IN GRADE 1O OUR SOCIAL STUDIES CLASS WENT ON A WEEKEND TRIP TO THIS SITE TO DO ARCHAEOLOGICAL WORK WITH U OF A STUDENTS THE SPIRIT WARRIORS STILL ARE THERE AS I FOUND OUT BY WANDERING THE CIRCLES UNDER THE STARS, DOING MY SPIRIT JOURNEY IN ANCIENT SACRED SPACE

I DID NOT KNOW IT WAS THIS ANCIENT THOUGH BUT IT SURE FELT LIKE IT

Anishinabek Rise

We have been here since the beginning of time...We have always been here....

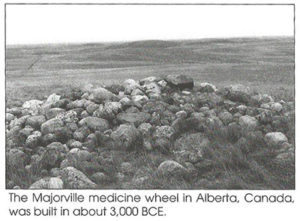

"The ancient medicine wheel — more accurately, it’s a geoglyph, which is essentially a man-made design made on the ground with stones or earth — was constructed over the span of a few thousand years. Incredibly, its first stones were placed approximately 5,000 years ago. So, to put this into context, the wheel is 1,000 years older than Stonehenge, 3,500 years older than the Mayan Pyramid of Chichen Itza, 500 years older than the Great Pyramid of Giza. Now, perhaps, you have a clearer picture of what we’re dealing with here. In Alberta. Just a couple of hours from Calgary."

The Majorville Medicine Wheel, a sacred First Nations site that has been left largely intact in Alberta, is one of the oldest man-made structures you can visit in Canada

Ride with us as we explore two ancient medicine wheels, one of which is one of the oldest spiritual/religious monuments in the world.

More information about the Majorville Cairn And Medicine Wheel: https://goo.gl/cxoqUJ

More information about the Sundial Hill Medicine Wheel: https://goo.gl/bjNawC

Searching for Ancient Medicine Wheels https://youtu.be/dSO980LUBqc

Anishinabek Rise

We have been here since the beginning of time...We have always been here....

"The ancient medicine wheel — more accurately, it’s a geoglyph, which is essentially a man-made design made on the ground with stones or earth — was constructed over the span of a few thousand years. Incredibly, its first stones were placed approximately 5,000 years ago. So, to put this into context, the wheel is 1,000 years older than Stonehenge, 3,500 years older than the Mayan Pyramid of Chichen Itza, 500 years older than the Great Pyramid of Giza. Now, perhaps, you have a clearer picture of what we’re dealing with here. In Alberta. Just a couple of hours from Calgary."

The Majorville Medicine Wheel, a sacred First Nations site that has been left largely intact in Alberta, is one of the oldest man-made structures you can visit in Canada

Ride with us as we explore two ancient medicine wheels, one of which is one of the oldest spiritual/religious monuments in the world.

More information about the Majorville Cairn And Medicine Wheel: https://goo.gl/cxoqUJ

More information about the Sundial Hill Medicine Wheel: https://goo.gl/bjNawC

Searching for Ancient Medicine Wheels https://youtu.be/dSO980LUBqc

Aug 4, 2015 - The August long weekend has come and gone, and with it, the 2015 Forgotten Alberta Road Trip . Following much debate over appropriate ...

Jan 29, 2009 - On a warm late-August day in 1980, that list drew him to what he has come to call Canada's Stonehenge, which is also the title of his book.

Canada's Stonehenge, a Vulcan County treasure. Neel Roberts More from Neel Roberts. Published on: July 7, 2016 | Last Updated: July 7, 2016 9:31 AM EDT.

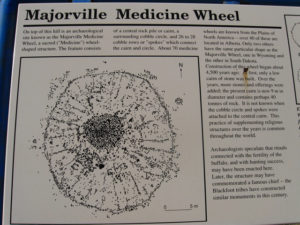

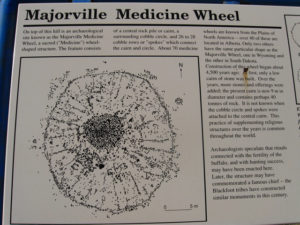

Description: Majorville Cairn and Medicine Wheel, near Bassano

Caption: View from central cairn

Copyright/Credit: Alberta Culture and Communiy Spirit, HIstoric Resources Management

Type: Image

The centre cairn at the Majorville Medicine Wheel. Courtesy, Andrew Penner

As the ragged ribbon of road — no, jeep-trail is more accurate — meandered through the god-knows-where prairie, a timeless aura soon took hold. No pioneering boy had ever plowed these plains. I could be on Mars, I thought. And about the only thing that told me I wasn’t was the odd sign or marker. One indicated that an old schoolhouse had once existed on that spot a hundred years ago. And a couple of others indicated, thankfully, that I was on the right “road” to the ancient medicine wheel.

So, cosy in my beat-up 4×4, Corb Lund croaking on the stereo, I went deeper into the unknown. And, after 20 minutes, give or take, of bumping along I finally reached the site: “Canada’s Stonehenge.” I parked the truck, gathered some photography gear, hopped outside (no point locking it, there was no other soul within 20 kilometres) and scampered to the top of the hill to the ancient cairn of rock.

When I reached the lichen-coated stones I looked all around, got my bearings, and felt the warm Chinook wind sweeping over everything. I was on the highest point for, perhaps, 100 kilometres in any direction. The power of this place, this pre-historic “wheel,” was sneaking up on me. To the west, thin, wind-blasted shortgrass, as far as the eye could see, morphed into sky. To the east, the deep, water-carved banks of the Bow sliced through the golden plains. They definitely picked a nice spot, I thought.

“They” being the ancient ancestors of the Blackfoot, the real pioneers of the plains. And, interestingly, the Majorville Medicine Wheel, one of a number of sacred First Nations sites that have been left largely intact in southern Alberta (yes, it does take some work to get there!), is one of the oldest man-made structures you can visit in Canada.

The Majorville Medicine Wheel from a high elevation. Courtesy, Andrew Penner

The ancient medicine wheel — more accurately, it’s a geoglyph, which is essentially a man-made design made on the ground with stones or earth — was constructed over the span of a few thousand years. Incredibly, its first stones were placed approximately 5,000 years ago. So, to put this into context, the wheel is 1,000 years older than Stonehenge, 3,500 years older than the Mayan Pyramid of Chichen Itza, 500 years older than the Great Pyramid of Giza. Now, perhaps, you have a clearer picture of what we’re dealing with here. In Alberta. Just a couple of hours from Calgary.

In his book, Canada’s Stonehenge, author and professor emeritus at the University of Alberta Gordon R. Freeman describes the Majorville Medicine Wheel as “the most intricate stone ring that remains on the North American Plains.” And Freeman should know. He spent the better part of 30 years studying geoglyphs around the world and, specifically, the Majorville wheel (which he prefers to call a stone ring or circle, words that better resonate with First Nations culture). The circle — as evidenced by teepees, drum circles, healing circles, stone effigies, and so on — is a sacred form for First Nations people.

Although the Majorville Medicine Wheel (the town of Majorville is now gone, the closest town is Lomond, located approximately 30 km south of the wheel) is not as visually impressive as monuments such as Stonehenge, the significance of the site is just as profound. Interestingly, Freeman, who camped at this site for weeks on end in the ’80s and ’90s, discovered remarkable similarities to Stonehenge and other ancient sun temples. The alignment of rocks, surrounding stone markers, and spokes (although barely recognizable, there are 28 spokes, or “rays,” that fan out from the centre cairn) all point to a solar calendar that would most likely have been used for ceremonial purposes.

A sign at the Majorville Medicine Wheel. Courtesy, Andrew Penner

However, pinning down all the mysteries and specific purposes of the site is difficult, if not impossible. Through the ages, different tribes and people could have used it for many different reasons, including as a site for prayer, sun dances, and as a death lodge. It could also have been used as a navigational aid, boundary marker, and an astronomical observatory. And, given the many simple offerings I noticed on the rock cairn during my visit, it’s still used regularly as a place of worship and prayer by the Blackfoot and others who believe in its spiritual power. (Obviously, any historical or spiritual site should be respected and honoured. Any tampering or removal of objects, old or new, is a crime.)

But, as notable as the Majorville wheel is, it’s actually one of many wheels in Alberta and Saskatchewan. While numerous ancient wheels were plowed under and destroyed during settlement, over 70 are still intact on the Canadian Prairie. Many are on private land and require special permission to visit. And some, no doubt, have yet to be discovered.

Interestingly, 14 wheels alone have been documented and visited by archaeologists at CFB Suffield, which is the largest military training base in Canada and home to 2,700 square km of remote, never-plowed prairie. Besides the medicine wheels, over 2,000 additional sites on the massive base have been documented as locations that contain teepee rings, cairns, stone figures, and so on. Unfortunately, these are all off-limits to the public.

Blackfoot Crossing Historical Park near Cluny, Alta. Courtesy, Andrew Penner

In her excellent book, Stone by Stone: Exploring Ancient Sites on the Canadian Plains, author Liz Bryan chronicles dozens of sites, including medicine wheels, buffalo jumps, rock art, effigies, teepee rings, and more. In addition to Majorville, Bryan cites Sundial Medicine Wheel (near Carmangay) and the Rumsey Medicine Wheel as the most easily visited.

On my way back to Calgary after visiting the Majorville Medicine Wheel, I stopped at the Blackfoot Crossing Historical Park to, hopefully, gain a little more clarity on medicine wheels and the incredible history of the Blackfoot people. Not surprisingly, given the country-altering history at Blackfoot Crossing (this is where Treaty 7 was signed), I actually left with more questions than answers.

And, to top it off, my tour guide mentioned that they just recently, thanks to a significant grass fire, discovered a giant new medicine wheel somewhere deep in Siksika territory. Long story short, I’ve got my fingers crossed that another medicine wheel road trip is in my near future.

Gordon Freeman Tells Us About Canada’s Stonehenge – Slideshow

Canada’s Stonehenge Astounding Archaeological Discoveries in Canada, England, and Wales

Here are the first 40 pages of the book to look at as a slideshare.

|

| ||

Stonehenge and Majorville Sun Temples

The first Centre for Interdisciplinary Science in Alberta was the Radiation Research Centre, which I designed in 1964 by broadening the concept of an Institute in Manchester, England. It was built in 1964/5 and I Directed it until retirement in1995. Research included Radiation Chemistry and Physics, Electronics, Astrophysics, Radiation Zoology, Botany and Genetics, and a little Medicine and Food Science. Studies broadened to generalized nonlinear dynamics and changes in complex systems. The overall field is called Kinetics of Nonhomogeneous Processes (KNP). Three books were published:

· Kinetics of Nonhomogeneous Processes: A practical introduction for Chemists, Biologists, Physicists, and Materials Scientists, ed. Gordon R. Freeman, Wiley-Interscience, New York, 1987.

· Proceedings of the International Conference on Kinetics of Nonhomogeneous Processes, ed. Gordon R. Freeman, Canadian Journal of Physics, Sept. 1990 issue, volume 68, pages 655-1111.

· Canada's Stonehenge: Astounding Archaeological Discoveries in Canada, England, and Wales, Kingsley Publishing, 293 +xviii, 2009.

Pattern recognition is a powerful tool that assists understanding of similar behavior in seemingly unrelated systems. Similar patterns are generated by analogous mechanisms.

Interdisciplinary studies are a prominent way of the future in the Physical, Life and Social Sciences, and in the Arts.

Publications:

G.R. Freeman, "Hidden Stonehenge", 2nd edition, Watkins Publishing, England, March 2012. www.dbponline.co.uk; http://www.watkinspublishing.co.uk

G.R. Freeman, "Global warming", American Physical Society, Forum on Physics and Society, 2006, 35 (No. 2), 4-5.

G.R. Freeman, "The Art of Science", Fifty3, 2006, 7 (No. 2), pages 7, 22, 23.

G.R. Freeman, "Teaching Quantum Mechanics", University Affairs, 2005, June, page 5.

G.R. Freeman, P.J. Freeman, 2001. "Observational Archaeoastronomy at Stonehenge: Winter Solstice Sun Rise and Set Lines Accurate to 0.2° in 4000 BP", 33rd Annual Meeting, Canadian Archaeological Association, Ottawa 2000. Proceedings; Eds. J.-L. Pilon, M. Kirby, C. Thériault. Ontario Archaeological Soc. and Canadian Archaeological Assoc., pp 200-219. National Library of Canada site. http://collection.nlc-bnc.ca/100/200/300/ont_archaeol_soc/annual_meeting_caa/33rd/ottawa2000proceedings.htm

G.R. Freeman, P.J. Freeman, 2001. "Observational Archaeoastronomy at the Majorville Medicine Wheel Complex: Winter and Summer Solstice Sun Rise and Set Alignments Accurate to 0.2°", 33rd Annual Meeting, Canadian Archaeological Association, Ottawa 2000. Proceedings; Eds. J.-L. Pilon, M. Kirby, C. Thériault. Ontario Archaeological Soc. and Canadian Archaeological Assoc., pp 220-229. National Library of Canada site. http://collection.nlc-bnc.ca/100/200/300/ont_archaeol_soc/annual_meeting_caa/33rd/ottawa2000proceedings.htm

G.R. Freeman, "Sacred Rocks of Alberta: Description of Eleven Glyphed Boulders, a Meteorite, and Their Sites," University of Alberta Archives, Edmonton, Accession No. 2000-44. 126 pp. manuscript including index, 531 annotated photos, 3 sketches, 14 site maps, about 1368 photo negatives and prints.

G.R. Freeman, N.H. March, "How Might Chemical Reaction Rates in Solution be Affected by Intense Density Fluctuations of the Solvent?", Physics and Chemistry of Liquids 1999, 37, 627-631.

G.R. Freeman, N.H. March, "Triboelectricity and Some Associated Phenomena", Mater. Sci. Tech. 1999, 15, 1454-1458.

G.R. Freeman, L.D. Coulson, N.H. March, "On the Ehrenberg-Siday- Aharonov-Bohm (ESAB) and Aharonov-Casher (AC) Effects", Mod. Phys. Lett. B 1998, 12, 933-942.

This is a rough road that you share with cows, and it’s important to go very slowly. After about 15 km there is a Y in the road, where you must bear to the left. There is a cattle guard (Texas gate) and the medicine wheel hill is about 3 km farther. There is a sign at the bottom of the fenced hill so you know you have arrived. It was extremely windy that day; although it was far too hot to wear my coat, I had to use its detachable hood for ear protection from the 60 km/h gusts. Fortunately there were only cows to witness this fashion faux pas.

This is a rough road that you share with cows, and it’s important to go very slowly. After about 15 km there is a Y in the road, where you must bear to the left. There is a cattle guard (Texas gate) and the medicine wheel hill is about 3 km farther. There is a sign at the bottom of the fenced hill so you know you have arrived. It was extremely windy that day; although it was far too hot to wear my coat, I had to use its detachable hood for ear protection from the 60 km/h gusts. Fortunately there were only cows to witness this fashion faux pas.

Although I now live on the West coast (and consider it home), there is a real danger when I get back onto prairie soil. Not only did I grow up in Alberta, but it is also the place of my ancestry for many generations. So when my feet get on prairie grass, they start trying to grow roots and stay. It is like feeling you can stretch your arms and encompass the earth, even though the sky is so wide it seems endless.

Although I now live on the West coast (and consider it home), there is a real danger when I get back onto prairie soil. Not only did I grow up in Alberta, but it is also the place of my ancestry for many generations. So when my feet get on prairie grass, they start trying to grow roots and stay. It is like feeling you can stretch your arms and encompass the earth, even though the sky is so wide it seems endless.

Majorville Medicine Wheel

70 First Nations medicine wheels are known to exist on the plains of North America, and more than half of them are in Alberta, Canada

By Mary Johnson

It sounded simple: just turn south onto Secondary Road #847 at Bassano and drive toward the Bow River for 15 kilometers. We honestly didn’t think the Majorville Medicine Wheel would be that hard to find, even without explicit directions. For one thing, it was almost certainly on the highest hill around. Also, since it was the second best example of an ancient medicine wheel in North America, surely the locals would be able to point us in the right direction. It sounded like just the perfect way to spend a summer afternoon in Alberta, Canada. Most important, it sounded like a power place. In her book Western Journeys: Discovering the Secrets of the Land , Beverly Sinclair described her experience approaching a medicine wheel: “…as though the ghosts of buffalo hunters are watching me.” She said she felt “strangely moved by the hilltop’s mystery.”

, Beverly Sinclair described her experience approaching a medicine wheel: “…as though the ghosts of buffalo hunters are watching me.” She said she felt “strangely moved by the hilltop’s mystery.”

After several hot, dusty and totally confused hours of hiking across prairie, surprising cows and alarming gophers, we had to give up and go home. The first lesson in looking for archaeological sites seems to be to get directions from someone who knows what they are talking about!

Original purpose now lost

I didn’t know much about medicine wheels when I started and even less after doing some research. Do medicine wheels in today’s culture now embody something totally different from the original concept? Since the coming of Europeans to North America, the exact knowledge and purpose of medicine wheels has been lost. The term has come to mean many things to many people, and has taken on New Age concepts like astrology, earth and environmental beliefs, dream work, and spiritual awakening. Now it is embedded in pop culture the say way that “sit-ins” used to be part of the ‘60s. In some national parks, the rangers spend a lot of their time dismantling hikers’ medicine wheels and returning the land to its natural state. Native Americans (like the popular author Sun Bear) have rooted a whole system of belief and behavior in the medicine wheel.

The ancient medicine wheel does not have any “right” construction, but archaeologists have classified roughly eight types and consider it necessary to have at least two of the following three traits: a central stone cairn, one or more concentric stone circles, and two or more stone lines radiating outward from a central point. Some of the sites may have been burial mounds of a revered chief or warrior. Blood Indians of southern Alberta have build modern wheels to commemorate ancestors; a long-standing tradition for possibly thousands of years.

Ancient astronomical uses?

It I widely believed that one function of medicine wheels was astronomical. Medicine wheels are always located on the top of the highest hill in a given area and have a clear view of all four directions. One astronomer we spoke to (David Vogt of Vancouver) examined the hypothesis in the past and says that although there is some stone evidence of astronomical alignment, it cannot be proven in fact. After studying the Majorville and Big Horn wheels, he says they are still completely mysterious and could have had many purposes; from vision quests and sundances to alien landing sites.

One of the more likely scenarios is that medicine wheels were an important part of Native American ritual. One of the rocks frequently found at medicine wheels were called “iniskim” by the Siksika (previously known as Blackfoot) and were “buffalo calling rocks.” These were powerful totems. Buffalo provided everything these people needed to survive the frequently harsh environment of the plains. Both Piegan and Siksika legends tell of the first iniskim being discovered by a woman when it “sang” to her of its magical powers. It is certain that these were important in hunting and buffalo fertility rituals.

Still used by first nations

We spoke to Floria Duck Chief in the Siksika cultural office, who had gone to the Majorville wheel with two tribal elders. At the base of the hill, they prayed to the four directions and left tobacco in four directions before they climbed up to the wheel. Once at the top, they prayed again before going into the circle, approaching it from the north and coming into the circle facing the south. Floria also remembered that, when she was very young, her grandmother showed her an iniskim rock she kept in a pouch, saying it protected her. It had been painted – rubbed with red ochre.

Weeks after my first attempt to find the Majorville wheel, I got lucky and found a retired archaeologist (Barney Reeves) who has been roaming the Alberta prairies for 40 years, and who, coincidentally, happened to know my father from their university says. Barney told us the “legal” description of the site along with some very helpful directions. Armed with a topographical map showing townships and ranges, we again set off. With only a few wrong turns, we finally arrived at the bottom of the Majorville Medicine Wheel hill.

Majorville Medicine Wheel

This time, although we drove straight there from Calgary, it took us a good two hours. Four-wheel drive would have been helpful but not absolutely necessary. We took Highway #1 (the Trans Canada) going east from Calgary, and then turned sough on Highway #24 at Vulcan (a tiny farming community which has a model of the Starship Enterprise at the town centre). Then we took #534 east to Lomond, where we turned north on /secondary Road 845. Then we turned east onto Secondary Road 539 and drove for about 16 km. We then turned north onto a rough section of road (exactly 5 km from the Badger Lake turnoff) and followed that for about 18 km.

This is a rough road that you share with cows, and it’s important to go very slowly. After about 15 km there is a Y in the road, where you must bear to the left. There is a cattle guard (Texas gate) and the medicine wheel hill is about 3 km farther. There is a sign at the bottom of the fenced hill so you know you have arrived. It was extremely windy that day; although it was far too hot to wear my coat, I had to use its detachable hood for ear protection from the 60 km/h gusts. Fortunately there were only cows to witness this fashion faux pas.

This is a rough road that you share with cows, and it’s important to go very slowly. After about 15 km there is a Y in the road, where you must bear to the left. There is a cattle guard (Texas gate) and the medicine wheel hill is about 3 km farther. There is a sign at the bottom of the fenced hill so you know you have arrived. It was extremely windy that day; although it was far too hot to wear my coat, I had to use its detachable hood for ear protection from the 60 km/h gusts. Fortunately there were only cows to witness this fashion faux pas.

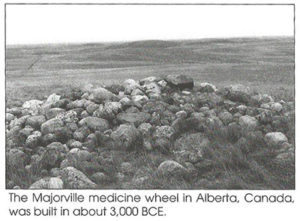

As I approached the wheel, I was surprised at the size of it. It has a central cairn about nine meters across, surrounded by a stone circle. About 28 spokes link the central cairn and circle. All in all it was about 30 meters across. The thing that made me catch my breath, however, was not the construction or the stones, but what was left among the stones.

There were offerings of braided rope (it looked like cedar bark), ears of corn and feathers tied to rocks and sticks with red material. It looked as though it might have done a thousand years ago when the Caucasian invasion was yet undreamed of. I looked around me and saw prairie as far as the eye count see. The Bow River gorge was less than a kilometre away. I felt sincere awe and an appreciation of the lives of the people who build the wheel.

As old as Stonehenge

The wheel had been partly excavated (and then restored) by archaeologists in 1971. Artefacts were found that dated the wheel to 3,000 BCE. This is only 500 years after construction was started on Stonehenge, at that point in human history, time spans of 500 years are really no time at all. Were these “simultaneous inventions” just coincidental, or did some yet-undiscovered force influence them both?

The really interesting thing to me was that there appears to be a period of time, between 2,000 and 3,000 years ago, when the wheel was not in use. What happened? Was there a plague, a revolution, a crisis? More importantly, what motivated its re-use? Was the knowledge of the wheel’s existence and purpose forgotten and rediscovered, or was it held and passed on through the millennia?

The wild Alberta prairies

Although I now live on the West coast (and consider it home), there is a real danger when I get back onto prairie soil. Not only did I grow up in Alberta, but it is also the place of my ancestry for many generations. So when my feet get on prairie grass, they start trying to grow roots and stay. It is like feeling you can stretch your arms and encompass the earth, even though the sky is so wide it seems endless.

Although I now live on the West coast (and consider it home), there is a real danger when I get back onto prairie soil. Not only did I grow up in Alberta, but it is also the place of my ancestry for many generations. So when my feet get on prairie grass, they start trying to grow roots and stay. It is like feeling you can stretch your arms and encompass the earth, even though the sky is so wide it seems endless.

On a beautiful day on the prairie it is impossible to realize that this can be some of the most inhospitable land on the planet for humans to dwell. In the winter, the wind screams across the hills, freezing everything in its path, and the temperature will be –40 for weeks on end. I found it hard to imagine anyone being on the top of this hill in the dead of winter. I’m sure gatherings were probably regular and seasonal, but probably not in the colder months.

The site is vulnerable

I have a real sense of trepidation in telling other people about the wheel. It is a place that has a huge sense of ritual and being, but there aren’t busloads of tourists driving by. In fact, to get to the wheel you have to be quite determined and armed with maps. A sense of adventure wouldn’t go amiss. The site is unguarded and vulnerable to vandalism and souvenir hunters. My fear stems from what happened to the Big Horn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming. Since its discovery in the late l800s, it has been plundered and radically altered from its original state’ so much so that a number of groups including the Medicine Wheel Alliance, the Big Horn National Forest, and the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office signed an agreement in 1933 limiting access. It’s not surprising those steps took place considering that each year over 70,000 people visit between July and November.

Bad karma from stealing stones

To anyone contemplating taking home a “souvenir” from a medicine wheel, I offer a warning: one couple from Philadelphia who visited the Big Horn wheel stole one of its rocks. A series of such bad experiences befell them that they had to mail the rock back. This is not an isolated incident. In the book In the Ring of Fire (Mercury House, 1997) James Houston reports that an average of ten people per week mail rocks back that they had stolen from Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. It is taboo to remove even a tiny stone from the home of Pele, the goddess of fire. Letters accompanying the returned rocks contain long lists of misfortunes that haunted tourists who ignored the warnings. The law of karma is indeed real. What goes around comes around. It’s that circle thing.

(Mercury House, 1997) James Houston reports that an average of ten people per week mail rocks back that they had stolen from Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. It is taboo to remove even a tiny stone from the home of Pele, the goddess of fire. Letters accompanying the returned rocks contain long lists of misfortunes that haunted tourists who ignored the warnings. The law of karma is indeed real. What goes around comes around. It’s that circle thing.

Please do not leave offerings

One final thought about leaving offerings at sacred places. It has become a very serious problem, especially in England, where a group Save Our Sacred Sites, has been formed to protect ancient monuments. They advise it is not necessary to show your respect for a site by lighting candles or incense, leaving flowers, grain, salt or anything.

Adding crystals to “re-harmonize” ancient stones is not only arrogant but potentially harmful to the energies at a site. So, even if First Nations people leave sweetgrass, tobacco or feathers at a medicine wheel, that doesn’t mean you should. You can show your respect through your attitude and your behavior. You can clean up litter left by less respectful visitors. You can also talk to others about the need to preserve and protect ancient sacred sites.

The Boscawen’un stones in Cornwall have recently been seriously damaged and may soon be fenced off and as inaccessible as Stonehenge has become. We are fortunate that the Majorville Medicine Wheel is now freely accessible to us all. Let’s hope it can stay both safe and free for future generations to experience its power and ponder its mysteries.

This article was first published in the December/January 1998 issue of Power Trips magazine.

This article was first published in the December/January 1998 issue of Power Trips magazine.