and are responsible for eliminating, among other things, the corpses of whales that end up at the bottom of the sea after dying–; hitherto their genome had not been sequenced due to its complexity, since they are composed of a large number of microchromosomes, which, in turn, are composed of repetitive sequences. This is in addition to the difficulty of accessing biological material.

“Besides, these microchromosomes are lost during the development of the animal, so that only the genital organs maintain a whole genome,” says Juan Pascual Anaya.

Genome duplications

To be more specific, for this study, in collaboration with the Chinese Academy of Science, the genome that has been sequenced is that of the Eptatretus burgeri, which lives in the Pacific, on the coasts of East Asia. To achieve this, the researchers generated data up to 400 times the size of its genome, using advanced techniques –Hi-C– of chromosomal proximity and managing to assemble it at chromosome level.

“This is important because it allowed us to compare, for example, the order of genes between this and the rest of vertebrates, including sharks and humans, and, thus, solve one of the most important open debates in genomic evolution: the number of genome duplications, and when these occurred during the origin of the different vertebrate lineages,” says the UMA scientist, who adds that thanks to this we now know that the common ancestor of all vertebrates derived from a species which genome was completely duplicated once.

Later, according to Pascual Anaya, the lineages that gave rise to modern mandibular and non-mandibular vertebrates separated, and each of these re-multiplied its genome independently: while the former, which include humans, duplicated it, the latter tripled it.

Evolutionary impact

An analysis of the functionality of genomes, based on extremely rare samples of myxini embryos, carried out in the prestigious laboratory of Professor Shigeru Kuratani of RIKEN; and a study on the possible impact of genome duplications on each vertebrate, developed together with the Professor at the University of Bristol and member of the Royal Society Phil Donoghue, complete this multidisciplinary research that is key to understanding the evolutionary history of vertebrates, since it provides perspectives on the genomic events that, probably, drove the appearance of important characteristics of vertebrates, such as brain structure, sensory organs or neural crest cells, among them, an increase in regulatory complexity, that is, a greater number of switches that turn genes on/off.

Juan Pascual Anaya is a scientist of the Department of Animal Biology of the University of Malaga. He studies the evolution of innovative structures that appear in different animal lineages, mainly vertebrates, for example, blood cells and the process by which they are produced, as well as other structures such as the origin of legs, hands or jaws.

He holds a degree in Biology from the University of Malaga and a PhD in Genetics from the University of Barcelona (2010). He held a postdoctoral position for 5 years, until 2015, at the RIKEN center in Japan, in the laboratory of Professor Shigeru Kuratani, where he became independent as a Permanent Scientific Researcher until 2021, year in which he returned to the UMA as a senior researcher of the ‘Beatriz Galindo’ grant program.

To be more specific, for this study, in collaboration with the Chinese Academy of Science, the genome that has been sequenced is that of the Eptatretus burgeri, which lives in the Pacific, on the coasts of East Asia. To achieve this, the researchers generated data up to 400 times the size of its genome, using advanced techniques –Hi-C– of chromosomal proximity and managing to assemble it at chromosome level.

An international scientific team made up of more than 40 authors from seven different countries, led by the researcher at the University of Malaga Juan Pascual Anaya, has managed to sequence the first genome of the myxini –also known as ‘hagfish’–, the only large group of vertebrates for which there was no reference genome of any of its species yet.

An international scientific team made up of more than 40 authors from seven different countries, led by the researcher at the University of Malaga Juan Pascual Anaya, has managed to sequence the first genome of the myxini –also known as ‘hagfish’–, the only large group of vertebrates for which there was no reference genome of any of its species yet.

An international scientific team made up of more than 40 authors from seven different countries, led by the researcher at the University of Malaga Juan Pascual Anaya, has managed to sequence the first genome of the myxini –also known as ‘hagfish’–, the only large group of vertebrates for which there was no reference genome of any of its species yet.

An international scientific team made up of more than 40 authors from seven different countries, led by the researcher at the University of Malaga Juan Pascual Anaya, has managed to sequence the first genome of the myxini –also known as ‘hagfish’–, the only large group of vertebrates for which there was no reference genome of any of its species yet.

CREDIT

University of Malaga

University of Malaga

It expands by 10,000 times in a fraction of a second, it’s 100,000 times softer than Jell-O, and it fends off sharks and Priuses alike.

By Ed Yong

JANUARY 23, 2019

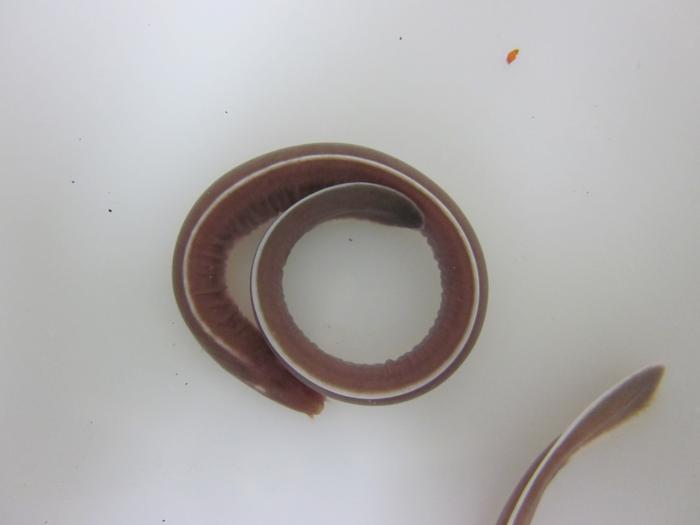

At first glance, the hagfish—a sinuous, tubular animal with pink-grey skin and a paddle-shaped tail—looks very much like an eel. Naturalists can tell the two apart because hagfish, unlike other fish, lack backbones (and, also, jaws). For everyone else, there’s an even easier method. “Look at the hand holding the fish,” the marine biologist Andrew Thaler once noted. “Is it completely covered in slime? Then, it’s a hagfish.”

Hagfish produce slime the way humans produce opinions—readily, swiftly, defensively, and prodigiously. They slime when attacked or simply when stressed. On July 14, 2017, a truck full of hagfish overturned on an Oregon highway. The animals were destined for South Korea, where they are eaten as a delicacy, but instead, they were strewn across a stretch of Highway 101, covering the road (and at least one unfortunate car) in slime.

Typically, a hagfish will release less than a teaspoon of gunk from the 100 or so slime glands that line its flanks. And in less than half a second, that little amount will expand by 10,000 times—enough to fill a sizable bucket. Reach in, and every move of your hand will drag the water with it. “It doesn’t feel like much at first, as if a spider has built a web underwater,” says Douglas Fudge of Chapman University. But try to lift your hand out, and it’s as if the bucket’s contents are now attached to you.

The slime looks revolting, but it’s also one of nature’s more wondrous substances, unlike anything else that’s been concocted by either evolution or engineers. Fudge, who has been studying its properties for two decades, says that when people first touch it, they are invariably surprised. “It looks like a bunch of mucus that someone just sneezed out of their nose,” he says. “That’s not at all what it’s like.”

For a start, it’s not sticky. If there wasn’t so damn much of it, you’d be able to wipe it off your skin with ease. The hagfish themselves scrape the slime off their skin by tying a knot in their bodies and sliding it from head to tail.

The slime also “has a very strange sensation of not quite being there,” says Fudge. It consists of two main components—mucus and protein threads. The threads spread out and entangle one another, creating a fast-expanding net that traps both mucus and water. Astonishingly, to create a liter of slime, a hagfish has to release only 40 milligrams of mucus and protein—1,000 times less dry material than human saliva contains. That’s why the slime, though strong and elastic enough to coat a hand, feels so incorporeal.

Indeed, it’s one of the softest materials ever measured. “Jell-O is between 10,000 and 100,000 times stiffer than hagfish slime,” says Randy Ewoldt from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, who had to invent new methods for assessing the substance’s properties after conventional instruments failed to cope with its nature. “When you see it in a bucket, it almost still looks like water. Only when you stick your hand in and pick it up do you find that it’s a coherent thing.”

The proteins threads that give the slime cohesion are incredible in their own right. Each is one-100th the width of a human hair, but can stretch for four to six inches. And within the slime glands, each thread is coiled like a ball of yarn within its own tiny cell—a feat akin to stuffing a kilometer of Christmas lights into a shoebox without a single knot or tangle. No one knows how the hagfish achieves this miracle of packaging, but Fudge just got a grant to test one idea. He thinks that the thread cells use their nuclei—the DNA-containing structures at their core—like a spindle, turning them to wind the growing protein threads into a single continuous loop.

Once these cells are expelled from the slime glands, they rupture, releasing the threads within them. Ewoldt’s colleague Gaurav Chaudhury found that despite their length, the threads can fully unspool in a fraction of a second. The pull of flowing water is enough to unwind them. But the process is even quicker if the loose end snags on a surface, like another thread, or a predator’s mouth.

Being extremely soft, the slime is very good at filling crevices, and scientists had long assumed that hagfish use it to clog the gills of would-be predators. That hypothesis was only confirmed in 2011, when Vincent Zintzen from the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa finally captured footage of hagfish sliming conger eels, wreckfish, and more. Even a shark was forced to retreat, visibly gagging on the cloud of slime in its jaws.

“We were blown away by those videos,” Fudge says, “but when we really looked carefully, we noticed that the slime is released after the hagfish is bitten.” So how does the animal survive that initial attack? His colleague Sarah Boggett showed that the answer lies in their skin. It’s exceptionally loose, and attaches to the rest of the body at only a few places. It’s also very flaccid: You could inject a hagfish with an extra 40 percent of its body volume without stretching the skin. The animal is effectively wearing a set of extremely loose pajamas, Fudge says. If a shark bites down, “the body sort of squishes out of the way.”

That ability makes hagfish not only hard to bite, but also hard to defend against. Calli Freedman, another member of Fudge’s team, showed that these animals can wriggle through slits less than half the width of their bodies. In the wild, they use that ability to great effect. They can hunt live fish by pulling them out of sandy burrows. And if disturbed by predators, they can dive into the nearest nook they find. Perhaps that’s why, in 2013, the Italian researcher Daniela Silvia Pace spotted a bottlenose dolphin with a hagfish stuck in its blowhole.

More commonly, these creatures burrow into dead or dying animals, in search of flesh to scavenge. They can’t bite; instead, they rasp away at carcasses with a plate of toothy cartilage in their mouths. The same traveling knots they use to de-slime themselves also help them eat. They grab into a cadaver, then move a knot from tail to head, using the leverage to yank out mouthfuls of meat. They can also eat by simply sitting inside a corpse, and absorbing nutrients directly through their skin and gills. The entire hagfish is effectively a large gut, and even that is understating matters: Their skin is actually more efficient at absorbing nutrients than their own intestines.

Hagfish are so thoroughly odd that biologists have struggled to clearly work out how they’re related to other fish, and to the other backboned vertebrates. Based on their simple anatomy, many researchers billed the creatures as primitive precursors to vertebrates—an intermediate form that existed before the evolution of jaws and spinal columns.

But a new fossil called Tethymyxine complicates that story. Hailing from a Lebanese quarry, and purchased by researchers at a fossil show in Tucson, Arizona, the Cretaceous-age creature is clearly a hagfish. It has a raspy cartilage plate in its mouth, slime glands dotting its flanks, and even chemicals within those glands that match the composition of modern slime. By comparing Tethymyxine to other hagfish, Tetsuto Miyashita from the University of Chicago concluded that these creatures (along with another group of jawless fish, the lampreys) are not precursors to vertebrates, but actual vertebrates themselves.

Such work is always contentious, but it fits with the results of genetic studies. If it’s right, then hagfish aren’t primitive evolutionary throwbacks at all. Instead, they represent a lineage of vertebrates that diverged from all the others about 550 million years ago, and lost several traits such as complex eyes, taste buds, scales, and perhaps even bones. Maybe those losses were adaptations to a life spent infiltrating carcasses in the dark, deep ocean, much like their flaccid, nutrient-absorbing skins are. “Hagfishes might look primitive; they’re actually very specialized,” Miyashita adds.

Their signature slime might have also evolved as a result of that lifestyle, as a way of fending off predators that were competing for cadavers. “Everything about hagfish is weird,” says Fudge, “but it all kind of fits.”

Ed Yong is a former staff writer at The Atlantic. He won the Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting for his coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic.